skip

navigation  |

800-411-3222 (Español)

Manures for Organic Crop Production |

| By George

Kuepper NCAT Agriculture Specialist ©2003 NCAT ATTRA Publication #IP127 |

The

printable PDF version of the entire document is available

at: http://attra.ncat.org/attra-pub/PDF/manures.pdf 12 pages — 385K Download Acrobat Reader |

AbstractLivestock manures are an important resource in sustainable and organic crop production. This publication addresses the problems and challenges of using both raw and composted manures and discusses some of the solutions. It also deals with guano, a similar material. Table of Contents

IntroductionLivestock manure is traditionally a key fertilizer in organic and sustainable soil management. It is most effectively used in combination with other sustainable practices. These include crop rotation, cover cropping, green manuring, liming, and the addition of other natural or biologically friendly fertilizers and amendments. In organic production, manure is commonly applied to the field in either a raw (fresh or dried) or composted state. This publication addresses the advantages and constraints of using manure in either form, but with particular focus on raw manure; it does not discuss the specific circumstances and challenges associated with handling and applying slurry manure. There are clear restrictions on the use of raw manure in organic farming. These restrictions are detailed in the National Organic Program (NOP) Regulations, which constitute the federal standard for organic production. Details will be discussed later in this publication. Raw Manure Use: Problems and SolutionsRaw manure is an excellent resource for organic crop production. It supplies nutrients and organic matter, stimulating the biological processes in the soil that help to build fertility. Still, a number of cautions and restrictions are in order, based on concerns about produce quality, food contamination, soil fertility imbalances, weed problems, and pollution hazards. ContaminationSome manures may contain contaminants such as residual hormones, antibiotics, pesticides, disease organisms, and other undesirable substances. Since many of these can be eliminated through high-temperature aerobic composting, this practice is recommended where low levels of organic contaminants may be present. Caution is advised, however, as research has demonstrated that Salmonella and E. coli bacteria appear to survive the composting process much better than previously thought. (1) The possibility of transmitting human diseases discourages the use of fresh manures (and even some composts) as preplant or sidedress fertilizers on vegetable crops—especially crops that are commonly eaten raw. (2) Washington State University (3) suggests that growers:

In February 2000, the issue of manure use on organic farms was highlighted on the television news program 20/20. The segment suggested that fertilization with livestock manures made organic foods more dangerous than other food products in the marketplace. (4) The show's producers arranged for a sampling of various organic and nonorganic vegetables from store shelves and tested for the presence of E. coli. The samples of both organic and nonorganic produce were generally free of serious contamination. The exceptions were bagged sprouts and mesclun salad mix. Of these, more E. coli contamination was observed on the organic samples. It was largely on this basis that the news program challenged organic farming. The attack was embarrassing to the organic industry and forced its membership to undertake a lot of "damage control," despite the fact that the allegations were contrived and based on poor science. The sampling was not statistically significant (i.e., the same sampling done today might produce the opposite result). The show failed to point out that the specific test used does not distinguish between pathogenic and benign forms of E. coli. Also ignored was the obvious fact that conventional farmers use manure, too! Furthermore, the reporter failed to disclose the vested interests of the individual bringing the charges (Dennis Avery of the Hudson Institute—a "think tank" heavily funded by conventional agriculture interests), presenting him instead as a former official with the Agriculture Department. (5) John Stossel—the journalist responsible for the 20/20 report—subsequently issued an apology and a correction. (6) Unlike conventional farmers, who have only safety guidelines regarding manure use, certified organic farmers must follow stringent protocols. Raw manure may NOT be applied to food crops within 120 days of harvest where edible portions have soil contact (i.e., most vegetables, strawberries, etc.); it may NOT be applied to food crops within 90 days of harvest where edible portions do not have soil contact (i.e., grain crops, most tree fruits). Such restrictions do not apply to feed and fiber crops. (7) Organic substances are not the only contaminants found in livestock manures. Heavy metals can be a problem, especially where industrial-scale production systems are used. Concerns over heavy-metal and other chemical contamination have dogged the use of poultry litter as an organically acceptable fertilizer in Arkansas, where it's readily and cheaply available. (8) This matter is discussed in more detail under "Composted Manures." Heavy-metal contamination is also a concern with composted sewage sludge (biosolids)—a major reason for its being prohibited from certified organic production. Under federal organic standards, certifiers may require testing of manure or compost if there is reason to suspect high levels of contamination. Produce Quality ConcernsIt has long been acknowledged that improper use of raw manure can adversely affect the quality of such vegetable crops as potatoes, cucumbers, squash, turnips, cauliflower, cabbage, broccoli, and kale. As it breaks down in the soil, manure releases chemical compounds such as skatole, indole, and other phenols. When absorbed by the growing plants, these compounds can impart off-flavors and odors to the vegetables. (9) For this reason, raw manure should not be directly applied to vegetable crops; it should instead be spread on cover crops planted the previous season. In the Ozark region, for example, poultry manure is sometimes used to fertilize winter cover crops that will be incorporated ahead of spring vegetable planting. Fertility ImbalancesRaw manure use has often been associated with imbalances in soil fertility. There are several causal factors:

To avoid manure-induced imbalances, continually monitor soil fertility, using appropriate soil tests. Then apply lime or other supplementary fertilizers and amendments to ensure soil balance, or restrict application levels if needed. A soil audit that measures cation base saturation is strongly advised. If this service is not provided through your state's Cooperative Extension Service, use of a private lab is suggested (see the ATTRA publication Alternative Soil Testing Laboratories for a listing). Understanding the soil's needs is only part of the equation. You must also know the nutrient content of the manure you're applying. Standard fertilizer values (such as those shown in Table 1) should be used only for crude approximations. The precise nutrient content of any manure is dependent not only on livestock species, but also on the ration fed, the kind of bedding used, amount of liquid added, and the kind of capture and handling system employed. Also, some traditional assumptions about manure composition may need to be updated. Because of the abundance of sulfur in rations, manure has long been recognized as a good source of sulfur. However, less sulfur is applied to crops in contemporary high-analysis fertilizers, and atmospheric deposition has been decreased by pollution controls. Sulfur deficiencies are appearing in many soils, and levels in manure may also be diminished. (9) It is advisable to test manure as you would test the soil, in order to assess its fertilizer value.

Cooperative Extension is an excellent source of guides to manure use. These are often tailored to the region and provide useful information not mentioned in more general publications. Weed ProblemsUse of raw manures has often been associated with increased weed problems. Some manure contains weed seed, often from bedding materials like small-grain straw and old hay. High-temperature aerobic composting can greatly reduce the number of viable weed seeds. (12) In many cases, however, the lush growth of weeds that follows manuring does not result from weed seeds in the manure, but from the stimulating effect manure has on seeds already present in the soil (as demonstrated through studies at Auburn University using broiler litter). (13) The flush of weeds may result from enhanced biological activity, the presence of organic acids, an excess of nitrates, or some other change in the fertility status of the soil. Depending on the weed species that emerge, the problem may be related to the sort of fertility imbalances described above. Excesses of potash and nitrogen in particular can encourage weeds. (9) Monitor the nutrient contents of soil and manure and spread manure evenly to reduce the incidence of weed problems. PollutionWhen the nutrients in raw or composted manure are eroded or leached from farm fields or holding areas, they present a potential pollution problem, in addition to being a resource lost to the farmer. Leached into groundwater, nitrates from manure and fertilizers have been linked to a number of human health problems. Flushed into surface waters, nutrients can cause eutrophication of ponds, lakes, and streams. Excess nitrates from farms and feedlots in the Mississippi Basin are deemed the primary cause of the Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone—a hypoxic (oxygen deprived) area about the size of New Jersey that now threatens the shrimp, fishing, and recreational industries off the Louisiana and Texas coasts. (14) The manner in which manure is collected and stored prior to field use affects the stabilization and conservation of valuable nutrients and organic matter. Composting is one means of good manure handling and is discussed in more detail below. Reducing manure run-off and leaching losses from fields is a matter of both volume and timing. Manure application far in excess of crop needs greatly increases the chances of nutrient loss, especially in high-rainfall areas. Manure spread on bare, frozen or erodible ground is subject to run-off, especially