MUSIC and the BRAIN

Presented by the Library's Music Division and the Science, Technology and Business Division, through the generous support of the Dana Foundation. Project Chair, Dr. Kay Redfield Jamison, Psychologist and Professor of Psychiatry, Mood Disorders Center, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

“In music one must think with the heart and feel with the brain.” GEORGE SZELL

October 2008 opens a thought-provoking two-year cycle of lectures and special presentations at the Library of Congress that highlights an explosion of new research on music and the brain. Kay Redfield Jamison convenes scientists and scholars, composers, performers, theorists, physicians, psychologists, and other experts, under the auspices of the Library’s Music Division and Science, Technology and Business Division. All events in the series are free and open to the public. No tickets are required, but seating is limited, and early arrival is advised.

Ten compelling programs in the 2008-9 season feature a diverse lineup of speakers, including neuroscientsts Daniel J. Levitin, Antonio Damasio, Aniruddh D. Patel, and Steven Brown. Science, music and medicine converge in talks exploring a range of topics–the role of music and human evolution, and the universality of music across cultures; how the human brain is designed to perceive, understand, and like music; how the perception of music and the response to it is deeply rooted in human biology; how music conveys meaning and emotion; depression and creativity; and music, the brain, and behavior.

"Music hath charms to soothe a savage breast"–and myriad other powers as well. Music may heal our minds and hearts, enhance learning and build mental acuity, annoy or frighten us.

Music can make us weep, and one scientist proposes that it provides great pleasure as it does so. Today, investigators in a variety of fields including neuroscience, anthropology, and psychology are coming closer to identifying and quantifying how music works on the brain, affects our consciousness, behavior and culture, entertains us, enriches our emotional lives, and communicates in ways we can never quite verbalize.

Music and the Brain takes a look at the rapidly expanding field of "neuromusic," new research at the intersection of cognitive neuroscience and music. What went on in Charlie Parker’s medial prefrontal cortex as he started soloing on Ornithology? When you coo to your baby, are you stimulating a part of her brain that’s hard-wired for music? Can music bring down governments, or chase away criminals? With fascinating explorations into music’s relationship to human evolution, language and communication, social behavior, culture and education, these are intriguing offerings, slated for webcasts, podcasts and a radio hour.

For a complete webcast, check the Library of Congress website two weeks

after each Music and the Brain event.

Re the Music and the Brain series, this is all updated material since the

brochure was prepared.

All events are open to the public. No tickets required.

Pre-Concert Presentations

6:15 pm (Whittall Pavilion), concert follows at 8:00pm

October

17 “Homo Musicus: How Music Began”

October

17 “Homo Musicus: How Music Began”

Ellen Dissanayake, University of Washington, author of Art and Intimacy:

How the Arts Began (2000)

The universally-observed interaction between mothers and infants, commonly and even dismissively called "baby talk," is composed of proto-aesthetic, temporally-organized elements that Ellen Dissanayake suggests are the origin of human music. Because infants are born ready to engage in these encounters and to prefer their visual, vocal, and gestural components to any other sight or sound, one could claim that humans are innately prepared to be musical.

October 24 “The Brain on Jazz—Neural Substrates of

Spontaneous Improvisation”

Charles J. Limb, School of Medicine and Peabody Institute, Johns Hopkins

University

Many scientists have examined music cognition--how the brain permits music to be perceived and learned--but few have studied brain activity while music is being spontaneously created, or improvised. Dr. Limb’s recent research with jazz pianists reveals increased brain activity during improvisation in the medial prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain linked with self-expression and activities that convey individuality. In addition, broad areas of the lateral prefrontal cortex, thought to be linked to self-censoring, were turned off, or deactivated. "Without this type of creativity, humans wouldn’t have advanced as a species," Limb says. "It’s an integral part of who we are."

October 30 “Dangerous Music”

Jessica Krash, George Washington University and Norman Middleton, Library

of Congress Music Division

Artistic anathemas, musical mayhem, and cultural conundrums such as "the devil's music"- Middleton and Krash explore the psychological and social issues associated with the human tendency toward censorship of musical expression, as well as what has been described as "suicide-by-music" and crimes that have been connected to musical genres.

November 7 “The Music of Language and the Language of Music”

Aniruddh D. Patel, author of Music, Language and the Brain (2007)

and senior fellow, Neurosciences Institute, San Diego, California

In our everyday lives language and instrumental music are obviously different things. Dr. Patel, Esther J. Burnham Fellow at the Neurosciences Institute and author of "Music, Language, and the Brain" discusses some of the hidden connections between language and instrumental music that are being uncovered by empirical scientific studies.

*** CANCELLED (Dec. 5) *** to be rescheduled in 2009

December 5 “Why Do Listeners Enjoy Music That Makes Them

Weep?”

