Caribbean Water Science Center Science Plan 1999

Table of Contents

Introduction

Issues

Introduction

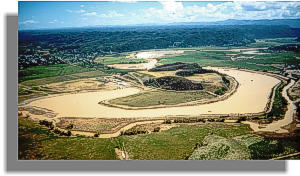

Several rainfall deficient periods in the 1990’s and an aging public water-supply infrastructure have seriously affected the ability of our cooperators to deliver a continuous supply of potable water to the 4 million people living in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. In addition, during this decade more hurricanes and droughts have impacted the islands than during the previous 50 years.Severe water rationing has been implemented three times during the 1990's in Puerto Rico. At the same time, significant agricultural losses, valued in the $100's of millions have occurred. A drought in 1994-95 affected more than one million people in the San Juan metropolitan area who endured a regimen of water rationing that lasted for six months in which sections of San Juan had their water-distribution networks shut off on alternate days. Several rainfall deficient periods in the 1990’s and an aging public water-supply infrastructure have seriously affected the ability of our cooperators to deliver a continuous supply of potable water to the 4 million people living in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. In addition, during this decade more hurricanes and droughts have impacted the islands than during the previous 50 years.Severe water rationing has been implemented three times during the 1990's in Puerto Rico. At the same time, significant agricultural losses, valued in the $100's of millions have occurred. A drought in 1994-95 affected more than one million people in the San Juan metropolitan area who endured a regimen of water rationing that lasted for six months in which sections of San Juan had their water-distribution networks shut off on alternate days. During the winter and spring of 1997-98, more than two hundred thousand people in northwestern Puerto Rico experienced severe rationing of public-supplied water as water level in their principal reservoir, Lago Guajataca, fell 10 meters due to rainfall deficits and sustained withdrawals. During the 1990's, annual rainfall accumulation has been the lowest of the 20th century at 7 of the 12 stations with the longest period of record in Puerto Rico, and the second lowest at the remaining five stations. During the winter and spring of 1997-98, more than two hundred thousand people in northwestern Puerto Rico experienced severe rationing of public-supplied water as water level in their principal reservoir, Lago Guajataca, fell 10 meters due to rainfall deficits and sustained withdrawals. During the 1990's, annual rainfall accumulation has been the lowest of the 20th century at 7 of the 12 stations with the longest period of record in Puerto Rico, and the second lowest at the remaining five stations. This rainfall deficit may be an indication of a regional drying trend that makes large populations in the West Indies vulnerable to water shortages. The total population of the 24 island nations in the West Indies is 37 million. The critical water shortages that have occurred in Puerto Rico, the third most populous island in the West Indies, provide an example of the impact of water resource shortages on regional population.Hurricanes, or other tropical disturbances, are the dominant type of high-magnitude storms affecting Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Hurricanes Hugo, Marilyn, Hortense, and Georges have all struck the islands in the last 10 years. Hurricane rainfall totals during the 20th century have averaged 300 to 800 millimeters (mm) during a 24 to 48 hour period, and most of the peak discharge of record for the surface water gaging station network have been associated with hurricanes. This rainfall deficit may be an indication of a regional drying trend that makes large populations in the West Indies vulnerable to water shortages. The total population of the 24 island nations in the West Indies is 37 million. The critical water shortages that have occurred in Puerto Rico, the third most populous island in the West Indies, provide an example of the impact of water resource shortages on regional population.Hurricanes, or other tropical disturbances, are the dominant type of high-magnitude storms affecting Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Hurricanes Hugo, Marilyn, Hortense, and Georges have all struck the islands in the last 10 years. Hurricane rainfall totals during the 20th century have averaged 300 to 800 millimeters (mm) during a 24 to 48 hour period, and most of the peak discharge of record for the surface water gaging station network have been associated with hurricanes. In addition, these storms have typically been responsible for the largest amounts of suspended sediment transport documented in Puerto Rico. For example, sediment transport associated with Hurricane Hortense, September 1996, measured at the Río Grande de Loíza station downstream of the Lago Loíza reservoir, had a single-day total of 1.36 million metric tonnes. This represents 95 percent of the sediment load for the entire year. Peak discharge was 6,315 cubic meters per second, the greatest ever recorded for this station, whose drainage area is 539 square kilometers.Puerto Rico’s population density is among the highest in the world, about 440 people per square kilometer. The U.S. Virgin Islands are also densely populated with more than 300 people per square kilometer. The population growth rate in Puerto Rico shows a general decline since 1970, being 2.8 percent per year (%/y) between 1970 and 1980, and 1.4 %/y between 1980 and 1990. However, the population has increased from 2.7 million in 1970 to 3.8 million in 1995. In addition, these storms have typically been responsible for the largest amounts of suspended sediment transport documented in Puerto Rico. For example, sediment transport associated with Hurricane Hortense, September 1996, measured at the Río Grande de Loíza station downstream of the Lago Loíza reservoir, had a single-day total of 1.36 million metric tonnes. This represents 95 percent of the sediment load for the entire year. Peak discharge was 6,315 cubic meters per second, the greatest ever recorded for this station, whose drainage area is 539 square kilometers.Puerto Rico’s population density is among the highest in the world, about 440 people per square kilometer. The U.S. Virgin Islands are also densely populated with more than 300 people per square kilometer. The population growth rate in Puerto Rico shows a general decline since 1970, being 2.8 percent per year (%/y) between 1970 and 1980, and 1.4 %/y between 1980 and 1990. However, the population has increased from 2.7 million in 1970 to 3.8 million in 1995.

