The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP) and its legal offspring, the Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, developed a systematic attack against the doctrine of "separate

but equal." The campaign started at the graduate and professional

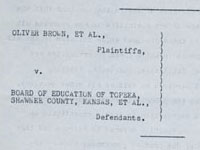

educational levels. The attack culminated in five separate cases

gathered together under the name of one of them--Oliver Brown

v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

Aware of the gravity of the issue and concerned with the possible

political and social repercussions, the U.S. Supreme Court heard

the case argued on three separate occasions in as many years. The

Court weighed carefully considerations involving adherence to legal

precedent, social-science findings on the negative effects of segregation,

and the marked inferiority of the schools that African Americans

were forced to attend.

The Supreme Court announced its unanimous decision on May 17,

1954. It held that school segregation violated the Equal Protection

and Due Process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. The following

year the Court ordered desegregation "with all deliberate speed."

The Library of Congress

does not have permission to show this image online.

Notebook recording data concerning the Doll

Test, 1940-1941. Kenneth B. Clark Papers,

Manuscript Division (61) |

Kenneth B. Clark's "Doll Test" Notebook

During the 1940s, psychologists Kenneth

Bancroft Clark and his wife, Mamie Phipps Clark designed

a test to study the psychological effects of segregation

on black children. In 1950 Kenneth Clark wrote a paper for

the White House Mid-Century Conference on Children and Youth

summarizing this research and related work that attracted

the attention

of Robert Carter of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. Carter

believed that Clark's findings could be effectively used

in court to show that segregation damaged the personality

development of black children. On Carter's recommendation,

the NAACP Legal Defense Fund engaged Clark to provide expert

social science testimony in the Briggs, Davis,

and Delaware cases. Clark also co-authored a summation of

the social science testimony delivered during the trials

that was endorsed by thirty-five leading social scientists.

The Supreme Court specifically cited Clark's 1950 paper in

the Brown decision.

|

Dr. Kenneth Clark Conducting the "Doll Test"

In the "doll test," psychologists Kenneth

and Mamie Clark used four plastic, diaper-clad dolls, identical

except for color. They showed the dolls to black children

between the ages of three and seven and asked them questions

to determine racial perception and preference. Almost all

of the children readily identified the race of the dolls.

However, when asked which they preferred, the majority selected

the white doll and attributed positive characteristics to

it. The Clarks also gave the children outline drawings of

a boy and girl and asked them to color the figures the same

color as themselves. Many of the children with dark complexions

colored the figures with a white or yellow crayon. The Clarks

concluded that "prejudice, discrimination, and segregation" caused

black children to develop a sense of inferiority and self-hatred.

This photograph was taken by Gordon Parks for a 1947 issue

of Ebony magazine.

|

The Library of Congress

does not have permission to show this image online.

Gordon Parks, photographer. Dr. Kenneth

Clark conducting the "Doll Test" with a young male child,

1947.

Gelatin silver print.

Prints and Photographs Division (62) |

Marjory Collins.

Reading lesson in African American elementary

school in Washington, D.C., 1942.

Gelatin silver print.

FSA-OWI Photograph Collection,

Prints and Photographs Division (57C)

|

Reading Lesson in Washington, D.C.

As the nation's capital became more and

more populated by blacks in the first half of the twentieth

century, the schools in District of Columbia became more

segregated. During World War II, there was no new construction

of schools and the few that existed were extremely overcrowded.

After the war, new construction started but did not meet

the needs of the District's populace. Many black students

were attending schools in shifts while many of the white

schools sat nearly empty. This condition eventually led to

the Bolling v. Sharpe case, one of the five included

in the Brown v. Board of Education decision. |

Kenneth B. Clark's "Doll Test" Data Sheet

The Clarks used printed data sheets to

record the children's responses during the "doll test," as

well as general observations. This data sheet lists the nine

questions that were routinely asked. The letters "B" and "W" denote "black" and "white." The

abbreviations "LB" and "DB" denote "light brown" and "dark

brown" complexions. The data reveals that Mark A., a black

boy age four with a dark brown complexion, prefers the white

doll and selects the white doll as the one that looks like

him.

|

The Library of Congress

does not have permission to show this image online.

