Curator's Journal: Frank Goodyear on Zaida Ben-Yusuf

Conducting research for the exhibition “Zaida Ben-Yusuf: New York Portrait Photographer” has been a marvelous adventure. As someone who enjoys doing archival research and hunting for “lost” things, this project has more than held my interest over the course of the last five years. At times, it seemed that each week brought new discoveries about her life and photographic career. The exhibition is on view at the National Portrait Gallery until September 1, 2008.

Conducting research for the exhibition “Zaida Ben-Yusuf: New York Portrait Photographer” has been a marvelous adventure. As someone who enjoys doing archival research and hunting for “lost” things, this project has more than held my interest over the course of the last five years. At times, it seemed that each week brought new discoveries about her life and photographic career. The exhibition is on view at the National Portrait Gallery until September 1, 2008.

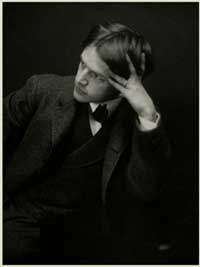

Although I studied the history of photography as a graduate student, I had never encountered Zaida Ben-Yusuf’s name before I saw two prints by her during preparations for an exhibition that the Portrait Gallery opened in 2003. Featuring 100 photographic portraits that had previously been published in the pages of ARTnews, America’s oldest continuously run art magazine, this exhibition included two exquisite portraits by Ben-Yusuf—platinum prints that pictured the sculptor Daniel Chester French and the Ashcan School artist Everett Shinn (below).

I have always been drawn to the beauty of well-crafted platinum prints, and these two photographs became two of my favorite works in the exhibition. Yet when it came time to write something about the pictures for the catalogue, I was struck by the paucity of information about Ben-Yusuf. No one seemed to know for certain when she was born, when she came to America, and what prompted her to pursue photography. At the time, I struggled to write labels for these two prints and ultimately had to dedicate most of my text to the subjects of these portraits.

I have always been drawn to the beauty of well-crafted platinum prints, and these two photographs became two of my favorite works in the exhibition. Yet when it came time to write something about the pictures for the catalogue, I was struck by the paucity of information about Ben-Yusuf. No one seemed to know for certain when she was born, when she came to America, and what prompted her to pursue photography. At the time, I struggled to write labels for these two prints and ultimately had to dedicate most of my text to the subjects of these portraits.

New research technologies such as electronic databases—in particular, Proquest Historical Newspapers, Harpweek, and the American Periodical Series—made much of my early research possible. In searching on these sites, I learned quickly that Ben-Yusuf regularly contributed photographs and essays to magazines and newspapers at the turn of the twentieth century. I also encountered profiles of her written by others.

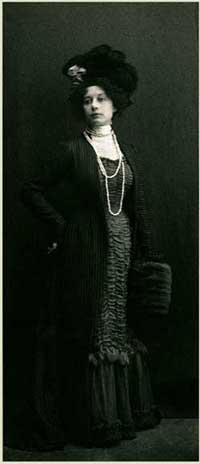

As Zaida Ben-Yusuf (right) is such a distinctive name, records of her contributions—and her mother’s—appeared with remarkable ease in these databases. Perhaps not surprisingly, editors frequently misspelled her name, and it was at times amusing to see how her pictures were credited in newspaper and magazine captions. In an earlier moment—when microfilm was king—it would have been impossible to locate as many different items as I did. Indeed, the recovery of Ben-Yusuf’s life was made possible by these new technologies.

As Zaida Ben-Yusuf (right) is such a distinctive name, records of her contributions—and her mother’s—appeared with remarkable ease in these databases. Perhaps not surprisingly, editors frequently misspelled her name, and it was at times amusing to see how her pictures were credited in newspaper and magazine captions. In an earlier moment—when microfilm was king—it would have been impossible to locate as many different items as I did. Indeed, the recovery of Ben-Yusuf’s life was made possible by these new technologies.

This exhibition and its accompanying catalogue were also made possible because the Smithsonian continues—despite financial pressures—to encourage original scholarship. The receipt in 2004 of a Smithsonian Scholarly Studies grant enabled me to travel to a number of museums, archives, and libraries, where I learned more about Ben-Yusuf and began to encounter more examples of her vintage photographs.