where heavy winter rains are common. Under some conditions, however, winter-applied manure can actually slow run-off and erosion losses from fields, likely by acting as a light organic mulch. (15) Sheet-composting manure (tilling it into the soil shortly after spreading) or applying it to growing cover crops are two advisable means of conserving manure nutrients. Grass cover crops, such as rye and ryegrass, are especially good as "catch crops"—cover crops grown to absorb soluble nutrients from the soil profile to prevent them from leaching. (All cover crops function as catch crops to a greater or lesser degree.) It is a sound strategy, therefore, to apply manure to growing catch crops or just prior to planting them. Note that both sheet composting and applying to cover crops have trade-offs. Sheet composting improves the capture of ammonia nitrogen from manure, but requires tillage, which leaves the soil bare and vulnerable to erosion and leaching losses. Surface-applying to cover crops (with no soil-incorporation) eliminates most leaching and erosion losses but increases ammonia losses to the atmosphere. More details on these trade-offs will be provided below in the section Field-applying Manures and Composts. Composted ManuresAn effective composting process converts animal wastes, bedding, and other raw products into humus—the relatively stable, nutrient-rich, and chemically active organic fraction found in fertile soil. In stable humus, there is practically no free ammonia or soluble nitrate, but a large amount of nitrogen is tied up as proteins, amino acids, and other biological components. Other nutrients are stabilized in compost as well. Composting livestock manure reduces many of the drawbacks associated with raw manure use. Good compost is a "safe" fertilizer. Low in soluble salts, it doesn't "burn" plants. It's also less likely to cause nutrient imbalances. It can safely be applied directly to growing vegetable crops. Many commercially available organic fertilizers are based on composted animal manures supplemented with rock powders, plant by-products like alfalfa meal, and additional animal by-products like blood, bone, and feather meals. The quality of compost depends on the feedstuffs used to make it. Unless it is supplemented in some way, composted broiler litter—though more stable than raw litter—will be abundant in phosphates and low in calcium. Continued applications may lead to imbalanced soil conditions in the long term, as with some raw manures. Soil and compost testing to monitor nutrient levels is strongly advised. While composting can degrade many organic contaminants, it cannot eliminate heavy metals. In fact, composting concentrates metals, making the contaminated compost, pound for pound, more potentially hazardous than the manure it was created from. Broiler litter and broiler litter composts have been restricted from certified organic production in the mid-South largely for this reason. Arsenic—once used in chicken feed as an appetite stimulant and antibiotic—was a particular concern. Since the precise composition of commercial livestock feeds is proprietary information, arsenic may still be an additive in formulations in some regions. (16) A more recent concern is the inclusion of additional copper in poultry diets and its accumulation in the excreted manure. While copper is an essential plant nutrient, an excessive level in the soil is toxic. This concern is most relevant to organic horticultural producers, who often apply significant amounts of copper as fungicides and bactericides, increasing the hazard of buildup in the soil. Whenever you import large amounts of either composted or raw manure onto the farm, it is wise to inquire about the feeding practices at the source or have the material tested. The NOP has put no specific restrictions on when farmers can apply composted manure to crops; however, it is very specific about manure composting procedures. According to the NOP Regulations, compost must meet the following criteria:

The National Organic Standards Board—the advisory body to the NOP—has recommended a more flexible interpretation of the compost rules, but this has not yet been incorporated into the legislation. (18) ATTRA offers information on various composting methods in the publications Farm-Scale Composting Resource List, Worms for Composting (Vermicomposting), and Biodynamic Farming and Compost Preparation. We can also provide information on the more exacting processes of controlled microbial composting (also known as CMC or Luebke composting). About GuanoGuano is the dried excrement of various species of bats and seabirds. It has a long history of use as an agricultural fertilizer. It was apparently highly prized by native Peruvians well before the Spanish conquest. Before the development of chemical fertilizers, there was U.S. Government support for entrepreneurs who discovered and developed guano deposits. (19, 20) The nutrient content of commercial guano products can vary considerably based on the diet of the birds or bats. Seabirds subsist largely on fish; depending on the species, bats may thrive largely on insects or on fruits. Another major factor is the age of the source deposit. Guano products may be fresh, semi-fossilized, or fossilized. (21) A quick check of several commercial products provided the range of analyses shown in Table 2.

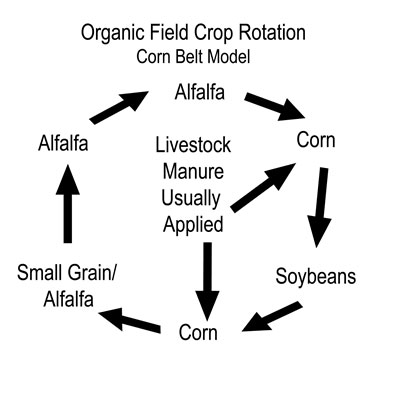

As a nutrient source, guano is considered to be moderately available, as are most manures. (24) One source (20) suggests that guanos are rich in "bioremediation microbes" that assist in cleaning up soil toxins. If true, this would make guano an excellent amendment to use when transitioning from conventional to more sustainable production systems. ATTRA, however, has not reviewed the documentation to substantiate this claim. Guano is advertised as being quite safe and non-burning to plants; "foolproof" is the term sometimes employed. There does not appear to be any evidence to the contrary. There is, however, one serious human illness connected with guano. Histoplasmosis, caused by the fungus Histoplasm capsulatum, produces symptoms similar to influenza in mild cases, or pneumonia when severe. In persons with compromised immune systems, histoplasmosis can produce complications leading to death. (25, 26, 27) Accumulations of both bird and bat guano can contain the Histoplasm spores, as can manure from old poultry houses. The problems are most severe in piles that have aged for two or more years, as the fungus has additional time to proliferate and produce spores. In a fresh state, bat guano is more hazardous than bird guano because infected bats can "shed" the organism and rapidly inoculate the manure. (27) It appears that those who spend time in caves, and those who harvest and package guano, are at the greatest risk of infection. Cases of infection through later handling are apparently not common, though if they have occurred, they may well have been misdiagnosed as influenza or a similar ailment. Infections come about when dust and other aerosols bearing the fungal spores are inhaled. Therefore respirators and masks are recommended when handling guanos. Also, clothing should be removed carefully afterwards to avoid inhaling accumulated dusts. If possible, wet down the pile of dried guano to reduce dust. (25, 26, 27) At the present time, the NOP regulations treat guano as raw, uncomposted manure. It is therefore subject to the same 90- and 120-day application restrictions. It is relatively safe but rather expensive for organic production. Its use is best justified on high-value crops. Field-applying Manures and CompostsWhen . . .The 90- and 120-day restrictions on manure application are mainly intended to prevent food contamination with manure pathogens. Beyond these timing constraints, however, additional agronomic considerations are involved in scheduling manure applications. Generally, manures and composts have their strongest effect on a crop or cover crop if applied just in advance of planting. Growers of agronomic crops commonly apply them to the most nitrogen-hungry and responsive crops. In midwestern organic rotations (see Figure 1), this would likely be corn. While the small-grain crop shown here would respond positively to manure, it is a relatively low-value crop and therefore resides at the bottom of the pecking order when manure resources are in short supply.

