Calcium: What is it?Calcium, the most abundant mineral in the human body, has several important functions. More than 99% of total body calcium is stored in the bones and teeth where it functions to support their structure [1]. The remaining 1% is found throughout the body in blood, muscle, and the fluid between cells. Calcium is needed for muscle contraction, blood vessel contraction and expansion, the secretion of hormones and enzymes, and sending messages through the nervous system [2]. A constant level of calcium is maintained in body fluid and tissues so that these vital body processes function efficiently.

Bone undergoes continuous remodeling, with constant resorption (breakdown of bone) and deposition of calcium into newly deposited bone (bone formation) [2]. The balance between bone resorption and deposition changes as people age. During childhood there is a higher amount of bone formation and less breakdown. In early and middle adulthood, these processes are relatively equal. In aging adults, particularly among postmenopausal women, bone breakdown exceeds its formation, resulting in bone loss, which increases the risk for osteoporosis (a disorder characterized by porous, weak bones) [2].

What is the recommended intake for calcium?Recommendations for calcium are provided in the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) developed by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academy of Sciences. Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) is the general term for a set of reference values used for planning and assessing nutrient intakes of healthy people. Three important types of reference values included in the DRIs are Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA), Adequate Intakes (AI), and Tolerable Upper Intake Levels (UL). The RDA recommends the average daily intake that is sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97-98%) healthy individuals in each age and gender group. An AI is set when there is insufficient scientific data available to establish a RDA. AIs meet or exceed the amount needed to maintain a nutritional state of adequacy in nearly all members of a specific age and gender group. The UL, on the other hand, is the maximum daily intake unlikely to result in adverse effects. It is listed in the section "Is there health risk of too much calcium?" of this fact sheet.

For calcium, the recommended intake is listed as an Adequate Intake (AI), which is a recommended average intake level based on observed or experimentally determined levels. Table 1 contains the current recommendations for calcium for infants, children and adults.

Table 1: Recommended Adequate Intake by the IOM for Calcium| Male and Female Age | Calcium (mg/day) | Pregnancy & Lactation |

|---|

| 0 to 6 months | 210 | N/A | | 7 to 12 months | 270 | N/A | | 1 to 3 years | 500 | N/A | | 4 to 8 years | 800 | N/A | | 9 to 13 years | 1300 | N/A | | 14 to 18 years | 1300 | 1300 | | 19 to 50 years | 1000 | 1000 | | 51+ years | 1200 | N/A |

*mg=milligrams

Source: [2]

There is a widespread concern that Americans are not meeting the recommended intake for calcium. According to the Continuing Survey of Food Intakes of Individuals (CSFII 1994-96), the following percentage of Americans are not meeting their recommended intake for calcium [3]:44% boys and 58% girls ages 6-1164% boys and 87% girls ages 12-1955% men and 78% of women ages 20+

What foods provide calcium?In the United States (U.S.), milk, yogurt and cheese are the major contributors of calcium in the typical diet [4]. The inadequate intake of dairy foods may explain why some Americans are deficient in calcium since dairy foods are the major source of calcium in the diet [4]. The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Food Guide Pyramid recommends that individuals two years and older eat 2-3 servings of dairy products per day. A serving is equal to:1 cup (8 fl oz) of milk8 oz of yogurt1.5 oz of natural cheese (such as Cheddar)2.0 oz of processed cheese (such as American)

A variety of non-fat and reduced fat dairy products that contain the same amount of calcium as regular dairy products are available in the U.S. today for individuals concerned about saturated fat content from regular dairy products.

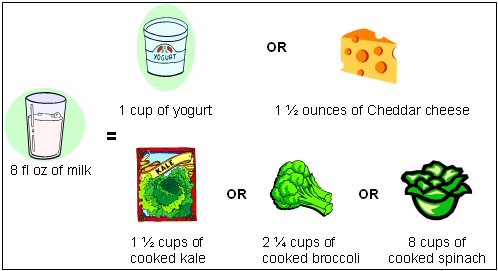

Although dairy products are the main source of calcium in the U.S. diet, other foods also contribute to overall calcium intake. Individuals with lactose intolerance (those who experience symptoms such as bloating and diarrhea because they cannot completely digest the milk sugar lactose) and those who are vegan (people who consume no animal products) tend to avoid or completely eliminate dairy products from their diets [2]. Thus, it is important for these individuals to meet their calcium needs with alternative calcium sources if they choose to avoid or eliminate dairy products from their diet. Foods such as Chinese cabbage, kale and broccoli are other alternative calcium sources [2]. Although most grains are not high in calcium (unless fortified), they do contribute calcium to the diet because they are consumed frequently [2]. Additionally, there are several calcium-fortified food sources presently available, including fruit juices, fruit drinks, tofu and cereals. Figure 1 compares portion sizes of various foods that provide the amount of calcium in one cup of milk. This figure takes into account that calcium absorption varies among foods. Certain plant-based foods such as some vegetables contain substances which can reduce calcium absorption. Thus, you may have to eat several servings of certain foods such as spinach to obtain the same amount of calcium in one cup of milk, which is not only calcium-rich but also contains calcium in an easily absorbable form. Table 2 contains additional listings of food sources of calcium.

Figure 1: Calcium Content of 8 fl oz of Milk Compared to Other Food Sources of Calcium

Source: [5]

Table 2: Selected Food Sources of Calcium [6-8]| Food | Calcium (mg) | % DV* | | Yogurt, plain, low fat, 8 oz. | 415 | 42% | | Yogurt, fruit, low fat, 8 oz. | 245-384 | 25%-38% | | Sardines, canned in oil, with bones, 3 oz. | 324 | 32% | | Cheddar cheese, 1 ½ oz shredded | 306 | 31% | | Milk, non-fat, 8 fl oz. | 302 | 30% | | Milk, reduced fat (2% milk fat), no solids, 8 fl oz. | 297 | 30% | | Milk, whole (3.25% milk fat), 8 fl oz | 291 | 29% | | Milk, buttermilk, 8 fl oz. | 285 | 29% | | Milk, lactose reduced, 8 fl oz.** | 285-302 | 29-30% | | Mozzarella, part skim 1 ½ oz. | 275 | 28% | | Tofu, firm, made w/calcium sulfate, ½ cup*** | 204 | 20% | | Orange juice, calcium fortified, 6 fl oz. | 200-260 | 20-26% | | Salmon, pink, canned, solids with bone, 3 oz. | 181 | 18% | | Pudding, chocolate, instant, made w/ 2% milk, ½ cup | 153 | 15% | | Cottage cheese, 1% milk fat, 1 cup unpacked | 138 | 14% | | Tofu, soft, made w/calcium sulfate, ½ cup*** | 138 | 14% | | Spinach, cooked, ½ cup | 120 | 12% | | Instant breakfast drink, various flavors and brands, powder prepared with water, 8 fl oz. | 105-250 | 10-25% | | Frozen yogurt, vanilla, soft serve, ½ cup | 103 | 10% | | Ready to eat cereal, calcium fortified, 1 cup | 100-1000 | 10%-100% | | Turnip greens, boiled, ½ cup | 99 | 10% | | Kale, cooked, 1 cup | 94 | 9% | | Kale, raw, 1 cup | 90 | 9% | | Ice cream, vanilla, ½ cup | 85 | 8.5% | | Soy beverage, calcium fortified, 8 fl oz. | 80-500 | 8-50% | | Chinese cabbage, raw, 1 cup | 74 | 7% | | Tortilla, corn, ready to bake/fry, 1 medium | 42 | 4% | | Tortilla, flour, ready to bake/fry, one 6" diameter | 37 | 4% | | Sour cream, reduced fat, cultured, 2 Tbsp | 32 | 3% | | Bread, white, 1 oz | 31 | 3% | | Broccoli, raw, ½ cup | 21 | 2% | | Bread, whole wheat, 1 slice | 20 | 2% | | Cheese, cream, regular, 1 Tbsp | 12 | 1% |

*DV=Daily Value

**Content varies slightly according to fat content; average =300 mg calcium

*** Calcium values are only for tofu processed with a calcium salt. Tofu processed with a non-calcium salt will not contain significant amounts of calcium.