Sample Doll Test data sheet, n.d. Kenneth

B. Clark Papers,

Manuscript Division (64) |

The Library of Congress

does not have permission to show this image online.

Testimony of Expert Witnesses at Trial

of Clarendon County School Case Direct Examination by Robert

L. Carter, May 29, 1951. Transcript.

NAACP Records,

Manuscript Division (57) |

Briggs v. Elliott (South Carolina)

In 1949, the state NAACP in South Carolina

sought twenty local residents in Clarendon County to sign

a petition for equal education. The petition turned into

a lawsuit and first name on the list was Harry Briggs. In

preparation for the Briggs case, attorney Robert

Carter returned to Columbia University to confer with Psychologist

Otto Klineberg, who was known for his research on black students'

IQ scores. He sought Klineberg's advice on the use of social

science testimony in the pending trial to show the psychological

damage segregation caused in black children. Klineberg recommended

Kenneth Clark. Clark became the Legal Defense Fund's principal

expert witness. He also agreed to assist the Legal Defense

Fund 's lawyers in the preparation of briefs and recruit

other prominent social scientists to testify. This document

records the depositions of two expert witnesses who participated

in Briggs v. Elliott: David Krech, a social

psychology professor at the University of California; and

Helen Trager, a lecturer at Vassar College. |

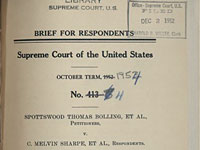

Bolling v. Sharpe, (Washington D.C.)

Spottswood Thomas Bolling v. C. Melvin

Sharpe, was one of the five school desegregation cases

that comprised Brown. Because the District of

Columbia was not a state but federal territory, the Fourteenth

Amendment arguments used in the other cases did not apply.

Therefore, the lawyers argued for "Due Process Clause" of

the Fifth Amendment, which guaranteed equal protection

of the law. The Consolidated Parents Group initiated a

boycott of the black High School in Washington. D.C., which

was overcrowded and dilapidated. In 1948, Charles H. Houston

was hired to represent them in a law suit to make black

schools more equal to white schools when Houston's health

began to fail. He recommended James Nabrit as his replacement.

Nabrit was joined by fellow attorney, George E. C. Hayes

in presenting arguments for the District of Columbia case.

|

U. S. Supreme Court Records

and Briefs, 1954 Term.

Supreme Court Records and Briefs,

Law Library (57B)

|

Brief of the Attorneys

for the Plaintiffs (Charles

E. Bledsoe, Charles Scott, Robert L. Carter, Jack Greenberg,

and Thurgood Marshall) in the case of Oliver Brown,

. . .delivered in the United States Court for the District

of Kansas,

June 1951.

Page 2

NAACP Records,

Manuscript Division (54)

Courtesy of the NAACP

|

Brief of the Attorneys for the Plaintiffs in Brown

In June 1950, shortly after the Sweatt, McLaurin,

and Henderson victories, Thurgood Marshall convened

a conference of the NAACP's board of directors and affiliated

attorneys to determine the next step in the legal campaign.

After several days of debate, Marshall decided to shift the

focus from the inequality of separate black schools to a

full assault on segregation. The NAACP immediately instituted

lawsuits concerning segregated public schools in Southern

and border states. Brown v. Board of Education was

filed in the U.S. District Court in Topeka, Kansas, in February

1951 and litigated concurrently with Briggs v. Elliot in

South Carolina. Oliver Brown, one of thirteen plaintiffs,

had agreed to participate on behalf of his seven-year-old

daughter Linda, who had to walk six blocks to board a school

bus that drove her to the all-black Monroe School a mile

away. |

Finding of Fact for the Case of Oliver Brown

On June 25, 1951, Robert Carter and Jack

Greenberg argued the Brown case before a three judge

panel in district court in Kansas. They were assisted by

local NAACP attorneys Charles Bledsoe and brothers John and

Charles Scott. As in Briggs, the testimony of social

scientists was central to the case. The Court found "no willful,

intentional or substantial discrimination" in Topeka's schools.

