|

|||

|

NIOSH Publication No. 2006-144:Workplace Violence Prevention Strategies and Research Needs |

September 2006 |

|

This report summarizes discussions that took place during Partnering in Workplace Violence Prevention: Translating Research to Practice—a landmark conference held in Baltimore, Maryland, on November 15–17, 2004. The report does not include a documented review of either the literature on WPV in general or intervention effectiveness research in particular. In addition, the authors have consciously avoided adding the NIOSH perspective to this report or otherwise augmenting its content. We have preferred to represent as accurately as possible the information, ideas, and professional judgments that emerged from the discussions that took place at the Baltimore workshop. Contents

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Report from the Conference

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John Howard, M.D. Director, National Institute for OccupationalSafety and Health Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| ASIS | American Society for Industrial Security |

| BLS | Bureau of Labor Statistics |

| CAL/OSHA | California/Occupational Safety and Health Administration |

| CFOI | Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries |

| IPV | intimate partner violence |

| MADD | Mothers Against Drunk Driving |

| NIOSH | National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health |

| NTOF | National Traumatic Occupational Fatalities |

| OSHA | Occupational Safety and Health Administration |

| PSA | public service announcement |

| WPV | workplace violence |

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recognizes the cosponsoring organizations that provided financial support for various aspects of the conference: Corporate Alliance to End Partner Violence, Verizon Wireless, State Farm Insurance Company, American Society for Industrial Security (ASIS) International, American Association of Occupational Health Nurses, Liz Claiborne, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and Injury Prevention Research Center—University of Iowa.

The conference and this summary report would not have been possible without the enthusiastic efforts of the conference planning committee (see the list that follows). Members worked diligently to structure the conference, and NIOSH thanks them for their time, energy, and insight. Corinne Peek-Asa, Jonathan Rosen, Kim Wells, and Carol Wilkinson presented plenary session overviews and facilitated breakout sessions on each type of workplace violence (WPV). Meg Boendier, Stephen Doherty, Kathleen McPhaul, and Corinne Peek-Asa provided the working group session summaries that formed the basis for this report. NIOSH appreciates the technical contributions of all these persons and their dedication to the understanding and prevention of WPV.

Nancy Stout, Director, NIOSH Division of Safety Research, and Tim Pizatella, Deputy Director, Division of Safety Research, provided guidance and support. Lynn Jenkins, NIOSH, prepared and presented a summary of the conference themes and issues for use in preparing this report. The following NIOSH staff members prepared, organized, and reviewed conference material: Lynn Jenkins, Matt Bowyer, Dan Hartley, Kristi Anderson, Barbara Phillips, and Brooke Doman. Matt Bowyer and Herb Linn summarized conference notes and summary reports, drafted the text, and revised the report.

Jane Weber and Gino Fazio provided editorial and production services.

Matt E. Bowyer, Chair Gregory T. Barber, Sr. Patricia D. Biles Bill Borwegen Ann Brockhaus Pamela Cox Butch de Castro Stephen Doherty Mary Doyle Paula Grubb Michael Hodgson E. Lynn Jenkins |

Kathleen McPhaul Susan Melnicove Corinne Peek-Asa Robyn Robbins Rashuan Roberts Gene Rugala Robin Runge Linda M. Tapp Mary Tyler Kim Wells |

Mention of a company or product does not constitute endorsement by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). In addition, citations to Web sites external to NIOSH do not constitute NIOSH endorsement of the sponsoring organizations or products. Furthermore, NIOSH is not responsible for the content of these Web sites.

The recommendations and opinions expressed in this document are those of individual participants in the conference and may not represent the opinions and recommendations of all members, or of the organizations they represent.

To receive documents or other information about occupational safety and health topics, contact NIOSH at

NIOSH Publications Dissemination

4676 Columbia Parkway

Cincinnati, OH 45226–1998

Telephone: 1–800–35–NIOSH (1–800–356–4674)

Fax: 513–533–8573

E-mail: pubstaft@cdc.gov

or visit the NIOSH Web site at www.cdc.gov/niosh

In North Carolina, two masked men walked into a food mart, killed the 44-year-old male co-owner by shooting him several times with a handgun, ripped away the cash drawer, and fled from the scene. In Massachusetts, a 27-year-old mechanic in an autobody shop was fatally shot in the chest by a customer after they argued about repairs. In Virginia, an ongoing argument between two delivery truck loaders at a furniture company distribution warehouse ended abruptly as one pulled a gun and shot the other to death. In South Carolina, a 24-year-old woman who worked in a grocery store was taken hostage at gunpoint and then shot to death with multiple shotgun blasts by her 20-year-old ex-boyfriend. |