David Huron, author of Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology

of Expectation (2006) and head, Cognitive and Systematic Musicology

Laboratory, Ohio State University

Tearing of the eyes, nasal congestion, a constriction in your throat, and erratic breathing -- your doctor would conclude that you are suffering from a severe allergic reaction. But in special circumstances, music can evoke precisely these symptoms. Music-induced weeping represents one of the most powerful and potentially sublime experiences available to human listeners. How does music evoke feelings akin to sadness or grief? And why do people willingly listen to music that may make them cry? Modern neuroscience provides helpful insights into music-induced weeping, how sounds can evoke sadness or grief, and why such sounds might lead to "a good cry."

March 5 “From Mode to Emotion in Musical Communication”

Steven Brown, Director, NeuroArts Lab, McMaster University

Music employs a number of mechanisms for conveying emotion. Some of them are shared with other modes of expression (speech, gesture) while others are specific to music. The most unique way that music communicates emotion is through the use of contrastive scale types. While Westerners are familiar with the major/minor distinction, the use of contrastive scale types in world musics is universal.

March 13 “Halt or I'll Play Vivaldi! Classical Music as Crime

Stopper”

Jacqueline Helfgott, Seattle University, author of Criminal Behavior:

Theories, Typologies, and Criminal Justice (2008), and Norman Middleton,

Library of Congress Music Division

Helfgott and Middleton examine the use of classical music by law enforcement and other cultural institutions as social control, to quell and prevent crime. Their conversation touches on how classical music is viewed in contemporary culture, how it can be a tool for discouraging criminal activity and anti-social behavior, as well as its history as a mind-altering experience.

March 27 “The Mind of the Artist”

Michael Kubovy and Judith Shatin, University of Virginia

Debate has long raged about whether and how music expresses meaning beyond its sounding notes. Kubovy and Shatin discuss evidence that music does indeed have a semantic element, and offer examples of how composers embody extra-musical elements in their compositions. Kubovy is a cognitive psychologist who studies visual and auditory perception, and Shatin is a composer who explores similar issues in her music.

LECTURE AND BOOKSIGNING

Tuesday,

November 18, 2008 at 7:00 pm

Tuesday,

November 18, 2008 at 7:00 pm

Coolidge Auditorium (open to the public, no tickets required)

The World in Six Songs: How the Musical Brain Created Human Nature

Daniel Levitin, author of This is Your Brain on Music, will talk about his new book, The World in Six Songs: How the Musical Brain Created Human Nature. He will then sign copies of his book, which will be available for sale.

Director of McGill University’s Laboratory for Musical Perception, Cognition, and Expertise, and best-selling author of "This is Your Brain on Music," Dr. Levitin blends cutting-edge scientific findings with his own sometimes hilarious experiences as a former record producer and still-active musician. Earning advance raves from reviewers like Sting and Sir George Martin, the Beatles’ producer, his new book takes readers on a journey of the world through six types of songs-friendship, joy, comfort, knowledge; religion/ritual, and love.

SYMPOSIUM

Tuesday, February 3, 2009 at 7:00 pm – Whittall Pavilion

DEPRESSION

AND CREATIVITY

DEPRESSION

AND CREATIVITY

Presented in conjunction with “Mendelssohn on the Mall,” a special

celebration marking the bicentennial anniversary of Felix Mendelssohn, who

died after a severe depression following the death of his sister Fanny,

also a musician and an extraordinarily gifted composer.

Looking at the expression of emotion in both Western and non-Western musics, Brown invokes the theory of Clore and Ortony, who posit three categories of emotions 1) "outcome" emotions related to the outcomes of goal-directed actions (e.g., happiness, sadness); 2) "aesthetic" emotions related to the appraisal of the quality of objects (e.g., like, dislike); and 3) "moral" emotions related to an assessment of the agency of individuals’ actions (e.g., praise, scorn). While representational art-forms like theater or dance can represent all three categories, music is probably most adept at expressing "outcome" emotions, such those that sit along the happy/sad spectrum.

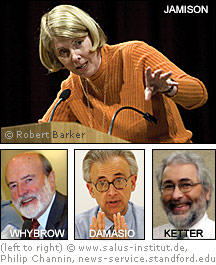

Kay Redfield Jamison, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and co-director of the Johns Hopkins Mood Disorders Center at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, convenes a discussion of the effects of depression on creativity. She is joined by three distinguished colleagues in the fields of neurology and neuropsychiatry: Antonio Damasio, Professor of Neuroscience, Neurology, and Psychology and co-founder and director of the Brain and Creativity Institute, University of Southern California; Terence Ketter, professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and Chief, Bipolar Disorders Clinic, Stanford University; and Peter Whybrow, Director, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, University of California at Los Angeles.

“Music and the Brain” is presented

by the Music Division and the Science, Technology and Business Division,

Library of Congress,in collaboration with the Johns Hopkins Mood Disorders

Center; and with the generous support of the Dana Foundation.