Special Report:

Accessible Public Rights-of-Way

Planning and Design for Alterations

PDF version

August 2007

This report and its recommendations are the work of a subcommittee of the Public Rights-of-Way Access Advisory Committee (PROWAAC) and are intended to provide technical assistance only. The report is not a rule and has no legal effect; it has not been endorsed by the U.S. Access Board, the Department of Justice, or the Federal Highway Administration of the Department of Transportation.

Public Rights-of-Way Access Advisory Committee (PROWAAC)

Subcommittee on Technical Assistance

Jerry Markesino, PROWAAC Chair, Portland, OR

Janet Barlow, TAM Subcommittee Chair, Atlanta, GA

Document Produced by Otak, Inc. |

|

|

Table of Contents

ABBREVIATIONS

AASHTO—American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials

ADA—Americans with Disabilities Act

ADAAG—ADA Accessibility Guidelines

APS—Accessible Pedestrian Signal(s)

APWA—American Public Works Association

CIP—Capital Improvement Program

DOJ/USDOJ—United States Department of Justice

DOT/USDOT—United States Department of Transportation

DWS—Detectable Warning Surfaces

FHWA—Federal Highway Administration

ITE—Institute of Transportation Engineers

MUTCD—Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices

NCHRP—National Cooperative Highway Research Program

PAR—Pedestrian Access Route

PBIC – Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center (http://www.pedbikeinfo.org), an FHWA grantee/

transportation institute at the University of North Carolina. The PBIC is made up of the core staff of

professionals at the UNC Highway Safety Research Center, including engineers and planners who are

knowledgeable on walking and bicycling issues.

PROWAAC—Public Rights-of-Way Access Advisory Committee

PROWAG—Draft Proposed Right-of-Way Accessibility Guidelines

STIP—State Transportation Improvement Program

STP—Surface Transportation Program

TIP—Transportation Improvement Program

Title II—ADA implementing regulation for title II, as printed in the Federal Register (7/26/91).

The Department of Justice’s regulation implementing Title II, Subtitle A, of the ADA, which prohibits

discrimination on the basis of disability in all services, programs, and activities provided to the public by

State and local governments, except public transportation services (which are covered by Subtitle B, the DOT

regulation).

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

by Mary O'Connor, Transportation General Manager, City of Scottsdale, AZ; Barbara McMillen, Pedestrian Accessibility Specialist

The Public Right-of-Way

The public right-of-way is a complex space serving multiple users and functions. The sidewalk and street crossing network is the basic unit of pedestrian mobility and its surfaces support all of us—from children to elders—in both pleasant and inclement weather. Private, transit, and commercial vehicles vie with pedestrians for right-of-way width. All modes of travel, including motor vehicles, rail transit, and foot traffic share time and space at intersections. Power companies maintain above-ground and below-ground transmission lines; municipalities own and operate surface streets and sidewalks; and utility companies and public agencies oversee below-grade sewers, water mains, gas mains, and data and telecommunication networks. The public right-of-way in large cities may include both air rights and underground circulation routes used by pedestrians. Adjacent to the right-of-way, private property owners construct, maintain, and operate buildings, entries, driveways, sidewalk vaults, basements, and other improvements and expect usable connections to and from public sidewalks and streets.

Over the last decade, roadway design principles have been expanded to include pedestrian travel accommodations that are increasingly being sought in residential neighborhoods and commercial centers in suburban and urban development. Designs are now expected to reflect equity and context and to balance pedestrian and vehicular use. The design pedestrian is now understood to be not an individual but a range of users—children, elders, people pushing or pulling strollers and delivery carts, using a wheelchair or scooter, or traveling with a long/white cane or a service animal—for all of whom the roadway and pedestrian environment must function effectively. Many of right-of-way users are people whose independent mobility requires pedestrian travel; they are best served by a network of accessible facilities that can provide efficient and safe route choices for a wide range of trip types.

| |

|

| |

Photograph of a sidewalk widened to go around an obstruction. |

Our extensive system of existing roadways is constantly being improved. The vast majority of work in the public right-of-way environment is reconstruction, alteration work, not new construction. The bulk of public works funds are used to maintain and to make changes in those existing environments, rather than to create new facilities. Each altered element must be accessible to and usable by people who have disabilities, to the maximum extent feasible. Integrating accessible features in planned alterations projects requires an understanding of both regulatory and usability concepts. This technical assistance publication has been developed to provide guidance in the planning and design of pedestrian improvements constructed as part of an alteration project. Its text, illustrations, and case studies aim to expand the reader's body of knowledge in accessible right-of-way design.

Accessibility Regulations

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 is a civil rights statute that prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities. ADA implementing regulations for Title II prohibit discrimination in the provision of services, programs, and activities by state and local governments. Designing and constructing pedestrian facilities in the public right-of-way that are not usable by people with disabilities may constitute discrimination. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (504) includes similar prohibitions in the conduct of federally-funded programs.

Thus, the accessibility objective in a new project is to design and build facilities that are ‘readily accessible to and usable by' people with disabilities. Compliance is measured against the referenced standards. From the ADA Title II implementing regulation:

(c) Accessibility standards. Design, construction, or alteration of facilities in conformance with [UFAS] or [ADAAG] shall be deemed to comply with the requirements of this section with respect to those

facilities …

|

|

The PROWAAC Committee at its January 2001 presentation of its recommendations for new PROW guidelines, “Building a True Community.” |

|

Furthermore, equivalent facilitation—achieving accessibility's objectives by other means than are described in the standard—is recognized:

… Departures from particular requirements of either standard by the use of other methods shall be permitted when it is clearly evident that equivalent access to the facility or part of the facility is thereby provided.

However, ADA standards for new construction and alterations promulgated (as guidelines) by the U.S. Access Board and adopted by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) in 1991 were principally developed for buildings and site work and are not easily applicable to sidewalks, street crossings, and related pedestrian facilities in the public right-of-way. Similarly, Section 504 standards (UFAS or ADAAG for USDOT, depending on the agency) did not offer guidance appropriate for rights-of-way construction. The need to address rights-of-way accessibility in a more specific way is apparent from the difficulties practitioners and agencies have in applying ADAAG to this very different environment.

Progress Towards Accessibility Standards for New Construction and Alterations in the Public Right-of-Way

The Access Board is the Federal government's specialist in accessible design. Under the ADA, the Board is responsible for developing the minimum accessibility guidelines needed to measure compliance with ADA obligations when new construction and alterations projects are planned and engineered.

In 1999, the Access Board started the rulemaking process for accessible pedestrian facilities in public rights-of-way by convening a Federal advisory committee of key stakeholders to develop recommendations that could supplement or replace the current standard. The Public Rights-of-Way Access Advisory Committee (PROWAAC) completed its initial work in 2000 and published its recommendations for new guidelines in a report, Building a True Community, which was presented at the 2001 Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting.

Resource: PROWAAC Report at:

http://www.access-board.gov/prowac/commrept/index.htm.

On June 17, 2002, the Access Board issued a Notice of Availability of Draft Public Rights-of-Way Accessibility Guidelines (PROWAG) based on the PROWAAC report. Comments from consumers and design professionals led to the issuance of a second draft on November 23, 2005. A Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) will follow seeking public comment prior to publication of a final rule.

Resource: November 23, 2005 draft PROWAG at:

http://www.access-board.gov/prowac/draft.htm.

The DOJ and U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) are authorized by law to adopt standards consistent with the Access Board's guidelines for use in enforcing the ADA. The DOT has a similar authority under its Rehabilitation Act/504 regulation. The DOJ reviews 504 regulations issued by Federal agencies. When standards consistent with the final PROWAG guidelines are adopted by the DOJ, they will become the new minimum design standards under the ADA for both new construction and alterations of pedestrian facilities in the public right-of-way. The DOT has already indicated its intent to adopt the PROWAG, when completed, into its 504 standard.