These tragic examples of violence in U.S. workplaces represent a small sample of the many violent assaults that occur in U.S. workplaces annually.*

| *These fatal, gun-related cases do not represent the huge number of violent incidents that result in nonfatal injuries or no injuries, or that involve other types of weapons. Also, these cases do not adequately represent the many industry sectors and worker populations that face the risk of violent assault at work. |

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, an estimated 1.7 million workers are injured each year during workplace assaults; in addition, violent workplace incidents account for 18% of all violent crime in the United States [Bureau of Justice Statistics 2001]. Liberty Mutual, in its annual Workplace Safety Index, cites “assaults and violent acts” as the 10th leading cause of nonfatal occupational injury in 2002, representing about 1% of all workplace injuries and a cost of $400 million [Liberty Mutual 2004]. During the 13-year period from 1992 to 2004, an average of 807 workplace homicides occurred annually in the United States, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI) [BLS 2005]. The number of deaths ranged from a high of 1,080 in 1994 to a low of 551 workplace homicides in 2004, the lowest number since CFOI began in 1992. Although the number of deaths increased slightly over the previous year in both 2000 (677) and 2003 (631), the overall trend shows a marked decline [BLS 2005]. From 1992 through 1998, homicides comprised the second leading cause of traumatic occupational injury death, behind motor-vehicle-related deaths. In 1999, the number of workplace homicides dropped below the number of occupational fall-related deaths, and remained the third leading cause through 2003. In 2004, homicides dropped below struck-by-object incidents to become the fourth leading cause of fatal workplace injury (see Figure 1) [BLS 2005].

It is not altogether clear what factors may have influenced the overall decreasing trend in occupational homicides for the period 1992 through 2004, and whether the decreasing numbers will be sustained in subsequent years. Since robbery-related violence results in a large proportion of occupational homicides, certain trends (e.g., economic fluctuations) are likely to have contributed to the decreasing toll. The reduction may partially stem from the efforts of researchers and practitioners to address robbery-related WPV especially through intervention evaluation research and dissemination and implementation of evidence-based strategies. The reduction may be partially explained by the efforts of Federal, State, and local agencies and other policy-makers to develop statutes, administrative regulations, and/or technical information for WPV prevention as a result of improved recognition and understanding of the risks for WPV. Whatever the reasons behind the trend, future research and prevention efforts should focus on identifying, verifying, and replicating successes—such as reductions in robbery-related (Type I) violence—and identifying and addressing those types of WPV where little or no change has occurred. The fact that violence-related deaths increased over previous years’ totals in both 2000 and 2003 raises questions about the sustainability of the overall downward trend and whether the occupational homicide experience in the United States may in fact be leveling.

|

| Figure 1. The four most frequent fatal work-related events, 1992–2004. NOTE: Data from 2001 exclude fatalities resulting from the September 2001 terrorist attacks. (SOURCE: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Census of Fatal Occupational injuries, 2004.) |

A few of the violent incidents that occur in workplaces and result in deaths or serious injuries to workers are reported widely and prominently on TV and radio broadcasts, newspaper pages, and media Web sites. As indicated, WPV incidents arise out of a variety of circumstances: some involve criminals robbing taxicab drivers, convenience stores, or other retail operations; clients or patients attacking providers in health care or social service offices; disgruntled workers seeking revenge; or domestic abuse that spills over to the workplace (see Table 1). More recently, the threat of another form of criminal violence—terrorism—hangs over the nation’s workplaces. Yet many employers, managers, and workers are not particularly aware that the potential for violence is a risk facing them in their own workplaces. The public is generally not aware of either the scope or the prevalent types of violence at work. In fact, it has been only within the last two decades that the problem of violent workplace behavior has come into focus—largely resulting from improvements in occupational safety and health surveillance—as a leading cause of workplace fatality and injury in many industry sectors in the United States.

When the National Traumatic Occupational Fatalities (NTOF) surveillance system was developed by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) in the 1980s, an accurate count of workplace traumatic injury deaths in the United States was available for the first time [NIOSH 1989]. In 1988, NIOSH published its first article disseminating data on the magnitude of the national workplace homicide problem [Hales et al. 1988]. This article presented results indicating that worker against worker violence, which continues to be emphasized by the media, is only a small portion of the WPV that occurs daily in the United States.

