|

|

|

|

Angela Atwood-Moore, Biologist, Research Associate, Laboratory of Gene Regulation and Development, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health

|

BiologistMeet a real Biologist, Angela Atwood-Moore

1. I chose this career because...

2. My typical workday involves...

3. What I like best/least about my work...

4. My career goals...

5. When I'm not working, I like to...

6. A career in biology without a Ph.D....

|

|

1. I chose this career because...

|

Back to Top

|

|

|

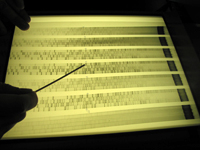

Angela reviews DNA sequencing read-outs to look for mutations in transposons.

|

I chose to become a biologist because I had a great 8th grade biology teacher. He made the subject exciting and applicable to life. Ever since I had his class, I knew I wanted to do research in biology. There are no scientists in my family. My parents are both teachers.

When I needed to pick a college, I looked for a great undergraduate biology program. I grew up I in Utah, but I would have gone anywhere in the country for a good program. Reed College was a small school in Oregon with a unique biology program. While there, I got to design my own project, do independent research with hands-on work in the lab, and complete a thesis for graduation.

College Education

|

|

2. My typical workday involves...

|

Back to Top

|

|

|

On an autoradiograph (image on a film), Angela points to yeast samples that are plus and minus for transposition.

|

My typical workday revolves around a big research project that I have worked on for the past thirteen years. The project focuses on segments of DNA (http://www2.merriam-webster.com/cgi-bin/mwmednlm?book=Medical&va=DNA) know as transposons. They are sometimes referred to as “jumping genes” because they can make copies of themselves and can insert themselves into the genome (http://www2.merriam-webster.com/cgi-bin/mwmednlm) of a single cell. You can think of them as tiny organisms because they have their own genes (http://www2.merriam-webster.com/cgi-bin/mwmednlm). Because of their jumping characteristics, some scientists believe that transposons may be precursors to viruses. However, transposons are not infectious. In some organisms, more than 50% of their genome is made-up of transposons.

In our lab, we study transponsons in yeast. Yeast cells are perfect for the study because they are the simplest equivalent to a human cell. Less than 20 years ago, my boss identified transposons in a certain type of yeast. He saw that they were active, could copy themselves, and move around in the genome. At that time, these regions were considered “junk DNA,” because the prevalent thought among scientists was that they had no function. Now we are learning that these regions do have functions.

Jumping Genes May Help Us Fight AIDS

Research in our lab (http://eclipse.nichd.nih.gov/nichd/lgrd/sete/index.htm) is showing that some transposons behave like the virus known as the Human Immunodeficiency Virus or HIV that causes Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome or AIDS - both can insert themselves into or near a gene and affect its function. This insertion ability is one of the reasons that the AIDS virus is highly infectious. The similarities make the transposons a good and safe model to study HIV.

In one of my earlier projects, I created mutations (http://www2.merriam-webster.com/cgi-bin/mwmednlm) in the yeast transposons and looked for ones that could no longer jump. We screened nearly 6000 mutants and more than half were defective in transposition. After many more screenings, we narrowed the 3000 down to 10 mutants that looked most promising for continued study. The final results were exciting. We identified a new role for a protein that is important in the life cycle of the transposon. We identified specific regions of this protein as a new potential target for other researchers who are developing drugs against HIV.

For the Mutation Project, My Laboratory Tasks Included:

- Using a cocktail of chemicals to create mutations in transposons. In experiments, the transposons are carried inside plasmids (small circular segments of DNA that can divide independently from the cell’s normal DNA.)

- Transforming (or re-inserting) the plasmids (carrying the mutated transposon) into the yeast cells

- Screening the cells to look for transposons that have lost their ability to jump around the genome. These mutants can give other researchers clues for developing effective drugs against HIV.

- Isolating and sequencing the DNA of the transposon (in the region where the mutations were randomly introduced)

Managing the Laboratory

As the lab manager, I must handle many administrative duties. These tasks include general lab maintenance such as ordering equipment and supplies and organizing the space. I also help with the paperwork involved when we have a new person employed in the lab. I teach them the laboratory techniques needed to carryout their individual experiments.

|

|

3. What I like best/least about my work...

|

Back to Top

|

|

|

Angela sits at the computer to order supplies, correspond with fellow bike commuters, read science journals, and write-up her own research results.

|

What I like best about my work is being able to do research here at the NIH. Sometimes I can’t believe I get paid to do this work. You can have a great scientific question, and then get

plenty of time and resources to answer the question. Science is so open. There is no shortage of things to study. You just have to decide where it is best to apply your time and resources. Scientists here are very approachable. They understand the process of scientific inquiry.

What I like least about my work is that it takes a lot of time. This is not an ordinary 9 to 5 job. The work schedule can change depending on the project you are working on. It is very unpredictable.

I have cancelled a lot of outside activities to continue my experiments. It is not something I resent though. I enjoy the work, and look forward to getting meaningful results.

|

|

4. My career goals...

|

Back to Top

|

|

|

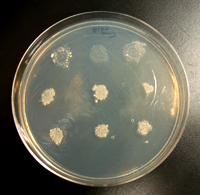

Under the right media conditions, transformed yeast cells will grow (bottom two rows), or not grow (top row) depending on the DNA sequences present in the sample.

|

My career goals are to find a way to teach because I enjoy sharing my enthusiasm of science with students. I volunteer for our institute’s mentoring program. It pairs NIH scientists with students at a local elementary school. Two or three times a year I go into the classroom and teach the students an experiment. I include a lot of hands-on activities so the students may have fun and understand the scientific process. I contact the teachers to find out what the students are studying and then design activities to complement what they are learning. At the moment, the mentoring program has stalled due to the increasing time demands of the teachers in the classroom.

|

|

5. When I'm not working, I like to...

|

Back to Top

|

|

|

Angela shows a new colleague how to load and run an agarose gel.

|

When I’m not working, I like to bike or do any kind of outdoor activity. Currently, I volunteer as the President of the NIH Bicycle Commuter Club (http://www.recgov.org/r&w/nihbike/). It is a community of NIH employees that frequently bike to work. We organize and facilitate the annual “Bike to Work Day” events. In the summer months, we provide regular trail maintenance services.

I am also a part-time fitness trainer at the NIH Fitness Center and a local YMCA. I teach three to four classes per week. When I’m not volunteering, I enjoy spending time with my husband and dog.

|

|

6. A career in biology without a Ph.D....

|

Back to Top

|

|

|

| |

Angela parks her bike in front of her building on the NIH campus and sports an NIH Bicycle Commuter Club jersey.

|

I think it is important for people to know that you can have a career in biology without obtaining a Ph.D. To gain independence in research, you typically need to have an advanced degree.

But this has not been the case for me. I have a great supervisor who believed in me from the start of my career, and gave me opportunities to learn and grow in my job. I have independent research projects, and have written and published scientific research articles for major peer-reviewed journals.

|

|

|

|

|