|

Discovery

How Desert Dust Feeds the World's Oceans

Scientists sample dust and trace metals in seawater to learn more about climatic change

May 9, 2008

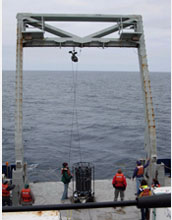

In mid-February, at the height of Austral summer, the sun in the Antarctic never sets. Nor did the work ever stop for University of Hawaii oceanography professor Chris Measures and his team of trace-metals oceanographers, who worked around the clock measuring dust from the decks of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography research vessel (R/V) Roger Revelle. The researchers affixed bouquets of trumpet-shaped filters to the ship's mast to trap dust from the air. And for every degree of longitude, they sampled the sea, plunging a contraption of cylindrical bottles to the depths of the upper ocean, screening the water for remnants of dissolved dust and the trace amounts of iron and aluminum they contain. Measures is taking part in a leg of the Climate Variability and Predictability (CLIVAR) and Carbon research programs called the Repeat Hydrography program, a series of cruises funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) seeking to document and comprehend the ocean's role in climate change. CLIVAR research cruises have surveyed representative sections of the ocean on a decadal scale since the 1990s, focusing primarily on better understanding the carbon cycle. In collaboration with William Landing at Florida State University, Measures is running an adjunct program for trace metals on the CLIVAR cruises. Since receiving NSF support in 2003, Measures and Landing have led dust-measuring teams on six CLIVAR cruises in the Atlantic, Pacific, Southern and Indian oceans. Which all begs the question, what exactly does dust have to do with carbon? Unlike land plants, aquatic plants can permanently remove carbon dioxide from atmospheric circulation. Some sink to the ocean floor after death, and the carbon in their bodies remains subsumed in the deep ocean for thousands of years. Dust, as a process, holds a place in the ocean carbon cycle as a source of iron for those plants. As chemical oceanographers, Measures and Landing are interested in how chemicals enter and cycle through the oceans. They are particularly interested in iron, a micronutrient necessary for plant growth. Just as pill supplements are a way to get vitamins into human bodies, dust from continental deserts is one way to get iron into the oceans, where phytoplankton use the dissolved form of iron, along with inputs like carbon dioxide, to process sunlight and make food for themselves. In quantifying dust deposition, the researchers hunt for trace amounts of iron and aluminum in the water column. Aluminum is not directly used by plants, but it exists in proportion to iron in desert dust, and its presence in the oceans shows the origins and the paths of iron, long after the iron has been absorbed by plants. For all the effort the researchers spent collecting water and running samples in their shipboard laboratory, not much iron or aluminum was to be found off of Antarctica. Even by trace metal standards, where concentrations are measured in nanograms (billionths of a gram) per liter, there were only the slightest traces of iron. Low iron levels have long been suspected of limiting productivity in the Southern Ocean; as a region, it has an unusual excess of general nutrients that are, in most oceans, completely consumed by plants. It's not the amount of iron that matters to Measures' team, so much as what the existing iron can illuminate about process. While inland Antarctica receives rains sparse enough to qualify it as the world's largest desert, much of the continent's dirt is locked under ice, and prevented from becoming dust. What iron exists in these waters comes from two additional sources. In shallow sections, iron may be churned up from underwater plateaus and continental shelves. Throughout the ocean, iron can be recycled from the breakdown of dead materials. Knowing the sources of iron, and how much each contributes, helps in creating accurate climate prediction models. Given the dearth of iron in the Southern Ocean, some have even suggested adding a fourth, artificial source of iron. Earlier this fall, a conference at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution spotlighted "iron-seeding" as a potential vehicle for carbon sequestration. The theory is simple: dump iron in the ocean where plant productivity is iron-limited, and it will encourage plant growth. More plants would take in more carbon dioxide and, on death, more carbon dioxide will sink out of the reach of atmospheric circulation. While greater ocean productivity has coincided with major drops in CO2 during past ice ages, iron-seeding experiments are so far yielding more caveats than green lights. Adding iron has stimulated plant production, but it has also altered other parts of the biological pump. In iron-saturated conditions, for instance, the dominant phytoplankton use less silica; being lighter, they sink less directly, throwing off the efficiency of the carbon pump. Some members of CLIVAR's trace metals team have worked on iron-seeding experiments, but their work on CLIVAR cruises focuses on the existing world. From the CLIVAR series, and from an upcoming cruise series for chemists called GEOTRACES, Measures, Landing and their colleagues are pooling efforts to create an unprecedented map that shows the distribution of chemicals in the oceans. For weeks, the team plodded through their time at sea. They raised and lowered the air filters in a daily ritual, and ran vials of seawater through yards of plastic tubing. They warmed their stiff fingers over mugs of espresso, entranced by a perpetual dusk that faded to blue-black nights as they steamed north. Every so often, they found minute traces of earth metals which, while invisible, hold one in a set of many keys to understanding how people are changing the planet. -- Pien Huang, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Pien.Huang@gmail.com This Behind the Scenes article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

Investigators

Chris Measures

William Landing

Related Institutions/Organizations

University of Hawaii

Florida State University

Locations

Atlantic Ocean

Pacific Ocean

Southern Ocean

Indian Ocean

Florida

Hawaii

Related Programs

Chemical Oceanography

Antarctic Organisms and Ecosystems

Antarctic Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences

Related Awards

#0752609 Collaborative Research: Participation in the GEOTRACES Intercalibration Cruise

#0649584 Collaborative Research: Global Ocean Survey of Dissolved Iron and Aluminum and Aerosol Iron and Aluminum Solubility Supporting the CLIVAR Repeat Hydrography Project (2007-2009).

#0443403 Collaborative Research: Plankton Community Structure and Iron Distribution in the Southern Drake Passage and Scotia Sea

#0326633 Collaborative Research: Sampling and Analysis of Iron, an International Collaboration

#0230445 Collaborative Research: Plankton Community Structure and Iron Distribution in the Southern Drake Passage

#0223397 Collaborative Research: Global Ocean Survey of Dissolved Iron and Aluminum and Aerosol Iron and Aluminum Solubility Supporting the Repeat Hydrography (CO2) Project

Total Grants

$2,216,630

Related Agencies

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Related Websites

LiveScience.com: Behind the Scenes: How Desert Dust Feeds the World's Oceans: /news/longurl.cfm?id=60

LiveScience Video: Dust Hunters: /news/longurl.cfm?id=61

|