Daily Values (DV) were developed to help consumers determine if a typical serving of a food contains a lot or a little of a specific nutrient. The DV for calcium is based on 1000 mg. The percent DV (% DV) listed on the Nutrition Facts panel of food labels tells you what percentages of the DV are provided in one serving. For instance, if you consumed a food that contained 300 mg of calcium, the DV would be 30% for calcium on the food label.

A food providing 5% of the DV or less is a low source while a food that provides 10-19% of the DV is a good source and a food that provides 20% of the DV or more is an excellent source for a nutrient. For foods not listed in this table, please refer to the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Nutrient Database Web site: http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/cgi-bin/nut_search.pl.

Helping hints for meeting your calcium needsAs the 2000 Dietary Guidelines for Americans states, "Different foods contain different nutrients and other healthful substances. No single food can supply all the nutrients in the amounts you need" [9]. For more information about building a healthful diet, refer to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans http://www.usda.gov/cnpp/DietGd.pdf and the US Department of Agriculture's Food Guide Pyramid http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/Fpyr/pyramid.html [9,10].

The following are strategies and tips to help you meet your calcium needs each day:Use low fat or fat free milk instead of water in recipes such as pancakes, mashed potatoes, pudding and instant, hot breakfast cereals.Blend a fruit smoothie made with low fat or fat free yogurt for a great breakfast.Sprinkle grated low fat or fat free cheese on salad, soup or pasta.Choose low fat or fat free milk instead of carbonated soft drinks.Serve raw fruits and vegetables with a low fat or fat free yogurt based dip.Create a vegetable stir-fry and toss in diced calcium-set tofu.Enjoy a parfait with fruit and low fat or fat free yogurt.Complement your diet with calcium-fortified foods such as certain cereals, orange juice and soy beverages.

What affects calcium absorption and excretion?Calcium absorption refers to the amount of calcium that is absorbed from the digestive tract into our body's circulation. Calcium absorption can be affected by the calcium status of the body, vitamin D status, age, pregnancy and plant substances in the diet. The amount of calcium consumed at one time such as in a meal can also affect absorption. For example, the efficiency of calcium absorption decreases as the amount of calcium consumed at a meal increases.

- Age:

Net calcium absorption can be as high as 60% in infants and young children, when the body needs calcium to build strong bones [2,11]. Absorption slowly decreases to 15-20% in adulthood and even more as one ages [2,11,12]. Because calcium absorption declines with age, recommendations for dietary intake of calcium are higher for adults ages 51 and over.

- Vitamin D:

Vitamin D helps improve calcium absorption. Your body can obtain vitamin D from food and it can also make vitamin D when your skin is exposed to sunlight. Thus, adequate vitamin D intake from food and sun exposure is essential to bone health. The Office of Dietary Supplement's vitamin D fact sheet provides more information: http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/vitamind.asp.

- Pregnancy:

Current calcium recommendations for nonpregnant women are also sufficient for pregnant women because intestinal calcium absorption increases during pregnancy [2]. For this reason, the calcium recommendations established for pregnant women are not different than the recommendations for women who are not pregnant.

- Plant substances:

Phytic acid and oxalic acid, which are found naturally in some plants, may bind to calcium and prevent it from being absorbed optimally. These substances affect the absorption of calcium from the plant itself not the calcium found in other calcium-containing foods eaten at the same time [6]. Examples of foods high in oxalic acid are spinach, collard greens, sweet potatoes, rhubarb, and beans. Foods high in phytic acid include whole grain bread, beans, seeds, nuts, grains, and soy isolates [2]. Although soybeans are high in phytic acid, the calcium present in soybeans is still partially absorbed [2,13]. Fiber, particularly from wheat bran, could also prevent calcium absorption because of its content of phytate. However, the effect of fiber on calcium absorption is more of a concern for individuals with low calcium intakes. The average American tends to consume much less fiber per day than the level that would be needed to affect calcium absorption.

Calcium excretion refers to the amount of calcium eliminated from the body in urine, feces and sweat. Calcium excretion can be affected by many factors including dietary sodium, protein, caffeine and potassium.

- Sodium and protein:

Typically, dietary sodium and protein increase calcium excretion as the amount of their intake is increased [5,14]. However, if a high protein, high sodium food also contains calcium, this may help counteract the loss of calcium.

- Potassium:

Increasing dietary potassium intake (such as from 7-8 servings of fruits and vegetables per day) in the presence of a high sodium diet (>5100 mg/day, which is more than twice the Tolerable Upper Intake Level of 2300 mg for sodium per day) may help decrease calcium excretion particularly in postmenopausal women [15,16].

- Caffeine:

Caffeine has a small effect on calcium absorption. It can temporarily increase calcium excretion and may modestly decrease calcium absorption, an effect easily offset by increasing calcium consumption in the diet [17]. One cup of regular brewed coffee causes a loss of only 2-3 mg of calcium easily offset by adding a tablespoon of milk [14]. Moderate caffeine consumption, (1 cup of coffee or 2 cups of tea per day), in young women who have adequate calcium intakes has little to no negative effects on their bones [18].

Other factors:

- Phosphorus: The effect of dietary phosphorus on calcium is minimal. Some researchers speculate that the detrimental effects of consuming foods high in phosphate such as carbonated soft drinks is due to the replacement of milk with soda rather than the phosphate level itself [19,20].

- Alcohol: Alcohol can affect calcium status by reducing the intestinal absorption of calcium [21]. It can also inhibit enzymes in the liver that help convert vitamin D to its active form which in turn reduces calcium absorption [3]. However, the amount of alcohol required to affect calcium absorption is unknown. Evidence is currently conflicting whether moderate alcohol consumption is helpful or harmful to bone.

In summary, a variety of factors that may cause a decrease in calcium absorption and/or increase in calcium excretion may negatively affect bone health.

