|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

THE NATION’S FISCAL OUTLOOKThe President’s 2008 Budget addresses the Nation’s near-term and long-term fiscal challenges through pro-growth economic policies and spending restraint. Three years ago, the President set a goal to cut the deficit in half by 2009 from its projected peak in 2004. The President’s fiscal approach succeeded, and the results—including two consecutive years of double-digit revenue growth—allowed the President to achieve that goal in 2006, three years ahead of schedule. The Administration’s fiscal strategy of pro-growth tax policy, restraint in discretionary spending, and reductions in the growth of entitlement spending, will further reduce the deficit and balance the budget by 2012. This steady improvement in the deficit outlook is welcome news. Yet despite this improvement in the near term, the Nation continues to face pressing long-term fiscal challenges arising from our key entitlement programs. The President has made clear that he wants to work with the Congress to address this longer-term problem of the unsustainable growth in entitlement spending. THE NEAR-TERM FISCAL OUTLOOKSince the beginning of his Administration, the President has pursued pro-growth economic policies to give all Americans the opportunity to share in the Nation’s prosperity. Strong economic growth is also essential to generating the revenue needed to reduce the deficit. The President has pursued spending restraint in the face of enormous challenges, from the significant costs arising from the September 11th terrorist attacks and the subsequent War on Terror, to the response and rebuilding after Hurricane Katrina.

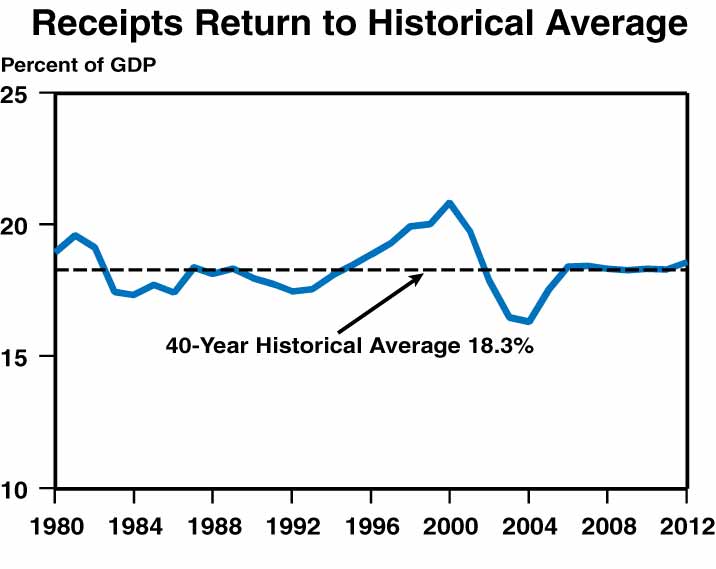

The size of the deficit and the debt is best assessed in relation to the economy as a whole, as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In his 2005 Budget, the President set a goal to cut the deficit in half by 2009 from its projected peak in 2004. The President achieved his goal in 2006, three years ahead of schedule. The deficit fell from a projected 4.5 percent of GDP, or $521 billion, to 1.9 percent of GDP, or $248 billion. This deficit is below the 40-year historical average of 2.4 percent of GDP, and is smaller than the deficit as a percent of GDP in 18 of the previous 25 years. The Budget reflects the projected full costs of the War on Terror for 2007 and 2008. It also includes an allowance for at least a portion of the anticipated costs for 2009; actual funding needs will be determined by conditions at that time. In addition, the Budget assumes the extension for one year of relief from the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT). Even with these added costs, the deficit is projected to decline in both dollar terms and as a share of the economy in 2007. By 2012, the Budget is projected to generate a surplus of $61 billion. The Budget projects these results while increasing funding for the Nation’s security, investing in education and supporting other key national priorities, including making permanent the President's tax relief.

