U. S. Coast Guard

A Historical Overview

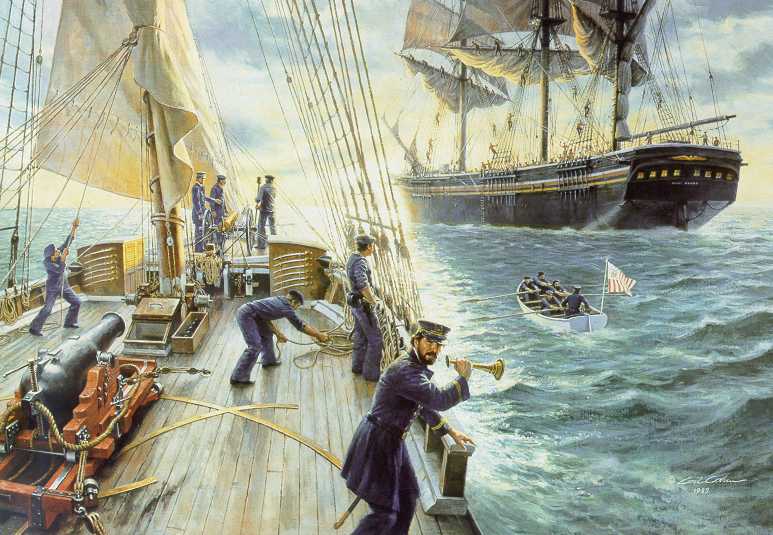

A boarding party from the Revenue Cutter Morris prepares to board the passenger vessel Benjamin Adams on 16 July 1861 about 200 miles east of New York. The Benjamin Adams was bound for New York from Liverpool and carried 650 Scottish and Irish immigrants. The Revenue Cutter Service was originally established to enforce U.S. tariff laws at sea and inspected incoming merchant vessels for compliance with those laws, as is illustrated here.

The United States Coast Guard is this nation's oldest and its premier maritime agency. The history of the Service is very complicated because it is the amalgamation of five Federal agencies. These agencies, the Revenue Cutter Service, the Lighthouse Service, the Steamboat Inspection Service, the Bureau of Navigation, and the Lifesaving Service, were originally independent, but had overlapping authorities and were shuffled around the government. They sometimes received new names, and they were all finally united under the umbrella of the Coast Guard. The multiple missions and responsibilities of the modern Service are directly tied to this diverse heritage and the magnificent achievements of all of these agencies.

Aids

to Navigation

Aids

to Navigation

(Left: an early engraving of the Boston Lighthouse.) One of the first acts of the young federal government was to provide for aids to navigation. On 7 August 1789, the First Congress federalized the existing lighthouses built by the colonies and appropriated funds for lighthouses, beacons, and buoys. Lighthouses generally reflect the existing technology of the time they were built. Each is also unique because their specific sites required special considerations. The earliest Colonial and Federal lighthouses were built of stone and had walls up to seven feet thick. Later advances allowed even taller structures made of brick. Screw-pile structures, reinforced concrete towers, steel towers, and caisson structures all added to the rich and unique architecture.

There have been more than 1,000 lighthouses built and

they provided the main guidance to mariners into the main harbors of the

United States.  For the first five decades there existed little bureaucracy, no tenders,

only the lone keepers who kept the lights burning. The administration

of the lighthouses bounced from the Treasury Department to the Commerce

Department and was transferred to the Coast Guard in 1939.

For the first five decades there existed little bureaucracy, no tenders,

only the lone keepers who kept the lights burning. The administration

of the lighthouses bounced from the Treasury Department to the Commerce

Department and was transferred to the Coast Guard in 1939.

(Right: Cape Hatteras Light Station, 1898.)

While many of the lighthouses have changed little

since their completion, the light sources have continually evolved to

provide mariners with better guidance. Some of the earliest optics

were multiple-wicked oil lamps with reflectors to concentrate the light.

The French physicist Augustin Fresnel revolutionized the optics of

lighthouses by inventing a lens with annular rings, reflectors and

reflecting prisms that all surrounded a single lamp. These lenses proved to

be so effective that many are still in use today providing safe roads for

maritime travelers (below, left: a clamshell-type Fresnel lens).

Sound has also been used to guide ships. In colonial times cannons fired on shore warned ships away from land during fog. Improvements to the sound of gunfire followed. A fog bell first went into use in 1852, followed by a mechanical striking bell in 1869, a fog trumpet in 1872, and an air siren in 1887.

The men and women of the Lighthouse Service were among the most dedicated in government service. They frequently performed their duty in extreme hardship. Abbie Burgess served 38 years in lighthouses. Stationed at the Matinicus Rock and White Head Light Stations in Maine, she dutifully served while simultaneously caring for her family. Keepers were also cited many times for saving lives in shipwreck disasters.

Ida

Lewis (right) saved 18 lives during her 39

years at the Lime Rock Lighthouse and Marcus Hanna the keeper of the Cape

Elizabeth Light is probably the only man in history to have won both the

Medal of Honor and the Gold Lifesaving Medal. Other acts of the

service of keepers are inspiring. Indians attacked the Cape Florida

Lighthouse and set it on fire. The keeper escaped with his life only

after throwing a keg of gunpowder down the burning tower. Other

keepers died on duty, being swept away in storms. The 1906 hurricane

destroyed 23 lights along the Gulf Coast killing the keepers at Horn Island

and Sand Island. An earthquake caused a tsunami in Alaska that killed

the crew of the Scotch Cap Lighthouse (below,

left) in 1946.

Ida

Lewis (right) saved 18 lives during her 39

years at the Lime Rock Lighthouse and Marcus Hanna the keeper of the Cape

Elizabeth Light is probably the only man in history to have won both the

Medal of Honor and the Gold Lifesaving Medal. Other acts of the

service of keepers are inspiring. Indians attacked the Cape Florida

Lighthouse and set it on fire. The keeper escaped with his life only

after throwing a keg of gunpowder down the burning tower. Other

keepers died on duty, being swept away in storms. The 1906 hurricane

destroyed 23 lights along the Gulf Coast killing the keepers at Horn Island

and Sand Island. An earthquake caused a tsunami in Alaska that killed

the crew of the Scotch Cap Lighthouse (below,

left) in 1946.

With the emergence of new technologies, like the Global Positioning System (GPS), in the latter part of the 20th century, lighthouses became obsolete and many light stations were decommissioned and transferred to other agencies or private individuals. As a result there is only one Coast Guard-manned light station remaining in the United States, Boston Harbor.

Though lighthouses are being decommissioned and transferred, the Coast Guard still must tend to other short-range aids to navigation like buoys and markers. As a result, the service began replacing its aged 180-foot buoy tender fleet with the new 175-foot "Keeper"-class (coastal) tenders and 225-foot Juniper-class (seagoing) tenders. The lead vessel in this class was Ida Lewis which was delivered to the Coast Guard on 1 November 1996. These new cutters should ably tend aids to navigation and meet other USCG mission requirements well into the 21st century.

Lightships

(Left:

LV-91, circa 1908.)

(Left:

LV-91, circa 1908.)

Lightships served to guide mariners where there was a need for a light but in a spot where lighthouses could not be placed. There have been over 120 lightship stations along the coast of the United States. The Lighthouse Service placed the first lightship in Chesapeake Bay in 1820. Hundreds of lightships have served along the coasts and usually in extremely exposed anchorages. The vessels carried virtually the same aids to navigation as lighthouses and lasted until 1983 when the Nantucket Lightship was replaced by a Large Navigational Buoy [LNB].

Both storms and ships have taken their toll on

lightships. Hurricanes have sunk and blown many lightships from their

stations, while vessels passing through busy sealanes have collided with and

sunk these floating aids.  One

of the deadliest collisions occurred on 16 May 1934. The 45,000 ton Olympic,

sister of the ill-fated Titanic, struck and sank the Nantucket Shoals

Lightship, L.V.-117.

One

of the deadliest collisions occurred on 16 May 1934. The 45,000 ton Olympic,

sister of the ill-fated Titanic, struck and sank the Nantucket Shoals

Lightship, L.V.-117.

(right) The

liner approached the port of New York in fog and struck and drove the

lightship to the bottom with the loss of seven of her eleven crewmen.

Law Enforcement

Throughout its history the Coast Guard's law enforcement responsibilities have primarily been threefold. First, is to ensure that the tariffs are not avoided. Second, to protect shipping from pirates and any other unlawful interdiction. Third, to intercept material and human contraband.

(Right:

Revenue Captain William Cooke seizes contraband gold landed from a French

privateer, 1793.)

