![]()

STATEMENT

BY

DAVID A. KESSLER, M.D.

COMMISSIONER OF FOOD AND DRUGS

FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

BEFORE THE

SUBCOMMITTEE ON AGRICULTURE, RURAL DEVELOPMENT, FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION, AND RELATED AGENCIES

COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS

U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

MARCH 12, 1996

We are fully conscious of the need to provide the best government services for the taxpayers' dollars. It is therefore most satisfying that we can support our request for essentially the same budget as last year with evidence that FDA is providing critical public health protection, and that the agency's performance is continuously improving.

FDA's activities, which ensure the quality of $1 trillion worth of products, are always too numerous to list in our annual budget presentation. Last fiscal year was no exception, and I will only mention a few of its highlights to illustrate the agency's continuing strides to promote and protect the public health.

FDA's Center for Devices and Radiologic Health certified 10,200 mammography facilities from coast to coast, thereby improving the quality of mammography for all women. This program, mandated by the Mammography Quality Standards Act of 1992, was implemented in record time to meet the Congress-specified timetable. By the end of this year, an estimated 185,000 American women will be diagnosed with breast cancer. The new mammography standards and the mandated inspection program now in force will improve the chances that their disease will be detected in early stages, when it can be best treated.

A significant FDA proposal published last year outlined a new patient information program that creates private market incentives to provide useful written information with each filled prescription for drugs. The proposal is designed to increase patients' familiarity with the drugs they use, their potential adverse effects and the importance of the prescribed regimen. Studies have shown that lack of such information significantly contributes to widespread medication misuse that adds an estimated $20 billion to the nation's annual health care bill and causes great losses in productivity.

As part of the Vice President's National Performance Review, FDA last year proposed substantial changes in the way we regulate drugs, medical devices and medications made using biotechnology. The six regulatory proposals to reform the regulation of biologics represent the most significant overhaul of regulation of well-characterized biotech-derived drugs ever attempted by the agency. In essence, FDA proposed to completely harmonize its regulation of such products across the agency.

For most biotech drugs, FDA will eliminate its existing requirement that manufacturing plants be licensed; do away with the existing requirement that test results for each individual lot of biotech drugs be submitted to the agency after the product has been approved by the agency; and the agency will consolidate its 21 different application forms for biotech drugs into one form.

These and the other proposed changes in device and drug regulation will save the companies product development time and tens of millions of dollars, without lowering FDA's high standards of safety and efficiency.

We took a major step to improving the safety of our seafood by issuing the final rule instituting in the industry the so-called HACCP (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points) system, which focuses on preventing problems before they occur and designing safety into the processing of seafood.

Finally, FDA made one of its potentially greatest contributions to the nation's public health by proposing new ways of keeping cigarettes and smokeless tobacco products out of the reach of our teenagers. More than 400,000 Americans die each year of lung cancer, respiratory illnesses, heart disease and other smoking-associated diseases -- more than the combined annual toll of AIDS, alcohol, car accidents, murders, suicides, illegal drugs, and fires. Since smokers almost always become addicted to nicotine in tobacco during their teenage years, our proposal has the potential of sparing this country enormous amount of personal suffering, lost productivity, and medical expenditures.

I could cite many other activities carried out by the agency in its daily work to protect American consumers and promote the public health. But I believe that what puts FDA's performance most clearly in perspective are three recent reports which probe one of the agency's most frequently criticized core functions, the drug review process.

Two of these reports were submitted to Congress. One is the agency's review of last year's progress in implementing the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA), and the other, a General Accounting Office (GAO) study of FDA's drug approvals, was released in October. The third document is FDA's own analysis of the agency's performance in the international arena by comparing the American patients' access to important new drugs with access to such drugs by patients abroad.

Taken together, these three reports profile in depth the invigorating change in the FDA culture actually began some years ago as the agency added modern, efficient management techniques to its traditionally solid scientific base.