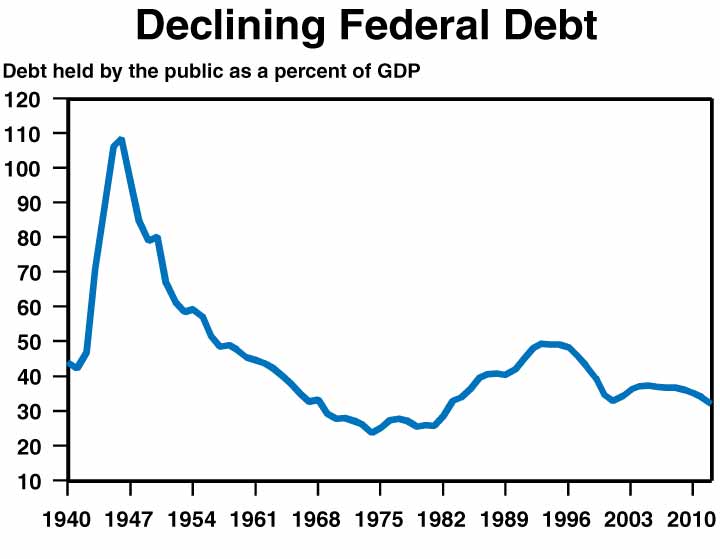

The Nation’s fiscal outlook is reflected in both the annual budget deficit and the amount of Federal debt held by the public, which is debt issued to finance past and current deficit spending. Debt held by the public has ranged from 33 to 49 percent of GDP over the past 20 years, and has averaged 35 percent over the past 40 years. For 2006, debt held by the public declined from 37.4 percent to 37.0 percent of GDP. For 2012, debt held by the public is expected to be 32 percent, below the 40-year historical average, providing further evidence that the President’s pro-growth economic policies and spending restraint are working to improve the Nation’s fiscal outlook. Strong Economy: Fueled by Pro-Growth PoliciesThe President’s pro-growth economic policies, beginning with his tax relief proposals, have promoted America's entrepreneurial spirit, rewarding the hard work and risk-taking of the Nation’s workers and entrepreneurs. The tax relief included reducing marginal individual income tax rates, doubling the child tax credit, reducing the marriage penalty, reducing capital gains and dividend tax rates, encouraging retirement savings, reducing the estate and gift tax, and increasing incentives for small business investment. On May 17, 2006, the President signed the Tax Increase Prevention and Reconciliation Act of 2005, extending through 2010 capital gains and dividend tax rate relief and extending through 2009 a provision to encourage small business investment by raising the expensing limits for equipment purchases. On August 17, 2006, the President signed the Pension Protection Act of 2006, tightening the rules relating to defined-benefit plans and making permanent some of the President’s proposals to encourage retirement and education savings.

Because of the positive economic impact his tax relief program has had in the short term, and would continue to have over the long term, the President’s policy is to make tax relief permanent rather than allowing it to expire as scheduled at the end of this decade. Since the President’s tax relief was fully implemented in 2003, the Nation’s economy has generated more than seven million jobs. This strong economic growth has been good for the Nation’s workers and the resulting revenue growth has been good for the Federal budget.