In the interim, jurisdictions must continue to design and construct new and altered pedestrian facilities that are accessible to and usable by people with disabilities. The 2005 draft PROWAG has been identified by DOT as the current best practice in accessible pedestrian design under the Federal Highway Administration's Federal-aid (504) regulation.

Resource: FHWA Memorandum of January 2006 at:

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/bikeped/prwaa.htm .

|

|

|

San Francisco uses plywood curb ramps with edge protection for temporary sidewalk detours. Here PROWAAC member Ken Stewart of CCLVI (with white cane) tests a model while Lukas Franck of The Seeing Eye looks on. |

Following completion of Building a True Community, the Access Board asked PROWAAC to develop guidance and recommendations focused on achieving accessibility in alteration projects within the public right-of-way. This advisory, Special Report: Accessible Public Rights-of-Way—Planning and Designing for Alterations, compiles the recommendations of a subcommittee of PROWAAC that worked to develop and highlight model rights-of-way design alternatives, design processes for making alterations, design solutions to specific problems, and case studies demonstrating examples of accessible design practices from across the country.

Alterations

The focus of this report is on improvement projects in the public right-of-way that are classified as alterations under the ADA.

Alterations are discretionary changes, which the agency chooses to fund, to existing facilities within an already-developed right-of-way where the work affects, or could affect, the usability of that facility. ADA Title II implementing regulations require that each part of a facility altered by, on behalf of, or for the use of a public entity after January 26, 1992, be designed and constructed so that the altered parts are readily accessible to and usable by individuals with disabilities to the maximum extent feasible. While the following quote is from the ADA Title III regulation, it is a useful explanation of alteration and existing facilities.

b) Alteration. For the purposes of this part, an alteration is a change to a […] facility that affects or could affect the usability of the building or facility or any part thereof.

(1) Alterations include, but are not limited to, remodeling, renovation, rehabilitation, reconstruction, historic restoration, changes or rearrangement in structural parts or elements, and changes or rearrangement in the plan configuration of walls and full-height partitions. Normal maintenance, reroofing, painting or wallpapering, asbestos removal, or changes to mechanical and electrical systems are not alterations unless they affect the usability of the building or facility.

(2) If existing elements, spaces, or common areas are altered, then each such altered element, space, or area shall comply with the applicable provisions of appendix A to this part.

(c) To the maximum extent feasible. The phrase “to the maximum extent feasible,'' as used in this section, applies to the occasional case where the nature of an existing facility makes it virtually impossible to comply fully with applicable accessibility standards through a planned alteration. In these circumstances, the alteration shall provide the maximum physical accessibility feasible. Any altered features of the facility that can be made accessible shall be made accessible. If providing accessibility in conformance with this section to individuals with certain disabilities (e.g., those who use wheelchairs) would not be feasible, the facility shall be made accessible to persons with other types of disabilities (e.g., those who use crutches, those who have impaired vision or hearing, or those who have other impairments).

All state and local government entities are covered by this requirement. Regardless of whether state or local governments directly manage or delegate the development of facilities in the public right-of-way to the private sector, the same obligations apply.

Federal-aid facilities covered by 504 regulations follow a somewhat different approach, relating the scope of required accessibility improvements in an alteration to the scope of the overall project. When PROWAG is final, it is expected that FHWA Federal-aid regulations will be changed to reference the new document.

The Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987 clarified that all programs and activities of Federal-aid recipients, subrecipients, and contractors are covered by 504 requirements. From a 1992 FHWA memo:

The efforts to prevent discrimination must address, but not be limited to, a program's impacts, access, benefits, participation, treatment, services, contracting opportunities, training opportunities, investigations of complaints, allocations of funds, prioritization of projects, and the functions of right-of-way, research, planning, and design.

Existing Facilities

Requirements for existing facilities and programs are stipulated in the DOJ ADA Title II regulation and the DOT/FHWA section 504 regulation. They apply a separate obligation for ‘program access' to existing facilities not otherwise being altered. From DOJ's ADA Title II technical assistance manual:

The Title II regulations impose a more generalized standard with respect to facilities covered by the ADA that were in existence in January 1992. Rather than applying the accessibility requirements to “[e]ach facility” that is covered (28 C.F.R. 35.151(a)), the regulations provide that a “public entity shall operate each service, program, or activity, so that the service, program, or activity, when viewed in its entirety, is readily accessible to and usable by individuals with disabilities.” 28 C.F.R. 35.150(a) (emphasis added). In addition, the regulations further provide that, even under this “entirety” approach, a public entity is not required “to take any action that it can demonstrate would result in * * * undue financial and administrative burdens.” 28 C.F.R. 35.150(a)(3).

The regulation governing existing facilities also provides that any “structural changes to facilities” necessary to comply with title II were to be made in accordance with a transition plan. 28 C.F.R. 35.150(d)(1). In particular, the regulation provides that such a “transition plan shall include a schedule for providing curb ramps” on “walkways” controlled by the public entity, “giving priority to walkways serving entities covered by the Act, including State and local government offices and facilities, transportation, places of public accommodation, and employers, followed by walkways serving other areas.” 28 C.F.R. 35.151(d)(2).

In assessing and addressing their responsibilities for existing facilities, many jurisdictions have relied heavily on two helpful tools—the self-evaluation and the transition plan. These tools were initially required under both 504 and ADA Title II regulations. Many jurisdictions have continued to use these tools to plan for addressing accessibility issues, assessing progress, and managing changing circumstances. In addition, DOT's 504 regulation requires that jurisdictions establish a system for periodically reviewing and updating the self-evaluation that forms the basis for the Federal-aid transition plan.

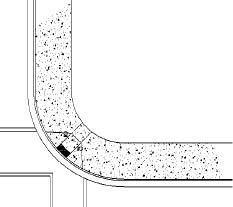

| |

|

| |

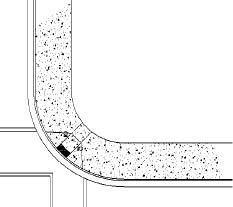

An urban intersection with paired perpendicular curb ramps, each with a 2-foot strip of detectable warnings at the toe. The flares have been shortened so that the ramps will both fit on the corner (flares are not a part of the pedestrian access route.)

|

A transition plan can provide decision-makers with an efficient tool for complying with section 504 and ADA requirements and holds information that often is not available in other planning documents. An updated transition plan will identify and locate elements and features that need to be added or altered, processes for determining accessibility priorities, and information that can be used in assessing the ‘undue burden' cost limitation in existing facilities. Cost is not a determinant in new construction and alterations.

While many methods may be utilized to achieve program access in existing facilities, ensuring usability in an already-developed pedestrian circulation system (a program) is likely to require remedial construction. In some cases, a new construction or alterations project will give rise to a program access obligation, as, for example, when a bus stop sign is placed in a hitherto-undeveloped environment. The presence of an existing bus stop that is not yet served by the pedestrian facilities needed to make it accessible—a pad for the deployment of a bus lift, a sidewalk for access to the stop—is a clear indicator of program access improvements that may need to be constructed for full use of the transportation system. It makes good economic and civil rights sense to look broadly at both responsibilities when new work is being planned and engineered.

