| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

Booth Elementary Puts Reading First

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Despite the promises of his school's staff to get him the help he needed, Mary's 7-year-old grandson could not read. "I'm real stupid," he would tell her. "Everybody knows how to read except me. Kids make fun of me at school and stuff because I'm so stupid."

Things turned around when Mary gained custody of her grandson, following the loss of his father, and transferred him to Anna F. Booth Elementary, her neighborhood school. Five months later, her grandson was not only reading well but also loving school. "They changed a child's life," says Mary about the teachers at Booth.

Reading achievement at Booth in Bayou la Batre, a city in Mobile County, Ala., has been on the rise since it implemented a U.S. Department of Education grant in 2003 that provides funding and other resources to help struggling readers in grades K-3 at disadvantaged schools. This year, Booth's 3rd-grade readers ranked in the 63rd percentile on the Stanford Achievement Test Series—a far leap from the disappointing 29th-percentile ranking it received five years ago on the standardized exam used nationwide. That means that Booth's 3rd-grade students are performing as well as or even better than 63 percent of their counterparts nationally and that the school was considerably closer to ensuring all children could read by the end of the third grade, a goal of the federal Reading First program.

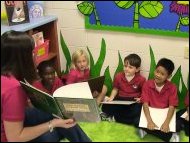

Reading intervention teacher Ellen Cobb helps students with vocabulary-building strategies. Photos courtesy of Booth Elementary School.  Kindergarteners smile for the camera.  Jennifer Parker teaches reading to a small-group of second-graders. |

"I'm not an idealist at all, because I'm steeped in reality," says Principal Lisa Williams about her rural, high-poverty school, where 89 percent of the students qualify for federally subsidized meals. "But I really believe Reading First can change the course of a community."

She credits the program with helping the school to regroup academically in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, which devastated the coastal town, displacing 70 percent of Booth's students and wreaking havoc on the local fishing industry. A primary source of livelihood for the area, this commerce has attracted a large Asian population from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, who account for nearly one-quarter of the school's population and primarily 21 percent of the children learning English.

But despite these great challenges to learning, because the professional development had been so intense and the teachers were so empowered by the knowledge they had gained, they weren't intimidated by them. "After Katrina," said Williams, "I never once had a staff member express concern to me that the impact would negatively affect student achievement."

Academic gains at Booth have been so steady that for the past three years it has earned the state's prestigious "Torchbearer" designation as a high-performing school serving a high-need population. Moreover, it was one of only nine schools in the state awarded this distinction in 2008, even though Alabama had toughened its standards for that school year. According to results on the state exam (Alabama uses both the Stanford test series and its own assessment to measure student achievement), at least 90 percent of Booth's students in grades 3-5 proved proficient or above in reading and math, with more than half scoring in the "exceeds standards" category.

The bar had been raised, explains Williams. "I believe that students who live in poverty are at times actually held there by patronizing teachers—perhaps sweet but nonetheless patronizing teachers—who give them low-level assignments that meet their expectations."

However, she says initially there was the challenge of getting the teachers to recognize and accept the need for change, "to view the [Reading First] grant award in a positive light rather than as an indication they were somehow inept." Meetings were held to look at student performance data in comparison to that of other schools with similar demographics as well as to discuss national school reform and the federal agenda to prepare students for higher education and today's global workforce. "So it shifted from being just 'this personal need that you have as a teacher' to being 'this is a national crisis,'" says Williams. In other words, "Understand that you're not being singled out. There's a need for change throughout the nation."

Julie Salmons, who coaches teachers in reading and tutors struggling readers, believes the data meetings spurred by Reading First helped to create and maintain a "sense of urgency to increase student achievement"—which is why, she says, the meetings are far from being merely a review of numbers.

"We talk about each child, and as a group come up with the best way to meet the needs of that child. ... If it were my child, I would be more than happy for him or her to be discussed in this way—in a data meeting—because everybody's working together to help that child. Certainly six heads are better than one."

While the U.S. Department of Education Reading First grant—whose framework provided a focus on teacher training and collaboration, research-based practices and effective use of data—was essential to change at Booth, Williams lists four other factors she considers of equal importance for schoolwide success:

- An engaging, empowering school climate where factors such as poverty, migrant status, disability and first-language are not considered correlates or excuses for lack of performance;

- Job-imbedded staff development that is "results-driven" and includes expert teachers (or coaches) modeling instruction, rather than off-site training disconnected to addressing the specific needs of the children at the school;

- An intervention plan supported by a staggered school day schedule that allows both classroom teachers and support personnel—such as the teachers for special education, Title I and English as a second language (ESL)—to work closely with at-risk students several times a day;

- Instruction and ongoing assessments aligned with a standards-based curriculum.

Results of these strategies also were evident to other educators in Mobile County. When Booth's staff attended a data meeting with the feeder middle school, Williams says the teachers there told her that they had noticed a sharp difference in the literacy level of new students from Booth over the past few years.

"They're thanking us for sending children who can read, because at one time we were sending children who were still learning to read instead of reading to learn."

Unsubscribe

To unsubscribe from The Achiever:

- Send email to listserv@listserv.ed.gov

- Write in the body of the message: unsub nochildleftbehind

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| |

||||||||||||