Population of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands |

During this period (1970 to 1995), water use has risen at an average annual rate of 1.6 %/y from 1.5 million cubic meters per year (m3/y) in 1970 to 2.1 million m3/y in 1995. In addition, surface-water storage has been reduced by the high sediment loads of river systems in which the Puerto Rican reservoirs have been constructed. For example, the annual rate of storage loss at the Lago Loíza reservoir, which supplies about half of the public water supply to the San Juan Metropolitan area, was 1.3 percent, between 1953, when the reservoir was impounded, and 1994. The sedimentation has reduced the reservoir’s firm yield from about 50 million gallon per day (Mgal/d) to about 35 Mgal/d. These high population densities combined with complex geology, high relief (1,338 meters on Puerto Rico), and the short distance (maximum of 35 kilometers) between the insular hydrologic divide and the sea, create and drive many of the water-resources issues that the Caribbean District is facing in the next millennium. This brief description of some water-resource related problems provides the setting for USGS Caribbean District research and program direction in the future.One of the most critical issues is water availability: both Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands face difficulties for supplying their future generations. Although the situation for Puerto Rico is vastly different from that of the smaller Caribbean islands, it has a water shortage stemming from rapid urban development, increased consumption by all economic sectors, deteriorating water quality, and aging infrastructure. To solve some of these problems, the Commonwealth government has recently built a major 70-kilometer-long pipeline to supply communities along the north coast and the San Juan Metropolitan area and begun several additional water infrastructure projects in other parts of the island. The U.S. Virgin Islands lack surface water sources and must rely on desalinization of seawater for their main water supply. Their limited ground-water resources and coastal environment are under constant danger from pollution from industry, septic and leaking underground storage tanks, and saline-water intrusion. These two different realities provide for unusual opportunities for applied hydrologic research in which the USGS Caribbean District should play a major role. These high population densities combined with complex geology, high relief (1,338 meters on Puerto Rico), and the short distance (maximum of 35 kilometers) between the insular hydrologic divide and the sea, create and drive many of the water-resources issues that the Caribbean District is facing in the next millennium. This brief description of some water-resource related problems provides the setting for USGS Caribbean District research and program direction in the future.One of the most critical issues is water availability: both Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands face difficulties for supplying their future generations. Although the situation for Puerto Rico is vastly different from that of the smaller Caribbean islands, it has a water shortage stemming from rapid urban development, increased consumption by all economic sectors, deteriorating water quality, and aging infrastructure. To solve some of these problems, the Commonwealth government has recently built a major 70-kilometer-long pipeline to supply communities along the north coast and the San Juan Metropolitan area and begun several additional water infrastructure projects in other parts of the island. The U.S. Virgin Islands lack surface water sources and must rely on desalinization of seawater for their main water supply. Their limited ground-water resources and coastal environment are under constant danger from pollution from industry, septic and leaking underground storage tanks, and saline-water intrusion. These two different realities provide for unusual opportunities for applied hydrologic research in which the USGS Caribbean District should play a major role.

|

Throughout the 42 years that the USGS has maintained a continuous presence in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, many studies have been completed for lakes, watersheds, and individual river basins. We should now begin to emphasize on long-term hydrologic monitoring and interpretive studies with potential applicability on a broader scale to other tropical areas and more specifically to the Caribbean and Central America. The USGS has collected many years of useful data that need to be interpreted at the various scales to give the full regional perspective on water-resource issues in the Caribbean. The Caribbean District has a talented staff of scientists, engineers, and technicians that can conduct the necessary studies.The Science Plan for the Caribbean District has been prepared following the issues presented in the Southeastern Region, “Planning for 2003-2008 in the Southeastern Region of the Water Resources Division.” The present level of understanding of each hydrologic and program support category is briefly presented followed by a list of information needs and deficiencies and the Caribbean District's desired scientific direction for its hydrology program. The strategies and goals presented in this document are expected to be valid for approximately five years, but will be reassessed every two years so as to maintain their relevance and reflect as accurately as possible the Caribbean District program objectives.The USGS, Caribbean District is in a privileged position to help water resources managers, inform the general public, and encourage wide participation in water-management decisions in the Caribbean region. To assist in this process, the USGS has established an integrated surface water, ground water, and water-quality monitoring network. The Caribbean District is using GIS technology and dual-language fact sheets to disseminate the data to the general public. Some of this data is now available to the public on the internet. The network consists of 129 hydrologic data-collection sites equipped with satellite telemetry instrumentation. It includes streamflow, lake-stage, ground-water, rainfall, and meteorological stations. The Ground Water Site Inventory includes data from over 5,000 wells in Puerto Rico and 1,000 wells in the U.S. Virgin Islands.Data gathered in past years has been used by the Caribbean District to establish the long-term yield of major watersheds and reservoirs in Puerto Rico and build ground-water models for major aquifers in both Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Flow duration and flood frequency studies have been conducted and updated studies will be published soon. These studies are essential in managing the water resources of the islands.Real-time simulation of river flows during storm events has been conducted for the Río Grande de Loíza and its major tributaries. Additional basins like the Río Grande de Arecibo, Río de la Plata, and the Río Grande de Manatí should be modeled in the future. It includes streamflow, lake-stage, ground-water, rainfall, and meteorological stations. The Ground Water Site Inventory includes data from over 5,000 wells in Puerto Rico and 1,000 wells in the U.S. Virgin Islands.Data gathered in past years has been used by the Caribbean District to establish the long-term yield of major watersheds and reservoirs in Puerto Rico and build ground-water models for major aquifers in both Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Flow duration and flood frequency studies have been conducted and updated studies will be published soon. These studies are essential in managing the water resources of the islands.Real-time simulation of river flows during storm events has been conducted for the Río Grande de Loíza and its major tributaries. Additional basins like the Río Grande de Arecibo, Río de la Plata, and the Río Grande de Manatí should be modeled in the future.