Resources: DOJ's ADA title II regulation at:

http://www.ada.gov/reg2.html;

and a technical assistance manual at:

http://www.ada.gov/taman2.html;

DOJ's ‘Best Practices Toolkit for State and Local Governments' at:

http://www.ada.gov/pcatoolkit/toolkitmain.htm;

FHWA 504 regulation at:

http://www.fta.dot.gov/civilrights/ada/civil_rights_3907.html;

DOT planning documents at:

http://www.planning.dot.gov/documents/BriefingBook/BBook.htm;

DOT technical assistance at:

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/civilrights/ada_memo_clarificationa.htm;

DOT memo on the Civil Rights Restoration Act at:

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/legsregs/directives/notices/n4720-6.htm.

The following chapters provide an overview of alterations projects from a regulatory and practical perspective. We hope it will help you implement accessible and usable pedestrian facilities under the most stringent of conditions—within the constraints of existing developed streetscapes. We include useful information on the planning and pre-design process for public right-of-way alteration projects; engineering drawings illustrating typical barriers in a range of roadway conditions; case studies of real-world solutions to access constraints; plans that demonstrate how accessible features can be incorporated into sidewalks of varying widths; model curb ramp examples; and resources from local, state, and Federal agencies.

This guidance has been drawn from expert practitioners across the U.S. and is focused entirely on improvement projects in the public right-of-way that can be considered alterations under the ADA. The design process for making accessibility improvements in alteration projects is not any different from the design process for traditional street modification projects. It involves the same use of standards, technical guidance, and product information that designers follow in every roadway design project. One key to success: recognition that ADA design standards are minima and maxima describing a range rather than design or engineering objectives. The running slope of a complying curb ramp may range between 0 and 1:12, but we suggest that designers set their calculations to fall within that range, not at its extreme, lest a construction or other anomaly affect compliance.

Case Study Examples

Throughout this Special Report are case study examples that illustrate alteration challenges and solutions applied to these challenges. Comments are provided to clarify the particular application and to provide the reader with background conditions to better understand the solution. Look for case study examples in a box similar to this one.

Case Study—Narrow Right-of-Way

-

A midblock crossing and perpendicular curb ramp are aligned with an existing building entrance walkway. The walkway serves as the level landing for the curb ramp and the work was coordinated with the abutting property owner.

- Pedestrians can use the landing to bypass the descending ramp and its flares if they are continuing along the sidewalk.

- The midblock crossing has a pedestrian signal with a call button and an APS with a locator tone.

- Still needed: detectable warnings at the street edge.

|

Case Study—Narrow Right-of-Way

- The roadway travel lane was narrowed to add width to the pedestrian sidewalk and to accommodate the relocated parking meters.

- At the corner, a curb extension (bulb-out) into the parking lane provides the necessary space for a curb ramp and landing.

- The curb radius was omitted at this non-turning corner.

- Still needed: detectable warnings at the street edge.

|

Case Study—Downtown Redevelopment

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

The before photo (above) is a downtown streetscape in Pottstown, PA that was the subject of an improvement project to invigorate downtown retail, add bike lanes, and increase parking. The after photos (left) show the changes: new angled parking, bike lanes and more visible markings. |

|

|

- The project required other improvements that offered opportunities for increased access: re-striping, new controllers and vehicle and pedestrian signals (existing equipment did not meet new MUTCD standards), and new curb ramps where bulb-outs were added.

- New accessible parking spaces were located near intersections to take advantage of the curb ramp serving the crossing.

|

Case Study—Work Zone Accessibility Case Study—Work Zone Accessibility

- The photograph shows a same-side temporary pedestrian route that bypasses construction on the sidewalk.

- Plywood surfacing is used where the route crosses grassy terrain; the joint is highlighted with contrasting paint. Still needed: a better bevel at the joint.

- The edge of the plywood walkway provides an adequate wayfinding cue on the opposite side (it provides good sound-on-cane information.) Chain link fencing is poor as a channelization enclosure, since it is not easy to follow with a cane and usually requires ‘feet' that narrow the walkway.

|

CHAPTER 2: ALTERATIONS

by Jerry Markesino, PE, Otak, Inc.; Michele Ohmes, APWA

| |

|

| |

This urban alteration to replace a block of sidewalk and curbing is constrained by right-of-way width, existing adjacent entrances, and the presence of a bus stop requiring a deployment area for a lift. At pedestrian crossings, the project must incorporate (or improve, as feasible) curb ramps. Note that print signage and plastic tape do not adequately protect the excavation—a detectable barrier is needed. Consider also a proximity-activated ‘audible sign' to give notice of the blocked sidewalk. These are available from several barricade manufacturers and can be locally recorded with a specific detour message.

|

Alteration projects in the public right-of-way present particular challenges because of the limits of width and grade already established in the existing developed environment. Doorways cannot be readily changed because the threshold elevation is linked to the finished floor elevation of the building, which is not part of the project scope. Underground vaults and utility services cannot easily be relocated. Mature trees cannot be moved and will die if adjacent grade is raised or lowered or root growth is affected by construction. A railroad overpass pinches a narrow roadway and leaves no space for sidewalks to be added. Accessibility features that can easily be provided in the course of a new construction project are more difficult to incorporate in alterations because of such physical constraints.

An alteration project may differ from a new construction project because of existing development, which limits available space and has fixed access points and elevations that must be addressed. Where existing constraints in an alteration project prevent the full implementation of accessibility objectives (whether measured by appropriate standards, where they exist, or by usability if they do not), the ADA and 504 regulations provide a degree of flexibility to designers and agencies. From the ADA Title II regulation:

35.151 New construction and alterations. (b) Alteration. Each facility or part of a facility altered by, on behalf of, or for the use of a public entity in a manner that affects or could affect the usability of the facility or part of the facility shall, to the maximum extent feasible, be altered in such manner that the altered portion of the facility is readily accessible to and usable by individuals with disabilities, if the alteration was commenced after January 26, 1992.

Here is the text on infeasibility in alterations projects from the ADA Standards (Section 4.1.6 (j) of Appendix A, 28 CFR Part 36):

(j) EXCEPTION: In alteration work, if compliance with 4.1.6 is technically infeasible, the alteration shall provide accessibility to the maximum extent feasible. Any elements or features of the building or facility that are being altered and can be made accessible shall be made accessible within the scope of the alteration.

Technically Infeasible. Means, with respect to an alteration of a building or a facility, that it has little likelihood of being accomplished because existing structural conditions would require removing or altering a load-bearing member which is an essential part of the structural frame; or because other existing physical or site constraints prohibit modification or addition of elements, spaces, or features which are in full and strict compliance with the minimum requirements for

Note that cost is not a trigger of infeasibility in alterations.

Since alterations under the ADA are required to meet new construction criteria to the maximum extent feasible, extensive reconstruction work can and should approach the accessibility required of new construction. For example, a project that calls for the removal of pavement and sidewalks to subgrade, followed by the installation of new walks and pavement, is an alteration whose broad scope offers significant opportunity to incorporate the full range of accessible features. On the other hand, the installation of a single curb ramp at an existing intersection is an alteration with limited scope for correcting adjacent inaccessible conditions.

Terminology

In the transportation industry, construction work may be classified as new construction—the installation of improvements where none currently exist—or reconstruction. State agencies often use ‘4R' terminology: reconstruction, rehabilitation, restoration and resurfacing. Local agencies may refer to reconstruction work as modification, renovation, upgrading, rebuilding, and modernization. Federal highway agency nomenclature relies on new construction, reconstruction, and ‘3R (resurfacing, rehabilitation, and restoration of pavements)'. Whatever term is used, the removal of some existing improvements and installation of replacement improvements constitutes an alteration under the ADA.

The reconstruction of a roadway, the upgrading of a sidewalk, or the installation of other elements are alterations when they affect usability, temporarily or permanently, for pedestrians or vehicles. Transportation agencies may consider resurfacing a roadway a maintenance item, for ADA purposes it has been considered an alteration with respect to the special Title II obligation at 35.151(e) to install curb ramps.

