|

Explosion of

DeBruce

Grain

Elevator

Wichita, Kansas

8 June 1998 |

|

| Grain Elevator Explosion Investigation Team (GEEIT) |

Below is an Executive Summary of the report on the DeBruce Grain Elevator explosion. The report in its entirety is available by contacting OSHA's regional headquarters in Kansas City at (816) 426-5861, or by writing to :

U.S. Department of Labor

Occupational Safety and Health Administration

1100 Main Street, Suite 800

Kansas City, MO 64105

Cost is $5 for a CD, or $100 for a printed copy. Checks or money orders (no cash) should be made payable to "Secretary of Labor."

Report on

Explosion of

DeBruce Grain

Elevator

Wichita, Kansas

8 June 1998

Commissioned by the

US Department of Labor

Occupational Safety and Health Administration

Grain Elevator Explosion Investigation Team

(GEEIT)

Vernon L. Grose, D.Sc., Editor

Report Placed in Final Electronic Format

By David K. McDonnell of OSHA in Cooperation with GEEIT

Report Table of Contents

DE BRUCE GRAIN ELEVATOR EXPLOSION

Wichita, Kansas

8 June 1998

Chapter 1 ENGAGEMENT OF INVESTIGATORY EXPERTISE

Grain Elevator Explosion History

National Academy of Sciences

Analysis of Previous Elevator Explosions

GEEIT (Grain Elevator Explosion Investigation Team)

Sponsorship Rationale

Chapter 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF EXPLOSION

Elevator Description

Location of Victims

Fatalities

Injured

On-Site Uninjured

Physical Damage

Rescue Factors

Probable Causation

Chapter 3 DE BRUCE GRAIN ELEVATOR HISTORY

Construction Evolution

Physical Dimensions and Characteristics

Headhouse

Offices

Elevator Equipment

Galleries

Silo Tunnels

Crossover Tunnels

Lean-To and Flat Storage

Continuous Gallery-Tunnel Belts

Grain Dust Control

Previous Accidents

Chapter 4 DE BRUCE MANAGEMENT ROLE IN EXPLOSION

DeBruce Intent in Elevator Acquisition

Revision of Operational Philosophy

Outsourcing

Dust Removal Equipment

Manual Dust Removal

Elimination of Functional Crews

Personnel Training Objectives

Criteria for Equipment Repair and Upkeep

Continuous Gallery-Tunnel Belt Operation

Chapter 5 DE BRUCE OPERATIONAL ROLE IN EXPLOSION

Worker Knowledge of Elevator Operation

Powdered Grain Explosive Comprehension

Powdered Grain Control -- Man and Machine

Comprehension of Grain Dust Ignition Sources

Techniques for Identification

Ignition Relationship to Explosion

Work Assignments and Indoctrination

"Team" Concept v. Functional Crews

Increased Production Rate

Operational Start-Stop Responsibility

Worker Cultural and Language Diversity

Safety Awareness

Hazard Identification and Countermeasures

Periodic Refresher Exposure

Emergency Response Plans and Drills

Chapter 6 ELEVATOR STATUS AT EXPLOSION'

Psychological Factors

"Monday Morning" Syndrome

Harvest Season Startup

Illegal Drug Use

Grain Handling Equipment

Drags, Belts, and Augers

Elevator Legs

Dust Collection Systems

Dust Collection Effectiveness

State of Elevator Cleanliness

Electrical Systems

Weather

Chapter 7 GRAIN ELEVATOR EXPLOSION FACTORS

Fuel (Grain in Powdered Form)

Oxidizer (air)