The U.S. Department of Labor, through its Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the BLS, brought increased focus on occupational violence through compliance, surveillance, analysis, and information dissemination efforts. Although no specific Federal regulations then (or now) addressed WPV, OSHA began to cite employers where violent incidents occurred under the General Duty Clause [29 USC* 654 5(a)(1)], which requires employers to provide safe and healthful work environments for workers. OSHA also provided and disseminated, through reports and the OSHA Web site, violence prevention guidance for high risk sectors and populations such as health care, social services, late-night retail establishments, and taxi and livery drivers. The BLS has clarified the injury and fatality risks to workers from violent incidents through its nonfatal and fatal injury surveillance and special analyses of characteristics of occupational violence.

| *United States Code. |

In the mid 1990s, as more researchers were becoming engaged in the study of occupational violence, the California Occupational Safety and Health Administration (Cal/OSHA) developed a model that described three distinct types of WPV based on the perpetrator’s relationship to the victim(s) and/or the place of employment [Cal/OSHA 1995, Howard 1996]. Later, the Cal/OSHA typology was modified to break Type III into Type III and Type IV, creating the system that remains in wide use today [IPRC 2001]. (See Table 1) This typology has proven useful not only in studying and communicating about WPV but also in developing prevention strategies. Certain occupations, such as taxicab drivers and convenience store clerks, face a higher risk of being murdered at work [IPRC 2001], while health care workers are more likely to become victims of nonfatal assaults [NIOSH 2002].

Since nearly all of the U.S. workforce (more than 140 million) can potentially

be exposed to or affected by one of the four types of WPV, occupational

safety and health practitioners and advocates should be concerned. Examples

of high-risk industries include the retail trade industry, whose workers

are most often affected by Type I (criminal intent violence), and the health

care industry, whose workers may generally be affected most by Type II

(client, customer, or patient violence). Although all four types of WPV

can potentially occur in any workplace, Type III (worker-on-worker violence)

and Type IV (personal relationship violence, also known as intimate partner

violence), are more likely to occur across all industry sectors.

Table 1. Typology of workplace violence |

|

Type |

Description |

|---|---|

| I: Criminal intent | The perpetrator has no legitimate relationship to the business or its employee, and is usually committing a crime in conjunction with the violence. These crimes can include robbery, shoplifting, trespassing, and terrorism. The vast majority of workplace homicides (85%) fall into this category. |

| II: Customer/client | The perpetrator has a legitimate relationship with the business and becomes violent while being served by the business. This category includes customers, clients, patients, students, inmates, and any other group for which the business provides services. It is believed that a large portion of customer/client incidents occur in the health care industry, in settings such as nursing homes or psychiatric facilities; the victims are often patient caregivers. Police officers, prison staff, flight attendants, and teachers are some other examples of workers who may be exposed to this kind of WPV, which accounts for approximately 3% of all workplace homicides. |

| III: Worker-on-worker | The perpetrator is an employee or past employee of the business who attacks or threatens another employee(s) or past employee(s) in the workplace. Worker-on-worker fatalities account for approximately 7% of all workplace homicides. |

| IV: Personal relationship | The perpetrator usually does not have a relationship with the business but has a personal relationship with the intended victim. This category includes victims of domestic violence assaulted or threatened while at work, and accounts for about 5% of all workplace homicides. |

| Sources: CAL/OSHA 1995; Howard 1996; IPRC 2001. | |

WPV includes a much wider range of behaviors than just overt physical assaults that result in injury or death. Thus, WPV has been defined as “violent acts, including physical assaults and threats of assault, directed toward persons at work or on duty” [NIOSH 1996]. It is widely agreed that violence at work is underreported, particularly since most violent or threatening behavior—including verbal violence (e.g., threats, verbal abuse, hostility, harassment) and other forms, such as stalking—may not be reported until it reaches the point of actual physical assault or other disruptive workplace behavior.

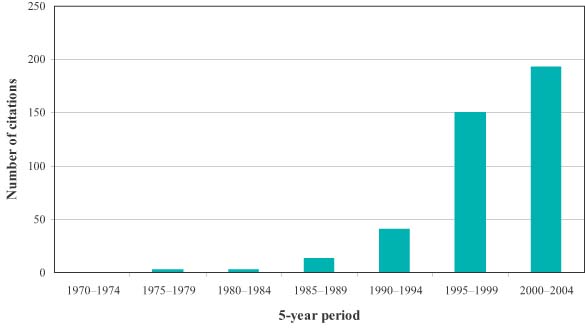

Most of the research that was conducted over the last half of the decade of the 90s was published in scientific and professional journal articles. Figure 2 shows the dramatic increase in the number of research articles published in the medical literature that dealt with WPV from the 1980s, when the occupational fatality surveillance data first showed that occupational homicide was the second leading cause of traumatic occupational death, through 2004 [National Library of Medicine 2005]. Similar results were obtained in searches of the occupational safety and health, business, and social science literature.