Resources: Yerusalim at:

http://www.access-board.gov/prowac/yerusalim.htm

DOJ ‘Common Problems' at:

http://www.ada.gov/comprob.htm

Project Civic Access Agreements at:

http://www.ada.gov/civicac.htm

Memorandum Clarifying FHWA Oversight Role in Accessibility at:

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/civilrights/ada_memo_clarificationa.htm

FHWA Questions and Answers About ADA and Section 504 at:

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/civilrights/ada_qa.htm

FHWA Memorandum on Detectable Warning Requirements at:

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/bikeped/dwm.htm

Curb Ramps

Under the ADA, an alteration to a sidewalk or street will give rise to an additional obligation to include curb ramps in the scope of the project. From the Title II regulation:

35.151(e)(2) Curb Ramps. (1) Newly constructed or altered streets, roads, and highways must contain curb ramps or other sloped areas at any intersection having curbs or other barriers to entry from a street level pedestrian walkway. Newly constructed or altered street level pedestrian walkways must contain curb ramps or other sloped areas at intersections to streets, roads, or highways.

In addition, the Title II regulation requires that jurisdictions prepare and implement a curb ramp schedule for their existing facilities, subject to certain time and cost limits:

35.150(d)(2) Transition plan. If a public entity has responsibility or authority over streets, roads, or walkways, its transition plan shall include a schedule for providing curb ramps or other sloped areas where pedestrian walks cross curbs, giving priority to walkways serving entities covered by the Act, including State and local government offices and facilities, transportation, places of public accommodation, and employers, followed by walkways serving other areas.

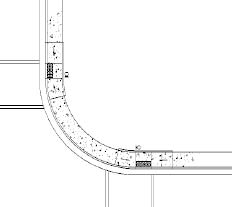

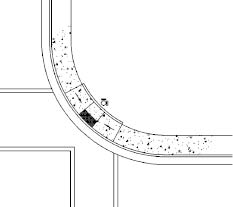

| |

|

| |

This new parallel curb ramp on a large-radius suburban corner curves down to the street and is otherwise usable, but the pedbutton isn't. Installed on a signal pole, it is out of horizontal reach range for this pedestrian. A better installation can be seen across the street, where a stub pole has been installed in a more usable location.

|

Project Physical Constraints

Since alteration projects are always constructed within an existing developed environment, there will always be existing facilities to deal with. Roadways, sidewalks, trees, utilities, adjacent private improvements, street lights, traffic signals, and a multitude of other facilities are already there. When one of the items is identified for reconstruction, it is likely that other facilities will be involved. This is simply the nature of this type of work.

Depending on the scope of the project, these existing facilities need to be considered in the project design. In some cases, desirable changes can be included with a small expansion in project scope and designed and built with little impact on the primary project. In other cases, removal of barriers to program access or correction of inaccessible adjacent construction should remain outside the scope of work.

Existing facilities can become physical constraints that impose a limit on the extent of any right-of-way improvement. When a new streetcar trackway is being planned, the preferred alignment may lie directly over a shallow steel water main. If the trackway is built over the water main, the electric powered train will discharge power to the ground and cause corrosion to the water pipe. After a few years of operation, the electrical discharge will destroy the water main. A decision must be made to either realign the trackway or rebuild the water main and protect it from being destroyed by the electrical discharge. In this case, the water main has become a physical constraint that imposes limitations on the streetcar project, perhaps requiring an expansion in the project scope of work.

| |

|

| |

Ooops! Where's the wheelchair accessible route? Much better coordination is needed at this urban bus shelter location. Even though the sidewalk width is generous, tree boxes crowd the shelter on either side and a fixed trash can on one side and the bus stop sign on the other complete the job—it looks good but isn't usable because there's no pedestrian access route or pad of sufficient size to deploy a bus lift. The bicycle chained to the sign is the last straw! Best fix: move the trash can and bus stop sign.

|

In another example, an additional travel lane is proposed in the project scope and existing street trees occupy the space needed for the travel lane. The trees are a physical constraint. However, the scope of the project requires a new travel lane. It is likely that the trees will need to be removed. In this case, the tree removal and new tree planting elsewhere becomes part of the scope of the project. Ensuring that pedestrian facilities are accessible is just as important as meeting roadway design and operational guidelines. Where existing physical constraints are encountered, the project design should deal with them and deal with them in ways that are commensurate with the overall undertaking. For example, sight distance obstructions that affect intersection safety are routinely removed in an intersection modification project. Likewise, physical constraints that affect sidewalk usability should also be handled as a routine design practice.

When existing physical conditions affect the feasibility of achieving full conformance with accessibility criteria in an alteration, the design engineer should determine, on an element-by-element basis, what degree of usability can reasonably be achieved within the scope of the planned project.

The challenge of dealing with project physical constraints in alteration projects has been recognized by the authors of accessibility standards for years. In 1992, in the development of proposed regulations, the Access Board identified a number of possible physical constraints that might bear on the feasibility of certain accessibility features, including:

- the existence of an underground structure, such as a utility vault, manhole, or sewer inlet at a street crossing that may preclude the installation of a new public sidewalk curb ramp in full compliance with provisions for new construction;

- the geometric design of existing roadways, bridges, or tunnels constrained by structural elements that, even when altered, may not accommodate a public sidewalk with adequate width for wheelchair users;

- differences in finished grade at curbside and elevations at existing building entrances at the back-of-sidewalk that may preclude compliance with cross slope provisions across the entire public sidewalk width;

- existing fixed equipment, such as fire hydrants or street lighting standards, located on a public sidewalk and connected to below-grade water, power, signal, and similar distribution systems that may prevent full compliance with public sidewalk curb ramp provisions if the equipment cannot be relocated in the course of the work;

- existing narrow public si dewalks or rights-of-way that might preclude the maintenance of a continuous passage free of gratings required for new subway construction; or

- the existence of an established landscaping feature, such as a large tree or grouping of trees that may preclude the provision of a parallel access aisle at a newly-established on-street parking space. Furthermore, a pre-existing commercial use of the public sidewalk, as for a sidewalk café, may also constitute a physical constraint if no other location for an accessible parking space is feasible within the scope of the alterations project.

Public agencies and designers need to be creative and flexible in developing solutions that promote accessible travel. Adjusting the geometrics in an existing system takes a greater degree of creativity, thought, and engineering know-how than when starting from scratch on a new project.

An understanding of accessibility criteria and rationale, skills enhanced from engineering study, and design experience with accessible facilities will enable practitioners to develop and deploy a toolbox of approaches appropriate to a wide range of project conditions. Designers should consider the entire right-of-way that is available as they work to balance facilities between vehicle, bicycle, and pedestrian use.

| |

|

| |

Plenty of street width is available for an imaginative solution to curb ramp installation at this small town intersection. Open culverts extend several feet from the curb at cross streets and are bridged with concrete ramps, open below for drainage, and handrails for edge protection. Beginning at the top of the curb almost 15 inches above road grade, these flying ramps both protect the culvert and provide access to the crosswalk. Edge protection is needed, however, and detectable warnings at the street edge.

|

Resources:

AASHTO: “A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets”, 2004;

“Guide for the Planning, Design, and Operation of Pedestrian Facilities”, 2004: bookstore at https://bookstore.transportation.org/;

FHWA: “Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices”, 2003 http://mutcd.fhwa.dot.gov

Desirable objectives in the public right-of-way include curb ramps that are flatter than a 1:12 slope; adjacent landings that are near-level; signal call buttons within easy reach ranges of a person who uses a wheelchair; equipment installations that accommodate the techniques of low-vision and white cane travel; and crossing information that is usable by all pedestrians. Armed with an understanding of the rationale behind accessibility provisions and guidance available in industry documents, the street design professional will be well-prepared for the planning and engineering of alteration projects that include usable pedestrian facilities.