Fuel-and-Oxidizer Containment

Fuel Dispersion in Air

Ignition

Chapter 8 ANALYSIS OF EXPLOSION

Background

PHYSICAL Evidence

WITNESS Testimony

Process of Analysis

Seeking Explosion Initiation

Witness No. 1

Witness No. 2

Witness No. 3

Narrowing the Search

Combining Physical Evidence with Witness Testimony

Determining the Initiating Location

Locating the Enabling Mechanism

The Ignition Identification Process

Ignition Source

Layered Dust Accumulations

Blast Pathways of Progression

South Silo Array

Headhouse

North Silo Array

Possible Detonation

Quantitative Analysis of Damage

Evidentiary Foundation of Analysis

Rescue Operations

Compromise Between Rescue and Destroying Evidence

Loss of Evidence

Site Jurisdiction

Chapter 9 WITNESS TESTIMONY

Intelligence Sought

Silent Witnesses

Surviving Witnesses

Hospitalized Survivors

Injured But Not Hospitalized Survivors

Eyewitness Accounts

Chapter 10 TRENDS IN GRAIN HANDLING

Grain Storage v. Transportation

Movement -- Not Storage

Politics, Economics and Weather

Impact of Grain Handling

Utilizing Grain Dust as a Product

Chapter 11 ECONOMICS OF GRAIN DUST

USDA Grading of Grain

Bizarre Business

Hazardous, Not Just Economic

World Market Pricing

Chapter 12 ROLE OF WORKERS COMPENSATION

Forfeited Recourse

Kansas Version

Corporate Advantage

Disaster Prevention Motive

Chapter 13 INVESTIGATION LESSONS LEARNED

Not-Invented-Here (NIH) Factor

Fear of Litigation

Access Confusion

Photographic Recording

Greatest Lesson Learned

DeBruce Learned a Lesson, Too

Chapter 14 PREVENTION OF FUTURE ELEVATOR EXPLOSIONS

Preexisting Conditions

Allowable Grain Powder

Grain Dust Generation

Re-Distributed, Not Collected

Lack of Equipment Maintenance

Historic But Abandoned Dust Control

Post-Explosion Fuel Availability

Grain Transfer Entries

Headhouse Pollution

Explosive Fuel in Galleries

Impact of Cleaning in South Gallery

Tunnel Filthiness

Tunnel Impact on Explosion Initiation

APPENDICES

A. Scientific basis for the analysis of the explosion

B. Industrial Maintenance, Inc. solicited proposals

APPLICABLE FEDERAL REGULATIONS

REFERENCES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

GEEIT MEMBERSHIP

Vernon L. Grose

Robert F. Hubbard

C. William Kauffman

Michael A. Polcyn

Ben F. Harrison

Thomas H. Seymour

Albert S. Townsend

List of Figures in the Report

DE BRUCE GRAIN ELEVATOR EXPLOSION

Wichita, Kansas

8 June 1998

Chapter 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF EXPLOSION

Figure 2-1: Aerial View of DeBruce Grain elevator Page 1

Figure 2-1: Aerial View of North Gallery, DeBruce Grain Elevator Page 4

Chapter 3 DE BRUCE GRAIN ELEVATOR HISTORY

Figure 3-1: Inside the Elevator Page 2

Figure 3-2: Floors of the Headhouse Page 4

Figure 3-3: 3,000' Continuous Gallery-Tunnel Belts Page 5

Chapter 4 DE BRUCE MANAGEMENT ROLE IN EXPLOSION

Figure 4-1: Major Components -- Dust Collection Page 6

Figure 4-2: Two View of Belt in South Gallery Page 14

Chapter 5 DE BRUCE OPERATIONAL ROLE IN EXPLOSION

Figure 5-1: Juan Prajedes Ortiz Signature in Grain Dust Page 4

Figure 5-2: Fault Tree Analysis of Grain Dust Explosion Page 7

Chapter 6 ELEVATOR STATUS AT EXPLOSION

Figure 6-1: Scale Office From Outside Headhouse Page 2

Figure 6-2: Front and Aft Views of Truck Unloading Page 5

Figure 6-3: Critical Equipment Page 7

Figure 6-4: Toppled Dust Bin at Elevator Headhouse Page 8

Table I: Weather Data: Wichita Internationl Airport Page 10

Chapter 7 GRAIN ELEVATOR EXPLOSION FACTORS

Figure 7-1: Two Perspectives of Accidental Catastrophe Page 2

Figure 7-2: Damage to East Side of Headhouse Page 5

Figure 7-3: Damage to End of North Silo Array Page 6

Chapter 8 ANALYSIS OF EXPLOSION

Figure 8-1: Blast Directional Signs in Tunnel No. 2 Page 5