Water-Resources Management

The network consists of 129 hydrologic data-collection sites equipped with satellite telemetry instrumentation. It includes streamflow, lake-stage, ground-water, rainfall, and meteorological stations. The Ground Water Site Inventory includes data from over 5,000 wells in Puerto Rico and 1,000 wells in the U.S. Virgin Islands.Data gathered in past years has been used by the Caribbean District to establish the long-term yield of major watersheds and reservoirs in Puerto Rico and build ground-water models for major aquifers in both Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Flow duration and flood frequency studies have been conducted and updated studies will be published soon. These studies are essential in managing the water resources of the islands.Real-time simulation of river flows during storm events has been conducted for the Río Grande de Loíza and its major tributaries. Additional basins like the Río Grande de Arecibo, Río de la Plata, and the Río Grande de Manatí should be modeled in the future. The network consists of 129 hydrologic data-collection sites equipped with satellite telemetry instrumentation. It includes streamflow, lake-stage, ground-water, rainfall, and meteorological stations. The Ground Water Site Inventory includes data from over 5,000 wells in Puerto Rico and 1,000 wells in the U.S. Virgin Islands.Data gathered in past years has been used by the Caribbean District to establish the long-term yield of major watersheds and reservoirs in Puerto Rico and build ground-water models for major aquifers in both Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Flow duration and flood frequency studies have been conducted and updated studies will be published soon. These studies are essential in managing the water resources of the islands.Real-time simulation of river flows during storm events has been conducted for the Río Grande de Loíza and its major tributaries. Additional basins like the Río Grande de Arecibo, Río de la Plata, and the Río Grande de Manatí should be modeled in the future.

Information Needs and Deficiencies

- Data collection. While some basins have numerous gaging stations, several large areas of the islands are ungaged.

- Because of the high sediment loads, the capacity of many of the important water-supply reservoirs in Puerto Rico is decreasing rapidly.

- There is a lack of understanding on the effects of land-cover changes (particularly urbanization) on water-quality, baseflow, and peak flows of rivers.

- There is a general lack of understanding on the definition, on-set, and frequency of droughts.

- Alternate sources of water need be established to mitigate severe water rationing during droughts.

- There is a need for defining the quantity and quality of water supply sources at a municipal scale for sustained development within the municipal boundaries.

- Lack of accurate, up-to-date topographic maps hinders water-resources management.

- Real-time simulation of river flows during floods are needed for the Río Grande de Arecibo, Río de la Plata, and the Río Grande de Manatí.

Program Opportunities

- Assess present surface-water monitoring network to define optimum coverage of the Caribbean District for the intended purposes of the network and taking into account our cooperators strategies to meet current and future demands.

- Continue periodic mapping of reservoir bathymetry in Puerto Rico to update storage capacities and rates of sedimentation. Conduct interpretive studies of the results of the long term monitoring of selected rivers for sediment loads and characteristics.

- Conduct detailed studies to determine the effects of land-cover changes (particularly urbanization) on water-quality, baseflow, and flood peaks of rivers. Collaborate with the Puerto Rico Department of Health in its development of a Source Water Assessment Program for drinking water systems throughout Puerto Rico.

- Develop an improved understanding of droughts by proposing a better definition of droughts, developing a drought index, and studying their recurrence intervals.

- Identify alternative sources of drinking water for use during droughts.

- Promote the development of water assessments for the municipalities of Puerto Rico.

- Work together with the National Mapping Division to produce updated topographic maps of Puerto Rico.

- Complete real-time simulation of rivers during floods for the Río Grande de Arecibo, Río de la Plata, and the Río Grande de Manatí.