Calcium's role in health and disease preventionCalcium and bone health

Your bones are living tissues and continue to change throughout life. During childhood and adolescence, bones increase in size and mass. Bones continue to add more mass until around age 30, when peak bone mass is reached. Peak bone mass is the point when the maximum amount of bone is achieved. Because bone loss, like bone growth, is a gradual process, the stronger your bones are at age 30, the more your bone loss will be delayed as you age. Therefore, it is particularly important to consume adequate calcium and vitamin D throughout infancy, childhood, and adolescence. It is also important to engage in weight-bearing exercise to maximize bone strength and bone density (amount of bone tissue in a certain volume of bone) to help prevent osteoporosis later in life. Weight bearing exercise is the type of exercise that causes your bones and muscles to work against gravity while they bear your weight. Resistance exercises such as weight training are also important because they help to improve muscle mass and bone strength.

| Examples of weight bearing exercisewalkingrunningdancingaerobicsskating | Examples of NON-weight bearing exerciseswimmingbicyclingwater aerobics |

Osteoporosis is a disorder characterized by porous, fragile bones. It is a serious public health problem for more than 10 million Americans, 80% of whom are women. Another 34 million Americans have osteopenia, or low bone mass, which precedes osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is a concern because of its association with fractures of the hip, vertebrae, wrist, pelvis, ribs, and other bones [22]. Each year, Americans suffer from 1.5 million fractures because of osteoporosis [23].

Osteoporosis and osteopenia can result from dietary factors such as [11,24,25]:chronically low calcium intakelow vitamin D intakepoor calcium absorptionexcess calcium excretion

When calcium intake is low or calcium is poorly absorbed, bone breakdown occurs because the body must use the calcium stored in bones to maintain normal biological functions such as nerve and muscle function. Bone loss also occurs as a part of the aging process. A prime example is the loss of bone mass observed in post-menopausal women because of decreased amounts of the hormone estrogen. Researchers have identified many factors that increase the risk for developing osteoporosis. These factors include being female, thin, inactive, of advanced age, cigarette smoking, excessive intake of alcohol, and having a family history of osteoporosis [26].

In 1993 the FDA authorized a health claim for food labels on calcium and osteoporosis in response to scientific evidence that an inadequate calcium intake is one factor that can lead to low peak bone mass and is considered a risk factor for osteoporosis [27]. The claim states that "adequate calcium intake throughout life is linked to reduced risk of osteoporosis through the mechanism of optimizing peak bone mass during adolescence and early adulthood and decreasing bone loss later in life".

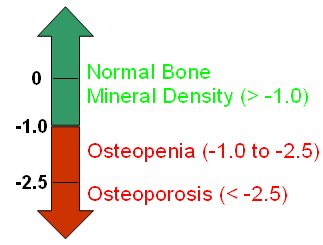

Various bone mineral density (BMD) tests, including those that measure your hip, spine, wrist, finger, shin bone, and heel, can help determine bone mass. These tests provide a T-score which is a measure of bone mineral density that compares an individual's BMD to an optimal BMD of a 30 year old healthy adult. See Figure 2 below. A T-Score of -1.0 and above indicates normal bone density. A T-score of -1.0 to -2.5 indicates that a person is considered to have low bone mass (osteopenia). A score below -2.5 indicates osteoporosis [28].

Figure 2: Interpreting Bone Mineral Density Scores

Although osteoporosis affects people of different races, genders and ethnicities, women are at highest risk because their skeletons are smaller to start with and because of the accelerated bone loss that accompanies menopause. Adequate calcium and vitamin D intakes, as well as weight bearing exercise are critical to the development and maintenance of healthy bone throughout the lifecycle. Older adults should strive to maintain recommended daily calcium intakes as well as an adequate vitamin D intake.

Calcium and high blood pressure

Some observational studies (type of research study in which the treatment/intervention is observed and not controlled by the researchers) and experimental studies (type of research study in which the researchers control the treatments/interventions and that are assigned to participants) indicate that individuals who eat a vegetarian diet high in minerals (including calcium, magnesium and potassium) and fiber, and low in fat, tend to have reduced blood pressure [29-31].

Findings from some clinical trials (a specific type of experimental study) used to evaluate the effects of one or more treatments/interventions in humans) indicate that an increased calcium intake lowers blood pressure and the risk of hypertension (high blood pressure) [32,33]. However, the results of some studies produced small and inconsistent reductions in blood pressure. One reason for these results is because these research studies tended to test the effect of single nutrients rather than foods on blood pressure.

To help test the combined effect of nutrients including calcium from food on blood pressure, a study was conducted to investigate the impact of various dietary eating patterns on blood pressure. This study titled "Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)" was reported in 1997 by the National, Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. It investigated the effect of various eating patterns on lowering blood pressure. The DASH study was a multi-center research trial where food was provided to over 450 adults. It examined the effects of three different diets on high blood pressure: a control, "typical American" diet and two modified diets (high fruits-and-vegetables and a combination "DASH" diet - high in fruits, vegetables, and low fat dairy). See Table 3 for a comparison of some of the components of the three diets.

Table 3: Comparison of the Three Diets Tested in the "DASH" Study| Diet Components | Fruit & Vegetable Servings | Lowfat Dairy Servings | Calcium (mg) | Fat (% of total calories) | Sodium (mg) | Cholesterol (mg) | Fiber (g) | | Control "Typical American" diet | 3.5 | 0.1 | 450 | 37 | 3000 | 300 | 9 | | Fruits-and-Vegetables diet | 8.5 | 0.0 | 450 | 37 | 3000 | 300 | 31 | | Combination "DASH" diet | 9.5 | 2.0 | 1240 | 27 | 3000 | 150 | 31 |

Of the three diets tested, the combination "DASH" diet resulted in the greatest decrease in blood pressure [34]. Thus, this finding from a large and carefully executed clinical trial helped demonstrate that the combination "DASH" diet, with increased calcium, decreased blood pressure [35]. A number of further studies have been done, all showing a similar relationship between increasing calcium intakes and decreased blood pressure [36]. A study conducted after the original "DASH" study, referred to as the "DASH-Sodium" study showed that the DASH diet without sodium restriction provided as much blood pressure reduction as did severe sodium restriction on the control diet (1500 mg sodium/day) [37]. Overall it appears that consuming an adequate intake of fruits and vegetables as well as calcium from low fat dairy products plays a significant role in controlling blood pressure. Additional information and sample DASH menu plans are available on the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute's Web site (http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/hbp/dash/index.htm).

Calcium and cancer

Colorectal cancer

The relationship between calcium intake and the risk of colon cancer has not been conclusively determined. Observational and experimental research studies investigating the role calcium plays in the prevention of colon cancer show mixed results. Some studies suggest that increased intakes of dietary (low fat dairy sources) and supplemental calcium are associated with a decreased risk of colon cancer [38-41]. Supplementation with calcium carbonate is reported to lead to reduced risk of adenomas (nonmalignant tumors) in the colon, a precursor to colon cancer, but it is not known if this will ultimately translate into reduced cancer risk [42]. Another study reported on the association between diet and colon cancer history in 135,000 men and women participating in two large health surveys, the Nurses' Health Study and the Physicians' Health Study. The authors found that those who consumed 700 to 800 mg calcium per day had a 40 to 50% lower risk of developing left side colon cancer [43]. However, a few other observational studies found inconclusive evidence regarding any association of calcium intake with colon cancer [44-46]. Although some research findings indicate a protective effect of calcium or low fat dairy foods against colon cancer, further studies are necessary to confirm this role for calcium.