This trend is best reflected in the drug review times achieved since the 1992 passage of PDUFA, under which the agency committed itself to very high performance standards. The annual goals rise steeply each succeeding year.

We already have achieved one major 1997 performance goal. We achieved it in fiscal year 1994 -- a full three years ahead of schedule. For the drugs submitted to FDA in fiscal year 1994, we reviewed and acted upon 96 percent of them on time. In most cases, this meant first action occurred within 12 months.

In addition to the new drug applications, PDUFA sets the pace for the agency's review of two types of supplementary applications -- dealing with effectiveness and manufacturing --, for resubmitted applications, and for elimination of backlogs. Rather than reiterating the extensive data from our report to Congress, I can summarize last year's results in all of these categories as being on target or ahead of schedule.

The PDUFA performance targets were established in 1992 in a three-stage process that we regard as a model for reinventing government. First, Congress, government experts, the industry and consumer groups developed a consensus on performance goals. Next, we agreed on the timetable when these goals have to be reached. And last, but equally important, FDA was given the necessary resources to make the program work.

Although greatly assisted by PDUFA, FDA's faster drug reviews cannot be solely credited to the Act. The agency's advance toward shorter approval times started in the late 1980s, when FDA scored significant performance improvements. These early advances are documented in the second report I mentioned. GAO's study of "FDA Drug Approval" tracked the agency's handling of new drug applications (NDAs) submitted from 1987 to the end of 1992, and found solid evidence of progress.

"We found a considerable reduction in approval time..." the report states. "It took an average of 33 months for NDAs [new drug applications] submitted in 1987 to be approved but only 19 months on average to approve NDAs submitted in 1992. Further, the reduction in time was observed for all NDAs and not just for those that had been approved.... [T]he consistency of all our results supports the conclusion that the reduction in time is real...."

GAO also compared the most recently available data on the speed of drug approvals in the United Kingdom and the U.S. The report concluded that while comparisons between the British Medicines Control Agency and FDA are difficult for a variety of reasons,

"the most recent data show that overall approval times are actually somewhat longer in the U.K. than they are in this country."

For us, the GAO comparison of FDA's performance with its British counterpart confirmed a fact which is not widely known and even less acknowledged: the agency leads the world in rapid and efficient review and approval of new drugs.

Evidence of the agency's performance can also be seen in our response to the AIDS epidemic. FDA makes a maximum effort to speed all needed therapies to those who are suffering: in the last four months of 1995, for example, the agency approved 15 drugs for the treatment of cancer. But our progress in approving new breakthrough drugs has been particularly notable in AIDS therapies, all but one of which have been made available in this country well ahead of the rest of the world.

AZT, the world's first effective antiretroviral, was approved here in March, 1987, at about the same time as in France and United Kingdom, and a month ahead of Germany. DDI, the second antiretroviral, received FDA's approval seven months ahead of France, ten months ahead of Germany, and 28 months ahead of the U.K. DDC was allowed on the American market a year and a half ahead of France and Germany, and 27 months ahead of the U.K.

D4T, the fourth drug against AIDS, was approved in France, Germany and the United Kingdom in January of this year. In the U.S., it was approved in June 1994. 3TC, which FDA approved in November 1995, is yet to be approved elsewhere. Saquinavir and ritonavir, the two antivirals that FDA approved since last December, are also awaiting foreign approvals. The review of saquinavir took 97 days, and ritonavir was approved in just 72 days, a new record for the AIDS therapies. Both products are protease inhibitors, the first new class of AIDS drugs since AZT.

Other important drugs that FDA approved well ahead of its counterpart agencies included taxol for ovarian cancer, fludarabine for chronic lymphocytic leukemia, dornase alpha, also called DNAse or Pulmozyme, for cystic fibrosis, Betaseron for multiple sclerosis, and riluzole for Lou Gehrig's disease.