Analyzing Accessibility Alternatives

When physical constraints limit the application of new construction criteria, several potential approaches may be analyzed before selecting the solution that will optimize accessibility. Here is a simple two-step process for making decisions on selecting accessibility alternatives.

[In general, ‘accessible' is used in this document to mean elements or facilities that comply with applicable standards—this is the definition in ADAAG—and ‘usable' to characterize elements or facilities that are not addressed in the standard, which represent equivalent facilitation, or that fall short of full compliance with scoping or technical provisions for new construction. Note that the ADA implementing regulations require new facilities to be both ‘accessible to' and ‘usable by' people with disabilities.]

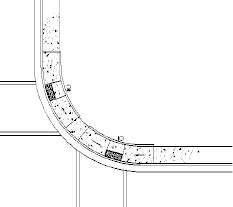

| |

|

| |

This curb ramp retrofit combines a parallel and a perpendicular ramp to stay within running slope limits. Curbed edges provide useful non-visual wayfinding cues. California State provisions (this is in Sacramento) require the corduroy markings at the intermediate landing, but research shows that the truncated domes required at the toe of the ramp (ADAAG 4.7) would provide a significantly more detectable indicator of the upcoming street crossing.

|

First: Consider the use of work-around alternatives that do not affect usability by pedestrians who have disabilities. For example, where there is a problem placing a curb ramp in a preferred location, consider:

- using an alternate form of curb ramp (parallel, combination, or perpendicular);

- identifying an alternate location for the ramp;

- widening the crosswalk to include the curb ramp;

- borrowing space from the parking lane or the roadway;

- adjusting the horizontal and/or vertical roadway geometries;

- extending a curb ramp through the gutter-pan area;

- raising the roadway surface at the gutter;

- lowering the curb height;

- raising the crosswalk;

- adding a curb extension to ‘grab' needed (and often more level) space for pedestrian facilities at corners;

- shielding the sides of a ramp with signs, sidewalk furnishings, and setbacks to eliminate the need for space-intensive flared sides; or

- ramping a sidewalk down to an intermediate level landing.

Second: If an alternative does not meet project constraints, favor approaches that have lesser usability implications. For example:

- modify curb ramp flare space requirements (the flare is not part of the required pedestrian access route [PAR]) or use returned curbs;

- construct a single curb ramp that can do the work of two;

- shave millimeters from a landing or decimals from the running or cross slope of a ramp;

- use a short length of blended or warped sidewalk that can be replaced during a future improvement to connect to existing undisturbed facilities; or

- blend non-conforming pavements in segments that provide as much planarity as possible for the wheelbase of a mobility device (~760 mm x

1220 mm).

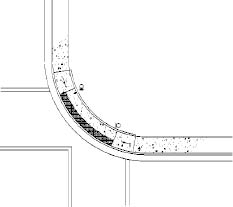

| |

|

| |

Driveway crossings with excessive cross slope are one of the most common problems in alterations projects. Here, an existing driveway apron has been reconstructed to provide a level pedestrian route across it that is narrower than the sidewalk it connects to but adequate for travel over a short distance. In more constrained rights-of-way or where driveway slopes are steeper, a more complex intervention will be needed. Usability can be optimized by ramping the sidewalk down to an intermediate level at the driveway crossing and accepting a lip between apron and roadway.

|

Note that manipulating scoping requirements (one ramp where two will not work, a lesser number of accessible on-street parking spaces where construction is constrained) may also provide needed flexibility in conditions of infeasibility. Equivalent facilitation, obtaining the prescribed ends in another way, is also permitted. For example:

- use of an existing corner curb ramp to serve as an added accessible parking space where sidewalk space is limited;

- use of a leading-pedestrian interval (LPI) or all-red signal to provide crossing opportunities where other timings are not feasible;

- use of a voice message where pedbuttons cannot be separated by the necessary ten feet; or

- use of audible signage where there is insufficient room for tactile text.

The design engineer who is well-versed in accessibility rationale will recognize that some features of accessibility have greater safety and usability effects than others. For example, a lip at the toe of a curb ramp is a significant barrier because users may be crossing at speed, the grade break may be obscured by ponding, and a sudden drop or stop can propel a pedestrian from his or her mobility device. In contrast, the slope or length of a flared side of a ramp is not part of the pedestrian access route, and thus a lack of compliance with the standards is of little significance to usability. A narrow walkway adjacent to an active travel lane requires tighter control of the cross-slope on the sidewalk and curb than does a separated sidewalk set back from the roadway. Level landing areas are critically important where turns must be made.

Project Scope

In the most basic terms, the project scope describes the purpose of the project. The physical constraints of any project are challenges that may make project engineering complex, excessively expensive, or difficult to build. These challenges may require additional funds, cause the scope of work to expand, or kill the project altogether. The scope of work defines a project by answering the questions of What, Why, Where, When, and How. It includes the purpose and justification for the project. It also includes the physical and/or contractual limits of the work. With respect to pedestrian accessibility, the scope of a project must also address the obligations set by ADA Title II and 504 implementing regulations.

The project scope should consider the jurisdiction's transition plan, if one has been prepared. If inaccessible or unusable facilities within the project area have been identified in the transition plan for correction in the future, it is likely that they can most easily be corrected within the scope of the proposed alteration project, as it will generally be more cost effective to correct a known barrier by including it in a planned alteration project rather than wait and fix the problem at a later date. The limitation of project scope or boundary to avoid a program access improvement could give rise to a complaint.

The scope of accessibility improvements should be related to and commensurate with the scope of the overall project, particularly with regard to roadway improvements. Each element that is altered as part of the project must be designed and constructed to be accessible to and usable by people with disabilities to the maximum extent that this is feasible. Failure to provide accessible alteration project improvements may require a public entity, including responsible individuals, to defend their decision-making in court.

How do you know when you've maximized accessibility?

In roadway design, there are many ways to solve a problem. The confidence that a designer has properly applied good engineering judgment in a specific case can only come when accessible design has been fully integrated into the engineer's toolbox.

Designer A develops one solution; engineer B another for the same problem. How can agencies determine which design solution should be used? The U.S. Access Board, the U.S. DOJ, and the U.S. DOT do not approve project designs (or police construction) to ensure that the ‘best' solution is chosen. If the using public believes that a more accessible result might have been achieved, designers may have to defend their decision-making in court. If reasonable care can be demonstrated, then accessible design carries no more risks for public agencies than the design of other roadway features. A few states have a regulatory agency that reviews the design and construction of pedestrian elements to ensure accessibility. They may also have the authority to approve deviations to any state accessibility standards. However, Federal or private litigants are not bound by state or local approvals and may challenge such a decision in a complaint to DOJ or FHWA or an action in court. The best guidance is to approach accessible design and construction with the same care and commitment as all agency initiatives and to document staff training, planning and design procedures, and decision-making processes.

Members of the PROWAAC make the following recommendations:

- Designers need to expand the depth of their analysis and think outside the box.

- Designers should seek assistance from people with disabilities in the community. Consider their opinions and recommendations. Get input, advice, and support from local advisory committees.

- Designers must recognize that the first solution to a problem will not often be the best. Look hard and wide for creative solutions.

- Keep track of everything considered. Document the analysis work, findings, and decisions. Save them in the permanent project record file.

