|

Breast Density in Mammography and Cancer Risk

Studies from the last 3 decades have shown that breast density is directly linked to breast cancer risk. The magnitude of that risk is still under some debate, says Dr. Stephen Taplin, a senior scientist in NCI's Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences who leads research on breast cancer screening as the project director for the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC). But, he continues, "it is widely held to be one of the biggest risk factors, though the question of why it carries such a high risk is still not answered."

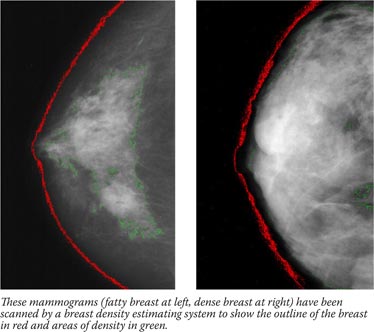

Breast density is not an intuitive concept, and has little to do with breast size. Breast density actually refers to the amount of white area on a breast that otherwise appears black on a mammogram. The balance of white and black reflects the breast composition and relative amount of glandular tissue, connective tissue, and fat. Different methods of estimating the proportion of white area on the mammogram exist and vary from the perception of the radiologist to using a software program to outline the white area and compare it to the total breast area.

Though it can be influenced by lifestyle factors, twin studies show that the underlying causes of breast density are mostly inherited. Higher breast density is more common in some ethnic groups, including White women. It is also more common in younger women, beginning when hormones kick in during puberty and continuing through the childbearing years.

Breast density decreases during menopause in a process called breast involution, where the milk-glands and ducts atrophy and connective tissue disappears. But in some women, these tissues persist into older age, and these are the women for whom the risk is a real concern, says Dr. Karla Kerlikowske, a professor of medicine and epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and principal investigator for the San Francisco BCSC research site.

"A 30-year-old woman can have dense breasts, but her underlying risk is still likely very low without other known risk factors," she explains. "We're really concerned with women who are in their 50s and 60s, who have persistent breast density, and who may benefit from a different screening procedure or some other preventive measure, such as chemoprevention."

To identify such women, Dr. Kerlikowske and colleagues in the BCSC published breast cancer risk prediction models in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute and the Annals of Internal Medicine. These models used the most common measurement for breast density, BI-RADS, to project cancer risk out to 1 and 5 years respectively for Caucasian, Asian, Hispanic, and Black women between the ages of 40 and 74, taking into account family history and breast biopsies.

The second model correctly identified women as low-risk and high-risk slightly better than the Gail model, but in the middle-risk group it was similar to the Gail model. The model hasn't been developed for clinical use, according to their paper.

The BI-RADS measuring system involves a radiologist scoring a mammogram in one of four categories according to the extent of contrast within the outline of the breast: x-rays pass easily through fatty tissue, which shows up as darker areas on the image, but are blocked - and thus appear white - by milk ducts, lobes, and the web of connective tissue that tethers everything together. Studies have shown that women who have extremely dense breasts have a three- to fivefold increased risk of breast cancer compared with women who have mostly fatty breasts.

One concern has been whether the breast cancer associated with dense breasts is due to a "masking effect," where the lack of contrast (that is, a breast image that is very white throughout) between normal tissue and tumors in dense breasts makes it difficult to discriminate between the two.

However, this isn't the only explanation for the relationship. "If we look at the risk association over time," says Dr. Taplin, "the longer out we go, the more evident it is that there's a fundamental risk factor that isn't about masking. It's something about the tissue itself."

|

|

Additional Imaging Technologies

Research on screening technologies, including digital mammograms, ultrasound, computer-assisted mammograms, and magnetic-resonance imaging, may also help address the dense-breast dilemma. However, these technologies are still being evaluated and the equipment in some cases is not yet widely available in clinics.

|

|

|

|

What that could be isn't yet clear. In NCI's Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics (DCEG), Drs. Mark Sherman, Louise Brinton, and Gretchen Gierach are looking for answers through the Breast Radiology Evaluation and Study of Tissues (BREAST) Stamp project, on which Dr. Taplin is also a collaborator. To date they have enrolled 179 women through the BCSC and will be examining tissues from breast biopsies and surgical resections to find markers that are associated with breast density and may determine whether epithelial cells develop into cancer precursors and cancer.

"Our working hypothesis is that the elevated risk associated with mammographic density reflects an altered microenvironment," explains Dr. Gierach, noting that they are looking closely at hormone levels and markers of inflammation. Another DCEG project led by Drs. Mark H. Greene and Jennifer Loud, the Breast Imaging Study, is examining how BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations relate to breast density and includes a pilot analysis of the relationship between mammographic density, circulating estrogens, and estrogens within the breast itself.

Until there is an accurate and precise means to measure breast density, even though it is widely acknowledged as important in the scientific literature, it will not be a widespread consideration in the clinic, says Dr. Kerlikowske. "The reason is that we need a reliable measure in the clinic, and clinicians need to be trained to interpret risk information that includes a breast density measure."

She uses blood cholesterol and bone mineral density tests to illustrate the point. "When I order one of these tests on a woman, I get a printout that tells me what her score is, where she is in relation to women her age, and what I should do in terms of an intervention," she explains. "We need cost-effectiveness analyses to figure out the threshold for when a woman's breast cancer risk warrants clinical intervention - a different screening procedure, or chemoprevention, for example. Clinicians need to know the threshold of risk that requires an intervention."

They also need a measure of breast density that is more quantitative than the subjective BI-RADS system, she says. To this end, she and colleagues at UCSF are pilot-testing a new technology that calculates volumetric measurements of breast density using standard mammogram equipment. "That's where the future lies, and that's when you'll see breast density more widely used in the clinic," she says.

The conversation about breast density and cancer risk will principally be between researchers and clinicians until the issues surrounding density measurement and sub-groups of women who have dense breasts, and thus higher risk, get sorted out. But it isn't too early, some researchers advise, for women to discuss the matter with their doctors if they have concerns. This may be particularly important, says Dr. Taplin, for women who have persistent lumps but a negative mammogram.

—Brittany Moya del Pino

|