Fall 2007

Researchers at the Ready to Advance Vaccines

When a Missouri family received a letter in 2001 inviting them to participate in a clinical trial of novel smallpox vaccine at Saint Louis University, the family’s 16-year-old son decided to accept the offer. Like all clinical trial volunteers, he was told before he enrolled not to assume that he would be protected by the vaccines being tested. Still, “It was right after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and they were saying there was a shortage of smallpox vaccine,” recalls the son (as a trial volunteer, his name is confidential). “I figured I might get ahead of the line—just in case.”

With that decision, the teenager became one of 680 volunteers who enrolled in the trial and got vaccinated within three months with smallpox vaccine from the U.S. stockpile. The goal of the trial was to determine if the stockpiled vaccine could be “stretched,” or diluted, to expand the number of individuals the vaccine could protect.

The Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Units (VTEUs)—a national group of NIAID-funded medical research institutions, including Saint Louis University, that conducted the trial—found the vaccine could be diluted up to five times and still retain its potency. That meant the original 15.4 million doses ultimately could protect 77 million people against the unlikely but possible deliberate release of smallpox virus.

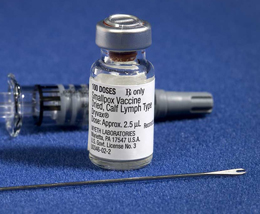

|

| The VTEUs tested diluted smallpox vaccine with the kit shown here, which contains a diluting agent, vial of smallpox vaccine, and bifurcated needle. (Credit: CDC/James Gathany) |

45 Years, Hundreds of Clinical Studies

NIAID established the VTEUs in 1962, more than two decades before the teenager participating in the smallpox trial was born. Since then, the units have worked together to conduct hundreds of clinical trials of investigational vaccines for numerous infectious diseases that affect children, adults, and the elderly. “The VTEUs make it possible in a concerted and organized way to test vaccines that are a national priority,” explains Myron Levine, M.D., D.T.P.H., a long-time principal investigator of the VTEU at the University of Maryland in Baltimore.

The units’ clinicians have tested and advanced vaccines intended to protect infants and young children against devastating diseases such as whooping cough, Haemophilus influenzae infection, and cytomegalovirus infection; to protect against infectious diseases that may be naturally or deliberately introduced into populations, such as smallpox, anthrax, or pandemic influenza; to combat age-old scourges of developing countries, such as malaria and cholera; and to guard against diseases that affect the elderly and other vulnerable populations, such as seasonal influenza and pneumonia.

During the nascent years of the VTEUs, clinicians also tested first-generation antiviral drugs for influenza. “Treatment” remains in the name as a legacy of those early antiviral tests.

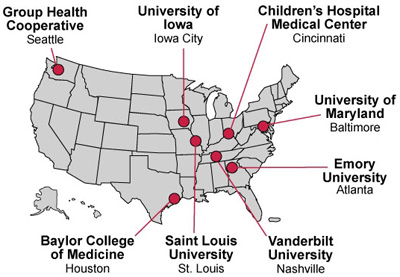

NIAID recently awarded the latest round of VTEU contracts to eight medical research facilities in Atlanta, Baltimore, Cincinnati, Houston, Iowa City, Nashville, Seattle, and St. Louis. According to Carole Heilman, Ph.D., director of NIAID’s Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, all the institutions selected to be VTEUs demonstrate exceptional experience and expertise in vaccine science and great capacity to rapidly recruit volunteers from diverse populations in the community.

NIAID Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Units

|

| NIAID selected eight medical research organizations to receive new VTEU contracts in 2007: Group Health Cooperative, Seattle; University of Iowa, Iowa City; Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati; University of Maryland, Baltimore; Emory University, Atlanta; Vanderbilt University, Nashville; Saint Louis University, St. Louis; Baylor College of Medicin, Houston. (Credit: NIAID) |

Push for a New Pertussis Vaccine

NIAID often directs the VTEUs to conduct important clinical vaccine research that the private sector cannot or will not do. For instance, during the 1980s, widespread controversy surrounded the side effects of the vaccine for whooping cough (pertussis), and vaccination rates for the disease declined. This trend was alarming because pertussis is a highly contagious bacterial disease that can permanently disable and even kill infants. In response, the federal government gave national priority to developing a new pertussis vaccine with fewer side effects.

By 1990, pharmaceutical companies had more than a dozen different candidate pertussis vaccines in development. NIAID wanted to identify the best two vaccine candidates to test in large, definitive efficacy trials. Pinpointing those stellar candidates required a head-to-head comparison of all the pertussis vaccines under development—something no private company would do. Moreover, given the controversy surrounding the safety of pertussis vaccine, it was critical that the data be collected by a neutral, publicly trusted team and be open for public scrutiny. That’s where the VTEUs came into play.

“The credibility and acknowledged expertise of the VTEUs carried the day,” says George Curlin, M.D., M.P.H., who was NIAID’s point person for the pertussis clinical trials and deputy director of the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases at the time. “There was confidence that they would produce information in an unbiased way.”

VTEU clinicians and scientists designed and executed a complex protocol comparing the effectiveness in infants of the 13 candidate acellular vaccines with that of two traditional whole-cell pertussis vaccines. This trial generated the comparative data that helped distinguish the best two acellular vaccines for the next phase of testing. In the end, those two vaccines received FDA approval and came to market. Today they are routinely administered to children without significant adverse side effects.

Gentler than a Needle

The VTEUs also have been an asset for advancing the study of novel vaccine delivery systems. For example, the University of Maryland VTEU conducted the first clinical trial to demonstrate the immunogenicity of an edible vaccine: potatoes genetically engineered to produce Escherichia coli enterotoxin. Six VTEUs played a pivotal role in testing FluMist, a flu vaccine administered as a nasal spray. Although no edible vaccine has reached the U.S. public yet, FluMist has been approved by the FDA since 2003 for healthy adults and children ages 5 through 49. (In September 2007, FDA approved the use of FluMist in children ages 2 to 5 years as well.)

|

| Woman receives a dose of FluMist, the first nasal spray vaccine. The VTEUs generated data critical to FDA approval of FluMist. (Credit: Saint Louis University) |

Today, the VTEUs are in an in-between phase as multiple clinical trials get started under the new 2007 contracts while four studies from the previous round of contracts (awarded in 2002) wrap up. One of the carryover studies is testing a new type of malaria vaccine in 80 volunteers at the VTEU at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Malaria kills at least 1 million people globally every year and sickens more than 500 million, primarily in developing countries. Scientific and financial challenges have historically impeded progress toward a malaria vaccine, so funding the clinical trial of a malaria vaccine through the Baylor VTEU helps overcome a sizeable hurdle.

Unlike other malaria vaccine formulations, the one under evaluation at the Baylor VTEU uses a protein derived from the malaria parasite that has not been tested before in humans. Many vaccines in development have been shown to confer partial protection from infection with the parasite that causes the disease, says Hana El Sahly, M.D., the study’s principal investigator. However, the vaccine she and her colleagues are evaluating is hypothesized to prevent infected individuals from becoming severely ill.

“Just last week, we vaccinated the study participants with their last dose,” adds Shital Patel, M.D., a co-investigator running the clinical trial to determine whether the vaccine is safe in humans, to identify any side effects, and to see if the vaccine elicits the desired immune response in the study participants. The preliminary results of the clinical trial—the first one for this particular vaccine—will become available around the end of 2008. By that time, many clinical trials under the new VTEU contracts will be in full swing.

—Laura Sivitz

back to top