- Select the solution that best balances the needs of all users: people who use wheelchairs, people who have vision impairments, and other pedestrians, young and old. Avoid solutions where roadway improvements are fully realized at the expense of pedestrian accessibility.

- Network with others. Consult with peers in other agencies and firms. Share ideas and solutions.

- Attend continuing education classes that focus on accessible design.

- Develop, adopt, and use a standard method of design review and approval.

- Be prepared to defend your decisions in a potentially adversarial situation.

The recommendations above provide no guarantee that a project design will not be challenged. There will always be someone with a second opinion or a better design solution. However, if the scope of the project is clearly defined, research is adequate, and the method of selecting the preferred alternative is clearly documented, the solution can be adequately defended. It is the designer's responsibility to develop the expertise needed to evaluate potential alternatives before confirming an engineering solution. Note that cost cannot be the basis for eliminating workable alternatives in a planned alteration (however, there is a cost defense related to program access improvements; see 28 CFR 35.150(a)(3) of the Title II regulation).

Project Approach

Engineering judgment is defined in industry literature as the evaluation of available pertinent information and the application of appropriate principles, standards, guidance, and practices for the purpose of deciding upon the applicability, design, operation, or installation of public improvements.

| |

|

| |

In this photo, ITE wayfinding workshop participants work in small groups to develop curb ramp location recommendations based upon intersection corner radius (see the ITE Journal, July 2004).

|

The exercise of engineering judgment directs all the skills of the professional toward the solution of an engineering problem. Accessible pedestrian design practices are only now beginning to develop within the transportation engineering field. Over time, it is expected that a full body of knowledge will be established as the profession takes responsibility for this new aspect of roadway design. Designers should seek out and use currently available resources to assist them in their design efforts. As with any new skill—and this is true for the individual designer as well as for the leadership of the profession—competency in accessible pedestrian design can be gained through education, training, and practice and then be integrated into the current professional skill set. It must be noted that engineering judgement on its own is not a defense against an accessibility complaint.

The design recommendations in this technical assistance manual can help engineers integrate accessible design into the toolbox that is used every day as engineering judgment. However, it is impossible to give guidance specific to every situation, since there are many variables in even the simplest of projects. Seldom will existing conditions be comparable between even two similar projects. It is the intent of this manual to provide an awareness of the rationale behind accessible design provisions, with specific application to alteration projects, and to suggest methods and techniques that will advance current understanding and practice. Particular emphasis has been given to the civil rights concepts that underlie the ADA implementing regulation.

Frequently-asked Questions

When the revised draft guidelines for accessibility in the public right-of-way were published by the Access Board on November 23, 2005, the preamble to the draft (discussion) contained a set of questions and answers intended to help clarify the relationship between the scope of a planned alteration project and related physical constraints. The questions/answers did not address program access requirements (the Access Board mandate is the development of guidelines that can be adopted as Federal standards for new construction and alterations; the Board has no responsibility for ADA provisions governing existing facilities not otherwise being altered).

The same questions are repeated below. The answers have been expanded by the PROWAAC Subcommittee to identify areas where program access requirements may arise, in an attempt to provide a more complete picture of agency and jurisdictional obligations under Title II of the ADA and section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act.

Curb Ramps

1. Question: A multi-block length of roadway is being resurfaced. Existing sidewalk corners have curb ramps, but some of them don't meet current specifications. Must the curb ramps be reconstructed as part of the resurfacing project?

Answer: Resurfacing is considered an alteration and compliant features must be installed to the extent that it is feasible to do so. This work is required by 35.151(e) of the Title II regulation, not by ADA standards for construction, and must be done at the same time as the resurfacing. Discussion: This requirement is analogous to the ‘path-of-travel' requirement for buildings and facilities under which additional work is occasioned by a planned alteration. Curb ramps are the only item of construction specifically required by this provision in Title II, and only as a consequence of an alteration to a roadway or pedestrian walkway. DOJ technical assistance describes resurfacing as an alteration. Kinney vs. Yerusalim, a Federal court decision binding on the Third District, took a similar view, holding that roadway resurfacing constituted an alteration that required the installation of curb ramps. If it is feasible (see the Introduction for the ADA discussion of ‘maximum extent feasible') to provide greater usability/compliance with curb ramp standards, that should be done.

2a. Question: New curb ramps are being installed in an existing sidewalk that is being widened and resurfaced as part of a downtown improvement program. On one corner, an existing underground utility vault is located in the best spot for a curb ramp. Must the utility vault be moved to ensure that the toe of the curb ramp falls within the marked crossing?

Answer: The scope of this project will determine the answer. If utilities are being moved for other reasons within the project scope or limits, it may be feasible to alter or relocate the vault. If planned project construction does not involve the vault, it may not be feasible to locate the curb ramp in as optimal a spot as new construction standards would require. If at some future time the intersection is reconstructed and the utility vault is modified or relocated, there may be an opportunity to locate the curb ramp in the ideal location. Discussion: There are many work-arounds for barriers in the public right-of-way. Consider widening the crosswalk markings to include the new curb ramp location, raising the crosswalk if roadway use permits, or installing an apex ramp as a last resort.

2b. Question: What if the curb ramp can be placed over the vault, but an access cover would have to be located on the curb ramp to do so?

| |

|

| |

In this downtown improvement project in Auburn, AL, splitting the sidewalk allowed two objectives to be served: the upper level provides stepless access to shops and the lower level maintains access to the street. Landscaping, benches, and decorative wrought iron railings separate the two levels, which are connected by a ramp at midblock and blended to a common level at corners. The reconstruction borrowed street space to provide the sidewalk width needed for this imaginative solution in a daunting hilly streetscape.

|

Answer: An access cover on the curb ramp is not prohibited if it conforms to the surface requirements (stable, firm, slip resistant; no changes in level that exceed ADA standards, etc.) for the pedestrian route.

3. Question: One corner of an intersection is being altered by curb and gutter reconstruction to add a curb extension for traffic calming. Paired curb ramps will be installed as part of this project. The other three corners of the intersection are not being altered. Must curb ramps be provided (or improved) at the unaltered corners as part of this work?

Answer: No, although it may be more cost-effective to do so, since most corners should be fitted with curb ramps eventually. Curb ramps within the limits of the project at the altered corner are a required part of this work. Discussion: Existing corners without curb ramps are subject to section 504 and ADA Title II program access requirements; broadening the current project's scope of work to include them now may make good economic sense (unless future construction at other corners is already scheduled).

Sidewalks

4. Question: A project will be undertaken to connect a series of sidewalk segments near a school in support of a Federally-funded Safe-Routes-to-School (SR2S) program. Must the existing segments of sidewalk be modified if they do not meet width or cross slope provisions?

Answer: This is an alteration to an existing pedestrian circulation system and compliant features must be installed to the extent that it is feasible to do so within the scope of the project. Discussion: Since this is an area-wide project intended to provide student circulation routes between homes and school, and not just to link two separated segments of an existing walkway together, the project should be planned to include improvements to existing sidewalk segments that can feasibly be corrected within the scope of a sidewalk improvement project. Students with disabilities cannot be excluded from SR2S programs, which by their nature encourage walking and bicycling, and such programs carry their own program access responsibilities.

5. Question: A new sidewalk is being built along an existing road that contains many driveway access points. Must those driveways be modified if their cross slope exceeds 2%?

Answer: Yes, to the maximum extent feasible within the scope of the project. A new sidewalk, even when constructed as an alteration, must be designed to conform to accessibility standards to the extent that it is feasible to do so. Design guidance from the Access Board includes several driveway apron retrofit schemes (see Case Studies for details).

