Notable Changes in Thermal Activity at Norris Geyser Basin Provide Opportunity to Study Hydrothermal System

Norris Geyser Basin of Yellowstone National Park has long been recognized as having the highest temperature hydrothermal reservoir and is the most changeable of Yellowstone's famous hydrothermal basins. In July 2003, Norris lived up to its hot, unstable reputation as scientists and visitors witnessed changes in many geysers and increased ground temperatures in the southwestern part of the geyser basin. The Yellowstone Volcano Observatory (YVO) seized the opportunity to learn about the activity by installing a temporary monitoring network of seismographs, Global Positioning System (GPS) receivers, and temperature data loggers at Norris. In the coming months, scientists will be poring over the mounds of digitally-acquired data for possible clues to the renewed heating at Norris.

What happened in 2003 at Norris?

First, Steamboat Geyser erupted twice in the Spring of 2003 on 26 March and 27 April, and then again on October 22. Steamboat erupted twice in 2002 and once in 2000 following a nine-year hiatus.

On 10 March 2003, a new thermal feature was reported west of Nymph Lake, located about 3.5 km northwest of the Norris Museum. A linear series of vigorous fumaroles about 75 m long had formed in a forested area located about 200 m from the lake's west shoreline on the side of a hill. Fine particles of rock and mineral fragments ejected from the fumaroles coated nearby vegetation. Fumarole temperatures were as high as 92°C (198°F), the boiling temperature of water at that elevation. After two months, somewhat reduced steam emission was accompanied by discharge of approximately 11 to 38 liters (3 to 10 gallons) per minute of near-neutral thermal water. Trees within 4 m of the lineament had died and were being slowly combusted.

Then, beginning July 11, Yellowstone National Park staff began noticing several changes in the Back Basin at Norris. (See the Yellowstone National Park interactive map of the Norris Geyser Basin for geyser locations.)

Porkchop Geyser, which sprang to life from a small hot spring in 1971, erupted on July 16, 2003 for the first time in many years. The temperature of waters in Porkchop's vent increased continuously from 67°C (152°F) in early April to 88°C (190°F) in early July. Also, water drained away or was boiled to dryness at several active geysers, resulting in hissing steam vents (for example, Pearl Geyser). Still other geysers have erupted more frequently and regularly, while some thermal features that usually release hot water and steam now send steam jetting into the air.

A mud pot also formed along the Back Basin Trail and increased ground temperatures were noted over an 500 x 300 m area. Park staff noted temperatures up to 94°C (200°F) at 1 cm beneath the ground surface in areas that were previously cool. Some of these areas are immediately around the Back Basin Trail. Vegetation in the area immediately died and began to break down due to the high temperatures. On July 23, the park superintendent closed access to the Back Basin, for public safety (other parts of Norris remain open to the public) and the area remains closed.

There is no evidence that magma beneath the enormous Yellowstone caldera is directly involved in the recent changes at Norris or Nymph Lake. Though magma as shallow as 3-6 miles beneath Norris does provide the heat for the geothermal system, the current activity is very unlikely to reflect magma ascent or increased likelihood of volcanism at Yellowstone Park. If magma were to rise to shallow levels beneath the ground it would be accompanied by intense swarms of local earthquakes and extensive displacement (deformation) of the ground surface around Norris. Thus far, caldera-wide seismicity and ground deformation have remained at typical background levels beneath Yellowstone and Norris.

View to south toward thermal feature that appeared 11 July, 2003. This feature is approximately 5 meters to the east of the "Son of Green Dragon" (informal name) thermal feature.

Thermal feature also shown at left is approximately 5 meters to the east of "Son of Green Dragon Spring". Note spattering of mud onto foot trail.

2003 Monitoring Experiment at Norris

To investigate the increased thermal activity, YVO launched a temporary monitoring experiment in August. Besides the University of Utah, U.S. Geological Survey, and Yellowstone National Park, the Norris monitoring experiment is supported by two research organizations-the Integrated Research Institutes in Seismology (IRIS) and University NAVSTAR Consortium (UNAVCO).

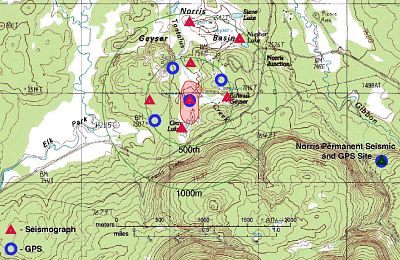

The Norris temporary network was directed by the University of Utah with personnel from the NPS and USGS as well as the UNAVCO assisting. It consists of a network of 7 seismic stations for recording earthquakes. The instruments, called broadband seismometers, record a wide range of vibrations typical of hydrothermal and volcanic systems. These seismometers are especially sensitive to the long-wavelength ground vibrations that occur as water and gas move through underground cracks. Five high-precision Global Positioning System (GPS) receivers also were installed at Norris in order to track vertical and horizontal movement of the ground in response to underground pulses of groundwater and steam and, in case one occurs, a hydrothermal explosion. (Information about the Norris GPS experiment and related technology can be found on the UNAVCO Web site). The seismic component of the experiment was supported by the Integrated Research Institutes in Seismology (IRIS) that provided the special broadband portable seismographs. This array is designed for rapid mobilization of seismic recording from the Rapid Array Mobilization Program (RAMP) designed for response to unanticipated earthquakes and volcanoes. Data from the seismographs and GPS receivers were digitally stored on site, and the instruments and the data were retrieved before the onset of winter.

