1. The Stem Cell

What Is a Stem Cell?

A stem cell is a cell that has the ability to divide (self replicate) for indefinite periods—often throughout the life of the organism. Under the right conditions, or given the right signals, stem cells can give rise (differentiate) to the many different cell types that make up the organism. That is, stem cells have the potential to develop into mature cells that have characteristic shapes and specialized functions, such as heart cells, skin cells, or nerve cells.

The Differentiation Potential of Stem Cells: Basic Concepts and Definitions

Many of the terms used to define stem cells depend on the behavior of the cells in the intact organism (in vivo), under specific laboratory conditions (in vitro), or after transplantation in vivo, often to a tissue that is different from the one from which the stem cells were derived.

For example, the fertilized egg is said to be totipotent—from the Latin totus, meaning entire—because it has the potential to generate all the cells and tissues that make up an embryo and that support its development in utero. The fertilized egg divides and differentiates until it produces a mature organism. Adult mammals, including humans, consist of more than 200 kinds of cells. These include nerve cells (neurons), muscle cells (myocytes), skin (epithelial) cells, blood cells (erythrocytes, monocytes, lymphocytes, etc.), bone cells (osteocytes), and cartilage cells (chondrocytes). Other cells, which are essential for embryonic development but are not incorporated into the body of the embryo, include the extraembryonic tissues, placenta, and umbilical cord. All of these cells are generated from a single, totipotent cell—the zygote, or fertilized egg.

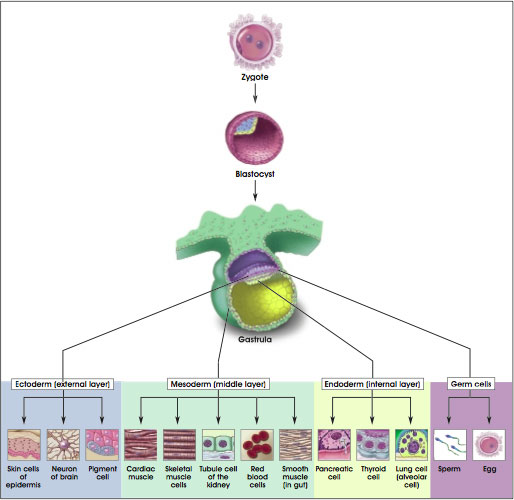

Most scientists use the term pluripotent to describe stem cells that can give rise to cells derived from all three embryonic germ layers—mesoderm, endoderm, and ectoderm. These three germ layers are the embryonic source of all cells of the body (see Figure 1.1. Differentiation of Human Tissues). All of the many different kinds of specialized cells that make up the body are derived from one of these germ layers (see Table 1.1. Embryonic Germ Layers From Which Differentiated Tissues Develop). "Pluri"—derived from the Latin plures—means several or many. Thus, pluripotent cells have the potential to give rise to any type of cell, a property observed in the natural course of embryonic development and under certain laboratory conditions.

Unipotent stem cell, a term that is usually applied to a cell in adult organisms, means that the cells in question are capable of differentiating along only one lineage. "Uni" is derived from the Latin word unus, which means one. Also, it may be that the adult stem cells in many differentiated, undamaged tissues are typically unipotent and give rise to just one cell type under normal conditions. This process would allow for a steady state of self-renewal for the tissue. However, if the tissue becomes damaged and the replacement of multiple cell types is required, pluripotent stem cells may become activated to repair the damage [2].

The embryonic stem cell is defined by its origin—that is from one of the earliest stages of the development of the embryo, called the blastocyst. Specifically, embryonic stem cells are derived from the inner cell mass of the blastocyst at a stage before it would implant in the uterine wall. The embryonic stem cell can self-replicate and is pluripotent—it can give rise to cells derived from all three germ layers.

The adult stem cell is an undifferentiated (unspecialized) cell that is found in a differentiated (specialized) tissue; it can renew itself and become specialized to yield all of the specialized cell types of the tissue from which it originated. Adult stem cells are capable of self-renewal for the lifetime of the organism. Sources of adult stem cells have been found in the bone marrow, blood stream, cornea and retina of the eye, the dental pulp of the tooth, liver, skin, gastrointestinal tract, and pancreas. Unlike embryonic stem cells, at this point in time, there are no isolated adult stem cells that are capable of forming all cells of the body. That is, there is no evidence, at this time, of an adult stem cell that is pluripotent.

Figure 1.1. Differentiation of Human Tissues.

(© 2001 Terese Winslow, Caitlin Duckwall)

Table 1.1. Embryonic Germ Layers From Which Differentiated Tissues Develop [1]

| Embryonic Germ Layer |

Differentiated Tissue |

| Endoderm |

Thymus

Thyroid, parathyroid glands

Larynx, trachea, lung

Urinary bladder, vagina, urethra

Gastrointestinal (GI) organs (liver, pancreas)

Lining of the GI tract

Lining of the respiratory tract |

| Mesoderm |

Bone marrow (blood)

Adrenal cortex

Lymphatic tissue

Skeletal, smooth, and cardiac muscle

Connective tissues (including bone, cartilage)

Urogenital system

Heart and blood vessels (vascular system) |

| Ectoderm |

Skin

Neural tissue (neuroectoderm)

Adrenal medulla

Pituitary gland

Connective tissue of the head and face

Eyes, ears |

References

- Chandross, K.J. and Mezey, E. (2001). Plasticity of adult bone marrow stem cells. Mattson, M.P. and Van Zant, G. eds. (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press).

- Slack, J.M. (2000). Stem cells in epithelial tissues. Science. 287, 1431–1433.

Executive Summary | Table of Contents | Chapter 2

Executive Summary | Table of Contents | Chapter 2

Historical content: June 17, 2001