Hell-Bent for Literature

September 12, 2008

Washington, DC

“…the Murmur, — ever, unceasingly, the great, crisp, serene Roar, — of a Mobility focus’d upon a just purpose.” – Thomas Pynchon, Mason & Dixon , p.502

Nobody attributes quotes anymore, and few enough people bother to quote at all. We’re-hearing a lot of speeches down the stretch of the election steeplechase these days, but too often a speaker will come out with something like, “A great writer once said…” or “A great poet once wrote…” Am I the only listener who hears these airy anonymities and wants to know who did the saying or the writing?

Thanks to Google I can usually find out, but this phenomenon strikes me as just one more example of literature’s creeping marginalization. It’s as if the quoters fear that citing Walter Lippman or Robert Frost at a political convention and the Pentagon Memorial dedication, respectively, would open them up to killing charges of elitism. When a rare convention speaker quoted Harriet Tubman by name — neatly reconciling her wary feminist and African American listeners at a stroke — it was a rare reminder of what a well-chosen quote can do.

Another thing a quote can do, of course, is give you a throat-clearing explanatory paragraph or two to play with before you get around to the meat, if any, of your message. The truth is, I’m quoting my old lodestar Pynchon for luck, because, for the next fortnight, I’m going to need it.

|

|

|

Kipen hits the road, striking terror into the hearts of nonreaders and pedestrians alike. NEA Photo. |

A little over three hours from now, I’m setting sail on a cross-country voyage into the heart of American reading. May regular readers of this blog forgive me for repeating that this road trip is all part of my work on something called The Big Read, a program that helps American cities and towns read great books old and new together. In so doing, townsfolk often discover for the first time not only the joys to be had from a good book but, better late than never, the names of their own neighbors. To see these twin goals realized time after time, in town after town, is the incomparable privilege of this job.

Since I left my old gig reviewing books for the San Francisco Chronicle, I’ve had exactly two ideas. One was this blog (http://www.nea.gov/bigreadblog), which seemed all cutting-edge and un-federal and state-of-the-art when we started it, and is now more or less standard operating procedure at even the stodgiest of institutions. The other was Rosie, a custom-wrapped cherry-red hybrid automobile that could hopscotch from city to city, enabling me to see the program firsthand, and maybe to pitch in with the odd keynote address.

While Rosie and I have made a couple of brief forays to nearby states since Ford donated her this year, today marks the first of what’s envisioned as a series of coast-to-coast trips to focus attention on The Big Read — not for attention’s own meager sake, but to drum up new applications for the initiative, and to lend a sense of occasion to Big Reads already going. Along the way I plan to sideswipe more than a dozen participating burgs, listen to some quintessentially American road reading — including but not limited to Leaves of Grass, Against the Day, and On the Road — and probably eat more road food than a man my age can safely risk.

Why do this? Why leave a comfortable, well-paying duck blind for the shooting of bad books to become some G-man, shilling for a quixotic government program bent on getting people to do what most of popular culture conspires around the clock to distract them from?

Because, in spite of myself, I believe in The Big Read. I’ve seen it work too often not to. I believe that reading makes you a deeper, fuller, more completely human being. I believe that reading good books, especially, can make you, for lack of a better word, a better person. I believe the latter in spite of copious personal experience to the contrary, since I’ve been reading all my life, and yet my co-workers, friends, loves and family will all attest that I could still use some serious work.

Before this turns into a particularly maudlin installment of “This I Believe” — and before I miss my first engagement tonight, kicking off Winston-Salem’s Big Read of Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 — I should give some thought to winding it up. But on my way out the door, spare me a minute to parse that Pynchon quote up top. I chose it because of its quintessentially Pynchonian use of the word “mobility” to mean a “ crowd of common folk,” as the lay Pynchon scholar Tim Ware calls (http://www.hyperarts.com/thomas-pynchon/).

I love this equation of democracy with mobility. There’s something about people in general and Americans in particular that wants motion — preferably locomotion of a vehicular variety, and from ocean to ocean.

This gets complicated lately, what with the high price and hellacious environmental hangover of internal combustion — which is why the NEA has made it our business to work with Ford to get the tiptoeing-est carbon footprint we could find. It wouldn’t do to get Americans reading while at the same time slowly asphyxiating them.

So, by the time you’re reading this, I’ll have embarked on the following itinerary:

9-12 Winston-Salem, NC, reading Fahrenheit 451

9-13 Roxboro, NC, reading The Grapes of Wrath

9-14 Douglasville, GA, reading To Kill a Mockingbird

9-15 Hattiesburg, MS, reading Their Eyes Were Watching God

9-16 Mesquite, TX, reading Fahrenheit 451

9-17 Austin, TX, outreach encouraging applications for the next Big Read

9-18 Corpus Christi, TX, reading Fahrenheit 451

9-19 El Paso, TX, reading Sun, Stone, and Shadows

9-20 Pleasanton, CA, reading The Great Gatsby AND Rohnert Park, CA reading To Kill a Mockingbird

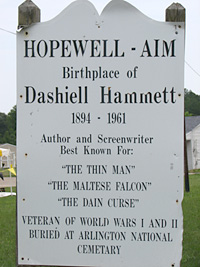

9-21, Fallon, NV, reading The Maltese Falcon AND Orem, UT, reading To Kill aMockingbird

9-22 Greeley, CO, reading Fahrenheit 451

9-23 Aurora, CO, reading The Call of the Wild

9-24 in Waukee, IA, home of last year’s truly inspiring read of The Shawl

9-25 Sheboygan, WI, reading Fahrenheit 451

9-26 Washington, DC, a good carwash, then National Book Festival Gala at the Library of Congress

9-27 Washington, DC, National Book Festival on the Mall, then collapse

To read more about these cities and their Big Read programs, visit http://www.neabigread.org/communities.php.

These cities and towns deserve a special advance salute for their hospitality in the midst of demanding planning for their Big Reads. I’ll add what I can to their celebrations of these terrific books by way of keynoters, stemwinders, and, in at least one instance, dubious dog-mushing expertise. But the real heavy lifting is theirs, bless them. I’m just along for the Ride.

And by the way, at least for the next fifteen days, the Big Read Blog has just gone daily. There’s a nonfiction novella in this cockamamie ride somewhere, and — along with the future of reading in America — I mean to find it. Wish me luck, and keep me company.