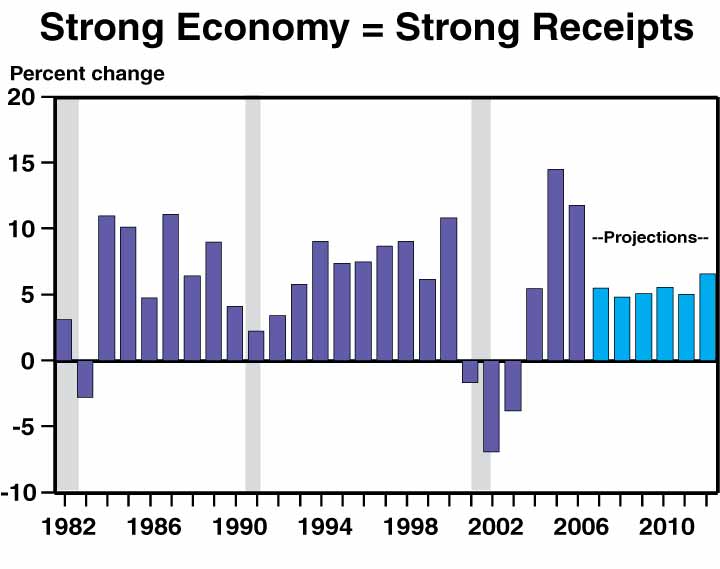

For 2006, tax receipts of $2.4 trillion were 11.8 percent greater than in 2005, and in 2005 receipts were 14.5 percent higher than in 2004. Each year constituted record receipts and together made for the highest two-year percentage growth in receipts in the past 25 years. The Budget conservatively projects future revenue growth that averages 5.4 percent over the next six years, about equal to the projected overall growth in the economy. The tax proposals in the 2008 Budget promote continued economic growth and, consequently, continued growth in the Government’s tax receipts. The Budget proposes to make permanent tax relief that was enacted in 2001 and 2003. In addition, the Administration proposes to change the tax code to encourage savings for retirement, to make it easier for all Americans to afford health insurance, and to increase small business investment. Furthermore, the Administration proposes to simplify the tax code for families, close tax loopholes, and increase tax compliance. In addition to tax relief, the President will continue to strengthen the economy by advancing basic research and development, promoting innovation and accountability in education, reducing the burden on business of Government paperwork and regulations, reducing costly and unnecessary litigation, and eliminating trade barriers and opening overseas markets to American products and services. National Security Spending: Protecting the American PeopleSecurity spending includes spending for the Department of Defense, homeland security, and international diplomatic efforts. International affairs spending finances efforts to create a stable government in Iraq, rebuild the economy in Afghanistan, and enhance security by promoting democracy and building alliances around the world. Between 2001 and 2006, security spending increased 41 percent overall: 36 percent for defense, 38 percent for international affairs, and 209 percent for homeland security. These significant increases were necessary to protect the Nation’s homeland and pursue the War on Terror after September 11th. In his 2008 Budget, the President includes a further 10.5 percent increase in base defense spending. This includes funding to maintain a high level of military readiness to support the Global War on Terror and to continue to transform the military to meet the challenges of the 21st Century. The Budget includes a 17.1-percent increase in spending for international affairs to support key allies in the Global War on Terror, promote democratic institutions and values, counter the spread of HIV/AIDS, and provide humanitarian assistance to those affected by continuing violence and instability. In addition, the Budget includes a 6.7-percent increase to defend the Nation’s homeland by funding nuclear detection capabilities, strengthening the country’s borders, developing high-tech screening capabilities, and maintaining close partnerships with State and local law enforcement officials. Spending Restraint: Slowing Growth in Non-Security and Entitlement SpendingThe near-term budget outlook has improved in large part because of the double-digit growth in tax receipts and also because of spending restraint. Due to the need for increased spending on defense and homeland security as part of the Global War on Terror and the automatic increases in spending for entitlement programs, outlays rose to $2.7 trillion in 2006, or 20.3 percent of GDP. Despite these spending pressures, spending remained below the 40-year historical average of 20.6 percent of GDP. This is largely because over the past two years, the Congress and the President have reduced the growth rate in non-security discretionary spending—which grew by more than 16 percent in the last year of the previous Administration—to