6. Question: A city is resurfacing a sidewalk along Main Street. The distance between the edge of the right-of-way and the existing roadway does not provide sufficient room for a four-foot-wide pedestrian access route. Does the municipality have to acquire more right-of-way from private property owners or narrow the roadway to provide a more conforming walkway?

Answer: No, accessibility guidelines do not require the municipality to obtain right-of-way or to narrow roadways in the limited scope of work of a sidewalk resurfacing project. However, if a municipality plans to narrow a roadway for traffic-calming purposes or acquire additional right-of-way as part of a downtown improvement project, it should plan the project in such a way as to accommodate new construction standards for sidewalk width. Note that ADA title II regulations will require the addition of curb ramps as part of this project, since it is an alteration to a sidewalk.

Signals

7. Question: Curb ramps are being installed at a signalized intersection as part of a roadway resurfacing project. Existing pedestrian push buttons (pedbuttons) are not accessible or placed in accessible locations. Must the pedbuttons be replaced with accessible models? Must accessible pedestrian signals be installed as part of this project?

Answer: The resurfacing alteration triggers the addition of curb ramps under the ADA Title II regulation. However, there is no requirement to expand the project scope to include other features of accessibility. On the other hand, pedbuttons which are too high, too far from the sidewalk, or are otherwise inaccessible will preclude use by residents with disabilities, raising program access issues. It may be more cost effective to fix them under the proposed project rather than make the improvements at some later date. Discussion: If the pedbuttons are being replaced as part of this project, the new equipment must meet accessibility standards for operating force, reach range, clear ground space, connection to the pedestrian route, etc. Existing pedbuttons may be relocated, subject to installation standards, but if they are of an inaccessible design, it may be a wiser course to replace them rather than risk a program access complaint.

8. Question: The pedestrian signals in a downtown corridor are being replaced with a new system combining WALK/DON'T WALK and count-down signals. Must Accessible Pedestrian Signals (APS) be included in the new system?

Answer: Yes. The installation of a new system is an alteration that must be accessible to and usable by people with disabilities to the maximum extent feasible. APS are widely available. Discussion: When a complete system is upgraded, controller and push button improvements that include APS capability can be added. Providing crossing information in usable formats should be included in the scope of work for a project of this size, complexity, and cost.

9. Question: Count-down signal displays are being added to some existing pedestrian signal heads at an intersection, but the software and signal controller are not being altered. Must APS be installed?

Answer: No, simply adding a display to the existing WALK/DON'T WALK signal would not involve the system changes needed to implement APS. Discussion: Note that program access provisions governing existing facilities may apply at any location, regardless of whether alterations are planned. If a resident with a disability requests APS information at a crossing, a jurisdiction must give consideration to installing them if necessary to provide accessibility. Maintaining a citizen request program, and acting on it, is one way that jurisdictions may satisfy program access requirements for existing facilities not otherwise being altered.

10. Question: An intersection is being signalized and will include APS. The installation of stub poles on the existing sidewalks to mount the new pedbuttons will disturb a limited area of sidewalk. Must curb ramps be installed if none existed?

Answer: No. The scope of this project is to install pedbuttons; it is not an alteration to the sidewalk or the street that would require the installation of curb ramps, as required by the ADA Title II regulation. Discussion: Curb ramps at this location would clearly be required under the section 504 and ADA Title II regulation and should have been included in the agency's transition plan. Their addition is an improvement that might well be scoped and scheduled as a part of this project.

11. Question: The push button on an existing pedestrian signal is being replaced with a sturdier model. Must APS be installed?

Answer: No, but the new push button must conform to applicable accessibility criteria (location, height, operating force limits). Discussion: Modern APS devices are usually integrated into the pedbutton. If every pedbutton at a corner is being replaced as part of this project and controller changes would not be required to support APS, it would be a wise use of public funds to consider APS installation, since a program access need can be anticipated to exist at most locations where pedestrian signals are provided.

12. Question: An intersection with existing sidewalks and pedestrian signals is being widened to include a right-turn lane. Must APS be installed as a consequence of the widening?

Answer: No, installing APS is not within the scope of this project. New pedestrian push buttons installed in the course of the work must meet applicable requirements (or existing ones may be re-installed; see Question 7). However, since this project is an alteration to the street and sidewalk, curb ramps must be installed or improved to the maximum extent feasible.

General

13. Question: The local public transit agency has designated a bus stop by placing a sign in the ground along a roadway that has no sidewalk. Must a concrete or another improved surface be provided in the course of the work?

Answer: No, the placement of a bus stop sign alone does not require other site improvements. However, the designation of the bus stop places future program access responsibilities on the jurisdiction, which must ensure system usability by residents who have disabilities. Discussion: While program access obligations may arise out of an expressed individual need for accommodation at a specific location, required transit system usability is dependent on having accessible bus stops where people want to go. In urban areas, jurisdictions should not wait for a resident request to improve a bus stop. In rural and suburban areas, a prompt response to the request of a passenger with a disability for accommodation may be sufficient. Residents who are not able to use a public transit system because of bus stop inaccessibility may be eligible for paratransit, but it is often more cost effective to improve the accessibility of bus stops instead. The Title II regulation requires structural improvements for program access to conform to alterations standards.

14. Question: Sidewalks will be redesigned and replaced as part of a Main Street improvement program. The existing sidewalk has a cross slope of 5% (1:20). Reducing that cross slope could result in steps at the entrances to abutting businesses. May the steep cross-slope be retained?

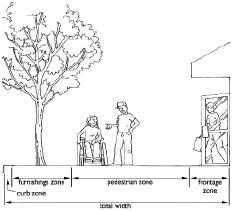

Answer: No. While it is usual to coordinate sidewalk improvements with adjacent property owners, a jurisdiction's first responsibility is to the accessibility of its sidewalks. If a comprehensive project is undertaken to improve sidewalks, the municipality must take the steps necessary to provide usable new sidewalks. It is likely that both usable sidewalks and accessible entrances can be obtained through careful engineering. If existing conditions are extreme, a complex solution that makes use of both public (including roadway) and private space may be required. Discussion: There are many ways of maintaining access without exceeding cross slope limits. Narrow sidewalks may be divided lengthwise into conforming and nonconforming widths, with the non-conforming sections serving as entrance ramps; the entire sidewalk may be raised, with steps at the curb if there is parking; or extra width may be borrowed from a roadway or parking lane. Remember that the cross slope requirement applies only to the Pedestrian Access Route. If there is sufficient sidewalk width, steeper cross slopes can be accommodated in the frontage or furnishing zones to match existing building entrances. Community development block grant money may be available to assist adjacent property owners with building ramps on private property.

PROWAAC Subcommittee members developing these recommendations suggested several new FAQs, developed from their project experiences, to expand the breadth of discussion on alterations. Although not part of the Access Board preamble to the draft PROWAG, they may provide useful guidance:

15. Question: State and local governments are covered by Title II of the ADA, but what about Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act? If a specific project isn't using Federal funds, do the FHWA 504 regulations and associated policies affect the project?

Answer: Yes. As a result of the Civil Rights Restoration Act (CRRA) of 1987, if state or local government public works or highway departments receive any Federal money from any source, not just highway funds, including pass-through funds from the state, the entire program of that local agency is covered. This includes projects undertaken by that agency that do not themselves involve Federal funds. For a full discussion of the impact go to: http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/legsregs/directives/notices/n4720-6.htm.

16. Question: We're re-paving a street. We will be adding/improving curb ramps where needed, but are we required to add accessible on-street parking spaces as part of this project? The parking lane will be re-striped after resurfacing is complete.