However, presiding Judge Walter A. Huxman appended nine "Findings

of Fact" to the opinion. Fact VIII endorsed the psychological

premise that segregation had a detrimental effect on black

children. This was the windfall the NAACP needed to appeal

the case to the Supreme Court. Briggs and Brown were

the first cases to reach the Court; three others followed.

The Court decided to bundle all five cases and scheduled

a hearing for December 9, 1952.

|

Opinion and Finding of

Fact for the case of Oliver Brown, et al. v. Board of

Education Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas, et al. Delivered

in the United States Court for the District of Kansas,

1951.

NAACP Records,

Manuscript Division (55)

Courtesy of the NAACP

|

The Library of Congress

does not have permission to show this image online

Trial Memorandum from Jack Greenberg concerning

the Wilmington school case, October 11, 1951.

NAACP Records,

Manuscript Division (58) |

Gebhart v. Belton; Gebhart v. Bulah (Delaware)

In 1950 Louis Redding filed a lawsuit

on behalf of Sarah Bulah to admit her daughter Shirley to

a nearby white elementary school, after the Delaware Board

of Education refused to allow her to board an all-white school

bus that drove pass their home. In 1951, Redding filed a

second suit on behalf of Ethel Belton and nine other plaintiffs,

whose children were barred from attending the all-white high

school in their community. That fall, Thurgood Marshall sent

Jack Greenberg to Wilmington to work with Redding on the

litigation. Greenberg drafted this meticulous trial memorandum

the week before the hearing. In it he provides a schedule

of witnesses, instructions on deposing the witnesses, and

the questions to be posed. Among the witnesses listed are

psychologists Kenneth Clark and Otto Klineberg. |

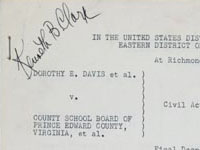

A Court Rules: Equalization, Not Integration

Spurred by a student strike, blacks in

Prince Edward County, Virginia, called a lower federal court's

attention to the demonstrably unequal facilities in the county's

segregated high schools. As this "Final Decree" in Davis

v. County School Board shows, they convinced the U.S.

District Court that facilities for blacks were "not substantially

equal" to those for whites. The Court ordered the two systems

to be made equal. However, it did not abolish segregation.

Therefore, the plaintiffs appealed, and the Supreme Court

heard their case along with Brown v. Board. |

United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia. Final Decree,

[1952].

Typed memorandum.

Kenneth Clark Papers,

Manuscript Division (59)

|

Brief for Appellants in

the cases of Brown v. Board of Education: Oliver Brown,

et al. v. Board of Education, Kansas et al.; . . . in

the United States Supreme Court-October Term, 1953.

Washington: GPO, 1953.

Pamphlet.

NAACP Records,

Manuscript Division (73)

Courtesy of the NAACP

|

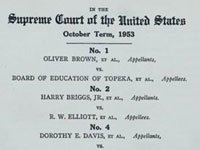

Brief for Appellants, Brown v. Board, 1953

The Supreme Court did not render a judgement

after the initial oral arguments in Brown v.

Board. Instead, the Court submitted a list of five questions

for counsel to discuss at a rehearing that convened on December

7, 1953. The questions pertained to the history of the Fourteenth

Amendment and the relation between the views of the Amendment

framers' intent to "abolish segregation in public schools." The

questions also addressed what remedies to be used in the

event the Court ruled segregation in public schools unconstitutional.