(Right:

Revenue Captain William Cooke seizes contraband gold landed from a French

privateer, 1793.)

Today tariffs hardly seem controversial. But for the first Congress under the Constitution (1789), the imposition of these taxes was a bold act since such taxes had been a primary catalyst for the War of Independence. The young government's need for money was urgent. Trade revenue had to be the lifeblood of the treasury if the new nation was to survive. During colonial days and the War of Independence, smuggling had been a patriotic duty of maritime America. Seamen were admired who circumvented King George's trade laws, and later outran his fleet during the war. In 1789, a new respect for tariffs was needed.

Congress, guided by Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, created a fleet of ten cutters whose responsibilities would be enforcement of the tariff laws. The spirit of the maritime service was captured in Hamilton's insistence upon thrift and responsibility to the public. Hamilton's creation collected money and did not spend it. Seven of the ten cutters were built for the allotted $1,000 each. Two New England cutters exceeded the amount. Due to the severity of the winters, these vessels had to be larger than their southern sisters, Hamilton appreciated the unique problem, but insisted that the boats "be confined to the smallest dimensions...consistent with safety on ... [the Massachusetts] coast however eligible a larger one might be." The third cutter to exceed appropriations was the cutter built for Philadelphia. Costs exceeded the $1,000 figure by $500. Where the extra money came from is unclear, but it didn't come from Secretary Hamilton or the public treasury. The port revenue collector and the citizens of Philadelphia probably paid for the cost overrun. During the cutters' first ten years of service, the imports and exports of the nation rose from $52 million to $205 million. Along with financial responsibility, Hamilton demanded that the officers be servants of the people. "They [the officers] will always keep in mind that their Countrymen are Freemen & as such are impatient of everything that bears that least mark of a domineering Spirit."

The Revenue Cutter McLane enforcing federal tariff laws in Charleston Harbor during the Nullification Crisis of 1832-1833.

National tariffs did not go unchallenged. In 1832, South Carolina tried to nullify these laws. President Andrew Jackson ordered five cutters to Charleston Harbor "to take possession of any vessels arriving from a foreign port, and defend her against any attempts to dispossess the Customs Officers of her custody." He added, "if a single drop of blood shall be shed there in opposition to the laws of the United States, I will hang the first man I can lay my hands on, upon the first tree I can reach."

Protecting commerce also meant suppressing piracy, still a trade practiced well into the 19th Century. In 1819 the cutters Alabama and Louisiana engaged and captured Bravo, commanded by Jean LaFarge, a lieutenant of the notorious Jean Lafitte of New Orleans. These same two cutters destroyed the pirate stronghold of Patterson's Town on Breton Island. In 1822, Louisiana, cooperating with the Royal Navy and US Navy, swept the Caribbean, capturing five pirate vessels.

Intercepting contraband has been the Coast Guard's most controversial commerce protection responsibility. Slavery was the tumultuous social issue of the first half of the 19th century. In 1794 cutters were charged with preventing the introduction of new slaves from Africa. By the Civil War, cutters captured numerous slavers and freed almost 500 slaves. President Thomas Jefferson declared an unpopular embargo of imports in 1808 and cutters closed all the nation's ports.

The first recorded narcotics seizure by a cutter occurred on 31 August 1890 when the USRC Wolcott, stationed in the Straits of Juan de Fuca, boarded and discovered a quantity of undeclared opium on the U.S. flagged steamer George E. Starr. The cutter seized both the vessel and the opium for violations of Customs laws.

Prohibition in the 1920s made the United States a "dry" nation; Coast Guard cutters conducted the unpopular "Rum War at Sea." During the early days of Prohibition, the Coast Guard was seriously handicapped by the lack of vessels, particularly fast ones. By 1924, "Rum Rows" not only graced New York's doorsteps, but fleets of rum-running craft from broken-down fisherman to freighters of considerable tonnage, hovered off the coasts of the United States, more or less, permanently.

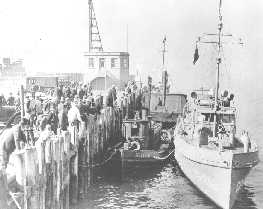

(Left:

a Coast Guard patrol boat returns to port with vessels seized for violation

of the Volstead Act, circa 1927.)

(Left:

a Coast Guard patrol boat returns to port with vessels seized for violation

of the Volstead Act, circa 1927.)

On 20 March 1929 I'm Alone, of Canadian registry, was anchored off the coast of New Orleans with 2,800 cases of liquor on board. When the cutter Wolcott came into sight, I'm Alone moved seaward. Wolcott asked the Canadian to heave to so that she could be boarded and examined. I'm Alone refused. Wolcott fired several shells from her single three-pounder across the Canadian's bow. Then the Wolcott's gun jammed and she called for assistance. The cutters Dexter and Dallas responded. That evening I'm Alone hove to. An unarmed officer from Wolcott was allowed to come on board, but the Canadian skipper refused to permit any search. The officer returned to his cutter and the pursuit continued.

Next day, Dexter and Dallas joined in the pursuit. Dexter ordered the Canadian to "Heave to or I shall fire at you." The skipper of I'm Alone refused on the grounds that he was then on the high seas 14 or 15 miles from land or well beyond the legal limit of 12 miles. I'm Alone was sunk at Latitude 25 degrees, 45 minutes West by gunfire from the cutters, interrupted by repeated demands to "heave to." All but one member of the crew was rescued. The commander of the Wolcott insisted that I'm Alone was but 10.8 miles from the coast by his calculations. The Canadian government sent a strongly worded protest to Washington and the controversy dragged through years of legal and diplomatic bickering, finally being settled by arbitration. Such unpopular actions resulted in many instances of negative press, leading one editor to write "Who's Watching the Coast Guard While the Coast Guard's Watching the Coast?"

(Right:

the Coast Guard Destroyer Tucker, flagship of the Coast Guard's

New London Destroyer Force. The Navy transferred a number of its

"mothballed" destroyers to the Coast Guard during the enforcement

of Prohibition. Tucker was originally commissioned by the Navy

in 1916, she was transferred to the Coast Guard in 1926 and served until

1933.)

(Right:

the Coast Guard Destroyer Tucker, flagship of the Coast Guard's

New London Destroyer Force. The Navy transferred a number of its

"mothballed" destroyers to the Coast Guard during the enforcement

of Prohibition. Tucker was originally commissioned by the Navy

in 1916, she was transferred to the Coast Guard in 1926 and served until

1933.)

In another celebrated case, the CG-249 overtook a motorboat off the Florida coast. The two men on board had 20 cases of whisky. A young Coast Guardsman and a member of the U.S. Secret Service were killed in a melee that ensued. One of the two rumrunners turned state's evidence and was sentenced to a year and a day in prison. The other was hanged at the Coast Guard Base at Fort Lauderdale, Florida after the Supreme Court refused to review the case.

Having taken on board no less than half a million dollars worth of liquor at St. Pierre Island, Holewood ran down the coast to a point off New York where her crew proceeded to camouflage her to look like a well known American coaster, Texas Ranger. Disguised, she steamed up the Narrows and was reported as the latter vessel by marine observers. A careful Coast Guard officer, however, detected the fraud. He consulted a shipping news bulletin that reported the Texas Ranger was in the Gulf of Mexico that day. The pseudo-Texas Ranger was overtaken near Haverstraw, her captain and crew attempting to escape in a ship's boat. A search revealed the $500,000 of choice liquors, the Coast Guard's largest single catch.

When the profit was taken from liquor running by the repeal of prohibition (5 December 1933), smuggling declined, but did not cease. Several small boats in the Gulf of Mexico continued to run guns to Central American countries and return with narcotics before World War II. It was estimated that 80 to 90 percent of the narcotics smuggled into the United States by 1937 were brought in from Asia. The dropping of narcotics in waterproof containers by incoming vessels became so widespread that Coast Guard patrol boats were assigned to meet these ships far out at sea and trail them right in to their docks.

Intercepting contraband had been the Coast Guard's prime mission prior to World War II. This responsibility had been magnified by Prohibition, (1920-1933), and later in that decade by the prelude of World War II. Following the war, the Coast Guard's prime responsibility shifted largely to safety at sea and aiding navigation.

In the early 1960s, law enforcement once again assumed

increased significance. In 1959, Fidel Castro took power in Cuba and

within two years, the Coast Guard established patrols to aid refugees and to

enforce neutrality, interdicting the transportation of men and arms.

This responsibility peaked in 1965 due to increased restrictions on

immigration from Cuba and then abated until the Mariel Boatlift of 1980.

