GAO: Working for Good Government Since 1921

| Return to Table of Contents | < Previous Chapter | Next Chapter > |

Chapter 2, John R. McCarl: A Tenacious Financial Watchdog, 1921-1936

From 1921 until the end of World War II in 1945, GAO concentrated on examining the legality and adequacy of government expenditures. This legalistic approach reflected late 19th century and early 20th century views of auditing, which focused on a careful review of fiscal records. The work was done centrally, which meant that government agencies had to send their fiscal records to GAO. The first Comptroller General, lawyer John R. McCarl, stated in his annual report for 1926 that "the question whether any particular expenditure or collection is in accordance with law is the principal function of the General Accounting Office."

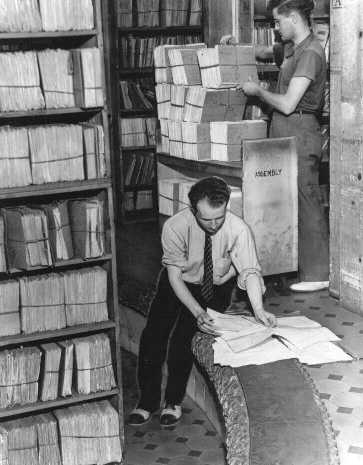

Photo (c) 1940, The Washington Post. Reprinted with permission.

Photo (c) 1940, The Washington Post. Reprinted with permission.

Much of GAO's work during its early years centered on checking vouchers and settling the accounts of executive branch disbursing officers. Departments and agencies sent their vouchers to GAO, which used them to check the legality, propriety and accuracy of expenditures. Examination of the vouchers and supporting documents allowed GAO to look at appropriations charged, obligations incurred, articles purchased or services procured, evidence of receipt, approval by appropriate agency officials, and methods of payment. The photograph shows GAO's clerks examining vouchers in 1940.

Most of GAO's voucher checking was done as post-audits, with departmental disbursing officers sending forms to GAO after they made payments. However, McCarl preferred pre-audits, in which agencies sent vouchers to GAO for audit before payment. Under the pre-audit system, GAO examined vouchers for proposed expenditures and certified the amounts for payment. The pre-audit system enabled disbursing officers to make payments without wondering whether the paid vouchers would clear when sent back to GAO for final settlement.

Although McCarl found a pre-audit system to be more economical and efficient than a post-audit, he knew it depended on a larger number of employees than he had on hand. Consequently, GAO only did selective pre-auditing during McCarl's tenure, and essentially abandoned the process after he left office. Government spending increased so greatly during the 1930s and 1940s, it was impossible for GAO to keep up a meaningful pre-audit effort.

At the time McCarl was Comptroller General, the government relied on a warrant system, under which GAO reviewed requisitions for advances of funds. It forwarded approved requisitions to the Department of the Treasury. The Secretary of the Treasury then signed warrants which were countersigned by the Comptroller General. The warrant system remained in effect until 1950, when the Budget and Accounting Procedures Act authorized the Comptroller General and the Secretary of the Treasury to waive the issuance and countersigning of warrants.

GAO's other activities included receiving copies of cancelled government checks, which it reconciled against the depositary accounts of fiscal agents; issuing decisions on payment questions; helping to process financial claims for and against the government; and prescribing accounting forms and systems. The Pension Building, now home to the National Building Museum, served as GAO's headquarters from 1926 to 1951.

GAO's clerks at work in the Great Hall of the Pension Building in the 1920s

GAO's workload increased in the 1930s, as federal money poured into "New Deal" recovery and relief efforts to combat the Great Depression during President Franklin D. Roosevelt's administration. GAO, which started out in 1921 with about 1,700 employees, soon found itself shorthanded and had to hire more employees to process the growing pile of vouchers. By 1939, its workforce numbered nearly 5,000. Although Washington remained the center of GAO's activities, the agency's auditors first began doing fieldwork in the mid-1930s. During the Roosevelt administration, they looked at government agriculture programs in Kentucky and several southern states.