Prostate cancer

There is some evidence to suggest that higher calcium (ranging from 600 mg to >2000 mg of calcium) and/or dairy intakes (>2.5 servings) may be associated with the development of prostate cancer [47-50]. However, these studies are observational in nature rather than clinical trials and cannot establish a definite causal relationship between calcium and prostate cancer. Other findings only show a weak relationship, no relationship at all or the opposite relationship between calcium and prostate cancer [51-54]. Thus, the relationship between calcium intake, dairy intake and prostate cancer risk remains unclear. At the present time, it is recommended that men ages 19 and over consume a "modest" intake of calcium ranging from 1000-1200 mg per day and maintain an intake below the upper tolerable limit (2500 mg) [1].

Calcium and kidney stones

Kidney stones are crystallized deposits of calcium and other minerals in the urinary tract. Calcium oxalate stones are the most common form of kidney stones in the US. High calcium intakes or high calcium absorption were previously thought to contribute to the development of kidney stones. However, more recent studies show that high dietary calcium intakes actually decrease the risk for kidney stones [55-57]. Other factors such as high oxalate intake and reduced fluid consumption appear to be more of a risk factor in the formation of kidney stones than calcium in most individuals [58].

Calcium and weight management

Several studies, primarily observational in nature, have linked higher calcium intakes to lower body weights or less weight gain over time [59-62]. Two explanations have been proposed for how calcium may help to regulate body weight. First, high-calcium intakes may reduce calcium concentrations in fat cells by lowering the production of two hormones (parathyroid hormone and an active form of vitamin D), which in turn increases fat breakdown in these cells and discourages its accumulation [61]. In addition, calcium from food or supplements may bind to small amounts of dietary fat in the digestive tract and prevent its absorption, carrying the fat (and the calories it would otherwise provide) out in the feces [61,63].

Dairy products in particular may contain additional components that have even greater effects on body weight than their calcium content alone would suggest [64-69]. Three small, recently published clinical trials show that calcium-rich dairy products may help obese individuals following reduced-calorie diets to lose some excess weight and fat [67-69]. In one trial, 32 obese adults were randomized to one of three groups: eating a standard diet providing 400-500 mg calcium, eating a standard diet supplemented with 800 mg calcium, and eating a diet with 3 servings/day of dairy products to provide 1,200-1,300 mg calcium [67]. The subjects ate 500 fewer calories a day over the 24 weeks of the study. All lost weight and body fat, but those taking the calcium supplements lost significantly more than subjects eating the unsupplemented standard diet, and those on the high-dairy diet lost by far the most. Dairy products also favorably affected body composition in a small group of obese African-American adults who followed a weight-maintenance program for 24 weeks [69]. Subjects who ate 3 servings/day of dairy products, which increased calcium intakes to 1,200 mg/day, lost significantly more fat (both total body and abdominal) and preserved lean body mass as compared to those who consumed less than one daily serving of these foods and 500 mg/day total calcium.

Despite the hopeful results of these studies, other recent clinical trials make it clear that the involvement of calcium and dairy products in weight regulation and body composition is complex, inconsistent, and not well understood [61,70]. For example, one study in young women of normal body weight found that higher intakes of dairy products had no effect on weight or fat mass over the course of one year [71]. Another study in which 100 overweight and obese pre- and post-menopausal women on reduced-calorie diets received either 1,000 mg/day calcium or a placebo for 25 weeks found no significant differences in weight or fat loss between the groups [72]. Similar results were obtained in a study of 1,471 postmenopausal women (somewhat overweight on average) who were randomly assigned to take 1,000 mg/day calcium or a placebo for 30 months, though there was a trend toward greater weight loss in those who took the calcium supplement and whose calcium intakes from food averaged less than 600 mg/day [73]. Clearly, larger clinical trials are needed to better assess the effects of calcium and dairy products on body weight, composition, and fat distribution [61,74].

When can a calcium deficiency occur?Inadequate calcium intake, decreased calcium absorption, and increased calcium loss in urine can decrease total calcium in the body, with the potential of producing osteoporosis and the other consequences of chronically low calcium intake. If an individual does not consume enough dietary calcium or experiences rapid losses of calcium from the body, calcium is withdrawn from their bones in order to maintain calcium levels in the blood.

Signs of calcium deficiency

Because circulating blood calcium levels are tightly regulated in the bloodstream, hypocalcemia (low blood calcium) does not usually occur due to low calcium intake, but rather results from a medical problem or treatment such as renal failure, surgical removal of the stomach (which significantly decreases calcium absorption), and use of certain types of diuretics (which result in increased loss of calcium and fluid through urine). Simple dietary calcium deficiency produces no signs at all. Hypocalcemia can cause numbness and tingling in fingers, muscle cramps, convulsions, lethargy, poor appetite, and mental confusion [1]. It can also result in abnormal heart rhythms and even death. Individuals with medical problems that result in hypocalcemia should be under a medical doctor's care and receive specific treatment aimed at normalizing calcium levels in the blood. [Please note that the symptoms described here may be due to a medical condition other than hypocalcemia.] It is important to consult a health professional if you experience any of these symptoms.

Who may need extra calcium to prevent a deficiency?

Post-Menopausal Women

Menopause often leads to increases in bone loss with the most rapid rates of bone loss occurring during the first five years after menopause [75]. Drops in estrogen production after menopause result in increased bone resorption, and decreased calcium absorption [12,76,77]. Annual decreases in bone mass of 3-5% per year are often seen during the years immediately following menopause, with decreases less than 1% per year seen after age 65 [78]. Two studies are in agreement that increased calcium intakes during menopause will not completely offset menopause bone loss [79,80].

Hormone therapy (HT), previously known as hormone replacement therapy (HRT), with sex hormones such as estrogen and progesterone, helps to prevent osteoporosis and fractures. However, some medical groups and professional societies such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, The North American Menopause Society and The American Society for Bone and Mineral Research recommend that postmenopausal women consider using other agents such as bisphosphonates (medication used to slow or stop bone-resorption) because of potential health risks of HT if combination HT (estrogen and progestin) is solely being administered to prevent or treat osteoporosis [81-83]. Postmenopausal women using combination HT to reduce bone loss should consult with their physician about the risks and benefits of estrogen therapy for their health.

Estrogen therapy works to restore postmenopausal bone remodeling levels back to those of premenopause, leading to a lower rate of bone loss [76]. Estrogen appears to interact with supplemental calcium by increasing calcium absorption in the gut. However, including adequate amounts of calcium in the diet may help slow the rate of bone loss for all women.

Amenorrheic Women and the Female Athlete Triad

Amenorrhea is the condition when menstrual periods stop or fail to initiate in women who are of childbearing age. Secondary amenorrhea is the absence of three or more consecutive menstrual cycles after menarche occurs (first menstrual period). The secondary type of amenorrhea can be induced by exercise in athletes and is referred to as "athletic amenorrhea". Potential causes of athletic amenorrhea include low body weight and low percent body fat, rapid weight loss, sudden onset of vigorous exercise, disordered eating and stress [84]. Amenorrhea results from decreases in circulating estrogen, which then negatively affect calcium balance [2]. Studies comparing healthy women with normal menstrual cycles to amenorrheic women with anorexia nervosa (a type of disordered eating) found decreased levels of calcium absorption, a higher urinary calcium excretion, and a lower rate of bone formation in women with anorexia [85].

The condition "female athlete triad" refers to the combination of disordered eating, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis. Exercise-induced amenorrhea has been shown to result in decreases in bone mass [86,87]. In female athletes, low bone mineral density, menstrual irregularities, dietary factors, and a history of prior stress fractures are associated with an increased risk of future stress fractures [88]. Stress fractures can severely impact health and cause financial burden, especially in physically active females such women in the military [90]. Thus, it is important for amenorrheic women to maintain the recommended Adequate Intake for calcium.