|

| Figure 2. Medline entries for WPV for 5-year periods from 1970 to 2004. |

In April 2000, the University of Iowa Injury Prevention Research Center sponsored a meeting entitled Workplace Violence Intervention Research Workshop in Washington, D.C. The workshop brought together invited participants to discuss WPV and recommend strategies for addressing this national problem. The workshop recommendations were published as Workplace Violence: Report to the Nation in February 2001 [IPRC 2001]. This report identified key research issues and called for funding to address these research needs.

In December 2000, Congress appropriated $2 million to NIOSH to develop a WPV Research and Prevention Initiative consisting of intramural and extramural research programs targeting all aspects of WPV. Most of the money was used to fund new research grants undertaken by extramural researchers. Intramural research efforts focused on collaborating with other agencies to collect improved data on WPV from workers and employers, convening a Federal interagency task force to coordinate Federal research activities, and collaborating with other groups to raise awareness of WPV and disseminate information developed through the Initiative.

In June 2002, the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime hosted a symposium on WPV bringing together a multidisciplinary group to look at the latest thinking in prevention, intervention, threat assessment and management, crisis management, and critical incident response. The results were published in March 2004 in Workplace Violence: Issues in Response [Rugala and Isaacs 2004].

As part of the WPV Research and Prevention Initiative, NIOSH convened a series of stakeholder meetings on WPV during 2003. The purpose of these meetings was to allow subject matter experts from business, academia, government, and labor organizations to collectively discuss WPV in terms of current progress, research gaps, and potential collaborative efforts. Stakeholders with interest in the following topic areas met during the timeframes noted:

One of the recurring themes that emerged from the stakeholder discussions was the need for a national conference on WPV prevention. In January 2004, NIOSH assembled a diverse planning committee to begin developing this forum. On November 15–17, 2004, NIOSH held, for the first time, a national conference on WPV prevention, entitled Partnering in Workplace Violence Prevention: Translating Research to Practice [NIOSH 2004].

This document is the final product resulting from the November 2004 conference. It summarizes what conference participants think are key strategies required for successful WPV prevention, further research and communication needs, barriers and gaps that impede prevention, and strategies for addressing them. The document also summarizes participants’ thoughts about potential partners among Federal, State, and private agencies with the resources and skills necessary to collaborate in prevention efforts, conduct further research, and facilitate appropriate regulations. It is hoped that this report will serve several important purposes—to raise awareness of employers, workers, policy makers, and the public in general to the fact that WPV continues to be a major public health issue; to assist business and labor leaders in adopting effective prevention programs and strategies; to aid researchers in identifying future projects; and to prompt government officials to consider more comprehensive national programs.

During the conference, NIOSH assembled a diverse group of experts representing the four WPV typologies and the various disciplines engaged in WPV research and prevention efforts (see Appendix for a full list of participants). The conference was structured to give participants an opportunity to discuss successful WPV prevention strategies, barriers and challenges to WPV prevention, major research and information dissemination gaps, and potential roles for various organizations in WPV prevention over the next decade. In order to address the objectives in an effective manner, discussion points were posed to participants in breakout sessions that were divided into four WPV typologies: Criminal Intent (Type I), Customer/Client (Type II), Worker-on-Worker (Type III), and Personal Relationship (Type IV).

The conference included the following:

This report should provide a useful framework for thinking about the current state of WPV research, prevention, and communication activities in the United States. Chapter 2 presents a discussion of barriers and gaps that impede the development and implementation of WPV prevention programs. Chapter 3 summarizes the best WPV strategy/program practices presented by conference participants. This summary represents an implicit template for addressing WPV prevention on a company, corporate, agency, and national level and includes strategies both general and specific to the four types of WPV. Chapter 4 presents a discussion of general research needs; Chapter 5 addresses the importance of linking research findings to practical prevention efforts. One of two important themes of the conference—partnership—is the focus of discussion in Chapter 6. Included are some ideas about partners who should be involved in national, community, and company collaborations, and what they could be doing to address WPV. Chapter 7 provides some concluding thoughts and a call to action for potential collaborators in a national WPV prevention effort. The Appendix provides a full list of conference participants.