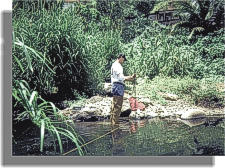

Ecological Health of Streams

Because of the highly urbanized and industrialized nature of the islands, ecological problems abound. The rivers, lakes, wetlands, mangroves, estuaries, and coastal environments have all suffered from a variety of problems, among which sedimentation and eutrophication are major concerns. Major riverine and estuarine systems in Puerto Rico have been under urban development and have been affected by channelization, dredging and filling operations, oil spills, and untreated sewer discharges. Instances of poisoned fish and fowl have been observed in the region. The deteriorating ecologic health of streams and rivers contributes to the poor ecological health of the coastal environment. In the Caribbean the destruction of coral reefs has adversely impacted the tourism industry. Along the coasts, coral reefs serve as a rampart against strong surf erosion, especially during the winter months. Loss of the reefs will result in widespread erosion over tens of kilometers of coastline.The Caribbean District has conducted major studies to determine the water and sediment quality in streams, reservoirs, estuaries, and coastal lagoons and other coastal environments. In cooperation with the Geologic Division and the Biological Resources Division, state-of-the-art techniques, including radiometric dating with Cs-137, have been used to determine the history of contamination composition and assess the health of corals.Sand and gravel mining within river channels and along flood plains has resulted in the destruction and alteration of natural habitats. As a result indigenous populations of species have been declining at an alarming rate. Because of the highly urbanized and industrialized nature of the islands, ecological problems abound. The rivers, lakes, wetlands, mangroves, estuaries, and coastal environments have all suffered from a variety of problems, among which sedimentation and eutrophication are major concerns. Major riverine and estuarine systems in Puerto Rico have been under urban development and have been affected by channelization, dredging and filling operations, oil spills, and untreated sewer discharges. Instances of poisoned fish and fowl have been observed in the region. The deteriorating ecologic health of streams and rivers contributes to the poor ecological health of the coastal environment. In the Caribbean the destruction of coral reefs has adversely impacted the tourism industry. Along the coasts, coral reefs serve as a rampart against strong surf erosion, especially during the winter months. Loss of the reefs will result in widespread erosion over tens of kilometers of coastline.The Caribbean District has conducted major studies to determine the water and sediment quality in streams, reservoirs, estuaries, and coastal lagoons and other coastal environments. In cooperation with the Geologic Division and the Biological Resources Division, state-of-the-art techniques, including radiometric dating with Cs-137, have been used to determine the history of contamination composition and assess the health of corals.Sand and gravel mining within river channels and along flood plains has resulted in the destruction and alteration of natural habitats. As a result indigenous populations of species have been declining at an alarming rate.

Information Needs and Deficiencies

- There is a lack of understanding of the quantity and quality of water needed to maintain a healthy environment in rivers from the headwaters to the coast.

- No scientifically-based geographic assessment exists of the waterborne microbiologic threats to human health.

- The effects of sand and gravel mining on the ecologic health of streams is not well understood.

- There is a lack of data on the long-term effects of sedimentation, wastewater discharges, and other sources of pollution on marine ecosystems.

- There is a pattern of coral bleaching and coral deterioration throughout the Caribbean that merits further study since the generalized nature of the problem creates cause for concern.

Program Opportunities

- Propose to study, in cooperation with the Biological Resources Division, the minimum flows for sustainability of ecosystems and the effects of withdrawals on ecosystems health throughout the island.

- Propose to conduct a scientifically-based geographic assessment of the waterborne microbiologic threats to human health. Possible threats include schistosomiasis, giardia, cryptosporidium, bacteria, viruses, protozoa, and potentially toxic algae.

- Propose to conduct studies of the effects of sand and gravel mining on the ecologic health of streams.

- Study, in cooperation with the Geologic Division, the effects of sedimentation, discharge of primary- and secondary-treated wastewater through ocean outfalls, and other sources of pollution on the marine ecosystems.

- Monitor, in cooperation with the Geologic Division, coral health throughout the Caribbean.

Watershed Issues

The principle watershed issue in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands is the effect of landcover changes on peak flow, baseflow, and water quality. In addition, these land-cover changes affect the amount of potable water available at intakes that depend on run-of-the-river low flow and the amount of storage in reservoirs.The USGS-funded Luquillo Water, Energy, and Biogeochemical Budgets (WEBB) program is an example of watershed-scale research. The study is aimed at improving understanding of processes controlling terrestrial water, energy, and biogeochemical fluxes, their interactions, and their relations to climatic variables; and the ability to predict water, energy, and biogeochemical budgets over a range of spatial and temporal scales. The work of Luquillo WEBB researchers focuses on water, energy, carbon, nutrient, dissolved-constituent, and sediment (suspended and bed load) budgets in four watersheds located in eastern Puerto Rico. Two of the watersheds are in tropical rain forest in the Luquillo Experimental Forest (LEF), an 11,300 hectare forest preserve administered by the U.S. Forest Service. Two additional watersheds are located in the agriculturally-developed and partially urbanized Río Grande de Loíza basin. The WEBB approach serves as a model for watershed- to island-scale research that the USGS can conduct in Puerto Rico. The principle watershed issue in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands is the effect of landcover changes on peak flow, baseflow, and water quality. In addition, these land-cover changes affect the amount of potable water available at intakes that depend on run-of-the-river low flow and the amount of storage in reservoirs.The USGS-funded Luquillo Water, Energy, and Biogeochemical Budgets (WEBB) program is an example of watershed-scale research. The study is aimed at improving understanding of processes controlling terrestrial water, energy, and biogeochemical fluxes, their interactions, and their relations to climatic variables; and the ability to predict water, energy, and biogeochemical budgets over a range of spatial and temporal scales. The work of Luquillo WEBB researchers focuses on water, energy, carbon, nutrient, dissolved-constituent, and sediment (suspended and bed load) budgets in four watersheds located in eastern Puerto Rico. Two of the watersheds are in tropical rain forest in the Luquillo Experimental Forest (LEF), an 11,300 hectare forest preserve administered by the U.S. Forest Service. Two additional watersheds are located in the agriculturally-developed and partially urbanized Río Grande de Loíza basin. The WEBB approach serves as a model for watershed- to island-scale research that the USGS can conduct in Puerto Rico.