To more fully evaluate FDA's worldwide standing, we last year performed a study comparing the availability of new drugs here and in England, Germany and Japan, the countries which together with the U.S. account for 60 percent of global pharmaceutical sales.

Our analysis focused on 185 new drugs -- out of the worldwide total of 214 -- that were launched in at least one of the four surveyed countries between January 1990 and December 1994, the most recent five-year period for which we could get the data.

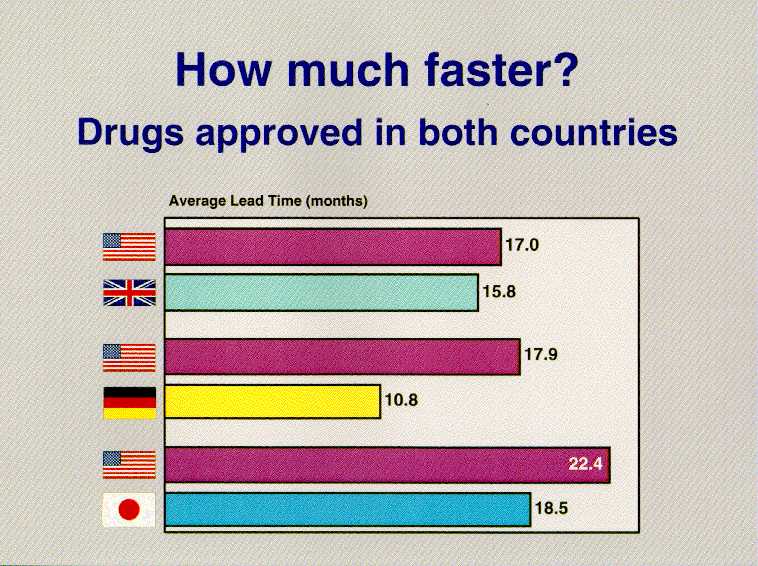

Once the data base was assembled, we asked a number of questions: First, we wanted a two-country comparison between the U.S. and each of the other three countries to see, comparatively, when drugs were approved. In every case, for the time period studied, the U.S. was the first to approve more of the drugs that eventually became available in both countries.

Of the 58 drugs that were approved both here and in the U.K., 30 were approved first in the U.S. The U.K. was ahead of us in approving the remaining 28. But if our edge over the U.K. was only slight, the disparity between us and the other two countries was much bigger. We were first in approving 31 of the 44 drugs approved both in the U.S. and Germany, and we were ahead of the Japanese in allowing marketing of 10 of the 14 compounds eventually used in both countries.

When we looked at the comparison of when these drugs became available to patients, there were other surprises. Of the 30 drugs that reached our market ahead of the U.K., we were faster than the British by an average of 17 months. Of the 28 drugs that the U.K. sent to market first, their average lead was not quite 16 months. In comparison with Germany, we get drugs that both countries approve to the market about 18 months faster -- on average -- than the Germans when we market the drug first. They get to market on average of 11 months faster than us when they approve it first.

When a drug is approved in both the U.S. and Japan, the U.S. gets it to market on the average nearly two years before the Japanese. When they approved a drug first, they did so by an average of about 19 months.

But what about the drugs that have been approved in those other countries, but not approved in the U.S.? Do European and Asian citizens have important pharmaceuticals available to them that are not available in America? And if so, are these drugs clinically significant?

Of all the therapeutics from these 214 on the market worldwide that we have not approved, only a small handful could be considered important molecular entities -- i.e., drugs that offer at least a modest therapeutic advance over existing products, or can be used to treat conditions for which no therapy now exists. Everything else is a standard drug with an essentially equivalent product already on the American market.

Here is what we found: In England, there are 29 drugs from this (((therapeutically important?))) group that are not approved in America. Conversely, we have 18 drugs on the market that they do not.

When we studied the list of drugs they had but we did not, we found two that we thought might be priority drugs. One was remoxipride, which appeared to be a promising new treatment for schizophrenia. The English approved it, but as more and more patients took the drug, it was found that in some of them it caused the bone marrow to shut down, causing aplastic anemia, a life-threatening disease.