Boats with Cuban migrants began departing Mariel, Cuba, in April, 1980, (right) after Castro declared the port of Mariel "open." Hundreds of small craft departed Miami and sailed to Mariel, where they loaded up with refugees, in most cases more than the craft was designed to carry safely, and then attempted to return to Miami. What followed became the largest Coast Guard operation ever undertaken in peacetime to that date and is a remarkable example of the Coast Guard's ability to respond to a developing crisis quickly.

Coast Guard resources were sent from all over the Atlantic seaboard to reinforce the taxed Seventh District, and President Jimmy Carter called up 900 reservists to active duty in that District. Coast Guard Auxiliarists also contributed to Coast Guard operations by filling in at various bases, sailing their own vessels and flying their own aircraft to augment the active duty personnel. The President also ordered Navy assets to assist as well. By the time the boatlift came to an end, over 125,000 Cubans had made the journey to the United States and of those only 27 perished at sea, a remarkable example of the effectiveness of the men and women in uniform who responded to the crisis with little to no warning beforehand.

During

the early 1970s, an old law enforcement job, drug interception, took on

increasing emphasis that continues today. From 1963 through 1979, the

Coast Guard seized 304 vessels, confiscated over $4 billion in contraband

and made 1,959 arrests. The illegal importation of narcotics continued

to grow in the 1980s and 1990s. In an effort to combat this problem

the Coast Guard expanded its interdiction efforts. On 9 August 1982

the Department of Defense approved the use of Coast Guard law enforcement

detachments on board US Navy vessels during peacetime. The teams

conducted law enforcement boardings from Navy vessels for the first time in

U.S. history. In 1995 a Coast Guard LEDET seized the F/V Nataly I when

the team discovered 24,325 pounds of cocaine hidden on board, making this

the largest U.S. maritime seizure of cocaine to date.

During

the early 1970s, an old law enforcement job, drug interception, took on

increasing emphasis that continues today. From 1963 through 1979, the

Coast Guard seized 304 vessels, confiscated over $4 billion in contraband

and made 1,959 arrests. The illegal importation of narcotics continued

to grow in the 1980s and 1990s. In an effort to combat this problem

the Coast Guard expanded its interdiction efforts. On 9 August 1982

the Department of Defense approved the use of Coast Guard law enforcement

detachments on board US Navy vessels during peacetime. The teams

conducted law enforcement boardings from Navy vessels for the first time in

U.S. history. In 1995 a Coast Guard LEDET seized the F/V Nataly I when

the team discovered 24,325 pounds of cocaine hidden on board, making this

the largest U.S. maritime seizure of cocaine to date.

(Right: Tampa and other cutters seize a "go-fast" boat

loaded with 5,000 lbs of marijuana.)

(Right: Tampa and other cutters seize a "go-fast" boat

loaded with 5,000 lbs of marijuana.)

Some of the more noteworthy drug seizures included the following. On 1 November 1984 the cutter Clover nabbed the 63-foot yacht Arrikis 150 miles southwest of San Diego. The yacht was loaded with 13 tons of marijuana and was the largest marijuana bust to date on the West Coast. A few days later, on 4 November, USCGC Northwind became the first icebreaker to make a seizure of narcotics when she captured the P/C Alexi I off Jamaica while carrying 20 tons of marijuana. On 8 May 1987 Coast Guard units, including the cutter Ocracoke, made the largest seizure of cocaine by the Coast Guard to date, 1.9 tons. The Coast Guard expanded its drug-interdiction effort with largest counter-narcotics operation in Coast Guard history when Operation Frontier Shield commenced on 1 October 1996. On 28 April 2001 a LEDET assigned to the USS Rodney M. Davis, with later assistance from the Active (based in Port Angeles, WA) made the largest cocaine seizure in maritime history when they boarded and seized the Belizean F/V Svesda Maru 1,500 miles south of San Diego. The fishing vessel was carrying 26,931 pounds of cocaine. These are but a few examples of the Coast Guard's continuing effort to combat the flow of illegal drugs into the United States.

Military Readiness

The Coast Guard, through its forefathers, is the oldest continuous seagoing service and has fought in almost every war since the Constitution became the law of the land in 1789. Following the War of Independence (1776-83), the Continental Navy was disbanded and from 1790 until 1794, when Congress authorized the construction of six frigates (of which only three were launched by 1797), the revenue cutters were the only national maritime service. The Acts establishing the Navy also empowered the President to use the revenue cutters to supplement the fleet when needed. Laws later clarified the relationship between the Coast Guard and the Navy.

The

Coast Guard has traditionally performed two roles in wartime. The

first has been to augment the Navy with men and cutters. The second has been

to undertake special missions, for which peacetime experiences have prepared

the Service with unique skills. During the Quasi-War with France

(1798-99), eight cutters operated along our southern coast in the Caribbean

Sea, and among the West Indies Islands. (Right:

the cutter Eagle captures the French privateer Bon Pere in

April, 1799.) Cutters captured 18 prizes

unaided and assisted in the capture of two others. The cutter Pickering

made two cruises to the West Indies and captured 10 prizes, one of which

carried 44 guns and 200 men, three times her own force.

The

Coast Guard has traditionally performed two roles in wartime. The

first has been to augment the Navy with men and cutters. The second has been

to undertake special missions, for which peacetime experiences have prepared

the Service with unique skills. During the Quasi-War with France

(1798-99), eight cutters operated along our southern coast in the Caribbean

Sea, and among the West Indies Islands. (Right:

the cutter Eagle captures the French privateer Bon Pere in

April, 1799.) Cutters captured 18 prizes

unaided and assisted in the capture of two others. The cutter Pickering

made two cruises to the West Indies and captured 10 prizes, one of which

carried 44 guns and 200 men, three times her own force.

Augmenting the Navy with shallow-draft craft evolved out of the War of 1812 into a continuing wartime responsibility. During the opening phases of the war, Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin addressed Congress. He said, "We want small, fast sailing vessels...there are but six vessels belonging to the Navy, under the size of frigates; and that number is inadequate." During the last two centuries, cutters have been used extensively in "brown water" combat. A cutter made the first capture of the war. One of the most hotly contested engagements was between the cutter Surveyor and the British frigate Narcissis. The Surveyor was captured. The British Captain wrote to Captain Samuel Travis on the following day,

"Your gallant and desperate attempt to defend your vessel against more than double your number excited such admiration on the part of your opponents as I have seldom witnessed, and induced me to return you the sword you so ably used in testimony of mine... I am at loss which to admire most, the previous arrangement on board the Surveyor or the determined manner in which her deck was disputed inch by inch."

The

defense of the cutter Eagle (left) against

the attack of the British brig Dispatch and an accompanying sloop, is

one of the most dramatic incidents of the War of 1812. The cutter was

run ashore on Long Island. Her guns were dragged up on a high bluff and from

there the crew of Eagle fought the British ships from 9 o'clock in

the morning until late in the afternoon. When they had exhausted their

shot, they tore up the ship's logbook as wads and fired back the enemy's

shot that lodged against the hill. During the engagement the cutter's

flag was shot away three times and was as often replaced by volunteers from

the crew on the hill. Finally, the British took the beached cutter

with overwhelming numbers.

The

defense of the cutter Eagle (left) against

the attack of the British brig Dispatch and an accompanying sloop, is

one of the most dramatic incidents of the War of 1812. The cutter was

run ashore on Long Island. Her guns were dragged up on a high bluff and from

there the crew of Eagle fought the British ships from 9 o'clock in

the morning until late in the afternoon. When they had exhausted their

shot, they tore up the ship's logbook as wads and fired back the enemy's

shot that lodged against the hill. During the engagement the cutter's

flag was shot away three times and was as often replaced by volunteers from

the crew on the hill. Finally, the British took the beached cutter

with overwhelming numbers.

Revenue cutters fought a tenacious riverine war (1836-39) with the Seminole Indians in Florida. Cutters attacked parties of hostile Indians, broke up their rendezvous, picked up survivors of massacres, carried dispatches, transported troops, blockaded rivers to the passage of Indian forces, and landed riflemen and artillery for the defense of the settlements. These duties covered the whole coast of Florida. At the outbreak of the Mexican War (1846-48), the Navy was once again critically short of small steamers and schooners; cutters filled the void. Here, the shallow-draft revenue steamers assisted in amphibious operations against the Mexicans by towing ashore naval craft packed with Marines and seamen.