below the rate of inflation. In addition, in February 2006, the Congress enacted and the President signed into law the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, generating nearly $40 billion in mandatory savings over five years. The 2008 Budget achieves spending restraint by holding growth in non-security discretionary spending to one percent in 2008 and for the five-year period. The Budget reduces or eliminates 141 programs saving $12.0 billion, and slows spending growth through sensible reforms in entitlement and other mandatory programs, resulting in savings of $96 billion over five years, and growing to savings of $309 billion over 10 years. This total includes $66 billion in savings in Medicare and $6.8 billion in Medicaid and the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) over five years, as discussed below. The Budget also proposes to increase premiums paid to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) by corporations with defined-benefit pension plans, providing $5.5 billion over five years to put the PBGC on a path to solvency. And, the Budget proposes to increase user fees, saving $7 billion over five years, to capture more fully the costs to the Government of providing particular goods and services. THE LONG-TERM OUTLOOK

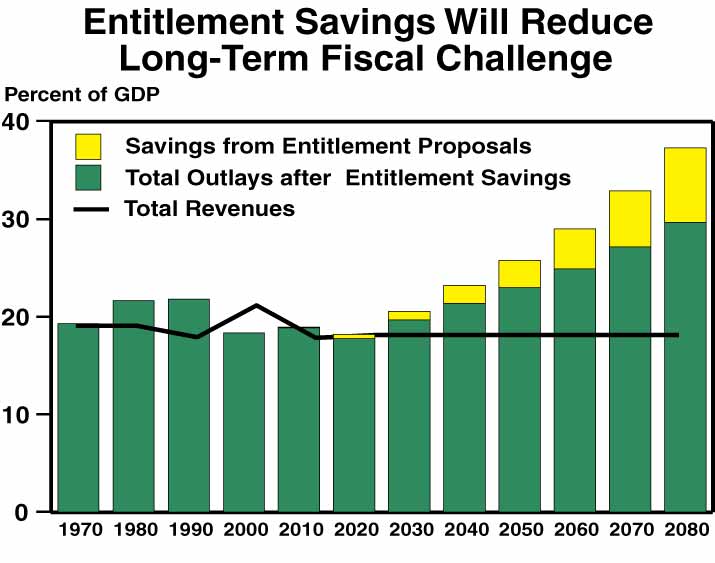

While the near-term outlook of smaller deficits and a surplus starting in 2012 is encouraging, the current structure of the Federal Government’s major entitlement programs will place a growing and unsustainable burden on the budget in the long-term. Currently, spending on Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security is approximately eight percent of the Nation’s GDP. With the first of the baby boom generation becoming eligible for Social Security in 2008, Social Security spending will accelerate. Three years later, the problem will become more pronounced as these individuals become eligible for Medicare, under which program costs rise even faster due to health care inflation. By 2050, spending on these three entitlement programs is projected to be more than 15 percent of GDP, or more than twice as large as spending on all other programs combined, excluding interest on the public debt. The mandatory savings proposals in the 2008 Budget will not solve the Government’s long-term fiscal challenges, but they are an important and meaningful step, producing a significant improvement over the long term. Under the President’s Budget policies, the deficit in 2050 is projected to be 4.7 percent of GDP. In contrast, if the Congress fails to adopt the President’s mandatory proposals and permits current law to remain in force, the deficit in 2050 is projected to be 7.5 percent of GDP. A more detailed analysis of the Government’s long-term fiscal outlook is provided in the Stewardship chapter of the Analytical Perspectives volume of the Budget. Social Security: Promised Benefits Outpacing ResourcesSocial Security was designed as a pay-as-you-go, self-financing program whereby current workers pay taxes directly and indirectly, through their employers, to support the benefit payments for current retirees, disabled persons, and survivors (collectively, beneficiaries). Such a system can only be sustained if the number of workers and the taxes they pay align with the number of beneficiaries and the benefits they receive. In 1950, when there were 16 workers for every program beneficiary, the combined payroll tax rate was very low at 3 percent of taxable wages. Currently, there are 3.3 workers for every beneficiary and the tax rate is 12.4 percent. The ratio of workers to beneficiaries is expected to decline further as the first of the baby boom generation becomes eligible for Social Security in 2008, and will fall to 2.2 workers per beneficiary in 2030.