After assessing the questions, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund

assembled a team of experts, including John A. Davis, a professor

of political science at Lincoln University, Mabel Smythe,

an economist, and psychologist Kenneth Clark, and scholars

John Hope Franklin, C. Vann Woodward, and Horace Mann Bond,

to conduct research during the summer. |

Eisenhower and Davis

As President (1953-1961), Dwight David

Eisenhower took decisive action to enforce court rulings

eliminating racial segregation. He would not, however, endorse

the Brown decision or condemn segregation as morally

wrong. John W. Davis, who had been the Democratic Party's

unsuccessful candidate for president in 1924, was the lead

counsel in the South's effort to uphold the Plessy v.

Ferguson doctrine of "separate but equal" in arguments

before the Supreme Court in 1953. The two men are shown meeting

in New York in October 1952, shortly before Davis would endorse

Eisenhower for president. Thurgood Marshall in later years

would say of Davis, "He was a good man . . . who believed

segregation was a good thing."

|

Ike with John W. Davis

at the Herald Trib Forum 10/21, 1952.

Photograph.

New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection,

Prints and Photographs Division (73A)

|

Waiting for courtroom seats,

1953.

Gelatin silver print.

New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection,

Prints and Photographs Division (74)

Digital ID# cph 3c13498

|

Waiting for Courtroom Seats

This photograph shows interested members

of the public waiting in line outside the Supreme Court for

a chance to obtain one of the 50 seats allotted to hear the

second round of arguments in the landmark Brown v. Board

of Education case. The case involved four states (Kansas,

Virginia, Delaware and South Carolina) and the District of

Columbia. Among an impressive array of legal representation

for the plaintiffs was Thurgood Marshall serving as chief

council for the NAACP. The opposing side was led by John

W. Davis, one time Democratic presidential candidate and

expert on constitutional law. |

Three Lawyers Confer at the Supreme Court

In preparation for the Brown court

case the three lead lawyers gathered to discuss their final

strategy. Pictured (left to right)are Harold

P. Boulware, (Briggs case), Thurgood Marshall, (Briggs case),

and Spottswood W. Robinson III (Davis case). The

lawyers said that the Brown case hoped to end the "separate

but equal" doctrine of the earlier Plessy decision

and make it illegal to continue segregation in public schools. |

Three lawyers confer at the

Supreme Court, 1953.

Gelatin silver print.

New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection,

Prints and Photographs Division (98)

|

U. S. Supreme Court Justices,

1953.

Photograph.

New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection,

Prints and Photographs Division (102)

|

The Warren Court

Pictured in this photograph are nine

members of the Supreme Court that decided Brown v. Board

of Education. Seated in the front row (from left)

Felix Frankfurter, Hugo Black, Earl Warren, Stanley Reed,

and William O. Douglas. In the back row are Tom Clark, Robert

H. Jackson, Harold Burton, Sherman Minton. The photograph

was taken late in 1953, after President Dwight D. Eisenhower

had nominated Warren to the Court, but before the U.S. Senate

had confirmed him as Chief Justice. |

Brown Attorneys After the Decision

Three lawyers, Thurgood Marshall (center),

chief counsel for the NAACP's Legal Defense Fund and lead

attorney on the Briggs case, with George E. C. Hayes

(left) and James M. Nabrit (right), attorneys

for Bolling case, standing on the steps of the Supreme

Court congratulating each other after the court ruling that

segregation was unconstitutional. |

George E. C. Hayes, Thurgood

Marshall, and James M. Nabrit congratulating each other,

1954.

Gelatin silver print.

New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection,

Prints and Photographs Division (99)

[Dig ID # cph 3c11236]

|

The Russell

Daily News (Russell, Kansas),

Monday, May 17, 1954.