Military preparedness has never been limited to declared war. Second Lieutenant James E. Harrison, of the Revenue Cutter Jefferson Davis stationed in Puget Sound, accompanied Company C, 4th US Infantry, commanded by Lieutenant W. A. Slaughter, USA, during the Indian uprising in the state of Washington in 1855. The Service had been assisting the Army throughout the Puget Sound area and Harrison was acting as second in command. On December 3, while in camp, Indians ambushed the company and killed Lt. Slaughter, placing the command of a regular army company on Lt. Harrison. He immediately rallied the company and engaged in a hot firefight to beat off the attackers. Harrison then led his company back to Fort Steilacoom, arriving on 21 December 1855. In 1858, the cutter Harriet Lane was part of a naval squadron sent to blockade Paraguay.

"If

any men attempts to haul down the American flag, shoot him on the

spot." Secretary of the Treasury John A. Dix telegraphed this

message on the evening of January 15, 1861, attempting to retain under

Federal control the cutter Robert McClellan, then lying in the port

of New Orleans. As within the country, the sympathies of the cutter

force were divided between the North and the South. Principal wartime

duties of those cutters serving the Union were patrolling for commerce

raiders and providing fire support of troops ashore; those serving the

Confederacy were used principally as commercial raiders. Cutters were

involved in individual actions. Harriet Lane, under the command

of Captain John Faunce, fired the first naval shots of the Civil War.

On 11 April 1861, she challenged the steamer Nashville with a shot

across its bow (above, left).

In December 1862, the cutter Hercules battled Confederate forces on

the Rappahannock River. The cutter Miami carried President

Abraham Lincoln and his party to Fort Monroe in May 1862, preparatory to the

Peninsular Campaign. Cutter Reliance engaged Confederate forces

on Great Wicomico River in Virginia in 1864. Her commanding officer

was killed in the action. On April21, 1865, cutters were ordered to

search all outbound ships for the assassins of the President.

"If

any men attempts to haul down the American flag, shoot him on the

spot." Secretary of the Treasury John A. Dix telegraphed this

message on the evening of January 15, 1861, attempting to retain under

Federal control the cutter Robert McClellan, then lying in the port

of New Orleans. As within the country, the sympathies of the cutter

force were divided between the North and the South. Principal wartime

duties of those cutters serving the Union were patrolling for commerce

raiders and providing fire support of troops ashore; those serving the

Confederacy were used principally as commercial raiders. Cutters were

involved in individual actions. Harriet Lane, under the command

of Captain John Faunce, fired the first naval shots of the Civil War.

On 11 April 1861, she challenged the steamer Nashville with a shot

across its bow (above, left).

In December 1862, the cutter Hercules battled Confederate forces on

the Rappahannock River. The cutter Miami carried President

Abraham Lincoln and his party to Fort Monroe in May 1862, preparatory to the

Peninsular Campaign. Cutter Reliance engaged Confederate forces

on Great Wicomico River in Virginia in 1864. Her commanding officer

was killed in the action. On April21, 1865, cutters were ordered to

search all outbound ships for the assassins of the President.

In

the Spanish-American War, cutters fought in the Caribbean and Far East.

Eight cutters, carrying 43 guns, were in Admiral William Sampson's fleet and

on the Havana blockade. McCulloch, carrying six guns and manned

by 10 officers and 95 crewmen, was at the battle of Manila Bay and,

subsequently, was employed by Admiral George Dewey, USN, as his dispatch

boat. At the battle of Cardenas, 11 May 1898, the cutter Hudson

(right) sustained the fight against the

gunboats and shore batteries of the enemy side by side with the torpedo boat

USS Winslow. When Ensign Bagley, USN, and half the crew had

been killed and her commanding officer wounded, Hudson rescued the

craft from destruction while under furious fire from the enemy's guns.

In recognition of this act, Congress authorized that a gold medal be

presented to Lieutenant Frank Newcomb, USRCS, a silver medal to each of his

officers, and a bronze medal to each member of his crew.

In

the Spanish-American War, cutters fought in the Caribbean and Far East.

Eight cutters, carrying 43 guns, were in Admiral William Sampson's fleet and

on the Havana blockade. McCulloch, carrying six guns and manned

by 10 officers and 95 crewmen, was at the battle of Manila Bay and,

subsequently, was employed by Admiral George Dewey, USN, as his dispatch

boat. At the battle of Cardenas, 11 May 1898, the cutter Hudson

(right) sustained the fight against the

gunboats and shore batteries of the enemy side by side with the torpedo boat

USS Winslow. When Ensign Bagley, USN, and half the crew had

been killed and her commanding officer wounded, Hudson rescued the

craft from destruction while under furious fire from the enemy's guns.

In recognition of this act, Congress authorized that a gold medal be

presented to Lieutenant Frank Newcomb, USRCS, a silver medal to each of his

officers, and a bronze medal to each member of his crew.

Also during the Spanish-American War, the Navy assigned the coast watching mission to the U.S. Life-Saving Service. As a result, approximately two-thirds of the Navy's coastal observation stations along the coastline of the U.S. were Life-Saving Stations. At no time was the elusive Spanish fleet observed along our coastline, but the 24-hour-a-day job was accomplished by a Coast Guard predecessor.

On the morning of 6 April 1917, a coded dispatch was sent from Washington to every cutter and shore station of the Coast Guard. Within a few hours the entire Coast Guard, officers and enlisted men, vessels and units came under the operational control of the U.S. Navy. In August and September 1917 six Coast Guard cutters, Ossipee, Seneca, Yamacraw, Algonquin, Manning, and Tampa left the United States to join our naval forces in European waters. They constituted Squadron 2 of Division 6 of the Atlantic Fleet's patrol forces based at Gibraltar. Throughout World War I, they escorted hundreds of vessels between Gibraltar and the British Isles, and also performed escort and patrol duty in the Mediterranean.

On the evening of 26 September 1918, Tampa (right)

having acted as ocean escort for a convoy from Gibraltar to the United

Kingdom, proceeded toward the port of Milford Haven, Wales. At 8:45 p.m. a

loud explosion was heard. Tampa failed to arrive at her

destination and a search was made for her by U.S. destroyers and British

patrol craft. A small amount of wreckage identified as belonging to

the cutter and two unidentified bodies in naval uniforms were found.

It was believed that Tampa was sunk by a German submarine.

Every officer and enlisted man on board Tampa perished. There

were 115 in all, 111 of whom were Coast Guard personnel. With the

exception of U.S.S. Cyclops, whose fate has never been ascertained,

this was the largest loss of life incurred by any U.S. naval unit during the

war. The British Admiralty wrote to Rear Admiral William Sims, USN:

On the evening of 26 September 1918, Tampa (right)

having acted as ocean escort for a convoy from Gibraltar to the United

Kingdom, proceeded toward the port of Milford Haven, Wales. At 8:45 p.m. a

loud explosion was heard. Tampa failed to arrive at her

destination and a search was made for her by U.S. destroyers and British

patrol craft. A small amount of wreckage identified as belonging to

the cutter and two unidentified bodies in naval uniforms were found.

It was believed that Tampa was sunk by a German submarine.

Every officer and enlisted man on board Tampa perished. There

were 115 in all, 111 of whom were Coast Guard personnel. With the

exception of U.S.S. Cyclops, whose fate has never been ascertained,

this was the largest loss of life incurred by any U.S. naval unit during the

war. The British Admiralty wrote to Rear Admiral William Sims, USN:

"Their Lordships desire me to express their deep regret at the loss of the U.S.S. Tampa. Her record since she has been employed in European waters as an escort to convoys has been remarkable. She has acted in the capacity of ocean escort to no less than 18 convoys from Gibraltar comprising 350 vessels, with a loss of only 2 ships through enemy action. The commanders of the convoys have recognized the ability with which the Tampa carried out the duties of ocean escort. Appreciation of the good work done by the U.S.S. Tampa may be some consolation to those bereft and Their Lordships would be glad if this could be conveyed to those concerned."

Following the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, the Coast Guard carried out

neutrality patrols as set out by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on 5

September 1939. Port security began on 22 June 1940 when President

Roosevelt invoked the Espionage Act of 1917 which governed the anchorage and

movement of all ships in U.S. waters and protected American ships, harbors

and waters. Shortly afterwards, the Dangerous Cargo Act gave the Coast

Guard jurisdiction over ships carrying high explosives and dangerous

cargoes. In March 1941, the Coast Guard seized 28 Italian, two German

and 35 Danish merchant ships. A few days later, 10 modern Coast Guard

cutters were transferred on Lend-Lease to Great Britain. (Above,

right: Coast Guard beach patrol, circa 1942.)