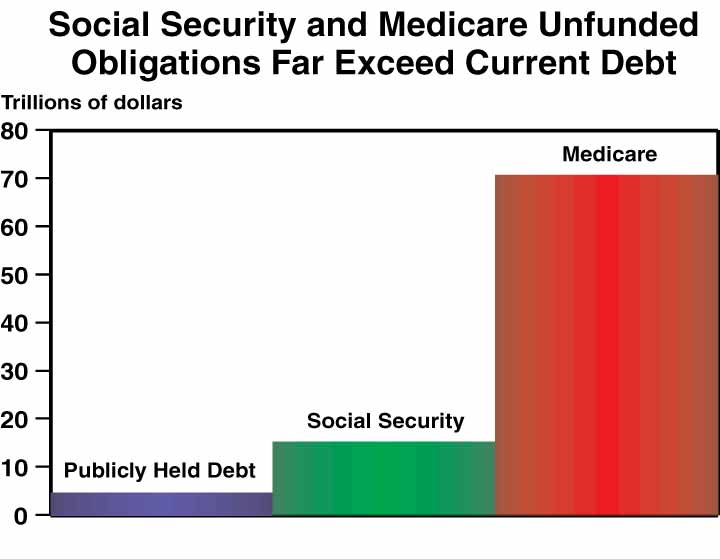

Even after the baby boom generation is fully retired, the ratio of workers to beneficiaries will continue to fall, reaching 1.9 in 2080 primarily because of the growing difference between projected life expectancy and the age at which seniors become eligible for Social Security benefits. The increase in longevity, coupled with the fact that Americans are spending fewer years in the workforce, means that Americans are spending a greater proportion of their lives in retirement than ever before. Since 1940, life expectancy at age 65 has increased by approximately 40 percent and is projected to increase by an additional 20 percent by 2080. The growth in retirees resulting from the retirement of the baby boom generation and increases in life expectancy will create a large and rapidly growing mismatch between scheduled Social Security benefits and the resources available to the program under current law. Through 2016, Social Security is projected to collect more in cash receipts than it pays in benefits. Beginning in 2017, however, Social Security benefit payments are projected to exceed the cash income dedicated to the trust funds. From this point forward, the Federal Government must borrow, tax, or cut other spending to pay excess Social Security benefits. Receipts are projected to continue falling to 70 percent of promised benefits by 2080. There are many ways to summarize the extent of the mismatch between expected Social Security receipts and benefits. One such summary is the discounted present value of all future scheduled benefits net of receipts, or unfunded obligations under Social Security. The concept is to compare scheduled benefits and receipts under current law into the indefinite future, and to recognize through discounting that a dollar tomorrow is worth less than a dollar today. Based on the 2006 Social Security Trustees’ Report, the unfunded obligation of Social Security totals $15.3 trillion over the indefinite future. To put this figure into perspective, this is about three times the amount of Federal debt currently held by the public. The President is committed to strengthening Social Security through a bipartisan reform process in which participants are encouraged to bring different options for strengthening Social Security to the table. The President has identified three goals for reform: to strengthen permanently the safety net for future generations without raising payroll tax rates; to protect those who depend on Social Security the most; and to offer every American a chance to experience ownership through voluntary personal retirement accounts. The 2008 Budget again reflects the President’s proposal to allow workers to use a portion of the Social Security payroll tax to fund voluntary personal retirement accounts. These accounts will permit Americans to have greater control over their retirement planning, giving them an opportunity to obtain a higher return on their payroll taxes than is possible in the current Social Security system. The result will be to shift Social Security from an entirely pay-as-you-go system of financing toward a system that is less dependent on current workers. Beginning in 2012, workers will be allowed to use up to four percent of their Social Security taxable earnings, up to a $1,300 annual limit, to fund their personal retirement accounts; the $1,300 cap will be increased by $100 each year through 2017. As one component of reforms to make the system sustainable, the President has embraced the idea of indexing future benefits of the highest-wage workers to inflation while continuing to index the wages of lower-wage workers to wage growth. Over time, wages tend to rise faster than prices, and so “progressive indexing” provides a higher rate of indexing for lower-wage workers than for higher-wage workers. This proposal would help restore the solvency of Social Security, while protecting those who most depend on Social Security. Comprehensive Social Security reform including personal retirement accounts, changes in the indexation of wages, and other modest changes will ensure the sustainability of the program for future generations, and help slow the unsustainable growth in total entitlement spending. Health Care: Reforms to Improve Quality and Reduce CostThe Nation spends more than $2 trillion per year on health care, permitting Americans to live longer and healthier lives than at any time in the Nation’s history. The Federal Government is the Nation’s largest purchaser of health care, accounting for approximately one-third of U.S. health care spending. As a result, economic developments in the health care sector, including the high rate of growth in health care inflation that confronts individuals and companies, are becoming acute fiscal problems for individuals and businesses, and for the Federal Government. Despite an enormous investment and enormous gains in the quality of care overall, health care inflation, the extent of private health care insurance coverage, and gaps in the availability of high-quality care are problems the Nation continues to face. The 2008 Budget proposes a number of reforms to improve the Nation’s health care system. The Administration is proposing a significant change in the tax treatment of health insurance purchases and expenditures for out-of-pocket health care costs. Under this proposal, all individuals and families who buy at least a catastrophic health plan will receive the same tax benefits, in the form of a flat $15,000 deduction. The Administration’s proposal will make health insurance more affordable for millions of American families and reduce the number of the uninsured. This policy will also eliminate the tax bias toward high-cost insurance, making health care purchasers more price conscious and thereby marshalling market forces more effectively to restrain health care inflation. The Administration continues to promote the use of health information technology to enhance the health care delivery system, including the availability of price and quality information to individuals. This would allow health care consumers to spend their health care dollars more wisely, and avoid unnecessary procedures and treatments. The President has also asked the Secretary of Health and Human Services to work with the Congress and the States on an Affordable Choices Initiative to redirect existing resources in the health care system to help poor and hard-to-insure citizens afford private insurance. This initiative would help avoid costly and unnecessary emergency room visits and improve health care quality and efficiency. Medicare: Slowing Cost Growth through ReformsThe single largest fiscal challenge we face is the unsustainable growth in the Medicare program. The Medicare Part A Hospital Insurance program receives designated payroll taxes from employees and their employers, which are deposited in the Medicare trust fund held by the Government. Medicare Part A is therefore similar to Social Security in that it is an inter-generational transfer program with current workers paying benefits for current beneficiaries. In contrast, under Medicare Part B, the Supplementary Medical Insurance program, and Part D, the new drug benefit, beneficiaries pay premiums to cover some of the costs and the balance is paid out of general revenues. As in the case of Social Security, Medicare will face increased cost pressures over the next several decades as the baby boom generation becomes eligible for and receives Medicare benefits. But because of rising health care costs, Medicare is projected to have much higher cost-per-beneficiary growth than Social Security in the coming decades. Medicare’s dedicated revenues from designated payroll taxes and from premium payments cover only 57 percent of current benefits. The remaining 43 percent is financed from general tax revenues. By 2030, the pressure from Medicare on general revenues will be substantially greater as dedicated revenues are projected to finance only 38 percent of total benefits, leaving 62 percent of program costs relying on general tax revenues. This projected rate of growth in Medicare benefits is not sustainable over time.