Figure 8-2: Conveyor Roller As Ignition Source Page 7

Figure 8-3: Billowed Layers of Grain Dust on South Gallery Floor Page 9

Figure 8-4: Path of the Explosions Page 10

Figure 8-5: Damage on West Side of Headhouse Page 12

Figure 8-6: Scott Mosteller Awaiting Rescue on North Array Page 15

Figure 8-7: Wichita Fire Rescue Team Using Crane Page 15

Figure 8-8: Destroyed North Array Silos Page 16

Figure 8-9: Wichita Rescue Team Inside Headhouse Page 18

Figure 8-10: Helicopter Rescue of David Pickens Page 21

Chapter 14 PREVENTION OF FUTURE ELEVATOR EXPLOSIONS

Figure 14-1: Facets of the Systems Approach to Explosions Page 2

Chapter 1

ENGAGEMENT OF INVESTIGATORY EXPERTISE

Grain Elevator Explosion History -- Records of grain elevator explosions have been documented for over 120 years. However, they have probably occurred from the time that structures for handling large amounts of grain were first developed. Five elevator explosions in the United States in December 1977, resulting in 59 deaths and 48 injuries, raised concern in the Federal Government about how to reduce such disasters. This concern led -- as is often the case in issues of national concern that involve science, economics, and technology -- to calling on the National Academy of Sciences for an objective perspective.

National Academy of Sciences -- The Department of Agriculture engaged the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) in 1978 to conduct a symposium on grain elevator explosions. Following this symposium, the Department of Labor's Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requested the NAS to form the Panel on Causes and Prevention of Grain Elevator Explosions. Its membership was composed of experts in systems analysis, explosion dynamics, investigations and prevention, instrumentation, grain handling and processing, agricultural insurance practices, employee relations, dust control methods, and aerodynamics.

This Panel's work, completed in 1983, resulted in raising awareness in the grain handling industry of the hazards of grain dust as well as providing specific means of reducing those hazards. Based on that awareness and following extensive debate and Congressional hearings, OSHA issued regulations governing grain elevator operations which have resulted in a dramatic reduction in frequency and severity of elevator explosions during the past decade. The results are graphically shown in Section III of Appendix A, page 214.

Analysis of Previous Elevator Explosions -- From 1979 to 1981, the NAS Panel on Causes and Prevention of Grain Elevator Explosions investigated 14 grain elevator explosions in Iowa (1), Kansas (1), Minnesota (4), Missouri (1), Nebraska (4), North Carolina (1), South Dakota (1), and Texas (1). Twelve of the 14 primary explosions were followed by secondary explosions -- which generally caused most of the resulting damage. This on-site analytical work was the first known effort to develop and apply systematic methodology for investigating grain dust explosions.

Prior to this time, most insurance companies and elevator owners only sought to resolve the amount of policy coverage for loss recovery. Though many explosions were spectacular and even killed numerous people, public attention to them was short-lived. By the time causation was determined (if it ever was), it was seldom newsworthy because awareness of the disaster had already passed from public consciousness and concern.

While all 14 elevator explosions were unique in some respects, they had generic commonalties which readily led to universal but practical concepts on their prevention. The results of these investigations were published by the National Academy of Sciences in a series of documents which are listed in the References.