Scientists set up the "Crater" broadband seismic station on the west side of the Norris Geyser Basin. These instruments can detect long-wavelength movements of the ground, as occurs when pulses of fluid and gas move underground.

The "Porkchop" GPS station, located in the southwestern part of Norris, can detect mm-scale movements of the ground surface.

YVO deployed an array of seismometers and GPS receivers to detect small earthquakes and non-seismic ground movements at Norris. The instruments are spread out at ~600 m intervals around the primary area of increased thermal activity in the Back Basin of Norris.

Thermometers were also placed in hot springs and downstream from geysers and other thermal features to continuously measure temperature fluctuations that may occur. The instruments and data loggers will be left on site during the winter.

The Norris experiment is intended to document activity within the shallow hydrothermal system that may be causing changes at the surface of the Back Basin. Scientists hope to record earthquake signals and surface movements that accompany increased boiling and fluid movement in the shallow subsurface beneath Norris. Another goal of the experiment is to document activity that might occur before a hydrothermal explosion in the Norris area. Such explosions result when hot hydrothermal waters are rapidly converted to steam (boiled), which can rupture and send rocks shooting into the air in a jet of steam and hot water.

Hydrothermal explosions are a real concern for public safety. Explosions are known to have occurred in the past at Norris and other areas of Yellowstone. For example, Porkchop Geyser exploded on September 5, 1989. Rocks surrounding the old geyser were upended by the force of the explosion, and some rocks were thrown more than 66 m (216 feet) from the geyser. Luckily, people in the area were not injured by the flying debris and scalding water. Scientists have never recorded the precursors to such an explosion. If a hydrothermal explosion does occur, perhaps the Norris experiment will help scientists provide warning of possible future events (no such explosion has occurred thus far, however).

Possible relations to the Norris annual disturbance?

The 2003 increased thermal activity in the Back Basin is similar to a long-recognized seasonal phenomenon at Norris where thermal features show signs of increased boiling, added turbidity (cloudiness) and changes in chemical composition. These widespread changes are most common in August and September, but can occur at any time of year. Scientists have coined these seasonal hydrothermal changes at Norris as the "Norris annual disturbance" (see report by White and others, 1988, and Fournier et al., 2002). The changes in 2003 are clearly more intense compared with many of those earlier disturbances, but they are not unprecedented (Bryan, 1989).

Workers have generally concluded that the leading contributor to the disturbance is variation in the pressure within the hydrothermal system. Increased boiling of Norris' thermal waters and higher ground temperatures may be related to the seasonal lowering of the cold, shallow groundwater table. Toward the end of the summer months, the elevation of the cold groundwater table lowers sufficiently such that there is a decrease in pressure within the hydrothermal system. The pressure decrease lowers the boiling-point of the hot rising fluids, sometimes causing increased boiling and sudden flashing to steam, thereby leading to dramatic changes and dramatic changes in hydrothermal activity.

Are this year's events simply a "bad case of the annual disturbance?" Or could changes at Norris be related to regional tectonic strain or even input from the deeper magmatic system (such as increased heat or gas flow)? YVO scientists and collaborators hope to soon learn the answers to these questions.

Stay tuned

The 2003 Norris experiment was perhaps the best opportunity yet to quantitatively document and better understand this hydrothermal disturbance and its possible causes. This winter, scientists will be poring over the mounds of data collected by the Norris experiment for possible clues to the increased thermal activity in 2003 at Norris.

View to the southeast through the area affected by this summer's increased thermal output at Norris' Back Basin. The foreground shows steaming areas where boiling water and steam have approached the surface, resulting in increased ground temperatures.

References

Bryan, T. Scott, Norris Geyser Basin and Fall Disturbance August, 1974 Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, GOSA (Geyser Observation and Study Association)Transactions, v. 1, pp. 203-205, 1989.

Fournier, R. O., Weltman, U., Counce, D., White, L. D., and Janik, C. J., 2002, Results Of Weekly Chemical And Isotopic Monitoring Of Selected Springs In Norris Geyser Basin, Yellowstone National Park During June-September, 1995: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 02-344, 50 p.

White, D.E., Hutchinson, R.A. and Keith, T.E.C., The geology and remarkable thermal activity of Norris Geyser Basin, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, U. S. Geological Survey Professional Paper, Report: P 1456, 84 pp., 1988.