Information Needs and Deficiencies

- The general sources of sediment and their transport mechanisms need to be defined.

- GIS-based models and applications that can forecast the effect of land-cover changes on peak flow, baseflow, and water quality are needed.

- There is a lack of understanding of long-term climatic changes on the hydrologic systems of the Caribbean.

- A shortage of aggregate for construction has increased pressure on fluvial systems because of increased extraction permits. The short and long term effects of sand extraction from rivers are poorly understood.

Program Opportunities

- Analyze sediment records to define watershed-scale sediment loads, develop sediment transport models for selected basins, and integrate the results for the entire island of Puerto Rico. Using these models, conduct geomorphologic studies for selected river drainage basins to determine sources of fluvial sediment and residence time of sediment in active and semi-active storage compartments.

- Develop GIS-based models and applications that can forecast the effect of land-cover change on peak flow, baseflow, and water quality.

- Conduct paleoclimate research to reconstruct past hydrologic regimes in Puerto Rico and their impact on the development of present hydrologic conditions.

- Initiate site specific studies of the downstream and upstream effects of rivers and extraction with attention to channel bed and bank erosion.

Fate and Transport of Contaminants

The Caribbean District has conducted synoptic surveys of surface water, ground water, and water quality and stream, reservoir and estuary sediments that have shown the persistence of contamination in fluvial, lacustrine, estuarine, and ground-water systems. Among the pollutants found are mercury, lead, arsenic, PCB’s, DDT, and trichloroethylene. However, only one of these studies, the Vega Alta ground-water transport model, tracks the movement of volatile organic compounds from the source through the upper aquifer. The other studies have been synoptic surveys of sediment characterization. More definitive studies of the fate and transport of contaminants are needed. The Caribbean District has conducted synoptic surveys of surface water, ground water, and water quality and stream, reservoir and estuary sediments that have shown the persistence of contamination in fluvial, lacustrine, estuarine, and ground-water systems. Among the pollutants found are mercury, lead, arsenic, PCB’s, DDT, and trichloroethylene. However, only one of these studies, the Vega Alta ground-water transport model, tracks the movement of volatile organic compounds from the source through the upper aquifer. The other studies have been synoptic surveys of sediment characterization. More definitive studies of the fate and transport of contaminants are needed.

Information Needs and Deficiencies

- There is a lack of knowledge of the complete geographic distribution of many contaminates.

- The drinking water systems in Puerto Rico have been found to contain varying levels of trihalomethanes and other disinfection by-products. There is a lack of understanding of the source and concentrations of the precursors to disinfection by-products.

- In Puerto Rico there are many abandoned landfills and clandestine dump sites. There is a need to study the fate and transport of toxic material that may have been deposited in these sites.

- Half of the households in Puerto Rico are unsewered. The impact of the unsewered households on the streams in Puerto Rico is unknown.

- The impact of herds of beef and dairy cattle in Puerto Rico on surface water quality is unknown.

- A recent study in north-central Puerto Rico indicates that about 90 percent of the nitrogen applied as fertilizer is in transit in the vadose zone. Further studies are needed to determine the amount of nitrate in storage in the vadose zone and its rate of movement toward the water table in both unsewered communities and agricultural areas.

Program Opportunities

- Propose to conduct island-wide surveys of the concentration of metals and persistent organic contaminants in ground water and lacustrine and estuarine sediments. Particular attention should be given to areas downstream from industrialized and agri-business zones.

- Propose to conduct a study to determine the source and concentrations of the precursors to disinfection by-products.

- Propose to study the fate and transport of toxic material that may have been deposited in the many abandoned landfills and clandestine dump sites in Puerto Rico.

- Conduct a study of the effects of unsewered households on the microbiological and chemical quality of streams in Puerto Rico.

- Conduct a study of the impact of cattle on stream eutrophication and micro-biological quality in Puerto Rico.

- Conduct studies to determine the amount of nitrate in storage in the vadose zone and its rate of movement toward the water table in both unsewered communities and agricultural areas within different hydrogeological conditions (volcanics, coastal alluvial plain, and karst).