One of the highlights of this travel was a trip to England in 2005 to investigate details about her youth. Although I had read an article prior to my trip that suggested that she was originally from Armenia—and another that indicated she was born in Paris—it was at the Family Records Center in London where I finally unearthed her birth certificate. This document and others provided fascinating insights into her family history and led me to pursue a variety of other research leads. Because a biographer is always interested in knowing more about the character and personality of the subject he or she studies, it was also revealing to learn from her birth certificate that Ben-Yusuf often lied about her age.

Because a museum exhibition is composed of notable objects, I understood early on that I needed to start locating examples of her work, if I wanted to develop anything larger than a scholarly article. A cursory search through photography collections here in Washington and other well-known collections in New York yielded a dozen or so of her pictures. Gathering together a dozen pictures, though, doesn’t constitute an exhibition, so I was compelled to look further afield.

I knew that she was a prominent portrait photographer—who attracted a number of leading actors, writers, artists, and politicians to her studio—because I had encountered reproductions of these pictures in magazines and newspapers. The question then became, where are the vintage prints? Over the last couple of years, I am happy to report that I was able to track down a good number of these photographs—enough to entice Marc Pachter, the Portrait Gallery’s director (now retired), to permit me to develop this project into an exhibition. The results of this adventure are now on view at the Portrait Gallery through September 1, 2008.

Two final thoughts: first, research is not a solitary activity, and I enjoyed the support and expertise of dozens of colleagues and friends. In particular, Beverly Brannan at the Library of Congress—a prominent historian with a special interest in women photographers—shared valuable information, as well as great enthusiasm for Ben-Yusuf’s photography.

And second, I must acknowledge here that I didn’t track down all of the pictures that I hoped to find. There are wonderful portraits that Ben-Yusuf completed of figures such as reformer Jacob Riis, artist William Merritt Chase, actress Julia Marlowe, and critic Sadakichi Hartman that I would give my left arm to find.

My hope is that the exhibition and catalogue will encourage others to continue the search. As such, if you have any questions—or if you know about the whereabouts of any missing pictures by her—please don’t hesitate to write.

-Frank A. Goodyear III

Announcement of an Exhibition of Photographs by Zaida Ben-Yusuf/Zaida Ben-Yusuf,1899/The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mrs. Elizabeth Guy Bullock, accession number SC2006.6

Everett Shinn/Zaida Ben-Yusuf,c 1901/Platinum print/ARTnews Collection

Portrait of Miss Ben-Yusuf/Zaida Ben-Yusuf, 1898/Platinum print/National Museum of American History, Behring Center, Smithsonian Institution

Among the recent acquisitions placed on view at the

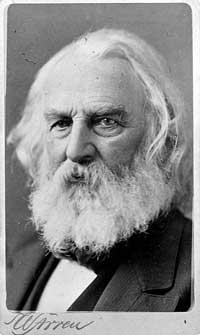

Among the recent acquisitions placed on view at the  Although Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” provides the reader with a wonderfully dramatic setting in which our hero rides out of Boston to warn the colonists in Lexington and Concord of the impending British march, there is a disparity between the poetic narrative and the facts of April 18, 1775. History and Longfellow (right) run pretty much parallel until Revere rides into Lexington. Longfellow writes:

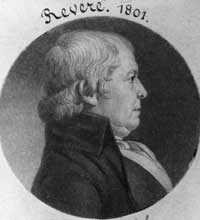

Although Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” provides the reader with a wonderfully dramatic setting in which our hero rides out of Boston to warn the colonists in Lexington and Concord of the impending British march, there is a disparity between the poetic narrative and the facts of April 18, 1775. History and Longfellow (right) run pretty much parallel until Revere rides into Lexington. Longfellow writes: So, other than the fictitious account of Paul Revere’s ride handed down to us by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, why do we hold Revere in such acclaim? “Paul Revere is sometimes underestimated,” says Patrick Leehey, research director for the

So, other than the fictitious account of Paul Revere’s ride handed down to us by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, why do we hold Revere in such acclaim? “Paul Revere is sometimes underestimated,” says Patrick Leehey, research director for the  April is

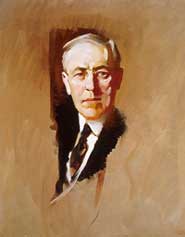

April is  April 15 connotes a day of great civic participation in American government; it is the day, of course, income taxes come due as stipulated by the 16th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1913 during the presidency of Woodrow Wilson.