Lactose Intolerant Individuals

Lactose maldigestion (or "lactase non-persistence") describes the inability of an individual to completely digest lactose, the naturally occurring sugar in milk. Lactose intolerance refers to the symptoms that occur when the amount of lactose exceeds the ability of an individual's digestive tract to break down lactose. In the US, approximately 25% of all adults have a limited ability to digest lactose. Lactose maldigestion varies by ethnicity, with a prevalence of 85% in Asians, 50% in African Americans, and 10% in Caucasians [90-92].

Symptoms of lactose intolerance include bloating, flatulence, and diarrhea after consuming large amounts of lactose (such as the amount in 1 quart of milk) [93]. Lactose maldigesters may be at risk for calcium deficiency, not due to an inability to absorb calcium, but rather from the avoidance of dairy products [2,94,95]. Although some lactose maldigesters avoid dairy products, others are able to consume moderate amounts of lactose, such as the amount in an 8-oz glass of milk. Some individuals may be able to consume two 8-oz glasses of milk a day if they do so at different meals [96-98].

Symptoms of lactose intolerance vary from individual to individual depending on the amount of lactose consumed, history of previous consumption of foods with lactose and the type of meal with which the lactose is consumed [99-102]. Drinking milk with a meal helps reduce symptoms of lactose intolerance substantially. In addition, regularly eating foods (e.g. daily for 2-3 weeks) with lactose (such as milk) can help the body adapt to the lactose and thus reduce symptoms of lactose intolerance [99,101,103]. Other dietary options for lactose maldigesters include choosing aged cheeses (such as Cheddar and Swiss) which contain little lactose, yogurt which contains live active cultures that aid in lactose digestion, or lactose reduced and lactose free milk.

If an individual is a lactose maldigester and chooses to avoid dairy products, it is important for them to include non-dairy sources of calcium in their daily diet (see Table 2 for a listing of selected food sources of calcium) or consider taking a calcium supplement to help meet their recommended calcium needs.

Vegetarians

There are several types of vegetarian eating practices. Individuals may choose to include some animal products (ovo-vegetarian, lacto-vegetarian, lacto-ovo vegetarian, pesco-vegetarian) or no animal products (vegan) in their diet. Calcium intakes between lacto-ovo-vegetarians (those who consume eggs and dairy products) and non-vegetarians have been shown to be similar [104,105]. Calcium absorption may be reduced in vegetarians because they eat more plant foods containing oxalic and phytic acids, compounds which interfere with calcium absorption [2]. However, vegetarian diets that contain less protein may reduce calcium excretion [1]. Yet, vegans may be at increased risk for inadequate intake of calcium because of their lack of consumption of dairy products [106]. Therefore, it is important for vegans to include adequate amounts of non-dairy sources of calcium in their daily diet (see Table 2) or consider taking a calcium supplement to meet their recommended calcium intake. Furthermore, while early studies found vegetarian diets to be beneficial for bone health, more recent studies have found no benefits or even the opposite effect [107].

Is there a health risk of too much calcium?The Tolerable Upper Limit (UL) is the highest level of daily intake of calcium from food, water and supplements that is likely to pose no risks of adverse health effects to almost all individuals in the general population [2]. The UL for children and adults ages 1 year and older (including pregnant and lactating women) is 2500 mg/day. It was not possible to establish a UL for infants under the age of 1 year.

While low intakes of calcium can result in deficiency and undesirable health conditions, excessively high intakes of calcium can also have adverse effects. Adverse conditions associated with high calcium intakes are hypercalcemia (elevated levels of calcium in the blood), impaired kidney function and decreased absorption of other minerals [2]. Hypercalcemia can also result from excess intake of vitamin D, such as from supplement overuse at levels of 50,000 IU or higher [1]. However, hypercalcemia from diet and supplements is very rare. Most cases of hypercalcemia occur as a result of malignancy - especially in the advanced stages.

Another concern with high calcium intakes is the potential for calcium to interfere with the absorption of other minerals, iron, zinc, magnesium, and phosphorus [108-111].

Most Americans should consider their intake of calcium from all foods including fortified ones before adding supplements to their diet to help avoid the risk of reaching levels at or near the UL for calcium (2500 mg). If you need additional assistance regarding your calcium needs, consider checking with a physician or registered dietitian.

Calcium and Medication InteractionsCalcium supplements have the potential to interact with several prescription and over the counter medications. Further information about these interactions is described below. Some examples of medications that may interact with calcium include:

- digoxin

- fluroquinolones

- levothyroxine

- antibiotics in tetracycline family

- tiludronate disodium

- anticonvulsants such as phenytoin

- thiazide, type of diuretic

- glucocorticoids

- mineral oil or stimulant laxatives

- aluminum or magnesium containing antacids

Calcium supplements may decrease levels of the drug digoxin, a medication given to heart patients [112]. The interaction between calcium and vitamin D supplements and digoxin may also increase the risk of hypercalcemia. Calcium supplements also interact with fluoroquinolones (a class of antibiotics including ciprofloxacin), levothyroxine (thyroid hormone) used to treat thyroid deficiency, antibiotics in the tetracycline family, tiludronate disodium (a drug used to treat Paget's disease), and phenytoin (an anti-convulsant drug). In all of these cases, calcium supplements decrease the absorption of these drugs when the two are taken at the same time [112,113].

Thiazide, and diuretics similar to thiazide, can interact with calcium carbonate and vitamin D supplements to increase the chances of developing hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria (elevated levels of calcium in urine) [113]. Aluminum and magnesium antacids can both increase urinary calcium excretion. Mineral oil and stimulant laxatives can both decrease dietary calcium absorption. Furthermore, glucocorticoids (for example: prednisone) can cause calcium depletion and eventually osteoporosis, when used for more than a few weeks [113].

Supplemental sources of calciumThe 2000 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend that individuals consume a variety of foods to meet their nutrient needs since no single food can supply all the nutrients in the amounts needed by an individual [114]. However, for some people it may be necessary to take supplements in order to meet the recommended intakes for calcium. In 2002, calcium supplements were the number one selling mineral supplement and the 3rd highest selling supplement overall in the U.S. nutrition industry totaling approximately $877 million in sales [115].

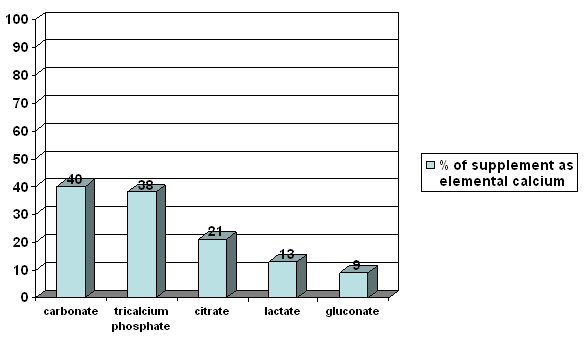

The two main forms of calcium found in supplements are carbonate and citrate. Calcium carbonate is the most common because it is inexpensive and convenient. The absorption of calcium citrate is similar to calcium carbonate. For instance, a calcium carbonate supplement contains 40% calcium while a calcium citrate supplement only contains 21% calcium. However, you have to take more pills of calcium citrate to get the same amount of calcium as you would get from a calcium carbonate pill since citrate is a larger molecule than carbonate. One advantage of calcium citrate over calcium carbonate is better absorption in those individuals who have decreased stomach acid. Calcium citrate malate is a form of calcium used in the fortification of certain juices and is also well absorbed [116]. Other forms of calcium in supplements or fortified foods include calcium gluconate, lactate, and phosphate.