Water Resources in Coastal Areas

The most important aquifers in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands are in coastal areas. These aquifers have been negatively impacted since the early part of this century by large scale agricultural land reclamation and malaria control projects through construction of drainage and dewatering works. This has led to widespread saline-water encroachment from the coast and thinning of the freshwater lens. Within the past 30 years, this problem have been exacerbated by aquifer overdraft and increased withdrawals of water from streams which has altered the hydrodynamic equilibrium of the saline-water wedge. The most important aquifers in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands are in coastal areas. These aquifers have been negatively impacted since the early part of this century by large scale agricultural land reclamation and malaria control projects through construction of drainage and dewatering works. This has led to widespread saline-water encroachment from the coast and thinning of the freshwater lens. Within the past 30 years, this problem have been exacerbated by aquifer overdraft and increased withdrawals of water from streams which has altered the hydrodynamic equilibrium of the saline-water wedge. Monitoring the location of the saline-freshwater interface with wells and both surface and borehole geophysics has begun. Consequently, the location of the interface has been established in many areas, but its rate of movement cannot be known without long-term monitoring. However, only few synoptic surveys have been conducted to relate stream discharge with the location of the saline-water wedge at estuaries. Monitoring the location of the saline-freshwater interface with wells and both surface and borehole geophysics has begun. Consequently, the location of the interface has been established in many areas, but its rate of movement cannot be known without long-term monitoring. However, only few synoptic surveys have been conducted to relate stream discharge with the location of the saline-water wedge at estuaries. Throughout the south coast changes in irrigation practices from furrow irrigation with surface water to micro-irrigation with ground water is seriously depleting the South Coastal Plain aquifer system in Puerto Rico, an important agriculture resource. Sustainable development of this aquifer will require artificial recharge measures to prevent further saline intrusion into the aquifer. Throughout the south coast changes in irrigation practices from furrow irrigation with surface water to micro-irrigation with ground water is seriously depleting the South Coastal Plain aquifer system in Puerto Rico, an important agriculture resource. Sustainable development of this aquifer will require artificial recharge measures to prevent further saline intrusion into the aquifer.

Information Needs and Deficiencies

- The exact vertical position of the saline-freshwater interface needs to be better defined in many areas. The rate of movement of the interface needs to be determined with long-term monitoring.

- The relation of the position of the saline-water in wedge in streams needs to be defined.

- A study is needed to document the changes that have occurred in the south coastal plain aquifer system in Puerto Rico due to the changes in irrigation practices

Program Opportunities

- Determine the exact vertical position of the saline-freshwater interface in the important aquifers in Puerto Rico. Continue long-term monitoring to determine the rate of movement of the interface in the aquifer. All coastal monitoring wells will be tied to mean sea-level datum.

- Determine the displacement of the saline-water wedge in relation to stream discharge and tides in the island’s major estuaries.

- Determine the areas suitable for artificial recharge to the south coastal plain aquifer system and conduct a pilot study to determine the effect of artificial recharge on the aquifer.

Surface-Water Ground-Water Interactions

Flood control projects, specifically channelization, have altered the surface-water ground-water relationships in many areas of Puerto Rico. The documented changes have varied from degradation of water-quality to complete disruption of the surface-water ground-water interaction as a result of the diversion of rivers from natural to artificial channels. The Caribbean District has conducted synoptic ground-water studies in many areas where the rivers have subsequently been channelized. There is a need to assess the effects of channelization on ground-water resources in these areas.Ground-water withdrawals have detrimentally affected many wetland areas in Puerto Rico, such as the Laguna Tortuguero, the largest freshwater lagoon in Puerto Rico. The Caribbean District is conducting a limnological study of this lagoon, whose primary freshwater source is ground water.The demand for water resources for public supply in the interior of Puerto Rico has led to a rapid rise in the number of water wells constructed in the area. The long-term impact of this trend on low-flow discharges of streams is unknown. Flood control projects, specifically channelization, have altered the surface-water ground-water relationships in many areas of Puerto Rico. The documented changes have varied from degradation of water-quality to complete disruption of the surface-water ground-water interaction as a result of the diversion of rivers from natural to artificial channels. The Caribbean District has conducted synoptic ground-water studies in many areas where the rivers have subsequently been channelized. There is a need to assess the effects of channelization on ground-water resources in these areas.Ground-water withdrawals have detrimentally affected many wetland areas in Puerto Rico, such as the Laguna Tortuguero, the largest freshwater lagoon in Puerto Rico. The Caribbean District is conducting a limnological study of this lagoon, whose primary freshwater source is ground water.The demand for water resources for public supply in the interior of Puerto Rico has led to a rapid rise in the number of water wells constructed in the area. The long-term impact of this trend on low-flow discharges of streams is unknown.

Information Needs and Deficiencies

- There is a need to assess the effects of channelization on ground-water resources in many areas in Puerto Rico.

- The effects of ground-water withdrawals on wetlands in Puerto Rico are undocumented.

- The effects of the recent rapid rise in the number of water wells constructed in the interior of Puerto Rico on the low-flow discharges of streams is unknown.

Program Opportunities

- Conduct studies to determine the effects of channelization on ground-water resources in Puerto Rico. Particular attention will be paid to areas where ground-water studies were conducted prior to channelization.

- Continue to study the effects of ground-water withdrawals on the wetlands of Puerto Rico.

- Conduct a study to determine the effects of increased ground-water withdrawals in the interior upland of Puerto Rico on the low-flow discharges of streams.

Hydrologic Hazards

According to Water Resources Division Memorandum No. 99.30 entitled “Priority Issues for the Federal-State Cooperative Program, Fiscal Year 2000”:

HYDROLOGIC HAZARDS--Economic losses from hydrologic hazards amount to several billions of dollars annually. Monitoring the occurrence and magnitude of these extreme events and studying the basic processes underlying these hazards will lead to improving the ability to forecast probability of occurrence and likely magnitudes, and help prepare for and prevent disasters. Increasing real-time access to streamflow data through telemetry at gaging stations and through improved presentation on the Internet remains particularly important for disaster preparedness.