Following the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, the Coast Guard carried out

neutrality patrols as set out by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on 5

September 1939. Port security began on 22 June 1940 when President

Roosevelt invoked the Espionage Act of 1917 which governed the anchorage and

movement of all ships in U.S. waters and protected American ships, harbors

and waters. Shortly afterwards, the Dangerous Cargo Act gave the Coast

Guard jurisdiction over ships carrying high explosives and dangerous

cargoes. In March 1941, the Coast Guard seized 28 Italian, two German

and 35 Danish merchant ships. A few days later, 10 modern Coast Guard

cutters were transferred on Lend-Lease to Great Britain. (Above,

right: Coast Guard beach patrol, circa 1942.)

On April 9, 1941, Greenland was incorporated into a hemispheric defense system. The Coast Guard was the primary military service responsible for these cold-weather operations, which continued throughout the war. On September 12 the cutter Northland took into "protective custody" the Norwegian trawler Buskoe and captured three German radiomen ashore. This was the United States' first naval capture of World War II.

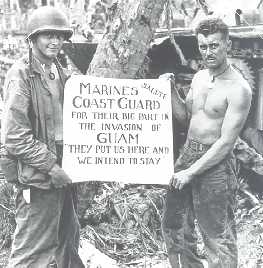

The

Coast Guard was ordered to operate as part of the Navy on 1 November 1941.

During the war, Coast Guard-manned ships sank 11 enemy submarines.

Coast Guard personnel manned amphibious ships and craft, from the largest

troop transports to the smallest attack craft. These landed Army and

Marine forces in every important invasion in North Africa, Italy, France,

and the Pacific. Coast Guard coastal picket vessels patrolled along

the 50- fathom curve, where enemy submarines concentrated early in the war.

While on shore, armed Coast Guardsmen patrolled beaches and docks, on foot,

on horseback, in vehicles, with and without dogs, as a major part of the

nation's anti-sabotage effort.

The

Coast Guard was ordered to operate as part of the Navy on 1 November 1941.

During the war, Coast Guard-manned ships sank 11 enemy submarines.

Coast Guard personnel manned amphibious ships and craft, from the largest

troop transports to the smallest attack craft. These landed Army and

Marine forces in every important invasion in North Africa, Italy, France,

and the Pacific. Coast Guard coastal picket vessels patrolled along

the 50- fathom curve, where enemy submarines concentrated early in the war.

While on shore, armed Coast Guardsmen patrolled beaches and docks, on foot,

on horseback, in vehicles, with and without dogs, as a major part of the

nation's anti-sabotage effort.

Coast Guard craft rescued more than fifteen hundred survivors of torpedo attacks in areas adjacent to the United States. Cutters on escort duty saved another one thousand and over fifteen hundred more were rescued during the Normandy operation. During the war the Coast Guard manned 802 cutters (those over 65 feet in length), 351 naval ships and craft, and 288 Army vessels. Almost two thousand Coast Guardsmen died in the war, a third of those in action. Almost two thousand Coast Guardsmen were decorated, one receiving the Medal of Honor, six the Navy Cross, and one the Distinguished Service Cross. The Coast Guard returned to the Treasury Department on Jan. 1, 1946.

The Service performed primarily a supporting role during the Korean Conflict. Its principal contributions were improving communications and meteorological services plus assuring port security and proper ammunition handling. The Coast Guard also served in Vietnam performing duties uniquely suited to the specialized skills of the Service. In 1965, 26 82-foot Coast Guard cutters were ordered to Vietnam.

These

were used in the "brown water" war, attempting to interdict

Vietcong and North Vietnamese infiltration and logistics. In 1966 the

first ocean-going cutters augmented the Navy and Coast Guard surveillance

forces already in Vietnam. Coast Guardsmen were also detailed to

improve port security, especially in Saigon, to assist with problems

involving the Merchant Marine, and to teach workmen the basics of safe

handling of ammunition and other dangerous cargoes. An in-country

navigation system was created and a Loran network was set up for Southeast

Asia. "Vietnamization" began in February 1969 and was

concluded by December 1971. In all, 56 Coast Guard cutters served in

Vietnam.

These

were used in the "brown water" war, attempting to interdict

Vietcong and North Vietnamese infiltration and logistics. In 1966 the

first ocean-going cutters augmented the Navy and Coast Guard surveillance

forces already in Vietnam. Coast Guardsmen were also detailed to

improve port security, especially in Saigon, to assist with problems

involving the Merchant Marine, and to teach workmen the basics of safe

handling of ammunition and other dangerous cargoes. An in-country

navigation system was created and a Loran network was set up for Southeast

Asia. "Vietnamization" began in February 1969 and was

concluded by December 1971. In all, 56 Coast Guard cutters served in

Vietnam.

With the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait on 1 August 1990, the Coast Guard was again called to perform military duties. On 17 August 1990, at the request of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Secretary of Transportation and the Commandant of the Coast Guard commit Coast Guard law enforcement boarding teams [LEDETs] to Operation Desert Shield. A total of 10 four-person teams served in theatre to support the enforcement of UN sanctions by the Maritime Interdiction Forces. Approximately 60 percent of the 600 boardings carried out by U.S. forces were either led by or supported with the USCG LEDETs. Additionally, a 7-man liaison staff was designated by the Commandant as Operational Commander for the USCG forces deployed in theatre. The first boarding of an Iraqi vessel in the theatre of operations conducted by a USCG LEDET occurred on 30 August 1990.

(Left:

a PSU's Tactical Port Security Boat inspects a fishing vessel in Kuwait.)

President George H. W. Bush, on 22 August

1990, authorized the call up of members of the selected reserve to active

duty in support of Operation Desert Shield. Three port security units

(PSUs), consisting of 550 Coast Guard reservists are ordered to the Persian

Gulf in support of Operation Desert Shield. (This was the first

involuntary overseas mobilization of Coast Guard Reserve PSUs in the Coast

Guard Reserve's 50-year history). A total of 950 Coast Guard

reservists are called to active duty. Other reservist duties included

supervising RRF vessel inspection and loading hazardous military cargoes.

On 15 September 1990 the Secretary of Transportation and the commandant

committed the first-ever deployment of a Coast Guard Reserve port security

unit overseas, Port Security Unit 303. Prior to the launch of

Operation Desert Storm, Coast Guard LEDET personnel on board the USS Nicholas

(FFG-11) assisted when the frigate cleared eleven Iraqi oil platforms and

took 23 prisoners on18 January 1991. On April 21,1991, a Tactical Port

Security Boat (TPSB) of PSU 301, stationed in Al Jubayl, Saudi Arabia, was

the first boat in the newly reopened harbor of Mina Ash Shuwaikh in Kuwait

City. Because of certain security concerns, a determination was made

to send one of the 22-foot Raider boats belonging to PSU 301 and armed with

.50 caliber and M60 machine guns, to lead the procession into the harbor and

provide security for the festivities.

(Left:

a PSU's Tactical Port Security Boat inspects a fishing vessel in Kuwait.)

President George H. W. Bush, on 22 August

1990, authorized the call up of members of the selected reserve to active

duty in support of Operation Desert Shield. Three port security units

(PSUs), consisting of 550 Coast Guard reservists are ordered to the Persian

Gulf in support of Operation Desert Shield. (This was the first

involuntary overseas mobilization of Coast Guard Reserve PSUs in the Coast

Guard Reserve's 50-year history). A total of 950 Coast Guard

reservists are called to active duty. Other reservist duties included

supervising RRF vessel inspection and loading hazardous military cargoes.

On 15 September 1990 the Secretary of Transportation and the commandant

committed the first-ever deployment of a Coast Guard Reserve port security

unit overseas, Port Security Unit 303. Prior to the launch of

Operation Desert Storm, Coast Guard LEDET personnel on board the USS Nicholas

(FFG-11) assisted when the frigate cleared eleven Iraqi oil platforms and

took 23 prisoners on18 January 1991. On April 21,1991, a Tactical Port

Security Boat (TPSB) of PSU 301, stationed in Al Jubayl, Saudi Arabia, was

the first boat in the newly reopened harbor of Mina Ash Shuwaikh in Kuwait

City. Because of certain security concerns, a determination was made

to send one of the 22-foot Raider boats belonging to PSU 301 and armed with

.50 caliber and M60 machine guns, to lead the procession into the harbor and

provide security for the festivities.

On

11 September 2001, terrorists from Osama bin Laden's Al Qaeda network,

hijacked four commercial aircraft, crashing two into the World Trade Center

in New York and one into the Pentagon in Washington, DC (the fourth aircraft

crashed around Shanksville, PA when passengers on board tried to regain

control from the terrorists). USCG units from Activities New York were

among the first military units to respond in order to provide security and

render assistance to those in need.