Enlarged version

Historic Events Newspaper Collection,

Serial and Government Publications Division (84)

|

"Segregation in Schools is Outlawed"

The case that gave the Brown v. Board

of Education decision its name originated in a Federal

District Court in Topeka, Kansas. The Russell Daily

News, serving the city and county of Russell, Kansas,

announced the decision with a banner headline and two front

page stories. On the day of the decision, this evening

newspaper carried United Press reports from Washington,

D.C., and from Topeka, along with the ruling and the Kansas

Attorney General's statement of intention to comply. |

Humiliation and Inferiority

William T. Coleman assisted Thurgood

Marshall with the planning and execution of the Brown litigation.

Member of the NAACP Legal Committee, Coleman's stellar academic

record at the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard Law

School paved his way to the Supreme Court, where he became

the first African American clerk in 1948. Coleman wrote this

memorandum for Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter in 1949.

Agreeing with Coleman's contention that segregation was unconstitutional

because it was an humiliating sign of inferiority, Frankfurter

commented: "That it is such has been candidly acknowledged

by numerous accounts & adjudications in those States

where segregation is enforced. Only self conscious superiority

or inability to slip into the other fellow's skin can fail

to appreciate that." |

The Library of Congress

does not have permission to show this image online.

William Coleman to Felix Frankfurter, August

5, 1949.

Typed memorandum with handwritten notes.

Felix Frankfurter Papers,

Manuscript Division (48) |

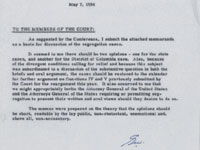

Earl Warren to members of

the Court, May 7, 1954.

Typed memorandum.

Earl Warren Papers,

Manuscript Division (80)

|

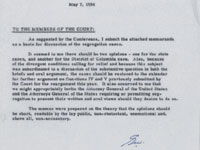

Warren Works For Unanimity

Realizing that overturning school segregation

in the South might entail a degree of social upheaval, Chief

Justice Warren carefully engineered a unanimous vote, one

without dissents or separate concurring opinions. Assigning

the two opinions--one for state schools, one for federal--to

himself, he circulated two draft memoranda with opinions

to his colleagues. He proposed to put off the tricky question

of implementation until later. He also set forth his idea

that "opinions should be short, readable by the lay public,

non-rhetorical, unemotional and, above all, non-accusatory." |

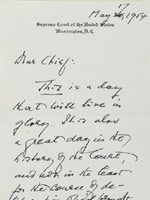

"A Beautiful Job"

Early in May 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren circulated

draft opinions for the school desegregation cases to his

colleagues on the Court. Associate Justice William O. Douglas

responded enthusiastically in this handwritten note: "I

do not think I would change a single word in the memoranda

you gave me this morning. The two draft opinions meet my

idea exactly. You have done a beautiful job."

|

William Douglas to Earl

Warren, May 11, 1954.

Holograph letter.

Earl Warren Papers,

Manuscript Division (81A)

|

Harold H. Burton to Earl

Warren, May 17, 1954.

Holograph letter.

Earl Warren Papers,

Manuscript Division (82)

|

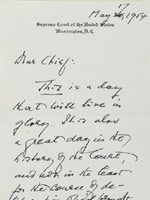

"A Great Day for America"

Associate Justice Harold H. Burton sent this note to Chief

Justice Earl Warren on the day that the Supreme Court's

decision in Brown v. Board was announced. He said, "Today

I believe has been a great day for America and the Court.

. . . I cherish the privilege of sharing in this." In a

tribute to Warren's judicial statesmanship, Burton added, "To

you goes the credit for the character of the opinions which

produced the all important unanimity. Congratulations."

|

Frankfurter's Congratulations to Warren

Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter, who had worked to

achieve a definitive repudiation of segregation by the

Supreme Court, sent this note to Chief Justice Warren on

the day that the decision in Brown v. Board was

publicly announced--a day that Frankfurter said would "live

in glory." Frankfurter added that the Court's role was

also distinguished by "the course of deliberation which

brought about the result."

|

Felix Frankfurter to Earl

Warren, May 17, 1954.