The major hydrologic hazards in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands are floods, droughts, and landslides. In the last ten years four hurricanes have struck the islands: Hurricanes Hugo, Marilyn, Hortense, and Georges. The total damage in Puerto Rico from Hurricane Georges was estimated to be 1.9 billion dollars. There have been three major droughts in Puerto Rico in this decade. In terms of loss of life, the worst landslide disaster in the history of the United States took place in Ponce, Puerto Rico. In 1985, a tropical depression which later became Tropical Storm Isabel, dropped a total of 625 millimeters of rain in 24 hours. A hillslope in Barrio Mameyes, saturated by this rainfall, failed and more than 120 people died as an entire hillside covered with homes slid downslope.In response to these hydrologic hazards, the Caribbean District in cooperation with local government agencies has established a real-time hazard alert network. The network consists of 129 hydrologic data-collection sites equipped with satellite telemetry instrumentation. It includes streamflow, lake-stage, rainfall, and meteorological stations in Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and, after Hurricane Mitch, three stations in Central America.Most of the flood maps prepared in Puerto Rico by the USGS documented floods that occurred prior to the 1980’s. Since almost all the flood plains inundated by these past floods have experienced topographic changes caused mainly by stream channelization and the construction of highways and levees the effect of these structures in the flood levels is unknown. Consequently, new flood maps need to be prepared. The major hydrologic hazards in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands are floods, droughts, and landslides. In the last ten years four hurricanes have struck the islands: Hurricanes Hugo, Marilyn, Hortense, and Georges. The total damage in Puerto Rico from Hurricane Georges was estimated to be 1.9 billion dollars. There have been three major droughts in Puerto Rico in this decade. In terms of loss of life, the worst landslide disaster in the history of the United States took place in Ponce, Puerto Rico. In 1985, a tropical depression which later became Tropical Storm Isabel, dropped a total of 625 millimeters of rain in 24 hours. A hillslope in Barrio Mameyes, saturated by this rainfall, failed and more than 120 people died as an entire hillside covered with homes slid downslope.In response to these hydrologic hazards, the Caribbean District in cooperation with local government agencies has established a real-time hazard alert network. The network consists of 129 hydrologic data-collection sites equipped with satellite telemetry instrumentation. It includes streamflow, lake-stage, rainfall, and meteorological stations in Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and, after Hurricane Mitch, three stations in Central America.Most of the flood maps prepared in Puerto Rico by the USGS documented floods that occurred prior to the 1980’s. Since almost all the flood plains inundated by these past floods have experienced topographic changes caused mainly by stream channelization and the construction of highways and levees the effect of these structures in the flood levels is unknown. Consequently, new flood maps need to be prepared.

Information Needs and Deficiencies

- The real-time hazard alert network needs to be expanded to cover other areas. Most of the USGS rain gage network is located in valley bottoms at surface-water gaging stations. New rain gages at ridge and hill top locations are needed.

- Although good, the user interface of the real-time hazard alert network, could be improved to make it easily understood by the cooperators and the general public.

- In Puerto Rico the correlation between flood levels and flood hazard zones is not well established.

- Instrumentation is needed to monitor soil moisture during extreme hydrologic events and a methodology needs to be developed to determine landslide hazards.

- Flood maps need to be prepared for future floods in flood plains where numerous changes to the topography have occurred.

- Only limited assessment of landslide susceptibility has been completed in Puerto Rico and none has been completed in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Program Opportunities

- Expand the real-time hazard alert network to cover other areas in the Caribbean Region and Central America, as well as improve the topographic distribution of rain gages in Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands.

- Continue to improve the user interface of the real-time hazard alert network for our cooperators and the general public through the internet.

- Provide information to decision making agencies on the relationship of flood levels to hazard zones.

- Install soil tensiometers at strategic telemetered locations throughout Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to measure soil moisture during hydrologic events and develop a methodology to determine landslide hazards.

- Prepare flood maps after major floods.

- Develop landslide susceptibility maps for Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands at the municipality or quadrangle scale.

Additional Program Opportunities

The Caribbean District will continue to promote the development of cooperative programs with other Federal and local agencies, municipal governments, universities, and research centers. The District will also promote and develop cooperative programs with the Geologic Division, Biological Resources Division, and National Mapping Division to further the objectives and goals of the U.S. Geological Survey as a whole.

International Programs

The Caribbean District has contributed its expertise in short term assignments to the Lesser Antilles (Dominica, St. Lucia, St. Vincent), the Greater Antilles (Haiti and the Dominican Republic), and Central America (Costa Rica and most recently, Honduras). Currently, the Caribbean District is collaborating in an interdivisional, multidisciplinary effort to help the Central American nations that were devastated by Hurricane Mitch. Because of the location of the Caribbean District and because of our large number of Spanish-speaking employees, we are especially suited for such international opportunities. Caribbean District employees have installed three gaging stations with satellite near real time transmissions by telemetry in Honduras. About 15 additional stations will be installed in Honduras, and a yet undetermined number in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Caribbean District employees are playing a major role in the training and capacity building of Honduran technicians and professionals. Because of the location of the Caribbean District and because of our large number of Spanish-speaking employees, we are especially suited for such international opportunities. Caribbean District employees have installed three gaging stations with satellite near real time transmissions by telemetry in Honduras. About 15 additional stations will be installed in Honduras, and a yet undetermined number in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Caribbean District employees are playing a major role in the training and capacity building of Honduran technicians and professionals.