The circumstances are a bit more complex with vegetable crops. According to experienced market gardener and author Eliot Coleman (28), crops like squash, corn, peas, and beans do best when manure is spread and incorporated just prior to planting. The same holds true for leafy greens, though only well-composted manure should be used. Cabbages, tomatoes, potatoes and root crops, on the other hand, tend to do better when the ground has been manured the previous year. Obviously, crop rotations that feature non-manured crops following manured crops would be ideal. To achieve maximum recovery of the nutrients in spread manure, sheet composting—plowing or otherwise incorporating the manure into the soil as soon as possible after spreading—is the best option. Research has shown that solid raw manure will lose about 21% of its nitrogen to the atmosphere if spread and left for four days; prompt soil incorporation reduces that loss to only 5%. (10) However, since excessive tillage is discouraged in sustainable systems, options for sheet composting may be limited on some farms. The next-best option appears to be spreading onto growing cover crops. This reduces the chances of loss through surface erosion and cuts leaching significantly. However, it does little to control ammonia losses to the atmosphere. How . . .One of the weakest links in the use of manure as a fertilizer appears to be the actual process of field spreading. According to some researchers, the conventional box spreader is an "engineering anachronism"—an outdated piece of equipment designed principally to dispose of a waste product, not to manage a nutrient resource. Many machines are built to "dump" as much material as possible in a short time and are difficult to calibrate if you want to distribute manure accurately and according to crop needs. (29) (Instructions for calibrating compost and manure spreaders are provided in Table 3.) Still, the basic box spreader is the only technology available and affordable to most farmers.

Characteristics to consider when purchasing a spreader (used or new) include:

Box manure spreaders are poor compost spreaders—especially when well-made granular composts are used. Well-made compost is fine, relatively flowable, and is better handled with spreaders suited to broadcasting lime and bulk granular fertilizer. This equipment is much easier to calibrate and provides a more uniform distribution of material. (32) Application rate recommendations for guano are usually provided by the supplier. These rates appear somewhat lower than those for other dried manures. (21) As the cost of guano is relatively high compared to livestock manures, much lower application rates are advised. Apparently, there is also some use of guano as a base for fertilizer "tea." SummaryBoth raw and composted manures are useful in organic crop production. Used properly, with attention to balancing soil fertility, manures can supplant all or most needs for purchased fertilizer, especially when combined with a whole-system fertility plan that includes crop rotation and cover cropping with nitrogen-fixing legumes. The grower needs to monitor nutrients in the soil via soil testing, and learn the characteristics of the manure and/or compost to be used. The grower can then adjust the rates and select additional fertilizers and amendments accordingly. References

Recommended ResourcesThe August 2000 issue of Acres USA features four articles on bats

and guano: The March 2002 issue of Acres USA includes the following article: Back issues of Acres USA are available from: Acres

USA Anon. 2001. Fair price for neighbor's manure? New England Farmer. November. p. LP. Anon. 2001. Manure Management in Organic Farming Systems. Soil Association. July. Available online from the website www.soilassociation.org. Goldstien, Jerome. 1998. Composting for Manure Management. JG Press, Emmaus, PA. 77 p. Available for $39 postage paid from: Biocycle Miles, Carol, Tanya Cheeke, and Tamera Flores. 1999. From End to Beginning: A Manure Resource Guide for Farmers and Gardeners in Western Washington. King County Agricultural Commission, Seattle, WA. 25 p. http://agsyst.wsu.edu/manure.html. Miller, Laura. 2000. Basics of manure management. Small Farm Today. July. p. 28-30. Organic Trade Association. No date. Manure Use and Agricultural Practices. Organic Trade Association, Greenfield, MA. www.ota.com Patriquin, David G. 2000. Reducing risks from E. coli 0157 on the organic farm. Canadian Organic Growers. www.cog.ca/efgsummer2000.htm Pederson, Laura. 1998. Prevent pathogens. American Agriculturist. May. p. 26. Manures for Organic Crop Production

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Site Map | Comments | Disclaimer | Privacy Policy | Webmaster Copyright © NCAT 1997-2009. All Rights Reserved. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||