Holograph letter.

Earl Warren Papers,

Manuscript Division (82B)

|

Waiting for courtroom seats,

1953.

Gelatin silver print.

New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection,

Prints and Photographs Division (74)

Digital ID# cph 3c13498

|

Waiting for Courtroom Seats

This photograph shows interested members of the public

waiting in line outside the Supreme Court for a chance

to obtain one of the 50 seats allotted to hear the second

round of arguments in the landmark Brown v. Board of

Education case. The case involved four states (Kansas,

Virginia, Delaware and South Carolina) and the District

of Columbia. Among an impressive array of legal representation

for the plaintiffs was Thurgood Marshall serving as chief

council for the NAACP. The opposing side was led by John

W. Davis, one time Democratic presidential candidate and

expert on constitutional law.

|

Warren's Reading Copy of the Brown Opinion,

1954

Chief Justice Earl Warren's reading copy

of Brown is annotated in his hand. Warren announced

the opinion in the names of each justice, an unprecedented

occurrence. The drama was heightened by the widespread prediction

that the Court would be divided on the issue. Warren reminded

himself to emphasize the decision's unanimity with a marginal

notation, "unanimously," which departed from the printed

reading copy to declare, "Therefore, we unanimously hold.

. . ." In his memoirs, Warren recalled the moment with genuine

warmth. "When the word 'unanimously' was spoken, a wave of

emotion swept the room; no words or intentional movement,

yet a distinct emotional manifestation that defies description." "Unanimously" was

not incorporated into the published version of the opinion,

and thus exists only in this manuscript. |

Earl Warren's reading copy

of Brown opinion,

May 17, 1954.

Earl Warren Papers,

Manuscript Division (83)

|

Mrs. Nettie Hunt and daughter

Nikie on the steps of the Supreme Court, 1954.

Gelatin silver print.

New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection,

Prints and Photographs Division (97)

Digital ID # cph 3c27042

|

Celebration of the Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court's decision on the Brown v. Board of

Education case in 1954 marked a culmination in a plan

the NAACP had put into action more than forty years earlier--the

end to racial inequality. African American parents throughout

the country like Mrs. Hunt, shown here, explained to their

children why this was an important moment in history.

|

Segregation Ruling Explained to the Press

Chief counsel for the NAACP Thurgood

Marshall spoke to the press in New York City on May 31 after

the Supreme Court decreed an end to public school segregation

as soon as feasible. At the news conference in New York City,

Marshall told reporters ". . .the law had been made crystal

clear" and added, "Southerners are just as law abiding as

anyone else, once the law is made clear." He was speaking

after Brown II, the court's second opinion in the Brown case,

which ordered the implementation of the original ruling in

a "prompt and reasonable" start towards desegregation. |

Thurgood Marshall explains

segregation

ruling to the press, 1955.

Gelatin silver print.

New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection,

Prints and Photographs Division (104)

|

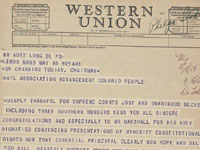

Anson Phelps Stokes to Channing

Tobias, Chairman of the NAACP, offering congratulations

on the NAACP's victory in Brown v. Board of Education.

Telegram.

NAACP Records,

Manuscript Division (96)

Courtesy of the NAACP

|

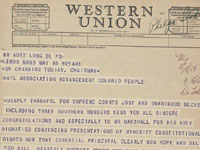

Congratulatory Telegram on Brown Decision

The NAACP's affiliation with the philanthropic

Stokes family began with J. G. Phelps Stokes, one of the

organization's founders. At the time of the Brown decision,

Anson Phelps Stokes was president of the Phelps-Stokes Fund,

a charitable trust that sponsored black schools and educational

projects. Stokes became familiar with the racial politics

of the South through his work with the Tuskegee Institute.

