Request for Assistance in...

Preventing Knee Injuries and Disorders in Carpet Layers

NIOSH ALERT: May 1990

DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 90-104

|

Request for Assistance in...Preventing Knee Injuries and Disorders in Carpet LayersNIOSH ALERT: May 1990 |

WARNING!Serious knee injuries frequently result when carpet layers kneel on hard surfaces and use a knee kicker to install carpet. |

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) requests assistance in preventing knee injuries and disorders among carpet layers. These workers frequently report bursitis of the knee, fluid buildup requiring knee aspiration (knee taps), skin infections of the knee, and a variety of knee symptoms that are caused by frequent kneeling on hard surfaces and use of the knee kicker for stretching wall-to-wall carpet.

Although kneeling cannot be eliminated, carpet layers should wear protective knee pads whenever kneeling on hard surfaces. In addition, they should use the power stretcher--a safe alternative to the knee kicker that does not use the knee. Employers should ensure that each carpet layer is trained in the proficient use of the power stretcher and that a sufficient number of these devices are available to each crew of carpet installers.

NIOSH requests that the recommendations in this Alert be brought to the attention of carpet layers and contractors by the following individuals: employers of carpet layers (such as building contractors and carpet retailers), trade union representatives, instructors at carpet installation schools, manufacturers and dealers of carpet and carpet-stretching devices, editors of appropriate trade journals, and safety and health officials.

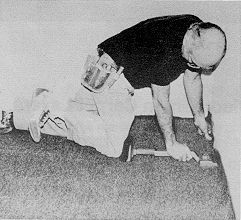

Approximately 100,000 carpet layers are employed in the United states [Green and Epstein 1985]. Carpet layers make up less than 0.06% of the U.S. workforce, but they file 6.2% of all workers' compensation claims for traumatic knee injury--a rate that is 108 times that expected in the total workforce and the highest rate of any occupation reporting such claims [Tanaka et al. 1982]. This rate is also high for tilesetters (53 times that expected) and floorlayers (46 times that expected), both of whom perform work that requires kneeling on hard floors. Carpet layers share this risk factor, but they also use the knee kicker to stretch carpet for wall-to-wall installation. Workers using this device (Figure 1) generate force by striking the tool with one knee to stretch the carpet tightly. The area just above the kneecap absorbs the impact [Garstein 1979; Duffin 1962].

Figure 1. A carpet layer using a knee kicker.

Since the late 1950s, the mass production of carpet for wall-to-wall installation has increased dramatically. As a consequence, the use of the knee kicker has become widespread among carpet layers who install wall-to-wall carpets in homes and offices. The Carpet and Rug Institute reports that 1.3 billion square yards of carpet were manufactured in the United states in 1988, and most of these were used for wall-to-wall installation [Carpet and Rug Institute 1989].

During a typical installation, carpet layers spend about 75% of the time on their hands and knees. The carpet layer first prepares the floor by nailing tack strips along the perimeter of the room. During this activity the knees are in direct contact with the hard surface. After the padding material is installed, the carpet is spread and cut to the size and shape of the room. The carpet layer then uses the knee kicker to engage an edge of the carpet onto the tack strips. Only mild kicks are required for this purpose. However, very strong kicks are applied when the carpet is stretched from wall to wall. According to a biomechanical study, the average impact of such kicks exceeds 3,000 newtons (675 pounds)--about three to five times the body weight. During a typical installation these strong knee kicks are repeated 120 to 140 times per hour [Bhattacharya et al. 1985].

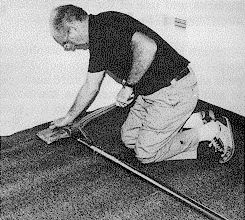

A hand/arm-operated device known as a power stretcher is an alternative carpet-stretching tool that uses lever arm and cog mechanics [Garstein 1979; Duffin 1962]. Use of this device (Figure 2) produces no impact trauma to the knee because power stretchers require no knee action. The power stretcher can be adjusted to various lengths with extension tubes for use in large or small rooms.

Figure 2. A carpet layer using a power stretcher.

No specific Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standards apply to the carpet-laying process or to the prevention of work-related knee disorders affecting carpet layers.