The amount of calcium your body obtains from various supplements depends on the amount of elemental calcium in the tablet. The amount of elemental calcium is the amount of calcium that actually is in the supplement. Calcium absorption also depends on the total amount of calcium consumed at one time and whether the calcium is taken with food or on an empty stomach. Absorption from supplements is best in doses 500 mg or less because the percent of calcium absorbed decreases as the amount of calcium in the supplement increases [117,118]. Therefore, someone taking 1000 mg of calcium in a supplement should take 500 mg twice a day instead of 1000 mg calcium at one time.

Some common complaints of calcium supplement use are gas, bloating and constipation. If you have such symptoms, you may want to spread the calcium dose out throughout the day, change supplement brands, take the supplement with meals and/or check with your pharmacist or health care provider.

Figure 3 compares the amount of calcium (elemental calcium) found in some different forms of calcium supplements [119].

Figure 3: Comparison of Calcium Content of Various Supplements

|

|

|

Posted Date:

7/12/2004 |

Updated:

12/4/2008 4:10 PM |

|

|

- Shils ME. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 9th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

- Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D and Fluoride. Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 1997.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. Results from the United States Department of Agriculture's 1994-96 Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals/Diet and Health Knowledge Survey. 1994-96.

- Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM, Cook A, Kahle LL. Dietary sources of nutrients among US adults. J Am Diet Assoc 1998;98:537-47.

- Weaver CM, Proulx WR, Heaney RP. Choices for achieving adequate dietary calcium with a vegetarian diet. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;70:543S-8S.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture ARS. USDA Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 16. Nutrient Data Laboratory Home Page. 2003. http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp.

- Pennington J, Bowes A, Church H. Bowes & Church's Food Values of Portions Commonly Used. 17th ed: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publishers, 1998.

- Heaney RP, Dowell MS, Rafferty K, Bierman J. Bioavailability of the calcium in fortified soy imitation milk, with some observations on method. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;71:1166-69.

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Home and Garden Bulletin No. 232. 2000.

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. Food Guide Pyramid. 1992 (slightly revised 1996). http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/Fpyr/pyramid.html.

- NIH. National Institutes of Health consensus statement: Optimal calcium intake. 1994;12:1-31.

- Heaney RP, Recker RR, Stegman MR, Moy AJ. Calcium absorption in women: Relationships to calcium intake, estrogen status, and age. J Bone Miner Res 1989;4:469-75.

- Heaney RP, Weaver CM, Fitzsimmons ML. Soybean phytate content: Effect on calcium absorption. Am J Clin Nutr 1991;53:745-47.

- Heaney RP. Bone mass, nutrition, and other lifestyle factors. Nutr Rev 1996;54:S3-S10.

- Sellmeyer DE, Schloetter M, Sebastian A. Potassium citrate prevents increased urine calcium excretion and bone resorption induced by a high sodium chloride diet. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:2008-12.

- Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate. Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2004.

- Barrett-Connor E, Chang JC, Edelstein SL. Coffee-associated osteoporosis offset by daily milk consumption. JAMA 1994;271:280-83.

- Massey LK, Whiting SJ. Caffeine, urinary calcium, calcium metabolism, and bone. J Nutr 1993;123:1611-14.

- Calvo MS. Dietary phosphorus, calcium metabolism and bone. J Nutr 1993;123:1627-1633.

- Heaney RP, Rafferty K. Carbonated beverages and urinary calcium excretion. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;74:343-47.

- Hirsch PE, Peng TC. Effects of alcohol on calcium homeostasis and bone. In: Anderson J, Garner S, eds. Calcium and Phosphorus in Health and Disease. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 1996:289-300.

- NIH. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. NIH Consensus Statement Online 2000 March 27-29, 2000:1-36.

- Riggs BL, Melton L. The worldwide problem of osteoporosis: Insights afforded by epidemiology. Bone 1995;17:505S-511S.

- National Research Council. Recommended Dietary Allowances: 10th Edition. Washington, DC: National Academy Press 1989;Report of the subcommittee on the tenth edition of the RDAs, Food and Nutrition Board, and the Commission on Life Sciences.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2000: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office 1990;DHHS Publ. No (PHS) 91-50212:466-67.

- National Osteoporosis Foundation. NOF osteoporosis prevention - risk factors for osteoporosis. 2003. http://www.nof.org/prevention/risk.htm.

- Food and Drug Administration. Health Claims: calcium and osteoporosis. 1993. http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~lrd/cf101-72.html.

- National Osteoporosis Foundation. Bone mineral density testing: What the numbers mean. NOF, Bone Health Updates. 2001. http://www.nof.org/osteoporosis/bmdtest.htm.

- Rouse IL, Beilin LJ, Armstrong BK, Vandongen R. Blood-pressure-lowering effect of a vegetarian diet: controlled trial in normotensive subjects. Lancet 1983;1:5-10.

- Margetts BM, Beilin L, Armstrong BK, Vandongen R. Vegetarian diet in the treatment of mild hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. J Hypertens 1985:S429-31.

- Beilin LJ, Armstrong BK, Margetts BM, Rouse IL, Vandongen R. Vegetarian diet and blood pressure. Nephron 1987;47:37-41.

- Allender PS, Cutler JA, Follmann D, Cappuccio FP, Pryer J, Elliott P. Dietary calcium and blood pressure. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:825-831.

- Bucher HC, Cook RJ, Guyatt GH, et al. Effects of dietary calcium supplementation on blood pressure. JAMA 1996;275:1016-1022.

- Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1117-24.

- Miller GD, DiRienzo DD, Reusser M, McCarron D. Benefits of dairy product consumption on blood pressure in humans:A summary of the biomedical literature. J Am Coll Nutr 2000;19:147S-164S.

- McCarron D, Reusser M. Finding consensus in the dietary calcium-blood pressure debate. J Am Coll Nutr 1999;18:398S-405S.

- Vollmer W, Sacks FM, Ard J, et al. Effect of diet and sodium intake on blood pressure: subgroup analysis of the DASH-Sodium trial. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:1019-28.

- Slattery M, Edwards S, Boucher K, Anderson K, Caan B. Lifestyle and colon cancer: An Assessment of Factors Associated with Risk. Am J Epidemiol 1999;150:869-77.

- Kampman E, Slattery M, Bette C, Potter J. Calcium, vitamin D, sunshine exposure, dairy products, and colon cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control 2000;11:459-66.

- Holt P, Atillasoy E, Gilman J, et al. Modulation of abnormal colonic epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation by low-fat dairy foods. JAMA 1998;280:1074-79.

- Biasco G, Paganelli M. European trials on dietary supplementation for cancer prevention. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;889:152-156.

- Baron JA, Beach M, Mandel JS, et al. Calcium supplements for the prevention of colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med 1999;340:101-7.