Watershed and Ecosystems in the Tropics (WET)

The Caribbean District is already involved in watersheds studies in unique tropical settings, such as the rainforest in Luquillo.  Because of our expertise in this area, the Caribbean District should be involved in a new interdivisional multidisciplinary process-oriented study named Watersheds and Ecosystems in the Tropics (WET). This program combines the expertise in the Biological Resources Division, Geological Division, and Water Resources Division to provide fundamental information to resource managers on tropical islands.The rationale behind the WET study is that the rainforests and reefs are biologically unique and economically important, but are threatened by many environmental pressures. There is a need for both intensive multidisciplinary watershed-scale studies and long-term monitoring to assess the stability of these resources and their outlook for the future. Because of our expertise in this area, the Caribbean District should be involved in a new interdivisional multidisciplinary process-oriented study named Watersheds and Ecosystems in the Tropics (WET). This program combines the expertise in the Biological Resources Division, Geological Division, and Water Resources Division to provide fundamental information to resource managers on tropical islands.The rationale behind the WET study is that the rainforests and reefs are biologically unique and economically important, but are threatened by many environmental pressures. There is a need for both intensive multidisciplinary watershed-scale studies and long-term monitoring to assess the stability of these resources and their outlook for the future.

Ground-Water Research in the U.S. Virgin Islands

Since 1985 the Caribbean District has not evaluated the state of the groundwater resources in the U.S. Virgin Islands. There are opportunities for collaboration in determining the water quality of the Tutu embayment aquifer and Kingshill limestone aquifer. Also this will present opportunities for studying bioremediation in fractured-rock aquifers under tropical conditions. Also the District can contribute training in Total Maximum Daily Loads sampling and developing GIS.

Water-Resources Studies for Municipalities

The Caribbean District will continue to develop the program with the municipalities of Puerto Rico. The objective of this program is to help the municipalities have more active participation in the development of their water resources by integrating surface-water, ground-water, and water quality issues within their political boundaries. This work fits very well with the overall Puerto Rico Water Plan.

Plan Implementation

This science plan is dependent upon a highly trained, enthusiastic work force. The following information describes our objectives regarding staffing needs, training, and outreach.

Staffing Needs

The Caribbean District is committed to promote diversity in its work force. During the past year, we have been actively involved in the Bureau Diversity Recruitment Team. The Eastern Region Team I promoted 50 percent of the hirings through this program this year. We have effectively used students for the last three years. This summer, we had nine students participating either as volunteers or as temporary employees. The Caribbean District is facing shortages of employees in the following areas: geographic information systems specialists, hydrologic technicians, and hydrologists. For FY 2000 the District will need at least two full time positions for hydrologic technicians, and one for GIS. The District is generating publications in both English and Spanish and two translator positions are needed. The Caribbean District is facing shortages of employees in the following areas: geographic information systems specialists, hydrologic technicians, and hydrologists. For FY 2000 the District will need at least two full time positions for hydrologic technicians, and one for GIS. The District is generating publications in both English and Spanish and two translator positions are needed.

Training

Training will be provided to all new Caribbean District employees in accordance to policies established by the Southeastern Region and WRD. All Caribbean District employees will be provided with periodic and timely training to maintain and improve their technical expertise in the job-related duties required of them.Provide periodic training in technical report writing and report planning to all Caribbean District authors; both in general terms and with regard to USGS requirements.

Outreach

The Caribbean District currently participates in outreach and education programs. Our main products are the publications generated by water-resources investigation projects. Therefore, we are committed to meeting all report product deadlines for presently active and future projects. The District has cooperated with the National outreach programs in translating into Spanish various outreach publications in-house or through partnership with local universities (for example, Water Research Professional’s Outreach Notebook, GW).Produce publications including, fact sheets, informational pamphlets, and press releases for the purpose of informing and educating the Nation's public about hydrologic concepts and current hydrologic issues affecting or occurring in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. All such publications will be released in both English and Spanish so as to maximize the dissemination of this information throughout Puerto Rico and to enhance USGS visibility in Latin America.Maintain optimal staffing levels and employee preparedness in the Reports Unit so that publications, quality remains high and deadlines are always met. Maintain translation capability to generate additional bilingual publications. The Caribbean District currently participates in outreach and education programs. Our main products are the publications generated by water-resources investigation projects. Therefore, we are committed to meeting all report product deadlines for presently active and future projects. The District has cooperated with the National outreach programs in translating into Spanish various outreach publications in-house or through partnership with local universities (for example, Water Research Professional’s Outreach Notebook, GW).Produce publications including, fact sheets, informational pamphlets, and press releases for the purpose of informing and educating the Nation's public about hydrologic concepts and current hydrologic issues affecting or occurring in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. All such publications will be released in both English and Spanish so as to maximize the dissemination of this information throughout Puerto Rico and to enhance USGS visibility in Latin America.Maintain optimal staffing levels and employee preparedness in the Reports Unit so that publications, quality remains high and deadlines are always met. Maintain translation capability to generate additional bilingual publications.

|