This telegram celebrates the consensus of the Southern justices

and urges the NAACP to "heartily support the court decision

postponing implementing orders so that these wonderful new[s]

gains may be safe guarded with minimum disturbances in a

difficult situation. . . ." |

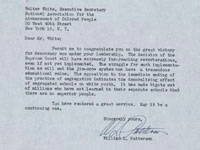

Congratulatory Letter on the Brown Decision

William Patterson was an attorney and

former Executive Secretary of the International Labor Defense

(ILD), an organization dedicated to protecting the rights

of racial minorities, political radicals, and the working

class. In 1931, the ILD competed with the NAACP for the right

to represent the "Scottsboro Boys," nine black men convicted

of raping two white women. The NAACP lost the bid because

it lacked a full-time legal staff spurring Walter White,

then head of the NAACP, to hire Charles H. Houston and set

up a legal department. In this letter Patterson, head of

the Civil Rights Congress, a leftist organization, attributes

opposition to the Brown decision to "the demoralizing

effect of segregated schools on white youth. It has made

bigots out of millions who have not learned in their separate

schools that there are no superior people." |

William L. Patterson, Executive

Secretary of the Civil Rights Congress, to Walter White

congratulating White on the NAACP's victory in Brown

v. Board of Education,

May 17, 1954.

Typed letter.

NAACP Records,

Manuscript Division (95)

Courtesy of the NAACP

|

The Library of Congress

does not have permission to show this image online

The Crisis magazine: A Record

of the Darker Races.

Volume 61, no. 6 (June-July, 1954).

General Collections (92) |

An African American Response

The multi-faceted African American response

to the decision was articulated throughout the black press

and in editorials published in official publications of national

black organizations. Founded in 1910, The Crisis magazine,

shown here, is the official organ of the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In response

to the decision, a special issue of The Crisis was

printed to include the complete text of the Supreme Court

decision, a history of the five school cases, excerpts from

the nation's press on segregation ruling, and the text of

the "Atlanta Declaration," the official NAACP response and

program of action for implementing the decision. |

Conferring at the Supreme Court

In 1929 Louis L. Redding, a graduate

of Brown University and Harvard Law School, became the first

African American attorney in Delaware--the only one for more

than twenty years. He devoted his practice to civil rights

law and served as the counsel for the NAACP Delaware branch.

In 1949 Redding won the landmark Parker case, which

resulted in the desegregation of the University of Delaware.

In1951, Redding and Greenberg tried two cases in Delaware's

Chancery Court: Bulah v. Gebhart and Belton

v. Gebhart, which respectively concerned elementary

school and high school. On April 1, 1952, Judge Collins Seitz

ordered the immediate admission of black students to Delaware's

white public schools, but the local state-run-school board

appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court. |

Louis L. Redding of Wilmington,

Delaware, and Thurgood Marshall, General Counsel for the

NAACP, conferring at the Supreme Court, during recess in

the Court's hearing on racial integration in public schools,

1955.

Gelatin silver print.

Visual Materials from the NAACP Records Photograph,

Prints and Photographs Division (111)

Courtesy of the NAACP

|

Felix Frankfurter's draft

decree in Brown II,

April 8, 1955.

Page 2

Typescript with emendations.

Felix Frankfurter Papers,

Manuscript Division (107)