GEEIT (Grain Elevator Explosion Investigation Team) -- Following the DeBruce Grain elevator explosion on 8 June 1998, some members of the earlier NAS Panel on Causes and Prevention of Grain Elevator Explosions were contacted independently by various insurance companies and attorneys as well as OSHA to explore whether they might be willing to voluntarily regenerate the Panel to assist in investigating the DeBruce Grain elevator explosion in Wichita to determine causation as well as propose preventive measures. Two original Panel members were now deceased, but the remaining five members agreed to join together under a new title -- Grain Elevator Explosion Investigation Team or GEEIT. Specialists from Wilfred Baker Engineering in San Antonio were enlisted to replace expertise of the two deceased members.

Sponsorship Rationale -- The solicitation by several parties to engage and underwrite GEEIT expertise for the DeBruce Grain explosion presented a dilemma because those parties had differing -- if not conflicting -- interests in GEEIT findings and conclusions. After due consideration, GEEIT decided to accept OSHA sponsorship and provide its expertise to OSHA in the conviction that the broadest and most meaningful contribution to prevention of future explosions would be possible through OSHA's established regulatory framework. Though regulatory bodies like OSHA cannot prevent explosions -- only those parties who control the situation in which explosions occur can prevent them, GEEIT believes that government agencies provide the vital singular role of representing public interest and serving as the public's advocate for safe operation. Further, there was conviction that the traditional OSHA regulatory role could be enhanced if GEEIT provided an educational perspective on the disaster that would support future preventive work by OSHA.

Chapter 2

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF EXPLOSION

Elevator Description -- Reported in Guinness Book of Records as the world's largest grain elevator, the DeBruce Grain elevator was located approximately 4 miles southwest of Wichita, Kansas. Its storage capacity was 20.7 million bushels. Were the elevator to store wheat exclusively, it could have supplied the wheat for all the bread consumed in the United States for nearly six weeks.

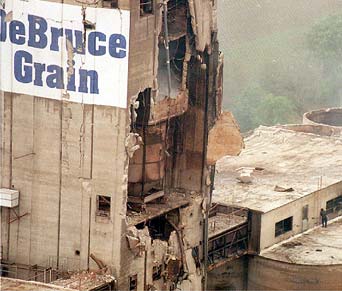

The elevator was laid out in a northeast/southwest direction, but for purposes of easy reference, it was generally described as though it was oriented north/south. Figure 2-1 is an aerial view taken of the east side of the DeBruce elevator within an hour after the explosion.

Figure 2-1

Aerial View of DeBruce Grain elevator

The elevator complex at the time of the explosion consisted of 246 circular grain silos (often also referred to as tanks or bins) that were 30' in diameter and 120' in height, arranged in a linear array of 3 silos abreast. The 164 star-shaped spaces between the circular silos were also used for grain storage and are known as interstice silos. There were therefore a total of 310 grain storage silos in the elevator.

Located midway between these 310 grain storage silos -- and separating them into a north array and a south array -- was a headhouse 216.5 feet high from its basement floor, standing 197 feet above ground. It was 42' square in cross-section and housed four elevator legs as well as facilities to weigh and distribute grain into selected silos. The overall length of the elevator -- headhouse and silos -- was 2,717 feet, well over one-half mile long.

Across the top of all these 310 silos were two 1,300' galleries, approximately 46' wide and 10' high -- one for the south silo array and the other for the north. Elevated grain was carried horizontally in each gallery by belt from the headhouse out to a selected silo and then dumped into that silo, using a "tripper" to divert the grain from the belt.

Beneath all the 310 silos were four 1,300' tunnels, approximately 7' high and 8' wide -- two under the north array of silos and two beneath the south array. These tunnels in this report are numbered. The tunnels in the south array are #1 and #2, in the north array #3 and #4, with #1 and #3 on the west and #2 and #4 on the east. The conveyor belt numbers coincide with the tunnel numbers. These tunnels contained belts that carried grain discharged from the silos toward the elevator legs in the headhouse. There the discharged grain was elevated and distributed into either a rail car or truck -- or returned to a silo (if the grain had been cleaned, fumigated or aerated).

