|

| |

Photographs |

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Eskimos contracted and died from influenza in disproportionately high numbers. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

Panoramic view of Baltimore, Maryland. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

Surgeon General Rupert Blue. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| As movie theaters closed across the United States, audiences were forced to wait to see films such as Charlie Chaplain’s A Dog’s Life. Chaplain’s career was able to weather this delay but several small movie companies in Hollywood went bankrupt as a result of the pandemic. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

The swimmers who posed here at Seal Beach in 1917 discovered, in 1918, that state officials were prepared to close even California’s famous beaches to prevent the spread of the pandemic. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

During the influenza pandemic, the closure of many movie theaters meant that producers were forced to postpone the opening of many films. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Katherine Porter, who contracted influenza and nearly died in 1918, transformed her own experience of the pandemic into a classic of American literature. Pale Horse, Pale Rider is set in Denver during the 1918 pandemic.[Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

Coney Island in New York was the nation’s most famous amusement park but by 1918, amusement parks could be found all over America [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

c1905 Main St. and City Hall in Hartford, Connecticut. During the epidemic many homes and other buildings along Main St. were converted to emergency hospitals.[Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| c1920 The New London Harbor Lighthouse. New London was the first city in Connecticut to report cases of influenza to the Public Health Service. [Credit: The University of Connecticut] |

|

1912, Panoramic view of ‘2/5’ of the state of Delaware. The rapid spread of the pandemic led authorities in Delaware to close indefinitely nearly all public gathering places.[Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

c1910, The interior of W.B. Danforth Drugs in Wilmington, Delaware. Medicine was in high demand during the pandemic, and numerous claims of ‘cures’ for influenza began to spread. None, however, proved effective. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Nursing attracted ambitious and educated women from both the middle and working class. [Credit: Office of the Public Health Service Historian] |

|

An aerial view of the plaza and harbor in Pensacola, Florida. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

c1915. Dinner Hour on the docks in Jacksonville, Florida. Unsanitary conditions and a lack of understanding of how the disease was transmitted contributed to the spread of influenza. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

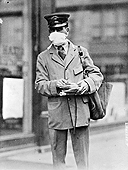

| Although people dutifully wore masks, these provided only a very limited protection against the influenza virus. [Credit: Office of the Public Health Service Historian] |

|

c1903 The Albion Hotel once stood adjacent to the Confederate Monument on Broad St. in Augusta, Georgia. Augusta was the hardest hit city in the state during the epidemic. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

Joseph Goldberger, one of the leading researchers in the PHS, studied influenza during the pandemic. But Goldberger had multiple interests and influenza research became less important to him in the years following 1918. [Credit: Office of the Public Health Service Historian] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Workers on rural and isolated plantations suffered as influenza attacked all of the islands. c. 1910-1925. |

|

Influenza hit Boise, shown here in 1909, in October. |

|

In July, an American soldier said that while influenza caused a heavy fever, it “usually only confines the patient to bed for a few days.” The mutation of the virus changed all that. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| More Americans died from influenza than died in World War I. [Credit: National Library of Medicine] |

|

When it came to treating influenza patients, doctors, nurses and druggists were at a loss. [Credit: Office of the Public Health Service Historian] |

|

Mail delivery was usually extraordinarily rapid. In 1918, however, mail carriers who came down with influenza failed to report for duty and the mail was delayed. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

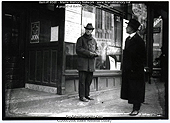

| A man stands in front of a storefront window with posters announcing: Buy WSS; Peace plans have made little progress; Influenza has killed 9,000,000 in three months in entire world; Casualties not reported...at 66,000. [Credit: Maine Historical Society] |

|

Oath-taking ceremony at Camp Meade, Maryland. Camp Meade was the first part of Maryland struck by the pandemic and was also the most devastated by it. [Credit: Library of Congress] |

|

1903. Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland. Johns Hopkins hospital was overwhelmed during the pandemic and lost many of its own nurses and doctors to the flu. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| c1915, Feeding pigeons in Boston Common. The city of Boston was the first in the country to be struck by the pandemic and also suffered the most losses. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

Amusement Parks, such as the Columbia Gardens in Butte, were often closed in the wake of the pandemic. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