|

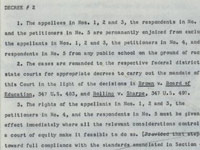

Frankfurter's Draft Decree in Brown II, 1955

After the Brown opinion was announced, the Court

heard additional arguments during the following term on the

decree for implementing the ruling. In a draft, prepared

by Felix Frankfurter, which Warren subsequently adopted,

Frankfurter inserted "with all deliberate speed" in place

of "forthwith," which Thurgood Marshall had suggested to

achieve an accelerated desegregation timetable. Frankfurter

wanted to anchor the decree in an established doctrine, and

his endorsement of it sought to advance a consensus held

by the entire court. The justices thought that the decree

should provide for flexible enforcement, appeal to established

principles, and suggest some basic ground rules for judges

of the lower courts. When it became clear that opponents

of desegregation were using the doctrine to delay and avoid

compliance with Brown, the Court began to express

reservations about the phrase. |

Topeka School Map

In response to requests from two Justices

during the oral arguments of the implementation phase of Brown

v. Board, Kansas Attorney General Harold Fatzer provided

the Court with this map of the Topeka public school districts

along with 1956 enrollment estimates by race. Although almost

all of the schools shown were either overwhelmingly white

or completely black, Fatzer argued that Topeka had not deliberately

gerrymandered the districts so as to concentrate black pupils

into a few districts. Also shown is a key to the map, representing

the placement of students in the districts. |

The Library of Congress

does not have permission to show this image online

Raymond F. Tilzey.

The Elementary School District Boundaries for the City of Topeka 1955- 1956.

Printed Map.

Earl Warren Papers,

Manuscript Division (109) |

|

The Library of Congress does not have permission

to show this image online

Ralph McGill to Earl Warren, June 1, 1955.

Typed letter.

Earl Warren Papers,

Manuscript Division (113A) |

Southern White Liberal Reaction

Many white Southern liberals welcomed

the moderate and incremental approach of the Brown implementation

decree. Ralph McGill, the influential editor of the Atlanta

Constitution, wrote in praise of the Court's decision

to have local school boards, in conjunction with Southern

court judges, formulate and execute desegregation orders.

Certain that "the problem of desegregation had to be solved

at the local level," he told Chief Justice Warren that the

Court's ruling was "one of the great statesman-like decisions

of all time," exceeding all previous decisions "in wisdom

and clarity." |

Adverse Reactions to Brown

Challenges to legal and social institutions

implicit in the Brown decision led to adverse reactions

in both Northern and Southern states. U.S. Solicitor General

Simon Sobeloff forwarded to Chief Justice Warren this letter

from an official of the New York chapter of the Sons of the

American Revolution. The official attributed the impetus

behind the Court's action to "the worldwide Communist conspiracy" and

claimed that the NAACP had been financed by "a Communist

front." |

The Library of Congress

does not have permission to show this image online

Lee Hagood to Simon Sobeloff, September

29, 1955.

Typed letter.

Earl Warren Papers,

Manuscript Division (116A) |

Time magazine,

September 19, 1955.

Cover.

General Collections (115)

Courtesy of Time-Life Pictures, Getty Images

|

Thurgood Marshall

After the U.S. Supreme Court's decision

on May 17, 1954, and May 31, 1955, desegregating schools,

Thurgood Marshall (1908-1994), was featured on the cover

of Time magazine, on September 19, 1955. Born in

Baltimore, Maryland, Marshall graduated with honors from

Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. His exclusion from the

University of Maryland's Law School due to racial discrimination,

marked a turning point in his life. As a result, he attended

the Howard University Law School, and graduated first in

his class in 1933. Early in his career he traveled throughout

the South and argued thirty-two cases before the Supreme

Court, winning twenty-nine. Charles H. Houston persuaded

him to leave private law practice and join the NAACP legal

staff in New York, where he remained from 1936 until 1961.

In 1939, Marshall became the first director of the NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. President Lyndon

B. Johnson appointed Marshall as Solicitor General in 1965

and nominated him to a seat on the United States Supreme

Court in 1967 from which he retired in 1991.

|

Barnard Elementary, Washington, D. C.

This image of an integrated classroom

in the previously all white Barnard Elementary School in

Washington, D.C., shows how the District's Board of Education

attempted to act quickly to carry out the Supreme Court decision

to integrate schools in the area. However, it did take longer

for the junior and senior high schools to integrate. |

Thomas J. O'Halloran.

School integration, Barnard School, Washington,

D.C., 1955.

Gelatin silver print.

U.S. News & World Report Magazine Collection,

Prints and Photographs Division (202)

|

|