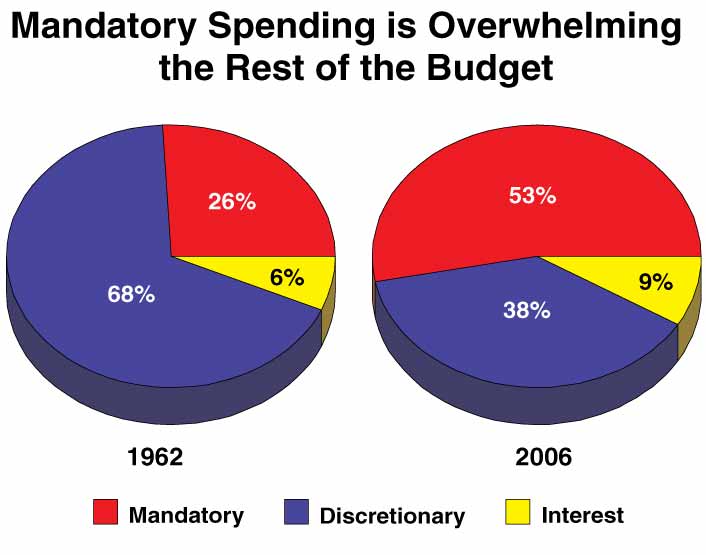

The 2006 Medicare Trustees’ report shows that future dedicated payroll taxes and premiums are sufficient to cover only a portion of Medicare’s projected costs. This results in an unfunded obligation (the gap between dedicated receipts and projected costs) of $71 trillion over the infinite horizon. This is more than four times as large as the gap between receipts and projected costs for Social Security and 14 times as large the total amount of Government debt that is held by the public. Within Medicare, the Hospital Insurance trust fund, which is mostly funded by the Medicare payroll tax, has unfunded obligations, or a gap between dedicated receipts and projected costs, of $28 trillion. Meeting these obligations would require tripling the Medicare payroll tax. If the Medicare payroll tax were used to pay for Medicare’s entire $71 trillion unfunded obligation, the Medicare payroll tax would have to be increased by 500 percent. This would be a huge tax increase on workers and companies that would cripple the Nation’s economy. The only realistic solution is to reduce program growth to a sustainable level. In the long run, part of the solution to Medicare and Medicaid’s unsustainable growth must lie with slowing health care inflation. Recent trends in the overall health care market have already improved Medicare’s finances. Spending on the Medicare drug program has been lower than originally expected because of lower-than-projected growth in prescription drug inflation. Medicare drug program spending in 2006, the first year of the benefit, was $15 billion lower than initially estimated. In addition, the drug program spending for 2007 is projected to be $25 billion lower than initially estimated, and for 2007 through 2016 the spending is projected to be $189 billion lower. The slower growth in prescription drug prices has been good for beneficiaries as well. Beneficiary premiums for the drug benefit are lower than expected: an average of $22 per month in 2007 rather than $39 per month as initially estimated. Controlling health care inflation is critical to the success of reform, but other significant reforms are also needed. With an unfunded obligation of $71 trillion, and annual increases in spending well above inflation and other domestic spending, there has been increasing focus on the need to address Medicare growth rates. The 2008 Budget proposes to restrain Medicare spending both in the near term and in the long term. These proposals save $66 billion over five years and reduce the present value of future net costs by an estimated $8 trillion over 75 years. These are sensible reforms, most of which have been proposed in previous budgets. The aggregate impact of the proposed reforms only slows the rate of growth of the Medicare program from 7.4 percent over 10 years to 6.7 percent. To achieve these savings, the Budget proposes to promote high-quality and cost-efficient care through competition and innovation. Specifically, the Budget proposes to adjust permanently provider payments to encourage efficiency and productivity, taking advantage of advances in medical technology and the delivery of care, and other management improvements. The Budget also proposes to establish competitive bidding for clinical laboratory services. The Budget also proposes to encourage greater responsibility for health care use and costs for high-income beneficiaries. In addition, the Budget proposes to modernize and rationalize Medicare policies to encourage efficient and cost-effective payments. For example, the Budget proposes to ensure that patients are served in the most medically appropriate and cost-efficient setting for post-acute care, and that payments for medical equipment be brought in line with actual costs. In addition to proposing specific reforms to reduce the unsustainable rate of growth in the near term, the Budget also proposes a new mechanism to address the long-term funded unfunded obligation in Medicare. The Budget proposes to build on the progress made in the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA) with respect to Medicare financing. Under current law, MMA requires the Medicare Trustees issue a “funding warning” if, for two consecutive years, the Trustees find that more than 45 percent of projected Medicare expenditures will require funding from general tax revenue (rather than dedicated resources) within the next six years. In the 2006 Trustees’ Report, the Trustees found that general revenue funding would first reach the 45 percent level in 2012, within the seven-year window specified in the MMA. The 2008 Budget proposes to add an incentive for reform to the MMA funding warning. Specifically, in the year in which the 45 percent threshold is exceeded, there would be automatic payment reductions to providers by four-tenths of one percent per year. The provider payments would continue to be reduced by an additional four-tenths of one percent per year, as long as Medicare’s receipts cover 55 percent or less of program costs. The provision is intended to encourage the Congress and the Administration to reach agreement on reforms needed to slow the growth in program costs. Medicaid: Proposals Ensure Fiscal IntegrityMedicaid is the Federal entitlement program that provides medical assistance, including acute and long-term care, to low-income families with dependent children and to low-income individuals who are elderly, blind, or disabled. As with Medicare, Medicaid costs will increase substantially in the coming decades as the baby boomers retire and begin to have greater health