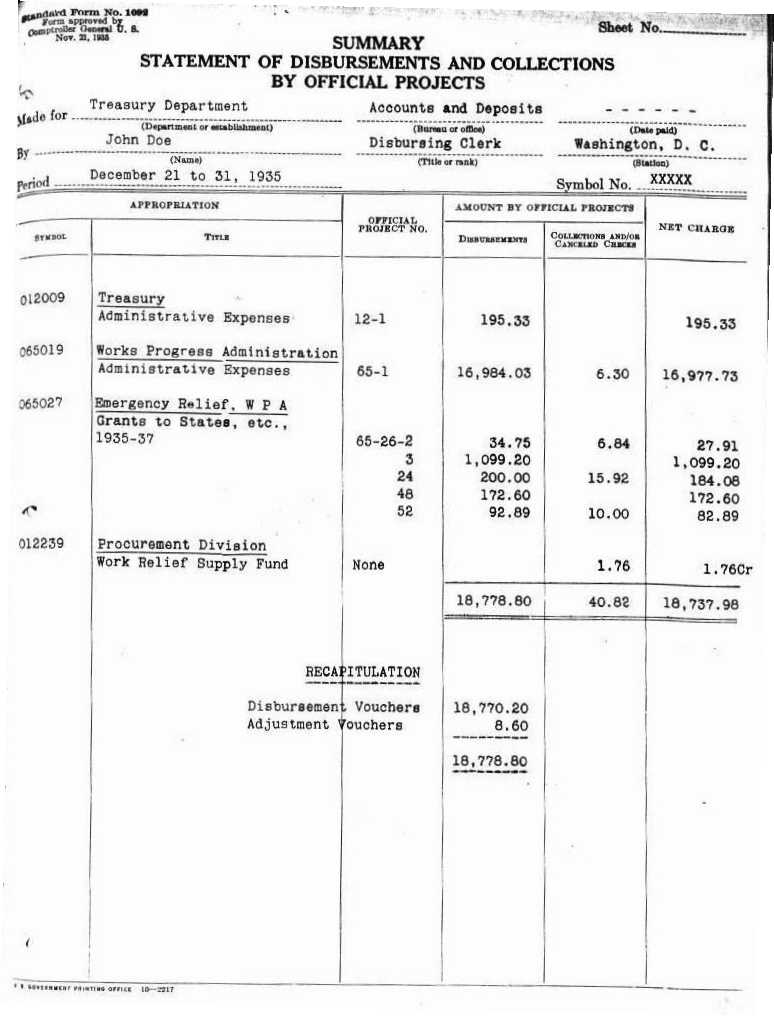

The Comptroller General approved forms, such as the one shown above, for executive agencies to use in recording disbursements and collections. The New Deal-era Works Progress Administration was in charge of construction, arts, and education projects aimed at fighting the Great Depression.

Comptroller General McCarl often clashed with the executive branch in his decisions on government expenditures, in which he tended to adhere strictly to the letter of the law. He disallowed some of President Roosevelt's New Deal spending efforts and was involved in jurisdictional conflicts with the Department of Justice and the Department of the Treasury. During the 1930s, Presidents Herbert Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt tried to weaken GAO but failed because Congress stood by the agency.

GAO's office environment in the 1920s and 1930s differed greatly from that in the modern workplace. Judged by current standards, McCarl seemed a stern taskmaster. He argued that in voucher checking, "numbers make for industry. You get your waste time in a small room where there are three or four girls, or three or four boys, for that matter. When the supervisor is away they are not over industrious usually. Those are the places where they read books and do their knitting."

Early in his tenure, McCarl strictly controlled the work environment of his employees. Bells rang to signal starting and quitting times and the lunch period. According to a 1925 bulletin, the workday began at 9:00 a.m. and ended at 4:30 p.m., with time for a mid-day meal set for 12:30 p.m. to 1:00 p.m. The bulletin stated that "clerks and employees will not be permitted to visit each other or to receive visits during office hours, except on official business, and then only with the knowledge and concurrence of their immediate official superiors. Frequenting or loitering in the corridors of the buildings will not be permitted." The bulletin warned that the Comptroller General would take "suitable action" if he learned of employees leaving before 12:30 p.m. or 4:30 p.m.

McCarl relaxed some rules later in his tenure. In 1927, he wrote in GAO's annual report that "enthusiasm has been the keynote of service in the General Accounting Office. The personnel of the office has during the year been alert, capable, and industrious." In fact, McCarl added that the improvement in morale was due "to a lessening of control by restrictive regulations, and a broadening of individual trust and responsibility."

John R. McCarl, Comptroller General, 1921-1936

A tenacious financial watchdog, McCarl left a strong imprint of independence and integrity on the young agency. As the Comptroller General's 15-year term expired in 1936, editorial columnists pointed to his accomplishments: "Among the welter of Washington's yes-men, he was a forthright, solitary and heartening no-man," commented the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. The Hartford Courant noted, "McCarl was neither negligent, careless nor open to 'suggestion.' He made his rulings without fear or favor."

When he left office, McCarl sent a letter to GAO's employees in which he thanked them for their efforts and urged them to keep fighting on for "honesty in government."

| Return to Table of Contents | < Previous Chapter | Next Chapter > |