April 15 connotes a day of great civic participation in American government; it is the day, of course, income taxes come due as stipulated by the 16th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1913 during the presidency of Woodrow Wilson.  Of tragic note on this date, Abraham Lincoln died at 7:22 in the morning of April 15, 1865, after having been shot by the actor and southern fire-eater John Wilkes Booth on the previous evening. On the night of the 14th, Lincoln and his wife had gone to Ford’s Theatre to see a production of Our American Cousin with the actress Laura Keene as the main attraction.

Of tragic note on this date, Abraham Lincoln died at 7:22 in the morning of April 15, 1865, after having been shot by the actor and southern fire-eater John Wilkes Booth on the previous evening. On the night of the 14th, Lincoln and his wife had gone to Ford’s Theatre to see a production of Our American Cousin with the actress Laura Keene as the main attraction.  In the pandemonium that followed, Booth escaped, despite having broken his leg when landing on stage. When Lincoln died, allegedly Edwin Stanton uttered the phrase, “Now he belongs to the ages.” Booth was tracked into southern Maryland and shot to death on April 26.

In the pandemonium that followed, Booth escaped, despite having broken his leg when landing on stage. When Lincoln died, allegedly Edwin Stanton uttered the phrase, “Now he belongs to the ages.” Booth was tracked into southern Maryland and shot to death on April 26.

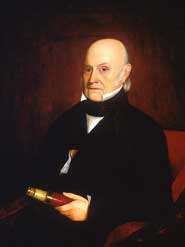

Not often on view because of the fragility of the pastel medium is NPG’s portrait of John Quincy Adams (1767–1848), executed by the German artist Izaac Schmidt in July 1783. The National Portrait Gallery has many other representations of Adams—showing him as a diplomat, as the sixth president of the United States, and especially as “Old Man Eloquent” of the House of Representatives—but this small drawing, done during the month in which Adams turned sixteen, has the distinction of being his earliest known likeness.

Not often on view because of the fragility of the pastel medium is NPG’s portrait of John Quincy Adams (1767–1848), executed by the German artist Izaac Schmidt in July 1783. The National Portrait Gallery has many other representations of Adams—showing him as a diplomat, as the sixth president of the United States, and especially as “Old Man Eloquent” of the House of Representatives—but this small drawing, done during the month in which Adams turned sixteen, has the distinction of being his earliest known likeness. Adams gave the original portrait to his sister Nabby, and later had a copy made for his wife Louisa Catherine, pointing out that he appeared in his “best coat and powdered hair.” When he was sixty-four (the age the Beatles sang about), Adams, contemplating his young self, observed, “And they who look at the bald head, the watery eye, and the wrinkled brow of this day, would search in vain for the strong likeness which it was said to exhibit when it was taken.”

Adams gave the original portrait to his sister Nabby, and later had a copy made for his wife Louisa Catherine, pointing out that he appeared in his “best coat and powdered hair.” When he was sixty-four (the age the Beatles sang about), Adams, contemplating his young self, observed, “And they who look at the bald head, the watery eye, and the wrinkled brow of this day, would search in vain for the strong likeness which it was said to exhibit when it was taken.” April 10, 2008, marked the eighty-third anniversary of the publication of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, considered by many critics to be the greatest American novel. Interestingly, although most students of American literature over the past half-century will attest to having read Gatsby, it was not nearly as popular in its own day.

April 10, 2008, marked the eighty-third anniversary of the publication of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, considered by many critics to be the greatest American novel. Interestingly, although most students of American literature over the past half-century will attest to having read Gatsby, it was not nearly as popular in its own day.

Forty years ago, on April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. As one of the founders and the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Dr. King worked from the 1950s until his death as a proponent of nonviolent civil change. In his autobiography he states, “All my adult life I have deplored violence and war as instruments for achieving solutions to mankind’s problems. I am firmly committed to the creative power of nonviolence as the force which is capable of winning lasting and meaningful brotherhood and peace.”

Forty years ago, on April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. As one of the founders and the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Dr. King worked from the 1950s until his death as a proponent of nonviolent civil change. In his autobiography he states, “All my adult life I have deplored violence and war as instruments for achieving solutions to mankind’s problems. I am firmly committed to the creative power of nonviolence as the force which is capable of winning lasting and meaningful brotherhood and peace.”

Recent Comments