|

Press Release 07-107

Light Brings Out the Worst in Some Disease-Causing Bacteria

Bacteria can sense light, and light exposure increases the virulence of one type of disease-causing bacteria

August 23, 2007

A new study shows that some types of bacteria can sense light, and that exposing one type of disease-causing bacterium--the Brucella bacterium--to light increases its capacity to infect humans and livestock. This study represents the first time that light has been shown to play a role in bacterial virulence (infection).

Brucella bacteria "have been very well studied for years, and no one knew they could sense light," said Trevor Swartz of the University of California, Santa Cruz, the study's lead author. "And now it seems like it's a common thing rather than being an anomaly."

The study, which was partially funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and conducted by an international team of scientists, is described in the August 24 issue of Science.

The scientists found that bacterial sensors are closely related to phototropins-- the light receptors that detect blue light and direct plants to grow towards light sources. "The central message is that many bacteria have signaling proteins that contain the same light-absorbing domain as those found in the higher plants," says Winslow Briggs of the Carnegie Institution, who was a member of the research team. "One of these is a vicious pathogen called Brucella. A species of Brucella is a serious pathogen of cattle that causes abortions of calves, and another species is a nasty pathogen of humans."

The researchers are unsure of how the regulation of virulence by light benefits Brucella. But they suspect that it somehow helps the bacteria overcome the human or animal host's disease-fighting defenses and enables it to reproduce rapidly. They also suspect that light signals the bacteria when it is outside of a host, such as an infected, aborted cow fetus lying in a field. Under such circumstances, increased virulence would help the bacteria survive and infect a new host.

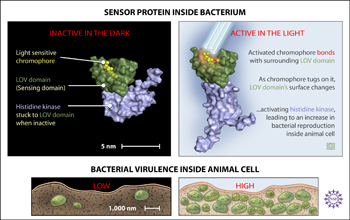

Like plant phototropins, the bacterial sensors have a protein sequence called a LOV (pronounced "love") protein domain, so named because it detects light and resembles some molecular packages that detect oxygen or voltage.

Also with NSF funding, Briggs and a team of researchers discovered the first LOV domain proteins in plant phototropins in 1998. Since then, other researchers have shown that close to 100 different bacteria possess the DNA code for the LOV-domain proteins. But just because the bacteria contain the DNA code for LOV-domain proteins would not necessarily mean that the proteins themselves sense light.

The study in the August 24 issue of Science confirms the light-sensing function of the LOV domain proteins in four bacteria species. But the ubiquity of the light structures in bacteria species suggests that light may play a much more important role in bacterial life and virulence than previously believed.

"The U.S. researchers in this study have been pioneers in the study of light sensing in plants," says Parag Chitnis, an NSF program director. "Their NSF-supported research on plants led to a thread of discoveries that have now revealed the role of light in bacterial virulence in animals. Their work provides an excellent example of how basic research in one area can lead to new insights in a completely unrelated area."

Specifically, the scientists identified the function of LOV-domain proteins in four bacterial species: Brucella melitensis (a human pathogen) Brucella abortus (a cattle pathogen) Pseudomonas syringae (a well-studied plant pathogen),and Erythrobacter litoralis (common in sea water). Their study involved these steps:

- Inserting the genes for the four LOV domain proteins into Escherichia coli, a lab-friendly bacterium that is easy to work with. Next, the bacteria were grown in a darkened lab. Then, the LOV domain proteins were purified under dim red light.

Testing whether the LOV domain proteins demonstrated the photochemical responses expected of a LOV domain protein when the bacterium was flashed by a strobe light. Such a color change would indicate that the LOV domain protein had tightened its grip on a molecular group known as a chromophore that gives color to organic molecules, and changed its shape in ways that activate the rest of the protein. In response to the strobe light, each purified protein showed a color change exactly as expected of a LOV domain protein.

- Testing whether each of the LOV domain proteins functioned in a so-called two-component system, which is the primary mechanism used by bacteria to sense and respond to a wide range of environmental stimuli. In a two-component system, component #1 consists of a sensor domain that includes a sensing domain (such as the LOV-domain protein that responds to light) and an enzyme called a histidine kinase. The histidine kinase responds to activation of the sensing domain by adding phosphate groups to component #2, which is composed of a response regulator. This addition of phosphate groups to the response regulator is called a phosphorylation cascade and activates other molecules.

- Testing whether light played a role in living Brucella abortus, the cause of the cattle disorder known as Brucellosis. This test involved incubating bacteria together with cultured animal cells in dark and light environments, and then measuring the virulence of the bacteria--their ability to reproduce efficiently enough to cause disease within the cultured animal cells.

Results showed that the bacteria's virulence in the dark environment dropped to less than 10 percent of normal virulence. This decrease, which was similar to that achieved by disabling the LOV-domain protein gene in the bacteria, demonstrates that the maximum viruluence of Brucella abortus depends on light.

This study suggests that Brucella abortus responds to light by triggering a phosphorylation that causes the bacterium to reproduce, and thereby increase its virulence. An improved understanding of the relationships between these disease-causing bacteria and light may lead to better disease prevention and treatment methods.

-NSF-

Media Contacts

Lily Whiteman, NSF 703-292-8310 lwhitema@nsf.gov

Hugh Powell, University of California, Santa Cruz 831-459-4353 aphriza@gmail.com

Program Contacts

Parag Chitnis, NSF 703-292-7132 pchitnis@nsf.gov

Co-Investigators

Winslow Briggs, University of California, Santa Cruz 650-325-1521 briggs@stanford.edu

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent federal agency that

supports fundamental research and education across all fields of science and

engineering, with an annual budget of $6.06 billion. NSF funds reach all 50

states through grants to over 1,900 universities and institutions. Each year,

NSF receives about 45,000 competitive requests for funding, and makes over

11,500 new funding awards. NSF also awards over $400 million in

professional and service contracts yearly.

Get News Updates by Email Get News Updates by Email

Useful NSF Web Sites:

NSF Home Page: http://www.nsf.gov

NSF News: http://www.nsf.gov/news/

For the News Media: http://www.nsf.gov/news/newsroom.jsp

Science and Engineering Statistics: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards Searches: http://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/

|