In the mid-1980s, NIOSH conducted a study of union tradesmen that included questionnaires, interviews, and medical examinations [Thun et al. 1987]. Compared with workers who seldom kneel and do not use a knee kicker, carpet layers more frequently reported bursitis of the knee (20% versus 6%), fluid buildup requiring knee aspiration (knee taps) to remove blood and water (32% versus 2%), skin infections of the knee (7% versus 2%), and a variety of knee symptoms. Furthermore, carpet layers often leave the trade after knee damage develops and thus would not be included in a cross-sectional study such as this. The actual number of knee injuries and the extent of damage may therefore be greater than these statistics indicate.

Even though carpet layers spend about 75% of their time kneeling, only about half of those surveyed reported regular use of knee pads, and these workers reported using them less than half of the time.

The study concluded that knee disorders suffered by carpet layers were caused by kneeling and the use of the knee kicker.

In 1988, NIOSH conducted a questionnaire survey of carpet layers who had used the power stretcher [Tanaka et al. 1989]. Almost all respondents (more that 95%) reported that the power stretcher was easy to use, produced a better quality of carpet installation, and "saved" their knees. Although one-third of the respondents reported that the power stretcher slowed the progress of the job, two-thirds reported that it was "helpful in doing a quick job." The primary disadvantage of the stretcher (reported by 59%) was that its size and weight made it difficult to carry.

Many respondents (39%) reported that the power stretcher was not always available at the job site. Cost may limit the availability and use of the power stretcher because these tools cost at least $500 and are usually provided by the employer. The carpet layer usually owns his own knee kicker, which costs about $100.

Both kneeling and use of the knee kicker contribute significantly to the high frequency of carpet layers' knee disorders. Identification of these two risk factors provides opportunities for prevention.

Carpet layers spend the majority of their work time on their knees, but they seldom use protective knee pads. A safe alternative to the knee kicker is the power stretcher, which eliminates impact trauma to the knee.

NIOSH recommends the following measures to prevent or reduce knee disorders among carpet layers:

--initiate or intensify efforts to educate carpet layers about the hazards of kneeling and using the knee kicker, and

--encourage carpet layers to wear knee pads and to use the power stretcher.

Comments, questions, or requests for additional information should be directed to one of the following NIOSH staff members.

For medical information, please contact

Shiro Tanaka, M.D.

Medical Officer

Mail Stop R-21,

Division of Surveillance, Hazard Evaluations, and Field Studies

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

4676 Columbia Parkway

Cincinnati, Ohio 45226Telephone (513) 841-4410

For engineering information, please contact

Daniel Habes, Industrial Engineer

Mail Stop C-24

Division of Biomedical and Behavioral Science

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

4676 Columbia Parkway

Cincinnati, Ohio 45226Telephone (513) 533-8291

We greatly appreciate your assistance, which is crucial to protecting the lives of American workers.

| [signature] J. Donald Millar, M.D., D.T.P.H. (Lond.) Assistant Surgeon General Director, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Centers for Disease Control |

Bhattacharya A, Mueller M, Putz-Anderson V [1985]. Traumatogenic factors affecting the knees of carpet installers. Appl Erg 16:243-250.

Carpet and Rug Institute [1989]. Personal communication with Shiro Tanaka, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Duffin DJ [1962]. The essentials of modern carpet installation. 2nd ed. New York NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., pp 119-126.

Garstein AS [1979]. The how-to handbook of carpets. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., p. 150.

Green GP, Epstein RK, eds. [1985]. Employment and earnings, 1985. Vol. 32, No. 1. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, p. 179.

Tanaka S, Smith AB, Halperin W, Jensen R [1982]. Carpet- layer's knee (letter to the editor). N Engl J Med, 307:1275-1276.

Tanaka S, Lee ST, Halperin WE, Thun MJ, Smith AB [1989]. Reducing knee morbidity among carpet layers. Am J Public Health 79:334-335.

Thun MJ, Tanaka S, Smith AB, Halperin WE, Lee ST, Luggen ME, Hess EV [1987]. Morbidity from repetitive knee trauma in carpet and floorlayers. Br J Ind Med 44:611-620.