The Bureau of Indian Affairs found themselves overwhelmed as influenza swept through the state’s reservations. Influenza swept through rural reservations, killing thousands in its wake. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| c1920. A view of Elm St. in Manchester, New Hampshire. During the pandemic, Manchester imposed tight restrictions on restaurants and other public places. [Credit:The Library of Congress] |

|

1910. A panoramic view of Concord, New Hampshire. In September 1918, the mayor of Concord wrote of the overwhelming number of funerals taking place in the city. [Credit:The Library of Congress] |

|

c1915. Shoppers, tourists and beach-goers stroll the boardwalk in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Following the outbreak, amusement parks, theaters, and other public gathering places were closed indefinitely. [Credit:The Library of Congress] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1912. A panoramic view of the city of Newark, New Jersey in 1912. Newark was the first city in New Jersey to report cases of influenza. [Credit:The Library of Congress] |

|

c.1900. Throngs of people attend the Labor Day Parade on Main St. in Buffalo, New York. During the pandemic, the city limited gatherings of more than 10 people in attempt to limit the spread of the disease. [Credit:The Library of Congress] |

|

c1918. A bird’s eye view of Charlotte, North Carolina looking north, with Camp Greene in the background to the left. On October 24 1918, the city of Charlotte was quarantined. [Credit:The Library of Congress] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| By 1900, an increasing number of physicians were receiving clinical training. This training provided doctors with new insights into disease causation and the nature of specific types of diseases. [Credit: National Library of Medicine] |

|

Days after Philadelphia’s Liberty Loan parade in September 1918, which was attended by 200,000 people, hundreds of cases of influenza were reported. [Credit: Naval Historical Center] |

|

c1910. The entrance to Forbes Field, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. At the height of the pandemic, public gatherings were limited or banned altogether in many cities. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PHS Officers were stationed all over the world in 1918. |

|

Scientists conducted research in laboratories in the early 1900s. [Credit: Office of the Public Health Service Historian] |

|

1918, Because service workers, who frequently came into contact with the public, were at a greater risk of contracting influenza, they often wore masks in attempt to ward off the disease. The masks, however, were ineffective in preventing the spread of influenza. [Credit: National Archives and Records Administration] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Two women stand over a child in bed. |

|

Cities often sponsored Clean-Up Days. Here, Public Health

Service employees clean up San Francisco’s streets in a campaign to eradicate bubonic plague. [Credit: Office of the Public Health Service Historian] |

|

An old cliché maintained that influenza was a wonderful disease as it killed no one but provided doctors with lots of patients. The 1918 pandemic turned this saying on its head. [Credit: National Library of Medicine] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| c1906. Westminster St. in Providence, Rhode Island. Providence was the city hardest his by the pandemic in Rhode Island. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

c1906. Easton’s Beach in Newport, Rhode Island. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

In July, an American soldier said that while influenza caused a heavy fever, it “usually only confines the patient to bed for a few days.” The mutation of the virus changed all that. [Credit: National Library of Medicine] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Farm work was neglected across the state as entire families fell ill. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

Examination of immigrants at Ellis Island. |

|

Traditional funerals, such as this one in 1910, typically included many friends and relatives of the deceased. During the pandemic, fears that mourners could spread influenza led many communities to ban public funerals. [Credit: Office of the Public Health Service Historian] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In Ogden, shown here in a photograph from 1914, city officials prevented anyone from entering the city without a clean bill of health from a doctor. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

December 1916, A group of ‘newsies’ stand outside a bank in Barre, Vermont selling newspapers. Without broad access to radios, the American public relied heavily on newspapers for information. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

c1905. A view of Main St. in Richmond Virginia. Following the onset of the pandemic, state authorities banned public gatherings at churches, schools, and other places that might further spread the illness. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| c1915. A panoramic view of Newport News, Virginia. Newport News was at greater risk during the pandemic as a result of the frequent movement of sailors and soldiers through its ports in wartime. |

|

Desperate for a cure, Washingtonians flooded drugstores such as this People’s Drugstore in Northwest. c. 1901-1921. — Image courtesy of the Library of Congress. |

|

Policemen in Seattle wore masks in the belief that these would protect them from influenza. The masks provided no real protection. c. 1918. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1921. The Mullens children (and some neighbors) ready for school in Charleston, West Virginia. At the height of the pandemic authorities closed schools and other public gathering places to limit the spread of the disease. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

c1920. Striking miners drawing rations, West Virginia. Coal mining regions of the state were especially hard hit by the pandemic. [Credit: The Library of Congress] |

|

The World of Women in 1918 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1918, Camp Jackson, South Carolina. During the epidemic, the camp’s hospital was expanded, allowing it to treat more than 5000 flu victims throughout the time of the crisis. [Credit: The National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C. (NCP 1310) National Museum of Health and Medicine] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|