On

11 September 2001, terrorists from Osama bin Laden's Al Qaeda network,

hijacked four commercial aircraft, crashing two into the World Trade Center

in New York and one into the Pentagon in Washington, DC (the fourth aircraft

crashed around Shanksville, PA when passengers on board tried to regain

control from the terrorists). USCG units from Activities New York were

among the first military units to respond in order to provide security and

render assistance to those in need.

(Right: the Tahoma controls vessel traffic in New York harbor while the World Trade Center complex burns in the background.)

In response to the terrorist threat and to protect our nation's coastline, ports and waterways, six U.S. Navy Cyclone-class patrol coastal warships were assigned to Operation Noble Eagle on 5 November 2001. This was the first time that U.S. Navy ships were employed jointly under Coast Guard command.

(Left:

A Maritime Safety and Security Team patrols a major U.S. port. MSSTs

were established to ensure the safety of US ports.)

(Left:

A Maritime Safety and Security Team patrols a major U.S. port. MSSTs

were established to ensure the safety of US ports.)

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks President George W. Bush proposed the creation of a new Cabinet-level agency, eventually named the Department of Homeland Security. The Coast Guard was foremost among the agencies slated to become a constituent of the new department. On 25 November 2002, President Bush signed HR 5005 creating the Department of Homeland Security. Soon after, Tom Ridge, former governor of Pennsylvania, was confirmed as the department's first Secretary. On 25 February 2003, Transportation Secretary, Norman Mineta transferred leadership of the U.S. Coast Guard to Secretary Ridge, formally recognizing the change in civilian leadership over the Coast Guard and ending the Coast Guard's almost 36 year term as a member of the Department of Transportation.

As a prominent member of the new department, US Coast Guard units deployed

to Southwest Asia in support of the US-led coalition engaged in Operation

Iraqi Freedom early in 2003. (Right: USCGC Wrangell escorts the

British vessel Sir Galahad into Iraqi waters.)

As a prominent member of the new department, US Coast Guard units deployed

to Southwest Asia in support of the US-led coalition engaged in Operation

Iraqi Freedom early in 2003. (Right: USCGC Wrangell escorts the

British vessel Sir Galahad into Iraqi waters.)

Environmental Protection

The Coast Guard has helped to protect he environment for over 180 years. In 1822 he Congress created a timber reserve for the Navy and authorized the President to use whatever forces necessary to prevent the cutting of live-oak on public lands. The shallow-draft revenue cutters were well-suited to this service and were used extensively.

The ecological responsibilities of the Service were

greatly expanded by the purchase of Alaska in 1867. Fur seals were

being hunted into extinction due to the value of their coats. Seal

herds congregated each year to breed on the Pribilof Islands where they were

ruthlessly slaughtered. A quarter-million were killed during the first

four years of American control of the territory. In 1870 Congress

restricted the number that could be killed. Beginning in 1894, small parties

of Revenue Cutter Service personnel were camped on the Pribilof Islands to

prevent raids on the seal rookeries. On 11 May 1908, revenue cutters

were given the authority to enforce all Alaskan game laws.

(Right: the cutter Rush patrolling in the Bering Sea, circa 1895.)

In 1885 the Revenue Cutter Service cooperated with the Bureau of Fisheries in connection with "propagation of food fishes." Twenty years later, cutters enforced the regulations governing the landing, delivery, cure, and sale of sponges in the Gulf of Mexico.

Clean waters have been a concern for many decades. The Refuse Act of 1899 was the first attempt to address the growing problem of pollution and was jointly enforced by the Army Corps of Engineers and the Revenue Cutter Service. Today, the current framework for the Coast Guard's Marine Environmental Protection program is the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1972.

In

1973, the Coast Guard created a National Strike Force to combat oil spills.

There are three teams, a Pacific unit based near San Francisco, a Gulf team

at Mobile, Ala., and an Atlantic Strike Team stationed in Elizabeth City,

N.C. Since the creation of the force, the teams have been deployed worldwide

to hundreds of potential and actual spill sites, bringing with them a vast

array of sophisticated equipment. Their most notable

"battles" were with Metula in the Straits of Magellan

during August 1974, Showa Maru in the Straits of Malacca during

January 1975, Olympic Games in the Delaware River during December

1975, and Argo Merchant (above, left) during December 1976.

In

1973, the Coast Guard created a National Strike Force to combat oil spills.

There are three teams, a Pacific unit based near San Francisco, a Gulf team

at Mobile, Ala., and an Atlantic Strike Team stationed in Elizabeth City,

N.C. Since the creation of the force, the teams have been deployed worldwide

to hundreds of potential and actual spill sites, bringing with them a vast

array of sophisticated equipment. Their most notable

"battles" were with Metula in the Straits of Magellan

during August 1974, Showa Maru in the Straits of Malacca during

January 1975, Olympic Games in the Delaware River during December

1975, and Argo Merchant (above, left) during December 1976.

On

24 March 1989 the supertanker Exxon Valdez ran aground on Bligh Reef

in Alaska's Prince William Sound (right).

At the height of the cleanup CGC Rush, with suitable radar, became a

floating air traffic control tower, directing more than 300 aircraft daily

in and around the spill site. The Exxon Valdez disaster led to

the passage of the Oil Protection Act of 1990. OPA '90, as it became

known, was the single largest law enforcement tasking of the US Coast Guard

since the passage of Prohibition.

On

24 March 1989 the supertanker Exxon Valdez ran aground on Bligh Reef

in Alaska's Prince William Sound (right).

At the height of the cleanup CGC Rush, with suitable radar, became a

floating air traffic control tower, directing more than 300 aircraft daily

in and around the spill site. The Exxon Valdez disaster led to

the passage of the Oil Protection Act of 1990. OPA '90, as it became

known, was the single largest law enforcement tasking of the US Coast Guard

since the passage of Prohibition.

Even

in times of war, the Coast Guard has been engaged in protecting the

environment. On 13 February 1991, in response to the Iraqi firing oil

wells and pumping stations, that caused oil spills in the Persian Gulf, two

HU-25A Falcon jets from Air Station Cape Cod, equipped with Aireye

technology [which precisely locates and records oil as it floats on water],

departed for Saudi Arabia as part of the Inter-agency oil spill assessment

team [USIAT]. They were accompanied by two HC-130 aircraft from Air

Station Clearwater which transported spare parts and deployment packages.

The Falcons mapped over 40,000 square miles in theatre and located

"every drop of oil on the water...The USIAT used the mapping product to

produce a daily updated surface analysis of the location, condition, and

drift projections of the oil." The AVDET was deployed for 84

days, flew 427 flight hours and maintained an aircraft readiness rate of

over 96 percent.

Even

in times of war, the Coast Guard has been engaged in protecting the

environment. On 13 February 1991, in response to the Iraqi firing oil

wells and pumping stations, that caused oil spills in the Persian Gulf, two

HU-25A Falcon jets from Air Station Cape Cod, equipped with Aireye

technology [which precisely locates and records oil as it floats on water],

departed for Saudi Arabia as part of the Inter-agency oil spill assessment

team [USIAT]. They were accompanied by two HC-130 aircraft from Air

Station Clearwater which transported spare parts and deployment packages.

The Falcons mapped over 40,000 square miles in theatre and located

"every drop of oil on the water...The USIAT used the mapping product to

produce a daily updated surface analysis of the location, condition, and

drift projections of the oil." The AVDET was deployed for 84

days, flew 427 flight hours and maintained an aircraft readiness rate of

over 96 percent.

The 200-mile zone created by the Fishery Conservation and Management Act of 1976 quadrupled the offshore fishing area controlled by the United States. The Coast Guard has the responsibility of enforcing this law. The Coast Guard also monitors a number of international agreements, treaties and conventions, including the UN moratorium on High Seas Drift Net Fishing. This indiscriminate fishing method using large-scale drift nets, sometimes more than 25 miles in length, had been banned on the high seas since 1991. As a result of U.S-led efforts, supported by Coast Guard aircraft and cutter patrols, the nations operating these vessels have virtually abandoned this practice.

(Left:

a boarding team inspects the catch of a fishing vessel in the Atlantic.)

(Left:

a boarding team inspects the catch of a fishing vessel in the Atlantic.)

A noteworthy case involving a high seas drift net vessel occurred in July 1997. A Canadian aircraft spotted the vessel Cao Yu 6025 fishing 1,100 miles northwest of Midway Island. After spotting the surveillance aircraft, the vessel's crew attempted to flee. Canadian and U.S. Coast Guard aircraft tracked it, while USCGC Basswood attempted an intercept. After a 1,700-mile chase, Basswood, along with the USCGC Chase, boarded the vessel in the East China Sea. The Cao Yu along with its catch of 120 tons of albacore, swordfish and shark fins, was seized. In June 1998 the cutters Boutwell, Jarvis, Polar Sea, Coast Guard aircraft, along with two Russian fisheries patrol vessels seized a total of four Chinese fishing vessels suspected of high-seas driftnet fishing. This was the largest high-seas driftnet fisheries bust ever for the Coast Guard.