- Wu K, Willett WC, Fuchs CS, Colditz GA, Giovannucci EL. Calcium intake and risk of colon cancer in women and men. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:437-46.

- Bergsma-Kadijk JA, van't Veer P, Kampman E, Burema J. Calcium does not protect against colorectal neoplasia. Epidemiology 1996;7:590-597.

- Cascinu S, Del Ferro E, Cioccolini P. Effects of calcium and vitamin supplementation on colon cancer cell proliferation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Invest 2000;18:411-416.

- Martinez ME, Willett WC. Calcium, vitamin D, and colorectal cancer: A review of epidemiologic evidence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1998;7:163-68.

- Chan JM, Stampfer MJ, Gann PH, Gaziano JM, Giovannucci EL. Dairy products, calcium, and prostate cancer risk in the Physicians Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;74:549-54.

- Giovannucci EL, Rimm EB, Wolk A, et al. Calcium and fructose intake in relation to risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Res 1998;58:442-447.

- Chan JM, Giovannucci E, Andersson SO, Yuen J, Adami HO, Wok A. Dairy products, calcium, phosphorous, vitamin D, and risk of prostate cancer (Sweden). Cancer Causes Control 1998;9:559-566.

- Chan JM, Giovannucci EL. Dairy products, calcium, and vitamin D and risk of prostate cancer. Epidemiol Rev 2001;23:87-92.

- Chan JM, Pietinen P, Virtanen M, et al. Diet and prostate cancer risk in a cohort of smokers, with a specific focus on calcium and phosphorus (Finland). Cancer Causes Control 2000;11:859-67.

- Schuurman AG, Van den Brandt PA, Dorant E, Goldbohm RA. Animal products, calcium and protein and prostate cancer risk in the Netherlands Cohort Study. Br J Cancer 1999;80:1107-13.

- Kristal AR, Stanford JL, Cohen JH, Wicklund K, Patterson RE. Vitamin and mineral supplement use is associated with reduced risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1999;8:887-92.

- Vlajinac HD, Marinkovic JM, Ilic MD, Kocev NI. Diet and prostate cancer: a case-control study. Eur J Cancer 1997;33:101-7.

- Curhan G, Willett WC, Rimm E, Stampher MJ. A prospective study of dietary calcium and other nutrients and the risk of symptomatic kidney stones. N Engl J Med 1993;328:833-8.

- Bihl G, Meyers A. Recurrent renal stone disease-advances in pathogenesis and clinical management. Lancet 2001;358:651-56.

- Hall WD, Pettinger M, Oberman A, et al. Risk factors for kidney stones in older women in the Southern United States. Am J Med Sci 2001;322:12-18.

- Borghi L, Schianchi T, Meschi T, et al. Comparison of two diets for the prevention of recurrent stones in idiopathic hypercalciuria. N Engl J Med 2002;346:77-84.

- Davies KM, Heaney RP, Recker RR, Lappe JM, Barger-Lux MJ, Rafferty K, Hinders S. Calcium intake and body weight. J. Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:4635-8.

- Heaney RP. Normalizing calcium intake: projected population effects for body weight. J Nutr 2003;133:268S-70S.

- Parikh SJ, Yanovski JA. Calcium intake and adiposity. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;77:281-7.

- Zemel MB. Regulation of adiposity and obesity risk by dietary calcium: mechanisms and implications. J Am Coll Nutr 2002;21:146S-51S.

- Jacobsen R, Lorenzen JK, Toubro S, Krog-Mikkelsen I, Astrup A. Effect of short-term high dietary calcium intake on 24-h energy expenditure, fat oxidation, and fecal fat excretion. Int J Obes 2005;29:292-301.

- Heaney RP. Calcium and weight: clinical studies. J Am Coll Nutr 2002;21:152S-5S.

- Shi H, DiRienzo DD, Zemel MB. Effects of dietary calcium on adipocyte lipid metabolism and body weight regulation in energy-restricted aP2-agouti transgenic mice. FASEB J 2001;15:291-3.

- Zemel MB, Shi H, Greer B, DiRienzo D, Zemel P. Regulation of adiposity by dietary calcium. FASEB J 2000;14:1132-8.

- Zemel MB, Thompson W, Milstead A, Morris K, Campbell P. Calcium and dairy acceleration of weight and fat loss during energy restriction in obese adults. Obes Res 2004;12:582-90.

- Zemel MB, Richards J, Mathis S, Milstead A, Gebhardt L, Silva E. Dairy augmentation of total and central fat loss in obese subjects. Int J Obes 2005;29:391-7.(a)

- Zemel MB, Richards J, Milstead A, Campbell P. Effects of calcium and dairy loss on body composition and weight loss in African-American adults. Obes Res 2005;13:1-8. (b)

- Barr SI. Increased dairy product or calcium intake: is body weight or composition affected in humans? J Nutr 2003;133:245S-8S.

- Gunther CW, Legowski PA, Lyle RM, McCabe GP, Eagan MS, Peacock M, Teegarden D. Dairy products do not lead to alterations in body weight or fat mass in young women in a 1-y intervention. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:751-6.

- Shapses SA, Heshka S, Heymsfield SB. Effect of calcium supplementation on weight and fat loss in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:632-7.

- Reid IR, Horne A, Mason B, Ames R, Bava U, Gamble GD. Effects of calcium supplementation on body weight and blood pressure in normal older women: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:3824-9.

- Sakhaee K, Maalouf NM. Editorial: dietary calcium, obesity and hypertension—the end of the road? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:4411-3.

- Gallagher JC, Goldgar D, Moy A. Total bone calcium in women: Effect of age and menopause status. J Bone Min Res 1987;2:491-96.

- Breslau NA. Calcium, estrogen, and progestin in the treatment of osteoporosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1994;20:691-716.

- Gallagher JC, Riggs BL, Deluca HF. Effect of estrogen on calcium absorption and serum vitamin D metabolites in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1980;51:1359-64.

- Daniels CE. Estrogen therapy for osteoporosis prevention in postmenopausal women. Pharmacy Update-NIH 2001;March/April.

- Dawson-Hughes B, Dallal GE, Krall EA, Sadowski L, Sahyoun N, Tannenbaum S. A controlled trial of the effect of calcium supplementation on bone density in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med 1990;323:878-83.

- Elders PJ, Lips P, Netelenbos JC, et al. Long-term effect of calcium supplementation on bone loss in perimenopausal women. J Bone Min Res 1994;9:963-70.

- Menopausal hormone therapy: Summary of a scientific workshop. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:361-364.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Questions and answers on hormone therapy. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Web site response to the WHI study results on estrogen and progestin hormone therapy. 2002.

- The North American Menopause Society. Position Statement: Role of progestrogen in hormone therapy for postmenopausal women: position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2003;10:113-132.

- American College of Sports Medicine. Menstrual cycle dysfunction. Current comment from the American College of Sports Medicine, October 2000.

- Abrams SA, Silber TJ, Esteban NV, et al. Mineral balance and bone turnover in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Pediatr 1993;123:326-331.

- Drinkwater B, Bruemner B, Chesnut C. Menstrual history as a determinant of current bone density in young athletes. JAMA 1990;263:545-48.

- Marcus R, Cann C, Madvig P, et al. Menstrual function and bone mass in elite women distance runners: Endocrine and metabolic features. Ann Intern Med 1985;102:158-63.