Location of Victims -- Those who were killed or injured were located at the time of the explosion as described:

| Within west tunnel, south array: |

Four fatal |

| Outside west tunnel, south array: |

One fatal |

| Outside east side of headhouse: |

One fatal, one injured |

| Inside upper headhouse floors: |

One fatal, three injured |

| Inside south gallery: |

One injured |

| Outside end of south array: |

Three injured |

| Inside west office of headhouse: |

Two injured |

Fatalities -- A total of seven men were fatally injured in the explosion. They were employees of either DeBruce Grain or Labor Source Incorporated (LSI).

DeBruce Grain:

Jose Luis Duarte (41 years)

Howard Goin (65 years)

Lanny Owen (43 years)

Labor Source Incorporated (LSI):

Victor Manuel Castaneda (26 years)

Raymundo Diaz-Vela (23 years)

Jose Prajedes Ortiz (24 years)

Noel Najera (25 years)

Injured -- The ten men who were injured in the explosion were employees of four companies: DeBruce Grain, Labor Source Incorporated (LSI), Dusenbery Trucking, and Rob Heimerman Trucking.

DeBruce Grain:

Scott Mosteller (37 years)

David Pickens (21 years)

Johnny Sutton (46 years)

Labor Source Incorporated (LSI):

Carlos Amador (35 years)

Vladimir Martinez Duarte (24 years)

Miguel Rios (26 years)

Santiago Sergio Sola (30 years)

Daryl Williams (45 years)

Dusenbery Trucking:

Raymond Hamilton (58 years)

Rob Heimerman Trucking:

Bill Helms (40 years)

On-Site Uninjured -- There were ten people -- present on DeBruce property adjoining the elevator -- who survived the explosion. They were employees of four different companies. Most of them played roles in immediate search-and-rescue efforts. Their testimony was helpful and contributed to the GEEIT investigation.

DeBruce Grain::

Kelly Burtin

Brent Hultgreen

Denise Michelle Tiffany

Dale Lock

Steve Stallbaumer

Industrial Maintenance, Incorporated:

Roger L. Heath

Tom McHugh

Rodney L. Schumock

Lange Company:

Eric Mingle

Dusenbery Trucking:

Bill Dusenbery

Physical Damage -- Beginning in the east tunnel of the south array of silos, a series of explosions -- utilizing a crossover tunnel -- were propagated both directions in the two tunnels of the south array. Upon reaching the headhouse via both south tunnels, blast and fire blew upward through the headhouse, and into the south gallery from the headhouse for only a short distance. Because grain dust in that gallery near the headhouse had just been cleaned, the blastwave separated from the trailing fireball causing the latter to self-extinguish. However, although most of the south gallery thereon south remained integral, there was more than ample grain dust available -- had there been an ignition source -- to have destroyed the remainder of the south gallery.

However, that same blast wave and fire also moved out from the headhouse into the north gallery where it continued while also diverting downward through empty silos into the west north tunnel where it was diverted both south back into the headhouse basement and north to the exit, passing the cross tunnel where it propagated to the east north tunnel and where it went both north to the exit, and south to the headhouse.

As blast waves passed northbound beneath silos in both the north array tunnels, they rose vertically through those silos to the north gallery (most of which was destroyed) and blew off many silo tops as shown in Figure 2-2. In addition, numerous silos in both south and north arrays -- particularly those which were empty -- were destroyed by blast and fire. The 21-story headhouse -- shattered from bottom to top -- had to be torn down without being as thoroughly accessed and investigated by GEEIT for additional clues of blast direction and propagation within it as was desired.

Figure 2-2

Aerial View of North Gallery, DeBruce Grain Elevator

Most of the silo sheet-metal discharge spouts -- known as blast gates -- that release grain onto tunnel belts were either blown away or disabled so that all four tunnels were nearly choked with spilled grain. The force of successive explosions was sufficient to pulverize much of the structural concrete rather than simply break it into large chunks as usually occurs in grain elevator explosions of lesser severity. This effect was greatest at the north end of the elevator because of the large L / D (gun barrel) effect.