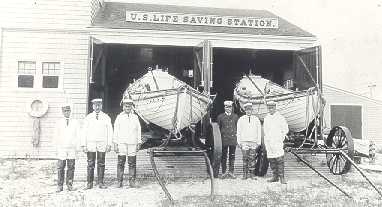

Search and Rescue

(Right:

the Salisbury Beach, Maryland, Life-Saving Station, crew, and surfboats,

circa 1900.)

(Right:

the Salisbury Beach, Maryland, Life-Saving Station, crew, and surfboats,

circa 1900.)

Ever since man has gone down to the sea in ships, great risks have been run to rescue those in danger. To improve the possibility of success, responsibility had to be delineated and means appropriated. In 1831 the Secretary of the Treasury directed the revenue cutter Gallatin to cruise the coast in search of persons in distress. This was the first time a government agency was tasked specifically to search for those who might be in danger. In 1837 Congress authorized the President "to cause ... public vessels ... to cruise upon the coast, in the severe portion of the season ... to afford such aid to distressed navigators as their circumstance and necessities may require; and such public vessels shall go to sea prepared fully to render such assistance." This addressed rescue on the high seas. Yet, during the age of wood and sail, most disasters occurred close into shore.

From colonial days, the coastal colonies, later states, had certain responsibilities for the salvage of goods tossed upon their beaches from shipwreck. Many states also imposed upon the salvagers the duty to rescue persons on board shipwrecked vessels as a prerequisite to obtaining salvage rights. Persons appointed by the states, called "wreckmasters," "commissioners of vendue," "commissioners of wrecks," etc., were specifically charged with assembling a volunteer boat crew at each wreck that occurred within the wreckmaster's jurisdiction for the purpose of rescue and salvage. These early efforts were closely tied to maritime interests at the large coastal ports of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.

The middle of the 19th Century was the era of the immigration packet. Small sailing ships were packed with several hundred immigrants in Europe. As these ships neared New York, nor'easters, which prevailed in the winter months, drove many of the crowded vessels aground on the New Jersey shore. There, but a few hundred yards from safety, the surf would pound the sturdiest craft to pieces and the freezing, tumultuous water would overcome the strongest swimmer. Many rescue attempts were made from shore under these circumstances but, on the average, only about half those people on board reached the beach alive. The losses were not for a lack of volunteers wishing to help but mostly because no means had yet been contrived to reach the wreck across the breaking surf and to retrieve the occupants of the stricken vessel.

An innovative solution was needed; techniques and equipment had to be developed in order to save those stranded so close to their new homeland. Beginning in 1848, a federal lifesaving service began to take shape. At first, the government provided a garage-like structure outfitted with rescue equipment. The coasts of New Jersey and Long Island had experienced the greatest numbers of wrecks with the result that these beaches were the sites for the new stations. The construction and equipping was a joint project carried out by a Revenue Marine officer, the boards of underwriters, and local citizens associated with salvage work. There was a fully-equipped iron boat on a wagon, a mortar apparatus for propelling a rescue line, powder and shot, a small covered "life car" for hauling in survivors, a stove, and fuel. The keys to the station were entrusted to a community leader, usually a wreckmaster, and he organized his volunteer crew.

There were successes - in 1850 the immigrant ship Ayrshire grounded during a snowstorm at Squan Beach, NJ. Under the supervision of wreckmaster John Maxon, the volunteers rescued 201 of the 202 persons on board. There also were failures. During the Civil War all save one of the iron surfboats were commandeered for use in the Hatteras Campaign. The remaining one was being used to slop hogs. Nevertheless, over the period 1848 through 1870 about 90% of the persons on board vessels wrecked within the scope of this Life-Saving Service survived.

Following

the war, in 1871, the Life-Saving Service was "reborn" under the

leadership of Sumner L. Kimball (right),

ably assisted by Revenue Marine Captain John Faunce (who had commanded Harriet

Lane at Charleston in 1861). New stations were built; new

equipment was developed; the scope of the Service was expanded beyond New

Jersey and Long Island and personnel were federalized.

Following

the war, in 1871, the Life-Saving Service was "reborn" under the

leadership of Sumner L. Kimball (right),

ably assisted by Revenue Marine Captain John Faunce (who had commanded Harriet

Lane at Charleston in 1861). New stations were built; new

equipment was developed; the scope of the Service was expanded beyond New

Jersey and Long Island and personnel were federalized.

Much

of the equipment and techniques developed during the mid-1800s continued in

use for a century. The Lyle Gun (left),

named for a Army captain, David A. Lyle, who devised it, typifies this. This

weapon of salvation was used to throw a line from the shore to a distressed

ship.

Much

of the equipment and techniques developed during the mid-1800s continued in

use for a century. The Lyle Gun (left),

named for a Army captain, David A. Lyle, who devised it, typifies this. This

weapon of salvation was used to throw a line from the shore to a distressed

ship.

Officers from the Revenue Marine played an important part in operations of the Life-Saving Service. Each Life-Saving Service District was assigned an Assistant Inspector, usually a first or second lieutenant, who reported to a Revenue Marine captain. He was assigned as the full-time Inspector of the Life-Saving Service. The inspectors performed training and administrative inspections, and conducted investigations in instances where lives were lost during shipwrecks.

In September 1888 the crew of Hunniwells Beach Station rescued fifteen persons from Glovers Rock in Maine. They had to lash the Lyle Gun on the afterthwart of their lifeboat and set the shotline box on the stern. The gun was loaded with a one-ounce cartridge of powder, and fired, casting the line almost into the hands of those in danger. Removing the people by breeches buoy was impossible due to the rocks; a small dory was rigged instead, and the fifteen people were hauled to safety. During the same storm, the crew of the Lewes (Delaware) Station, fired their gun from the upper window of a fish house, and landed the crew of the distressed craft in the loft with a breeches buoy.

Crews had to be able to perform their duties in the dark. On 3 February 1880 a storm wrought ruin upon the Jersey coast. At the height of the tempest, in the dead of night, Life-Saving crews rescued, without loss of life, the people of four ships. The beach apparatus was set up and worked in almost total darkness; the lanterns were thickly coated with sleet and were practically useless. The records of the Life-Saving Service are crowded with similar rescues.

(Right: the crew of the Neah Bay Life-Saving Station, circa 1910.)

The schooners Robert Wallace and David Wallace were wrecked at

Marquette, Michigan on 18 November 1886. The Ship Canal Station crew

traveled 110 miles by special train and rescued the ships' crews. In

three days' work on the Delaware Coast, 10-12 September 1889, the

life-saving crews at Lewes, Henlopen, and Rehoboth Beach Stations helped 22

vessels, and saved 39 persons by boat and 155 by breeches buoy without

losing a single life. The British schooner H. P. Kirkham was

wrecked on Rose & Crown Shoal on 2 January 1892. The crew of seven

was rescued after 15 hours exposure. The life-saving crew was at sea

in an open boat without food for 23 hours. There also were sacrifices.

Seven surfmen lost their lives going to the aid of the Italian ship Nuova

Ottavia on 1 March 1876.

The schooners Robert Wallace and David Wallace were wrecked at

Marquette, Michigan on 18 November 1886. The Ship Canal Station crew

traveled 110 miles by special train and rescued the ships' crews. In

three days' work on the Delaware Coast, 10-12 September 1889, the

life-saving crews at Lewes, Henlopen, and Rehoboth Beach Stations helped 22

vessels, and saved 39 persons by boat and 155 by breeches buoy without

losing a single life. The British schooner H. P. Kirkham was

wrecked on Rose & Crown Shoal on 2 January 1892. The crew of seven

was rescued after 15 hours exposure. The life-saving crew was at sea

in an open boat without food for 23 hours. There also were sacrifices.

Seven surfmen lost their lives going to the aid of the Italian ship Nuova

Ottavia on 1 March 1876.

Personnel from the Lighthouse Service and the Revenue Cutter Service also performed heroic rescues. On 31 December 1839, the schooner Deposit was driven onto the Massachusetts coast by hurricane winds. T.S. Greenwood, keeper of the Ipswick Lighthouse, tied a line around his waist and swam through the roaring surf to the doomed ship. He then pulled a surfboat with a colleague in it to Deposit and the pair rescued the wife of the ship's captain. In 1897-1898, crew members of the cutter Bear drove a herd of reindeer 2,000 miles as food for 97 starving whalers caught in the Arctic ice.