The other drug was centoxin, a biotech product of an American company to treat sepsis caused by gram negative bacteria. It was also approved in the U.K., while FDA did not find that the submitted data demonstrated safety and efficacy. We asked the company to carry out another study which eventually showed that the drug did not work, and that it might actually increase the risk of patient death.

Both of these drugs have been taken off the world market.

There is one other set of international data that bears on an issue of current interest. As the agency's review and approval times have grown shorter, we have heard increasingly frequent claims that the overall time to develop a drug has grown longer. If true, this would be a disturbing trend.

FDA has not been able to conduct its own study of overall drug development times, but there is some information in the literature that does not support these statements. According to a recent study by the Centre for Medicines Research, a private organization that works closely with the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry, there has been no real change in drug development times since 1980. The Center checked the development time of 700 drugs in 20 countries -- including the U.S. -- and found that between 1980 and 1994, the mean development time varied between 10 and 12 years. In 1994, it was 11.5 years.

Drug development time before an application is submitted to FDA is influenced by factors that in most cases are not under the control of the agency. To such extent as the agency can facilitate the process by clarifying to sponsors what studies are needed to win rapid approval for their products, we are committed to do so. When it comes to potentially unique life-saving drugs, FDA time and again takes the initiative to work hand in hand with the drug developers to expedite the approval process. Fast access to new drugs and devices ranks at the very top of the concerns of the agency.

Important as they are, drug approvals are only one of many concerns of FDA, whose responsibilities include thousands of products of importance to the public health.

The agency has also made improvements in the times for the review and approval of medical devices. With respect to the so-called 510(k) process, through which 98 percent of all medical devices evaluated by FDA reach the market, the average review time in fiscal year 1995 was 137 days, down 24 percent from the 184-day average in fiscal year 1994. The average review time for those devices needing premarket applications (PMAs) is still too long, but we are making progress there as well. The average PMA review time in fiscal year 1995 was 20 months.

It is important to remember, however, where the Agency was in the 1980s. Congress found -- as did FDA -- that the scientific and medical standards for the review of medical devices were lacking. FDA looked at devices the way an engineer would, and we failed to focus sufficient attention on whether the device would actually make the patient better. Congress told us to do better, and we have. The clinical standards for medical device reviews have been bolstered significantly, and now we are hard at work on reducing the review times.

We are making similar efforts to increase the timeliness and predictability of our action on food and color additive petitions. First, in order to address the backlog of pending petitions, we have allocated additional resources to the program: 23 additional agency scientists have been reassigned temporarily to the food additive program; the agency is awarding contracts for expert review of certain portions of food additive data packages; and one and one-half million dollars have been spent on enhanced computing facilities for the program. With these efforts we will begin to see a decrease in the petition inventory.

In addition to these added resources, we instituted a threshold of regulation policy under which indirect food additives that do not present any substantial safety concerns are exempted from the petition process. The agency processed 47 submissions under this new policy in 1995.

This review of FDA's performance would be incomplete without at least a brief reference to the many activities undertaken in pursuit of our mandate as a science-based consumer protection agency. FDA investigators were involved last year in hundreds of cases involving the manufacture, imports or distribution of dangerous or potentially hazardous products.

One example of their activities involved a Massachusetts shrimp company which was adulterating its products with three chemicals: it used saccharine to overcome an undesirable taste, sodium hydroxide to alter the color, and sodium tripolyphosphate to increase the yield. The president of the company was convicted on 101 counts and sentenced to three years in prison, to be followed by two years of supervised release.

Another important consumer protection action, carried out in cooperation with the U.S. Customs Service and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, halted the smuggling into the U.S. of large quantities of clenbuterol and other unapproved drugs that were then mixed in feed sold to veal producers throughout the Midwest. Clenbuterol is used in some countries to increase muscle in animals, but traces of the drug in meat products have caused outbreaks of food poisoning in France and Spain. FDA discovered that the drug was reaching this country when it appeared in animals shown in agricultural competitions. The indicted Wisconsin feed distributor is awaiting sentencing.