Rescue Factors -- Lack of worker knowledge of a DeBruce Grain Emergency Action Plan (because it existed only on paper and had neither been described to nor rehearsed with workers) -- coupled with absence of documented work assignments for all personnel (DeBruce Grain as well as independent contractors and trucking firms) working in the elevator at the time -- precluded early accountability for the number of affected personnel as well as their possible location within the elevator property.

Though local fire and rescue response was on-scene within 10 minutes after the explosion, considerable delay in implementing their efforts occurred due to identifying both the number of affected people and where they might be found within the vast, badly damaged, and burning conglomerate. In addition, there were widely-expressed but erroneous beliefs that additional explosions were to be expected. So great caution occurred -- even in rescuing and treating badly injured survivors in and near the elevator.

The immensity of the elevator structure (height, length, and limited access) presented rescuers and those performing triage with great challenges. The most severely injured had to be lifted from the top of 120' silos where they had either managed to escape on their own or where they had been assisted by rescue crews. A local company immediately sent its large crane to assist in lifting victims from the top of the elevator silos. A US Army helicopter flew 120 miles from Fort Riley, Kansas to the scene to lift an injured worker from the elevator gallery roof. After about four hours, all survivors within the elevator had been lifted by either crane or helicopter.

President Clinton declared Sedgwick County, in which the elevator was located, a federal emergency the day after the explosion. This designation released the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to dispatch 20 trained searchers to the scene along with 42 support personnel.

Because one victim's body was not located for weeks following the explosion, rescue activities were prolonged for five weeks before gradually being converted into recovery operations -- whereupon FEMA's Urban Search and Rescue team of over 60 personnel departed for their home base in Lincoln, Nebraska.

Probable Causation -- No grain elevator explosion has a singular cause. As elaborated in Chapter 7, there are five components of every such explosion -- often described as the Explosion Pentagon: fuel (powdered grain), oxidizer (air), fuel-and-oxidizer containment within a closed volume (elevator), dispersion of fuel-and-oxidizer mixture within the limits of explosivity, and ignition. Without any question, all five of those factors happened simultaneously on 8 June 1998.

The initial DeBruce Grain elevator explosion -- which set off a series of additional explosions of increasing severity -- occurred when grain dust was ignited in the east tunnel of the south array of silos. The most probable ignition source was created when a concentrator roller bearing, which had seized due to no lubrication, caused the roller to lock into a static position as the conveyor belt continued to roll over it. This "razor strop" effect on the roller raised its temperature to 260°C, well beyond the 220°C required to ignite layered grain dust which was plentiful inside the roller.

Because the belt was running in that tunnel at the moment of explosion it was creating a convective airflow. Witnesses reported that during elevator operation that the cloud of suspended grain dust was often so thick that during these times one could not see their hand in front of their face. The dispersion of the smoldering dust contained within the conveyer roller and its impact upon the floor dust layer, which would raise additional dust to also be dispersed by the convective flow would produce an ample fuel oxidizer mixture to be ignited by the glowing embers.

But it would be an error to focus on the details of likely ignition as the reason the elevator was destroyed. Of far greater consequence in causing the explosion -- and the key to preventing a similar one in the future (which should be the primary purpose for investigating any accident) -- are the deliberate DeBruce corporate decisions to (a) allow massive amounts of fuel to continually be created and distributed throughout the elevator -- awaiting any one of many possible sources of ignition, (b) forego repair and restoration of long-failed grain dust control systems, and (c) abandon preventive maintenance of elevator equipment -- particularly the grain conveyor and grain dust control systems. These three factors -- voluntarily exercised by DeBruce in opposition to widely-known and recognized methodology for explosion prevention -- caused the catastrophe. All three, which were well within DeBruce cognizance and control, made the disaster an inevitability. |