|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

CDER Report to the Nation: 2003 Adobe Acrobat version of this document Drug Review (continued)Index

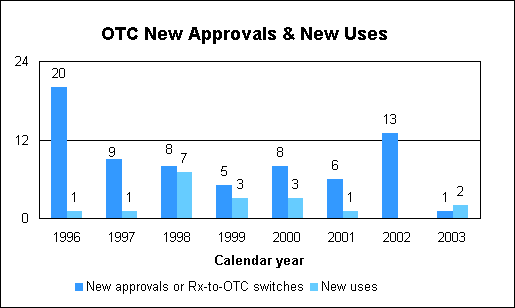

Over the Counter Drug ReviewOver-the-counter drug statistics

We approved one new Rx-to-OTC switch. We approved two supplemental applications for existing OTC products, one of which can be used by children. The approvals are:

Education campaign on safe use of OTCsWe developed a national education campaign to provide advice on the safe use of over-the-counter pain and fever reducers. The campaign focuses on OTC drug products that contain acetaminophen and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, which include products such as aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen sodium and ketoprofen. Many OTC medicines sold for different uses have the same active ingredients. To minimize the risks of an accidental overdose, we are trying to educate consumers to avoid taking multiple medications that contain the same active ingredient at the same time. You can learn more about this educational campaign at our

Web site: Improved labels for OTC medicinesAmerican consumers are benefiting from easy-to-understand labels on drugs they buy without a prescription. A mandatory changeover to the new labels, titled “Drug Facts,” began in 2002. How we regulate OTC drugsWe publish monographs that establish acceptable ingredients, doses, formulations and consumer labeling for OTC drugs. Products that conform to a final monograph may be marketed without prior FDA clearance. Drugs can also be approved for OTC sale through the new drug review process. More information about the OTC drug review process is at http://www.fda.gov/cder/about/smallbiz/OTC.htm. Generic Drug ReviewGeneric drug statistics

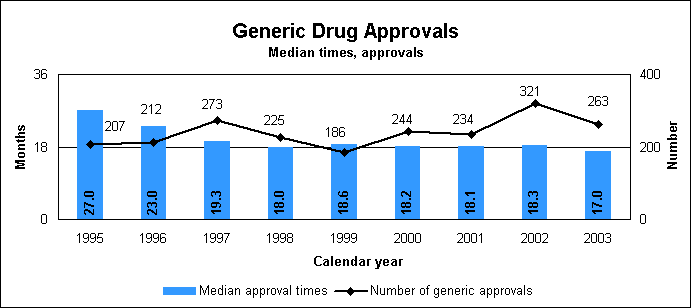

We approved 263 generic drug products in 2003, including a substantial number of products that represent the first time a generic drug was available for the brand-name product. The median approval time for generic drugs was 17 months. The median statistic for total approval time has hovered at about 18 to 19 months for six years. We made changes to decrease the overall time to approval of applications by three months over the next three to five years. We are improving the efficiency of our generic drug review process and increasing the number of chemistry reviewers by one-third. Notable 2003 generic drug approvalsExamples of first-time approvals for the brand-name equivalent drugs are:

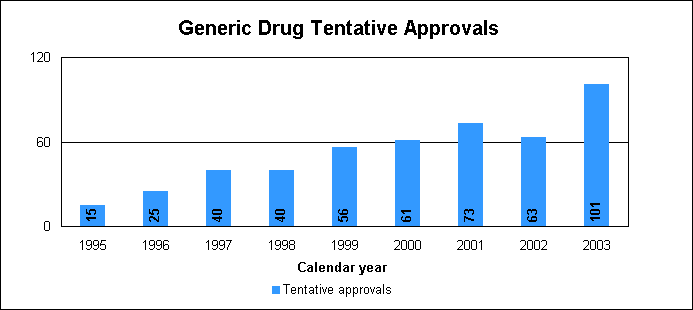

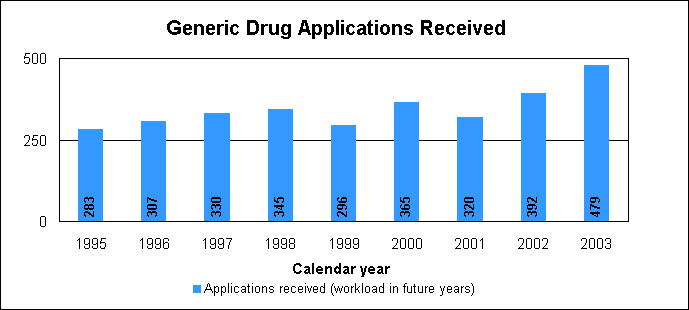

Our approval of generic versions of these drugs last year could save American consumers and the federal government hundreds of millions of dollars each year. Tentative vs. full approvalWe also issued 101 tentative approvals. While full approvals decreased from 321 to 263, the tentative approvals increased from 63 to 101. The review of an application that is tentatively approved requires the same amount of work as a review that results in a full approval. The only difference between a full approval and a tentative approval is that the final approval of these applications is delayed due to existing patent or exclusivity on the innovator drug product. These and other legal issues continue to be a challenge to the generic drug review program. While tentative approvals represent a full workload for us, they are only displayed in the chart on the next page once they are converted to full approvals. For example, some of the 263 approvals in 2003 represent conversions of tentative approvals granted in 2003 or previous years. New law aims to speed approval of genericsProvisions of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003, which became law on Dec. 3, 2003, are expected to decrease time-consuming legal delays in the approval and marketing of generic products. The law incorporates much of the substance of our final regulation issued in 2002, particularly the limitation on 30-month stays that may delay availability of generic drugs. The law codifies several points regarding patent notification and forfeiture of 180-day exclusivity on the part of a generic applicant. We are working on new regulations to implement the law. Generic drug review efficienciesReceipts of generic drug application increased more than one-fifth in 2003 to 479 from 392 in 2002. This dramatic increase in applications makes it imperative that we have the ability to process generic drug applications more efficiently We are continue to look for ways to improve our process and also to provide communication and guidance to industry, with the overall goal of getting generic drug products to the consumer as efficiently as possible. We are taking steps aimed at improving the content and completeness of generic drug applications and assuring that the applications contain the needed information to be evaluated successfully in one cycle. These steps include:

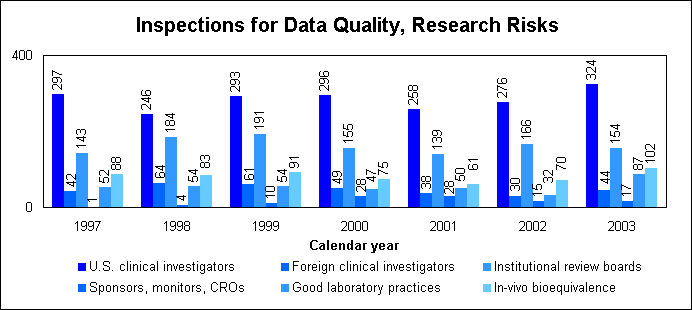

Electronic submissionsThrough public presentations, we are encouraging the generic drug industry to submit their applications electronically. Increased generic drug review staffWe have constituted a third chemistry review division for generic drugs. We are augmenting our clinical review staff to further speed our review of generic drug applications. How we approve generic drugsGenerics are not required to repeat the extensive clinical trials used in the development of the original, brand-name drug. For many products such as tablets and capsules, the generics must show bioequivalence to the brand-name reference listed drug. This means that the generic version must deliver the same amount of active ingredient into a patient’s bloodstream and in the same time as the brand-name reference listed drug. The rate and extent of absorption is called bioavailability. The bioavailability of the generic drug is then compared to that of the brand-name. This comparison is bioequivalence. Brand-name drugs are subject to the same bioequivalency tests as generics when their manufacturers reformulate them. Scientific basis for generic drug reviewWe have continued to articulate the scientific underpinnings of our review process and to work to define mechanisms to evaluate equivalence of certain unique products. Consumer communicationOur efforts to build consumer confidence in generic drug products are continuing through our Generic Drug Quality Awareness program. We have partnered with a number of professional and consumer organizations to launch programs about the quality and benefits of generic drugs. We have helped design messages that appear on prescription bags in CVS and Kmart. We have partnered with Express Scripts to get the word out to their consumers about the quality and value of generic products. Radio public service announcements with the generic drug quality message will be appearing in several geographic areas. Our generic drug public service announcements are at http://www.fda.gov/cder/consumerinfo/generic_info/default.htm. Generic drug Web siteYou can find more information about our generic drug program at http://www.fda.gov/cder/ogd/. Assessing Data Quality, Research RisksInspections for data quality, research risks in 2003We conducted a total of 728 inspections in 2003 compared to 589 in 2002:

When obtaining data about the safety and effectiveness of drugs, sponsors rely on human volunteers to take part in clinical studies and high quality laboratory studies. Protecting volunteers from research risks is a critical responsibility for us and all involved in clinical trials. We perform on-site inspections to protect the rights and welfare of volunteers and verify the quality and integrity of data submitted for our review. We inspect domestic and foreign clinical trial study sites; institutional review boards; sponsors, monitors and organizations conducting research; laboratories that obtain data; and sites performing bioequivalence studies in humans (see “How we approve generic drugs”) and preclinical studies in animals. Our programs to protect volunteers are challenged by increases in the number of clinical trials; the types and complexity of products undergoing testing; and the increased number of trials performed in countries with less experience and limited or no standards for conducting clinical research. Sponsors and clinical investigators protect volunteers by ensuring that:

Special attention is given to protecting vulnerable populations, such as children, the mentally impaired or prisoners. We require sponsors to disclose financial interests of clinical investigators who conduct studies for them. This helps identify potential sources of bias in the design, conduct, reporting and analysis of clinical studies. Top 5 deficiency categories for clinical investigator inspections

International inspections of clinical researchWe have conducted 510 inspections of clinical research in 53 countries from 1980 to 2004. We participate in international efforts to strengthen protections for human volunteers worldwide and encourage clinical investigators to conduct studies according to the highest ethical principles. These efforts include our work with the International Conference on Harmonization and the Declaration of Helsinki. User Fee ProgramAmericans deserve timely access to potentially lifesaving new drugs as soon as possible once they are proven safe and effective. The Prescription Drug User Fee Act of 1992 received its third five-year extension in 2002, known as PDUFA III. This reauthorization will help ensure that we have the expert staff and resources to review applications promptly and get safe, effective new drugs into the hands of the people who need them. PDUFA III maintains the high review performance goals of PDUFA II and includes increased consultations with drug sponsors and provided for earlier feedback on their submissions. Although our resources from PDUFA III are higher than from PDUFA II, our total resources for new drug review have not increased as much as we expected. Under PDUFA II, we collected significantly less in user fees than estimated due to a reduced number of new drug applications and an increased proportion of submissions whose fees were waived. The expectation that the reauthorization would put the user fee program on a sound financial basis has only been partially met. We are concerned about the safety of new medicines following approval. In recent years, 50 percent of all new drugs worldwide have been launched in the United States, and American patients have had access to 78 percent of the world’s new drugs within the first year of their introduction. PDUFA III allows us to spend some user fees to increase surveillance of the safety of medicines during their first two years on the market or three years for potentially dangerous medications. It is during this initial period, when new medicines enter into wide use, that we are best able to identify and counter adverse side effects that did not appear during the clinical trials. Full information on PDUFA III, including the latest performance and procedure goals, is on the Web at http://www.fda.gov/oc/pdufa/PDUFA3.html. User fee performanceUnder legislation authorizing us to collect user fees for drug reviews, we agreed to specific performance goals for the prompt review of submissions. We met or exceeded all our performance goals for the fiscal year 2002 receipt cohort. We are on track for meeting or exceeding all user-fee performance goals for fiscal year 2003. Internet resources for user feesOur user fee Web site has links to more documents and information including our user fee performance report to Congress. The page is at http://www.fda.gov/cder/pdufa/default.htm. End-of-Phase-2A-Meeting PilotMaking better use of data collected early in drug development could help sponsors avoid some pitfalls that lead to either an extra cycle of review or Phase 4 commitments. We are undertaking a pilot program to discuss this early data with drug sponsors voluntarily at an End-of-Phase-2A meeting. We think this will improve dose selection and study design for subsequent clinical trials. More information is available in a concept paper we issued in October 2003 (http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/03/briefing/3998B1_01_Topic%201-Part%20A.pdf). Electronic SubmissionsThe number of new drug applications submitted electronically, the number of participating companies and the number of applications with electronic components continues to grow. The major change last year was the inclusion of two additional types of submissions that can be provided in electronic format: investigational new drug applications and drug master files. Electronic submissions following the electronic Common Technical Document specifications provide our reviewers significant advantages over paper submissions and electronic submissions following past specifications. The eCTD allows our reviewers to build a cumulative table of contents for viewing the entire life cycle of the applications. The CTD and eCTD standardized table of contents puts the same information in the same place every time regardless of application type. This reduces the amount of time reviewers spend trying to find where information is located. It not only improves the efficiency of finding documents but also provides a comprehensive picture of the changes to the application over time. This is particularly useful in the efficient reviewing continuous marketing applications under PDUFA. Last year, we made further strides in establishing standards for the submission of clinical and animal toxicity study data and annotated electrocardiogram waveform data. We cooperation with outside organizations working to publish standards for the submission of study data. These groups include the Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium and the Standard for Exchange of Non-clinical Data consortium working through Health Level Seven. We continue to receive individual case safety reports and other post-marketing reports from manufacturers in electronic format, including adverse event reports. All submissions can use eCTDAs of August 2003, we are able to receive all applications and related submissions in electronic format following the electronic Common Technical Document specifications. This includes:

Internet resources

Antimicrobial ResistanceThe emergence of drug-resistant bacteria is considered to be a major threat to the public health. We developed a regulation outlining new labeling designed to help reduce the development of drug-resistant bacterial strains. This rule became final in February 2003 and aims at reducing the inappropriate prescription of antibiotics to children and adults for common ailments such as ear infections and chronic coughs. Details of our other efforts and resources are at http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/antimicrobial/default.htm. Antimicrobial resistance education campaignLast year, we joined with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to launch an education campaign on antibiotic resistance. The campaign includes print, radio and TV public service announcements and brochures. We are both now working on materials for the Spanish-speaking audience. Pregnancy labelingWe have reviewed the current system of labeling drugs for use by pregnant women and are developing an improved, more comprehensive and clinically meaningful approach. We are consulting with multiple government agencies, medical experts, consumer groups and the pharmaceutical industry to develop this new labeling format. We are working with medical review divisions and pharmaceutical companies to update product labels with available data regarding human pregnancies exposed to drugs during pregnancy. Improving knowledge about use of drugs in pregnancyIn many cases, a disease or condition left untreated may be more harmful to a woman and her fetus or baby than a drug treatment. To improve our knowledge of how drugs work during pregnancy and when women are nursing, we have provided guidance to industry and our reviewers as well as sponsored research.

Research on high blood pressure in pregnancyFDA’s Office of Women’s Health has funded studies to look at specific antihypertensive agents used to treat high blood pressure in pregnancy. Drug Review TeamWe use project teams to perform reviews. Team members apply their individual special technical expertise to review applications:

Advanced scientific educationA committee of our scientists oversees a program of scientific training, seminars, case study rounds and guest lectures. This multidisciplinary program helps keep our scientists up-to-date on the latest developments in their fields and current industry practices. Scientific training for reviewersOur systematic, internal training program is based on core competencies, learning pathways and individual development plans. The program grew from seven activities offered in 1997 to more than 40 in science and science policy. We offer 44 courses in job skills, research tools, leadership and management. Reviewer participants increased six-fold, from about 250 in 1997 to 1,500 currently. Last year, we brought in 40 visiting professors to talk directly to individual review divisions about critical, new drug-related research and techniques. Academics to CDEREach spring, we collaborate with five local universities to present special courses on the most critical needs and interest of our reviewers. Recent topics were:

Date created: May 24, 2004

|