- Nattiv A. Stress fractures and bone health in track and field athletes. J Sci Med Sport 2000;3:268-79.

- Subcommittee on Body Composition and Nutrition and Health of Military Women, Committee on Military Nutrition Research, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Reducing Stress Fracture in Physically Active Military Women. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1998.

- Johnson AO, Semenya JG, Buchowski MS, Enwonwu CO, Scrimshaw NS. Correlation of lactose maldigestion, lactose intolerance, and milk intolerance. Am J Clin Nutr 1993;57:399-401.

- Nose O, Iida Y, Kai H, Harada T, Ogawa M, Yabuuchi H. Breath hydrogen test for detecting lactose malabsorption in infants and children: Prevalence of lactose malabsorption in Japanese children and adults. Arch Dis Child 1979;54:436-40.

- Rao DR, Bello H, Warren AP, Brown GE. Prevalence of lactose maldigestion: Influence and interaction of age, race, and sex. Dig Dis Sci 1994;39:1519-24.

- Coffin B, Azpiroz F, Guarner F, Mlagelada JR. Selective gastric hypersensitivity and reflex hyporeactivity in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 1994;107:1345-51.

- Horowitz M, Wishart J, Mundy L, Nordin BEC. Lactose and calcium absorption in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Arch Intern Med 1987;147:534-36.

- Tremaine WJ, Newcomer AD, Riggs BL, McGill DB. Calcium absorption from milk in lactase-deficient and lactase-sufficient adults. Dig Dis Sci 1986;31:376-78.

- Suarez FL, Savaiano DA, Arbisi P, Levitt MD. Tolerance to the daily ingestion of two cups of milk by individuals claiming lactose intolerance. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65:1502-06.

- Suarez FL, Savaiano DA, Levitt MD. A comparison of symptoms after the consumption of milk or lactose-hydrolyzed milk by people with self-reported severe lactose intolerance. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1-4.

- Johnson AO, Semenya JG, Buchowski MS, Enwonwu CO, Scrimshaw NS. Adaptation of lactose maldigester to continued milk intakes. Am J Clin Nutr 1993;58:879-81.

- Hertzler SR, Huynh B, Savaiano DA. How much lactose is "low lactose". J Am Diet Assoc 1996;96:243-46.

- Hertzler SR, Savaiano DA. Colonic adaptation to daily lactose feeding in lactose maldigesters reduces lactose intolerance. Am J Clin Nutr 1996;64:1232-36.

- Hertzler SR, Savaiano DA, Levitt MD. Fecal hydrogen production and consumption measurements: Response to daily lactose ingestion by lactose maldigesters. Dig Dis Sci 1997;42:348-53.

- Martini MC, Savaiano DA. Reduced intolerance symptoms from lactose consumed during a meal. Am J Clin Nutr 1988;47:57-60.

- Pribila BA, Hertzler SR, Martin BR, Weaver CM, Savaiano DA. Improved lactose digestion and intolerance among African-American adolescent girls fed a dairy-rich diet. J Am Diet Assoc 2000;100:524-528.

- Marsh AG, Sanchez TV, Midkelsen O, Keiser J, Mayor G. Cortical bone density of adult lacto-ovo-vegetarian and omnivorous women. J Am Diet Assoc 1980;76:148-51.

- Reed JA, Anderson JJ, Tylavsky FA, Gallagher JCJ. Comparative changes in radial-bone density of elderly female lacto-ovo-vegetarians and omnivores. Am J Clin Nutr 1994;59:1197S-1202S.

- Janelle KC, Barr SI. Nutrient intakes and eating behavior scores of vegetarian and non-vegetarian women. J Am Diet Assoc 1995;95:180-86.

- Burckhardt P, Dawson-Hughes B, Heaney RP. Nutritional aspects of osteoporosis. Academic Press 2001.

- Spencer H, Menczel J, Lewin I, Samachson J. Effect of high phosphorus intake on calcium and phosphorus metabolism in man. J Nutr 1965;86:125-32.

- Schiller L, Santa Ana C, Sheikh M, Emmett M, Fordtran J. Effect of the time of administration of calcium acetate on phosphorus binding. N Engl J Med 1989;320:1110-13.

- Hallberg L, Rossander-Hulten L, Brune M, Gleerup A. Calcium and iron absorption: Mechanism of action and nutritional importance. Eur J Clin Nutr 1992;46:317-27.

- Clarkson EM, Warren RL, McDonald SJ, de Wardener HE. The effect of a high intake of calcium on magnesium metabolism in normal subjects and patients with chronic renal failure. Clin Sci 1967;32:11-18.

- Shannon MT, Wilson BA, Stang CL. Health Professionals Drug Guide. Stamford, CT: Appleton and Lange, 2000.

- Jellin JM, Gregory P, Batz F, Hitchens K. Pharmacist's Letter/Prescriber's Letter Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. 3rd edition ed. Stockton, CA: Therapeutic Research Facility, 2000.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Home and Garden Bulletin No. 232 2000;Fifth Edition.

- Nutrition Business Journal. NBJ's supplement business report 2003. US consumer sales in $mil. San Diego, 2002:6.22.

- Andon MB, Peacock M, Kanerva RL, De Castro JAS. Calcium absorption from apple and orange juice fortified with calcium citrate malate (CCM). J Am Coll Nutr 1996;15:313-16.

- Heaney RP, Saville PD, Recker RR. Calcium absorption as a function of calcium intake. J Lab Clin Med 1975;85:881-90.

- Heaney RP, Recker RR, Hinders SM. Variability of calcium absorption. Am J Clin Nutr 1988;47:262-64.

- Levenson D, Bockman R. A review of calcium preparations. Nutr Rev 1994;52:221-32.

|

Reasonable care has been taken in preparing this document and the information provided herein is believed to be accurate. However, this information is not intended to constitute an "authoritative statement" under Food and Drug Administration rules and regulations. |

The mission of the Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS) is to strengthen knowledge and understanding of dietary supplements by evaluating scientific information, stimulating and supporting research, disseminating research results, and educating the public to foster an enhanced quality of life and health for the U.S. population. |

Health professionals and consumers need credible information to make thoughtful decisions about eating a healthful diet and using vitamin and mineral supplements. To help guide those decisions, registered dietitians at the NIH Clinical Center developed a series of Fact Sheets in conjunction with ODS. These Fact Sheets provide responsible information about the role of vitamins and minerals in health and disease. Each Fact Sheet in this series received extensive review by recognized experts from the academic and research communities.

The information is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice. It is important to seek the advice of a physician about any medical condition or symptom. It is also important to seek the advice of a physician, registered dietitian, pharmacist, or other qualified health professional about the appropriateness of taking dietary supplements and their potential interactions with medications.

|

Steven Abrams, M.D., Baylor College of Medicine

Bess Dawson-Hughes, M.D., USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University

Robert Heaney, M.D., Creighton University

Elizabeth Krall, Ph.D., M.P.H., Boston University

James M. Shikany, Dr. PH, University of Alabama at Birmingham

Dennis Savaiano, Ph.D, Purdue University

Paul Thomas, Ed.D., RD, The Dietary Supplement, LLC, Rockville, Maryland

Connie Weaver, Ph.D., Purdue University

|

|