(Left:

Surfman Rasmus Midgett single-handedly rescued the crew of the wrecked Priscilla.)

(Left:

Surfman Rasmus Midgett single-handedly rescued the crew of the wrecked Priscilla.)

The beneficiary of search and rescue operations continually changed. From 1830 through 1870, the immigrant packet proved to be the most vulnerable. The introduction of steel, steam, and improved aids to navigation significantly reduced coastal disasters affecting large passenger vessels. These innovations introduced more shipping into the high seas, resulting in a shift in the area of operation for search and rescue activity involving vessels with large numbers of persons on board. Smaller coastal sailing vessels remained as the primary focal point for Life-Saving Service operations until the turn of the century.

From 1871 to 1914, 178,741 persons received the services of the "Life-Savers." Although some of these people faced minimal risk, only 1,455 individuals lost their lives while exposed within the scope of Life-Saving Service jurisdiction.

"Blue water" cutters, joined by flying amphibians in the 1930s, became primary rescue platforms. Regular trans-Atlantic air traffic was initiated just before World War II, introducing new clientele. Ocean Stations were established, first in the Atlantic and later in the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific. A cutter was stationed in mid-ocean to provide rescue sites and to report on weather. Increased aircraft reliability and improved electronics have removed the need for the stations and the last was disestablished in 1977.

"Search and Rescue" has been dramatically influenced by technology from that day in 1831 when the federal government assumed a responsibility. Ironically, during World War II the Coast Guard was charged with developing the helicopter for anti-submarine warfare. The Coast Guard trained all helicopter pilots, both British and American. As the submarine threat abated in 1944, the emphasis of helicopter development was changed from anti-submarine warfare to search and rescue.

Following World War II, the search and rescue scene shifted back to the tidewater, the new patron being the boating enthusiast. Pleasure craft grew in increasing numbers and the helicopter emerged as a primary rescue tool. Each era has required new equipment suited to the needs of that day.

(Left: a 44-MLB)

High-seas search and rescue has long presented the Coast Guard with one of

its greatest challenges. When disaster occurs, hundreds of lives may

be at stake. On 14 and 15 October 1947, 69 survivors were rescued by the

crew of the USCGC Bibb from the flying boat Bermuda Sky Queen,

waterborne in the North Atlantic Ocean, approximately midway between

Labrador, Canada and Ireland. In October 1980, while almost 200 miles

off Sitka, the Dutch cruise ship Prinsendam (right)

was jarred by explosions and stopped dead in

the water after a fire started in the engine room. In spite of rough seas

and strong winds, four Coast Guard, one Air Force and two Canadian

helicopters plucked more than 500 shipwreck survivors from crowded lifeboats

in the cold Gulf of Alaska. Many of the survivors, mostly senior

citizens, were lifted in rescue baskets to the awaiting Coast Guard Cutter Boutwell

and the commercial tanker Williamsburgh. Not one life was lost;

Prinsendam sank seven days later.

High-seas search and rescue has long presented the Coast Guard with one of

its greatest challenges. When disaster occurs, hundreds of lives may

be at stake. On 14 and 15 October 1947, 69 survivors were rescued by the

crew of the USCGC Bibb from the flying boat Bermuda Sky Queen,

waterborne in the North Atlantic Ocean, approximately midway between

Labrador, Canada and Ireland. In October 1980, while almost 200 miles

off Sitka, the Dutch cruise ship Prinsendam (right)

was jarred by explosions and stopped dead in

the water after a fire started in the engine room. In spite of rough seas

and strong winds, four Coast Guard, one Air Force and two Canadian

helicopters plucked more than 500 shipwreck survivors from crowded lifeboats

in the cold Gulf of Alaska. Many of the survivors, mostly senior

citizens, were lifted in rescue baskets to the awaiting Coast Guard Cutter Boutwell

and the commercial tanker Williamsburgh. Not one life was lost;

Prinsendam sank seven days later.

The 1980s and 1990s saw the US Coast Guard saved thousands responding to

numerous refugee boatlifts from Haiti (left,

during Operation Able Vigil) and Cuba (right,

during Operation Able Manner). On

November 24, 1995, for example, Dauntless rescued 578 migrants from a

grossly overloaded 75-foot coastal freighter, the largest number of migrants

rescued from a single vessel in Coast Guard history. This work has

continued into the new century, for example in the year 2000 alone, the

Coast Guard sortied 57,697 times and saved 3,400 lives.

The 1980s and 1990s saw the US Coast Guard saved thousands responding to

numerous refugee boatlifts from Haiti (left,

during Operation Able Vigil) and Cuba (right,

during Operation Able Manner). On

November 24, 1995, for example, Dauntless rescued 578 migrants from a

grossly overloaded 75-foot coastal freighter, the largest number of migrants

rescued from a single vessel in Coast Guard history. This work has

continued into the new century, for example in the year 2000 alone, the

Coast Guard sortied 57,697 times and saved 3,400 lives.

Preventive Safety

Safety at sea requires preventative and corrective measures. Too much is as bad as too little. A ship is similar to a delicately tuned instrument. If excessive cost and weight are devoted to safety, the ship will not be competitive and probably will never be built. Throughout the history of commercial vessel safety, there has been the constant struggle to provide a balance between the greatest degree of safety and reasonable cost.

The steam engine was married to the sailing ship in the early 19th century. Beginning in the second decade of that century, there was a series of shipboard boiler explosions, resulting in huge losses of life. Almost immediately two schools of thought concerning commercial vessel safety crystallized. There were those who favored strong federal regulations and those who opposed government interference into transportation. At first, the federal government followed a laissez-faire philosophy. Secretary of the Treasury Richard Rush remarked in 1825, "Legislative enactments are calculated to do mischief rather than prevent it...."

State governments attempted to establish safety standards for steam vessels; these due to the interstate nature of waterborne commerce. The catalyst for federal action occurred in 1837 when the steamboat Pulaski exploded in North Carolina; 100 lives were lost. Congress passed an act "For the better security of the lives of passengers." This was the birth of commercial vessel inspection. The act provided the installation of fire-fighting and life-saving apparatus. Enforcement was the weak link; district judges appointed local persons to be inspectors. Obviously, in this small blossoming industry, the local individual competent to pass judgment must have had close ties with the ship owners. Also, no standards were set. Each inspector used his own judgment as to what was the maximum steam pressure permitted, and so on.

(Left:

a Coast Guard naval architect inspects the plans of a new merchant ship;

right: a Coast Guard inspector inspects the generator control panel of a

passenger vessel.)

(Left:

a Coast Guard naval architect inspects the plans of a new merchant ship;

right: a Coast Guard inspector inspects the generator control panel of a

passenger vessel.)

The evolution of technology outstripped these mild legislative controls even though updated, and disasters continued. From December 1851 through July of the following year, there were seven major disasters, costing nearly 700 lives. Congress responded with the Steamboat Inspection Act of 1852. This expanded the responsibilities of the Act of 1838 and corrected the major flaw of the earlier law by controlling inspections and licensing. This new law had its shortcomings as well. Only steamships carrying passengers were subject to its provisions. Thus, steam tugs, freighters, canal boats were exempt from the provisions of the 1852 law, although still remaining subject to those of the 1838 one.

The Civil War diverted America's efforts from commercial vessel safety, as it had from life-saving, and an awesome price was paid. Fifteen hundred people perished on board the stern-wheeler Sultana in 1865 in the largest U.S. commercial maritime disaster. Sultana embarked nearly all of the 376 allowed passengers. Taking advantage of the wartime environment, 2,000 Union veterans, most of whom were recently freed prisoners of war, were also packed on board. While plying the river between Memphis and Cairo, Ill., a boiler exploded and the ship went up like a torch.

Future

disasters brought in sharp focus areas needing improved safety regulations.

Almost 1,000 lives were lost on General Slocum in 1904; as a result,

safety regulations and inspection equipment were improved. More than

1,500 lives were lost on Titanic in 1912; certification and

life-saving devices were improved. More than 100 lives were lost on

board Morro Castle (left) in

1934 and another 45 on Mohawk the following year. Partly as a

result of these two disasters, more marine legislation was passed in 1936

and 1937 than during the previous twenty years. To the novice,

commercial vessel regulations seem a reaction to disaster. In fact,

disaster has proven a catalyst for perfecting efforts previously undertaken.

Future

disasters brought in sharp focus areas needing improved safety regulations.

Almost 1,000 lives were lost on General Slocum in 1904; as a result,

safety regulations and inspection equipment were improved. More than