|

Press Release 06-003

Global Warming Can Trigger Extreme Ocean, Climate Changes

Scientists use deep ocean historical records to find an abrupt ocean circulation reversal

January 4, 2006

Newly published research results provide evidence that global climate change may have quickly disrupted ocean processes and lead to drastic shifts in environments around the world.

Although the events described unfolded millions of years ago and spanned thousands of years, the researchers, affiliated with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, say they provide one of the few historical analogs for warming-induced changes in the large-scale sea circulation, and thus may help to illuminate the potential long-term impacts of today's climate warming.

Writing in this week's issue of the journal Nature, scientists Flávia Nunes and Richard Norris explain that they probed a four- to seven-degree warming period that occurred some 55 million years ago during the closing stages of the Paleocene and the beginning of the Eocene eras. The unique data set they constructed, based on the chemical makeup of tiny ancient sea creatures, uncovered for the first time evidence of a monumental reversal in the circulation of deep-ocean patterns around the world. The researchers concluded that it was triggered by the global warming the world experienced at the time.

"The earth is a system that can change very rapidly," said Nunes. "Fifty-five million years ago, when the earth was in a period of global warmth, ocean currents rapidly changed direction and this change did not reverse to original conditions for about 20,000 years."

The global warming of 55 million years ago, known as the Paleocene/Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), emerged in less than 5,000 years, an instantaneous blip on geological time scales. Fossil records indicate that the PETM set in motion a host of important changes around the globe, ranging from a mass extinction of deep-sea bottom-dwelling marine life to key migrations terrestrial mammal species, likely allowed by warm conditions that opened travel routes not possible under previously colder climates. For example, this period is where scientists find the earliest evidence for horses and primates in North America and Europe.

To obtain their data, Nunes and Norris analyzed carbon isotopes--chemical signatures that reveal a host of information--from the shells of single-celled animals called foraminifera, or "forams." Such organisms exist in a variety of marine environments, and their vast numbers per research sample allow scientists to uncover a range of details about the state of the seas.

"A tiny shell from a sea creature living millions of years ago can tell us so much about past ocean conditions," said Nunes. "We know approximately what the temperature was at the bottom of the ocean. We also have a measure of the nutrient content of the water the creature lived in. And, when we have information from several locations, we can infer the direction of ocean currents."

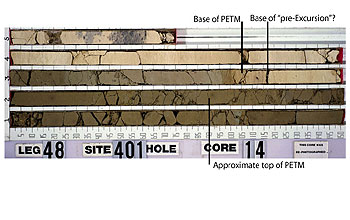

In the study, the scientists looked at a foram named Nuttalides truempyi from 14 sites around the world in deep-sea sediment cores from Deep Sea Drilling Program (DSDP) and Ocean Drilling Program (ODP). The isotopes were used as nutrient "tracers" to reconstruct changes in deep-ocean circulation through the PETM period. Nutrient levels tell the researchers how long a sample has been near or isolated from the sea surface, thus giving them a way to track the age and path of deep-sea water.

The results indicate that deep-ocean circulation in the Southern Hemisphere abruptly stopped the conveyor belt-like process known as "overturning," in which cold and salty water in the depths exchanges with warm water on the surface. Even as it was virtually shutting down in the south, however, overturning apparently became active in the Northern Hemisphere. The researchers believe this shift drove unusually warm water to the deep sea, likely releasing stores of methane gas that led to further global warming and a massive die-off of deep-sea marine life.

Overturning is a fundamental component of the global climate conditions we know today, said Bil Haq, program director in the National Science Foundation (NSF)'s division of ocean sciences, which funded the research. For example, overturning in the modern North Atlantic Ocean is a primary means of drawing heat into the far north Atlantic and keeping temperatures in Europe relatively warmer than conditions in Canada, he said.

Today, "new" deep-water generation does not occur in the Pacific Ocean because of the large amount of freshwater input from the polar regions, which prevents North Pacific waters from becoming dense enough to sink to more than intermediate depths.

In the case of the Paleocene/Eocene, however, deep-water formation was possible in the Pacific Ocean because of global warming-induced changes. The Atlantic Ocean also could have been a significant generator of deep waters during this period.

Modern carbon dioxide input from fossil fuel sources to the earth's surface is approaching the same levels estimated for the PETM period, which raises concerns about future climate and changes in ocean circulation, say the scientists. Thus, they say, the Paleocene/Eocene example suggests that human-produced changes may have lasting effects not only on global climate, but on deep ocean circulation.

"Overturning is very sensitive to surface ocean temperatures and surface ocean salinity," said Norris. "The case described here may be one of the best examples of global warming triggered by the massive release of greenhouse gases. It gives us a perspective on what the long-term impact is likely to be of today's human-caused warming."

-NSF-

Media Contacts

Cheryl Dybas, NSF (703) 292-7734 cdybas@nsf.gov

Mario Aguilera, Scripps Institution of Oceanography (858) 534-3624 maguilera@ucsd.edu

Jon Corsiglia, Joint Oceanographic Institutions, Inc. (202) 787-1644 jcorsiglia@joiscience.org

Nancy Light, IODP-Management International (202) 465-7511 nlight@iodp.org

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent federal agency that

supports fundamental research and education across all fields of science and

engineering, with an annual budget of $6.06 billion. NSF funds reach all 50

states through grants to over 1,900 universities and institutions. Each year,

NSF receives about 45,000 competitive requests for funding, and makes over

11,500 new funding awards. NSF also awards over $400 million in

professional and service contracts yearly.

Get News Updates by Email Get News Updates by Email

Useful NSF Web Sites:

NSF Home Page: http://www.nsf.gov

NSF News: http://www.nsf.gov/news/

For the News Media: http://www.nsf.gov/news/newsroom.jsp

Science and Engineering Statistics: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards Searches: http://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/

|