|

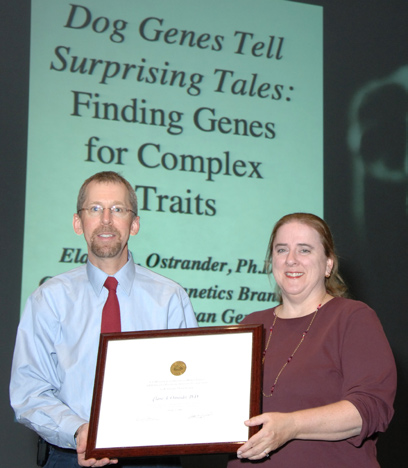

| Dr. Elaine Ostrander and NHGRI scientific director Dr. Eric Green |

Those attending the 2008 G. Burroughs Mider Lecture in Masur Auditorium gained a greater appreciation of canine genomic research and the complex traits of dogs, whether attentive companions, specialized workers or show contenders.

Leading canine geneticist Dr. Elaine Ostrander, chief of NHGRI’s Cancer Genetics Branch, presented the lecture, named for the first director of NIH laboratories and clinics. The honor of delivering the lecture is extended

each year to an NIH intramural scientist for his or her outstanding contributions to biomedical

research.

Ostrander’s studies capitalize on several hundred years of closed breeding that has produced a fantastic

variety in the size and shape of more than 400 dog breeds recognized worldwide. Her work draws mostly on the 150 or more breeds recognized

by the American Kennel Club. Ostrander’s

talk described several genomic and genetic research projects that are exploring this remarkable

morphologic and behavioral diversity.

One breed in particular—the Portuguese water dog—has helped Ostrander and her colleagues discover a gene variant related to stature in dogs, precisely because a broader-than-usual range of size variations is allowed in this breed. Some particularly small dogs, like Chihuahua and Pekingese breeds, have the same gene variant

as those of small Portuguese water dogs.

Another breed sometimes bred for racing—the whippet—was used to identify another gene variant that gives a speed advantage when present in one but not two copies. Ostrander also said that the coats of dogs present many other traits for discovery, including determination

of texture or growth patterns that give some animals unique features that breeders call furnishings.

“This multi-breed approach is a very powerful way of doing complex genetics,” Ostrander said. “Each one of the 150 or so breeds offers unique opportunities for thinking about genes that are responsible for phenotypes that are of interest to ourselves.”

Work in her laboratory also explores cancer susceptibility in canines and humans—including squamous cell carcinoma, bladder cancer and a soft tissue cancer called malignant histiocytosis—because many canine cancers closely parallel

those in humans.

Ostrander explained that any fixed, breed-defining canine trait can be mapped. She and collaborators are engaged in a canine-mapping initiative called CANMAP,

which involves the genetic analysis of 1,000 dogs from 85 different breeds. The CANMAP dataset will ultimately be publicly available, giving any researcher

the opportunity to access the data, Ostrander said. Her laboratory will use this data to perform genome-wide association studies to identify regions of the canine genome statistically linked to traits of interest.

A remarkable component of Ostrander’s laboratory effort is the collection of blood and saliva samples at events such as dog shows and obedience and herding trials. The research is accomplished without the need to breed or house dogs, as the group has built important collaborations with dog owners and organizations.

The annual Mider lecture is part of the NIH Director’s Wednesday Afternoon Lecture Series. Archives of this talk and others in the series can be viewed online at the NIH Videocasting and Podcasting portal of the Center for Information

Technology.