care needs. An increasing number of low-income elderly individuals will come to rely on Medicaid for non-hospital care, including long-term care. In addition, as with Medicare, Medicaid will be under increasing fiscal pressure in the coming decades as a result of health care inflation. The President’s Budget proposes a package of program integrity reforms. These reforms save approximately $6.8 billion over five years, including additional increased funding for the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). The Budget builds on previous initiatives, some of which were included in the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, to promote sound financial practices, increase market efficiencies, and eliminate Medicaid overpayments. The proposals included in the 2008 Budget help to ensure the fiscal integrity of Medicaid by lowering its rate of growth. These proposed changes reduce the rate of growth of Medicaid from 7.7 percent to 7.6 percent over the next 10 years. BUDGET REFORMSDuring the 1990s, budget decisions were governed by the now-expired Budget Enforcement Act (BEA). Under the BEA, discretionary spending (including both budget authority and actual outlays) was limited each fiscal year to a maximum amount specified in law. In addition, under the BEA, pay-as-you-go rules required all legislation involving new mandatory spending or tax cuts was required to be deficit neutral. Violations of the discretionary spending caps or the pay-as-you-go provisions triggered across-the-board spending reductions. The BEA generally succeeded in preventing the Government’s budgetary outlook from deteriorating. Based in part on the spending controls in the BEA, the President has proposed a number of budget process reforms, including new caps on discretionary spending, a pay-as-you-go requirement for mandatory spending, a line-item veto, and earmark reform. In addition, the Administration implemented its own pay-as-you-go controls to limit mandatory spending resulting from agency administrative action. Specifically, on May 23, 2005, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) began requiring that proposed agency administrative action that increases mandatory spending be offset by administrative actions that reduce mandatory spending by the same amount. Federal spending is generally divided into three major categories: discretionary spending (approximately 38 percent of the Budget), mandatory spending (53 percent), and interest on the debt (9 percent). Discretionary Spending Caps: Restraining Annual AppropriationsDiscretionary spending is generally thought of as funding the day-to-day operations of Government and is the only spending subject to annual review and appropriations by the Congress and the President. As distinct from mandatory spending, discretionary spending must be enacted into law every year before Government agencies may obligate and spend money. Hence, discretionary spending is not subject to the same automatic, uncontrolled growth characteristic of some mandatory spending. Nevertheless, without active restraint reinforced by effective rules governing the legislative process, discretionary spending will tend to increase steadily over time. The 2008 Budget proposes to reinstate BEA controls on discretionary spending. Specifically, the Budget proposes placing statutory limits or “caps” on discretionary spending each year through 2012. Any appropriations bill that causes the caps to be exceeded would be subject to a point of order, requiring a three-fifths vote, in the Senate. If, in the aggregate, appropriations actions exceed the spending caps, then OMB would be required to make across-the-board cuts to reduce total discretionary spending to the statutory caps. Within these proposed spending caps, the Budget proposes to devote resources for program integrity efforts. Program integrity efforts are designed to eliminate spending to those not eligible for benefit payments and to collect unpaid taxes due to the Government. Since program integrity efforts can generate as high as a ten-to-one return to the Government, the Administration proposes an adjustment to the statutory discretionary spending limits for amounts dedicated to program integrity. Mandatory Spending Controls: Restraining Automatic SpendingThe vast majority of spending for mandatory programs takes place automatically every year without any action on the part of the Congress or the President. It is made up of “entitlement” programs, for which the amount of spending is based on the number of qualifying beneficiaries and benefit formulas specified in law. This spending provides income security and health care to individuals who are elderly, disabled, widowed, or orphaned. These programs are effectively exempt from the annual review and approval in the budget process because the benefit qualifications and benefit formulas are specified in law, resulting in an automatic appropriation of benefit payments. In 1962, mandatory spending accounted for just over one-quarter of total Government outlays and discretionary spending accounted for slightly more than two-thirds of Government outlays; the remainder of outlays was for interest. Today, the picture is dramatically different, with mandatory spending having doubled as a share of total outlays, now accounting for 53 percent of all Government spending. Without intervention, entitlement spending over the next four decades will become unsustainable. With the baby boom population beginning to become eligible for Social Security in 2008 and Medicare in 2011, the time to address this problem is now.