Answer: Re-striping on-street parallel parking spaces does not offer any accessibility opportunity (there is no guidance on striping accessibility). However, where perpendicular or angled parking has been provided on a street, it may be feasible after a resurfacing to re-stripe to provide an access aisle for an accessible space (or two) if your jurisdiction doesn't provide sufficient accessible on-street parking (use the new construction scoping to determine the desirable number overall) or if the adjacent land use makes accessible parking particularly desirable in that location. Discussion: The preamble to the DOJ Title II regulation cites adding accessible parking as a program access obligation. Adding accessible parking signs, meters, and curb ramps and relocating curbside barriers, if needed, may be undertaken as program access improvements separately from the resurfacing project, but the striping of an accessible space will give these related needs a higher priority.

Case Study—Steep Terrain at Corner

- Before and after photos show a new segment of sidewalk, with a 2% cross slope and curbs for drainage/erosion control, built to facilitate use of a newly installed curb ramp.

- A level landing on the curbed sidewalk connects to the curb ramp.

- The curb ramp is placed at the flattest portion of the street gutter grade along the radius to minimize warp in the curb ramp to the street.

- Still needed: detectable warnings at street edge.

|

| |

| Case Study—Ponding at a Combined Curb Ramp

- The existing surface drainage conditions were not considered fully when the combination curb ramp shown was selected for this location and ponding resulted.

|

| Case Study—Returned Curb Aids Wayfinding

- This photograph shows a new downtown traffic calming project in Vancouver, WA

- Returned curbs against the landscaped setback provide good orientation cues to crossing pedestrians

- Flares have been minimized in order to make preferred incline/directional ramps possible at this small curb radius

|

| |

| Case Study—Steep Terrain at Corner

- This new combination (parallel and perpendicular) ramp is installed in an existing sidewalk network as a consequence of resurfacing alterations. It is located at the apex of the corner to insure that pedestrians do not enter the crossing in an active traffic lane.

- Roadway surface and gutter have been raised and blended to meet the new parallel ramp, making this a good example of a combination ramp.

- Where true level landings cannot be provided in alterations, it is particularly important to limit sidewalk cross slope to 2%.

Note: DWS needed. |

| |

| |

| Case Study—Adding Pedestrian Signals

- Stub poles are used at these new curb ramps to properly locate the pedbutton near the departure curb.

- For maximum signal discrimination, each crossing direction should have a separately-mounted device; MUTCD standards require a 10-foot minimum between APS.

- While not specified in ADA or 504 Standards, greater accessibility for those with low vision would be provided if the new signal posts were darker and contrasted with the light sidewalk paving.

|

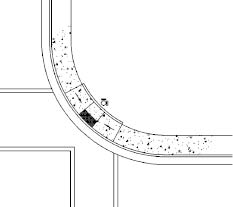

| |

| Case Study—Combination Curb Ramp

- Existing surface drainage patterns along this corner suggested the likelihood of flooding at the central landing of a parallel ramp so a new combination curb ramp design was specified.

- This is a good approach in limited right-of-way. The short perpendicular curb ramp raises the central landing a few inches above the gutter flow line so it is not flooded.

- The design allows for a level bypass space at the top of the flared side ramp while accommodating the limited width of the existing sidewalk.

- Still needed: detectable warnings at toe.

|

| |

Case Study—Midblock Crossing Criteria

- This APS provides audible and vibrotactile notice of the crossing phase at a midblock crossing where there is no parallel traffic surge to provide a cue. Its locator tone also identifies it as an actuated crossing.

- The pedbutton is installed as close to the departure curb as feasible and is operable from the level landing.

- The pedbutton and tactile arrow are oriented parallel to the crosswalk.

|

| |

| |

CHAPTER 3: DESIGN PROCESS

by Andrew Davis, PE, City of Akron, OH; Jerry Markesino, PE, Otak, Inc.; Jim McDonnell, PE, AASHTO; Bob Sexton, PE, HR Gray (Columbus, OH); Bill Hecker, AIA (Birmingham, AL), Ken Stewart, Council on Citizens with Low Vision, International

The design process for making accessibility improvements in alteration projects is not any different from the design process for traditional street modification projects. Incorporating accessible pedestrian elements in the public right-of-way requires the same reference to standards, technical guidance, and product information that designers follow in every roadway design project. The design and placement of curb ramps into an existing developed streetscape is governed by many of the same considerations as roadway design: controlling horizontal and vertical geometries, surface conditions, and access to intersections, all at the scale of the pedestrian rather than the vehicle.

In an alteration, a balance needs to be struck between pedestrian and vehicle users vying for travel space (and time) within a limited right-of-way already constrained by existing development. A good understanding of the rationale behind accessibility standards will help the designer integrate usability for pedestrians who have disabilities into agency decision making.

Resource: FHWA's ‘Designing Sidewalks and Trails for Access, Part 2' at:

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/sidewalk2/index.htm

| |

|

| |

This urban arterial passes through a neighborhood that is undergoing rapid revitalization, with many projects under construction temporarily occupying existing sidewalk space. In this example, the contractor has provided a temporary pedestrian route in the curb lane of the roadway, separating it with Jersey barriers and installing a temporary concrete ramp to the street level walkway. Still needed: detectable warnings at the cross street.

|

Gathering Information

A planned alteration project may arise from a long-planned Capital Improvements Program or be a more immediate response to local conditions or community advocacy. When such construction is undertaken, the new work must incorporate accessibility features. Jurisdictions may have additional obligations for existing facilities under the Title II and 504 regulations (see Chapter 2, Alterations).

Therefore, before developing the scope of work for a planned new project, the design team should contact the jurisdiction or agency ADA/504 Coordinator to identify accessibility improvements that may be needed within or near proposed project boundaries, such as:

- curb ramp transition plans and schedules;

- requested individual accommodations, including APS, parking, curb ramps, and sidewalk repairs; and

- bus stop/transit accessibility improvements.

Often, such improvements can be included in a pending project at a more modest cost than undertaking them independently. Evaluate existing conditions near the project site to determine if key accessibility features or needed maintenance could be provided more economically by slightly expanding the project scope of work. Some agencies have developed ‘spot improvement' programs that use resident requests as input to project scoping. Coordination with transit agencies, which have their own ADA obligations for new construction, alterations, and existing facilities and programs, will indicate whether bus stop locations and shelter space and access requirements would best be addressed within a planned project scope. By gathering this information during preliminary project planning, the engineer can avoid potentially costly oversights and under-designs.

Resources: FHWA's ‘Metropolitan Planning' at:

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/hep/metropol.htm

FTA's civil rights/accessibility page at:

http://www.fta.dot.gov/civilrights/civil_rights_2360.html

Transition Plan, City of Nashville, TN at:

http://www.nashville.gov/gsa/ADA/doj_2047143_final_textonly.htm (see Section VIII: Compliance Strategies for Public Right-of-Way)

State of Hawaii Title II Self Evaluation and Transition Plan at:

http://www.state.hi.us/dlnr/dsp-dp/dsp/rules/draft-transition-plan-self-evaluation.pdf

A newly-funded (2006) National Cooperative Highway Research Project developing guidance for highway agencies on preparing transition plans and meeting program access expectations at:

http://www.trb.org/TRBNet/ProjectDisplay.asp?ProjectID=1247

Planning the Scope of Work

Defining the scope of a planned alteration project establishes the physical and contractual parameters of the work. If right-of-way is to be acquired for a project, it is important to purchase enough to accomplish all project objectives; if an existing right-of-way is to be reapportioned, the scope of work will fix the balance between motor vehicle, cycling, and pedestrian uses. Under-scoping a project may leave or create barriers that will have to be corrected; an oversight that renders a significant part of a planned project inaccessible can entail costly remediation.