|

Insecticide-Treated Bed Nets

|

A Nigerian

woman and her baby show their insecticide-treated bed

net. (Courtesy The Carter Center/E. Staub) |

Insecticide-treated

bednets (ITNs) decrease death and disease due to malaria,

and their mass distribution to children under five and to pregnant

women is now a major

intervention against malaria in Africa.

However, the distribution of ITNs can be costly and difficult

to organize, and these issues can prevent them from getting

to the remote populations who need them most. Public health

workers have improved coverage of ITNs by linking their distribution

with campaigns against other health problems such as measles,

polio, and intestinal worms. Recent experience in Nigeria

shows successful linkage with yet another disease, lymphatic

filariasis.

Lymphatic Filariasis

|

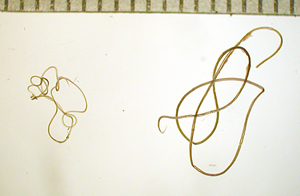

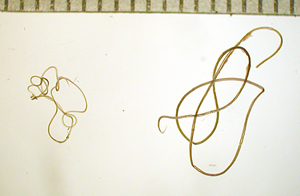

Wuchereria

bancrofti is the main agent of lymphatic filariasis

in Nigeria. Adult worms (shown here) clog and destroy

the lymphatic drainage system, leading to elephantiasis.

Female worms (right) measure up to 4 inches, while

males (left) are smaller. (CDC photo) |

Lymphatic

filariasis (LF), a parasitic infection transmitted by mosquitoes,

affects over 120 million people in more than 80

countries. The adult female worms generate young worms

(microfilariae),

which circulate in the blood and which, when picked up by

a mosquito, can result in the infection of another person.

LF is a leading cause of disability worldwide. The adult worms

live for years in the infected person’s lymphatic system, which

they clog and damage. This process can result in lymphedema and elephantiasis,

an incapacitating swelling in the legs, genital organs, or arms. The

affected parts are often secondarily infected by bacteria,

and the disease may persist a lifetime.

Global Campaign to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis

Following a 1993 report by the Carter

Center's International Task Force for Disease Eradication, the World

Health Organization in 1997 called for the elimination of LF.

This task is currently

|

A

woman in Nigeria washes her left leg and foot, swollen

by lymphatic filariasis; more

advanced cases can be very

crippling; frequent washing with soap and water helps

prevent bacterial superinfection. (Courtesy The Carter

Center/F. Richards) |

coordinated by the Global

Alliance to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis. The alliance’s

strategy is to interrupt the transmission of LF by eliminating

the microfilariae through annual mass drug administration

(MDA), and to alleviate and prevent suffering caused by the disease.

MDAs aim to administer to entire populations in the affected areas

a single oral dose of diethylcarbamazine or ivermectin (Mectizan®,

donated by Merck & Co’s Mectizan

Donation Program)* combined with albendazole (donated by GlaxoSmithKline’s Global

Community Partnerships Lymphatic Filariasis Program).* The drugs

are not given to young children or to pregnant women.

Joining Efforts in Nigeria

In Africa, LF and malaria often occur in the same locales and are

transmitted by the same mosquitoes. Combining the health interventions

directed against these two diseases into a single bundle may prove beneficial.

Sharing the resources may reduce costs, and protection from the mosquito

vectors may reduce transmission of both diseases.

This is particularly

true when considering that children under five and pregnant

women do not receive the drugs during MDA campaigns but are the target

groups for receiving ITNs. Since 2000, the ministries of health of two

states in central Nigeria (Plateau and Nasarawa states), assisted by

the Nigerian Federal ministry of health, the

Carter Center’s Lymphatic Filariasis Program, and CDC, have

organized yearly MDAs to eliminate LF. These have evolved into

well-established systems for drug distribution, with more than 3.2 million

persons treated in 2004.

Going one step further, the states’ LF and malaria programs

developed a collaboration to fight both diseases simultaneously,

by piggybacking to the MDA campaign the distribution of ITNs

donated by the Roll

Back Malaria Partnership. In two demonstration districts, Kanke

and Akwanga (combined population approximately 218,000), the

two programs developed logistical systems, trained distributors,

and educated local communities in how to use ITNs.

Results

During a three-month period (July-September 2004), 38,600 ITNs were

distributed in 159 villages,

free of charge to children under five and

pregnant women, during the MDA process. About 148,000 persons

were treated with medicines for LF at the same time.

|

Children

under five and pregnant women do not receive drugs against

lymphatic filariasis, but insecticide-treated bed nets

can protect them against both filariasis and malaria. (Courtesy

The Carter Center/A. Eigege) |

Preliminary data from an evaluation conducted eight months later showed

a nine-fold increase in ITN ownership among households with

a child under five or a pregnant woman, from 9 percent before

the distribution to 80 percent afterwards. The drug coverage for LF remained

as high as in years past (68 percent). Thus, the MDA rapidly

helped the malaria program reach high ITN coverage without adversely affecting

the drug distribution. This successful pilot strengthens findings from

other combined

health campaigns that ITN distribution can be successfully piggybacked

onto other health interventions. It shows, more specifically,

how two programs fighting two severe mosquito-borne diseases

can share their resources to achieve their goals faster, better, and

more cheaply.

This article contributed by the The

Carter Center.

* Drug brand names and manufacturers are mentioned for informational

purposes only and do not imply endorsement by CDC, the U.S.

Public Health Service, or the U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services.

Page last modified : August

18,

2005

Content source: Division of Parasitic Diseases

National Center for Zoonotic, Vector-Borne, and Enteric Diseases (ZVED)

|

|

|