The 2008 Budget proposes to place limits on new mandatory spending. In addition to the proposal to address excessive general revenue spending in Medicare, discussed above, the Budget also proposes a pay-as-you-go requirement such that any legislation that increases mandatory spending be offset by reductions in other mandatory spending. Any legislation that increases mandatory spending without an equal offset would be subject to a point of order, or a three-fifths vote in the Senate. If, at the end of a Congressional session, the enacted new mandatory spending legislation increases the deficit, then OMB would be required to make across-the-board cuts to non-exempt mandatory programs to eliminate any increase in the deficit. In addition, the Budget proposes to adopt a new measure to limit legislated expansions in spending for Social Security, Supplemental Security Income, Medicare, Federal civilian and military retirement, and veterans disability compensation. The new measure would be the change in the actuarial unfunded obligations for each of these programs. The Administration is proposing that any legislation that has the effect of increasing the actuarial unfunded obligation for any of these programs be subject to a point of order, or a three-fifths vote in the Senate. Earmarks: Reforms to Ensure Tax Dollars are Spent WiselyAn earmark is a spending provision the Congress inserts in legislation. Frequently, these provisions are not publicly disclosed during the legislative process and often they are special interest projects. A number of organizations track earmarks. The Congressional Research Service (CRS) and Citizens Against Government Waste (CAGW) have been tracking earmarks for over a decade. While they do not use the same definition, their data show similar trends. Earmarks have expanded dramatically in recent years, with the numbers and costs of earmarks more than tripling since the early 1990s. According to CAGW, the Congress added nearly 550 earmarks at a cost of $3 billion to the Budget in 1991. The number of earmarks peaked in 2005. CAGW has estimated that earmarks grew to almost 14 thousand at a cost of $27 billion. CRS data show a similar trend, with earmarks reaching more than 16 thousand in 2005 at a cost of $52 billion. OMB has also been tracking earmarks during recent years and estimates that the number of earmarks grew to over 13 thousand at a cost of nearly $18 billion. OMB is in the process of developing the capability to track earmarks during the legislative process. One major concern about earmarks is the lack of transparency. Most earmarks do not appear in statutory language. Instead, they are included in committee reports that accompany legislation. According to CRS, more than 90 percent of earmarks are in report language. This means that the vast majority of earmarks do not appear in the statutory language that the Congress actually votes on or that the President signs into law. Also, earmarks frequently surface in the late stages of the legislative process, in conference committees between the House and Senate. The President has called on the Congress to fully disclose all earmarks to reduce the amount of wasteful and unnecessary spending. Taxpayers should feel confident that their tax dollars are being spent wisely. Unfortunately, the large number of earmarks and the lack of transparency in the earmarking process make it difficult to assure the public that the Government is spending the people’s money on the Nation’s highest priorities. The President has proposed that the Congress provide justification for earmarks, and identify the sponsor, costs, and recipients of each project. In addition, the President has proposed that the Congress stop the practice of placing earmarks in report language. Finally, he has called on the Congress to cut the number and cost of earmarks by at least 50 percent. Line-Item Veto: A Tool to Reduce Wasteful SpendingThe President is again proposing that the Congress enact a legislative line-item veto to improve the budget process. Forty-three of the Nation’s governors have a line-item veto, authority that permits them to identify and eliminate wasteful and unnecessary spending. From the Nation’s founding, Presidents have exercised the authority not to spend appropriated sums. However, the Congress sought to curtail this authority in 1974 through the Impoundment Control Act, which restricted the President’s authority to decline to spend appropriated sums. The Line-Item Veto Act of 1996 attempted to give the President the authority to cancel spending authority and special interest tax breaks, but the U.S. Supreme Court found that law unconstitutional. The President’s proposal is designed to correct the constitutional flaw in the 1996 Act. The legislative line-item veto would give the President and the Congress an effective tool to eliminate wasteful spending and special interest tax breaks. Under the President’s legislative line-item veto proposal, if the Congress were to pass legislation that includes wasteful spending or targeted tax benefits, the President could send back to the Congress the individual items for an up-or-down vote without amendment under fast-track legislative procedures. If the Congress were to pass the package of line items that the President proposes for cancellation, all savings would be used for deficit reduction and could not be used to augment other spending. Results and Sunset Commissions: Focusing on PerformanceIn his 2008 Budget, the President proposes to create bipartisan Results Commissions and a Sunset Commission. Results Commissions would consider ways to restructure or consolidate programs or agencies where duplication or overlapping jurisdiction has been identified as an obstacle to performance. Proposals from Results Commissions would be reviewed and if approved by the President, transmitted to the Congress to be considered under expedited procedures. The Sunset Commission would consider Presidential proposals to retain, restructure, or terminate agencies and programs according to a schedule set by the Congress. Agencies and programs would automatically terminate according to the schedule unless reauthorized by the Congress. Other Reforms: Increasing Order and Accountability in the Budget ProcessIn addition to the proposals directed at restraining spending and improving Government program and agency performance, the Budget proposes several changes to the budget process that would enhance accountability, improve management, and bring greater order to the budget process. Specifically, the Budget proposes a joint budget resolution, biennial budgeting, and a means to prevent Government shutdowns. The Budget proposes a joint budget resolution that is passed by the Congress and signed by the President. The current budget resolution does not require the President’s signature and, therefore, does not have the force of law. A joint budget resolution would bring the President into the process at an early stage, allowing the President and the Congress to reach agreement on overall fiscal policy before individual tax and spending bills are considered. The Budget proposes biennial budgeting for all Executive Branch agencies, programs, and accounts in which two-year appropriations bills would be enacted in each odd-numbered year. This would permit the Executive Branch to engage in better mid-term and long-term planning, and improve fiscal management. It would also permit the Congress to engage in more extensive oversight.

The Budget proposes to prevent Government shutdowns by allowing

funding to be automatic for those agencies, programs, or accounts

for which an appropriations bill has not been enacted by the start

of the fiscal year. If an appropriations bill has not been enacted,

funding would be automatically provided at the lower of the President’s

Budget or the prior year’s enacted level. This proposal would

prevent Government shutdowns and would prevent the uncertainty and

confusion that arises when the Congress enacts continuing acts or

continuing resolutions. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||