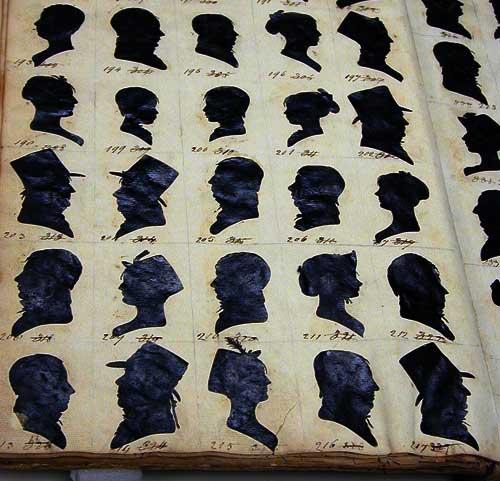

In the 1920s, Alice Van Leer Carrick, the pioneering authority on American silhouettes, came upon an album kept by William Bache (1771–1845) as a record of his work and expressed her delight in “turning the pages of this century-old treasure-trove of nearly two thousand shadow portraits.”

There she found images of Chancellor George Wythe, President Thomas Jefferson, and Secretary of State Edmund Randolph, as well as “hundreds of other profiles of everyday people, less well-known, but equally well cut; all of them vivid and interesting.” This duplicate book of 1,846 images, which had long remained in the hands of Bache descendants, came to the attention of the National Portrait Gallery’s Curator of Prints and Drawings Wendy Wick Reaves and was acquired in 2001.

Research on Bache—first heard from with his patented physiognotrace (a profiletracing apparatus) at Baltimore in 1803 and who subsequently traveled to Virginia, New Orleans, Cuba, and New England—is ongoing. Research on the scores of men, women, and children who seized the opportunity to have their shadows cut is also under way, and many of them have stories evocative of the era in which they lived.

Bache identifies number 361 in the album as “Col Butler"(shown on right): Thomas Butler, a Revolutionary War soldier and Indian fighter, and an officer in the U.S. Army. He was—when he gave up a few minutes of his time and one dollar to secure “four correct likenesses” of himself from Bache—in trouble because he refused to cut his hair and give up his queue.

Bache identifies number 361 in the album as “Col Butler"(shown on right): Thomas Butler, a Revolutionary War soldier and Indian fighter, and an officer in the U.S. Army. He was—when he gave up a few minutes of his time and one dollar to secure “four correct likenesses” of himself from Bache—in trouble because he refused to cut his hair and give up his queue.

On April 30, 1801, the commanding general of the army, James Wilkinson (Bache number 216), had issued an order requiring all military men to crop their hair, and Butler was among the many conservative officers who chose to ignore a decree that not only infringed on personal preference but also carried with it an association with the radicals of the French Revolution.

Butler, a law student before he became a professional soldier, pronounced the order “impertinent, arbitrary and illegal.” He was court-martialed in 1803, found guilty, and reprimanded. When he was subsequently transferred to New Orleans, General Wilkinson hoped that, in the interest of preventing “trouble, perplexity and further injury to the service,” Butler would “leave his tail behind him.”

Butler arrived in New Orleans on October 4, 1804, his pigtail intact. He was arrested and in February formally charged with “willful, obstinate and continual disobedience.” An indignant Butler continued to insist that he considered the order to crop his hair “an arbitrary infraction of my natural rights.”

A military tribunal was convened on July 1, 1805, and from St. Louis, Wilkinson instructed the commanding general at New Orleans to make those who would sit in judgment of Butler aware “that the President of the United States, without any public expression, has thought proper to adopt our fashion of the hair cropping.” (Bache shows Jefferson in 1804 with a dangling queue.)

On September 7, while awaiting the final outcome of his trial, Butler died at his nephew’s plantation a few miles above New Orleans. He told his friends he wanted his queue displayed at his funeral. “Bore a hole through the bottom of my coffin right under my head,” he directed, “and let my queue hang

through it,—that the d---d old rascal [Wilkinson] may see that, even when dead, I refuse to obey his orders.” There was no evidence that this was done, but thanks to William Bache, Butler’s pigtail has remained in full view down through the ages.

Various Sitters/Ledger book of William Bache, with associated pieces, c. 1803-1812/National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; partial gift of Sarah Bache Bloise

Recent Comments