Finally, FDA's criminal investigators continue to play a leading role in shielding the public against dangerous product tampering. A recent case which they helped to swiftly resolve in cooperation with FBI involved the tampering of a baby formula and an attempted blackmail. The suspect was apprehended before his scheme caused any bodily harm, and has been indicted by a federal grand jury.

All of our activities follow the two principles that have traditionally guided Congress and FDA in setting regulatory policies: products that are important for the public health must be safe and effective. If a drug or a medical device is not safe, it should not be approved or allowed to harm consumers. If it does not work, it is of no value to the public, and has no justification in the market place.

These principles are a proven success. They have made FDA's rigorous product evaluation a lasting and effective shield for the nation's public health, and have helped make American therapies and devices sought-after throughout the world.

We are determined to maintain those standards, Mr. Chairman. We will be fast -- and keep on working at getting faster -- while continuing to protect the public health. The principles of safety and effectiveness, speed and caution are not at cross purposes: they work in harmony for the benefit of the American consumer, whose health is our most important achievement.

Turning to FDA's FY '97 budget request, the Administration's budget includes a total FDA request of $1,024.2 million. This consists of $878.4 million in budget authority, $106.3 million in authorized user fees and $39.5 million for two new user fees proposed for legislation. The budget authority is maintained at the FY '96 level. The user fees reflect modest increases in existing user fees and the two new proposed additive user fees, for Medical Devices and Imports. Without an increase in non user fee areas, FDA is absorbing cost increases necessary for the agency to carry out its primary mission. The highlights of our FY '97 request are as follows:

FDA proposes a series of Food Safety initiatives to address current concerns and to meet the safety issues we are likely to encounter as we enter the 21st century. The initiatives include expedited implementation of the new Seafood HACCP regulation ($1.2 million); Federal and state partnerships to enhance food safety ($1.2 million); and new approaches for the review of food additive petitions ($1.4 million). For FY 1997, FDA is applying a $3.8 million increase to its operating base to cover the anticipated FY 1997 cost of these initiatives.

The FY 1997 budget request for Buildings and Facilities of $8.4 million is $3.8 million below the FY 1996 level. The requested $8.4 million will enable the Agency to maintain its many facilities nationwide by addressing only our most urgent repair and improvement requirements.

In FY 1997, federal and state personnel will inspect 10,000 mammography facilities and conduct 3,000 facility certifications. To meet the costs of the program, FDA requests an increase in MQSA authorized inspection user fees of $0.4 million for a total of $13.4 million and 35 FTEs.

FDA requests an increase of $2.8 million in FY '97 and estimates total user fees of $87.5 million and 700 FTE to implement PDUFA in FY '97. As envisioned in the Act, this level of support will enable the Agency to diminish significantly the time necessary to review new prescription drug and biological product license applications. In FY '97, 90 percent of filed New Drug Applications (NDA) and Product License Applications /Establishment License Applications (PLA/ELA) submissions are to be reviewed within 12 months.

In addition to the existing user fees, FDA will be seeking separate legislative approval of the following additive user fees:

FDA is requesting $24.5 million in additive user fees, to be collected from the medical device industry. These application fees will enable the agency to promptly review device applications. If user fee legislation is adopted, we have committed to making decisions on 510(k) applications within 90 days. Ninety-nine percent of all premarket applications are filed under section 510(k). We have also committed, in connection with user fee legislation, to review the more complicated PMA applications within 180 days.

For FY '97 the user fee goal is to increase the percentage of 510(k) applications completed within 90 days from 50 percent in FY '95 to 90 percent, and to increase the percentage of first review cycles for PMAs completed within 180 days from 45 percent in FY '95 to 75 percent. The proposed user fees will also help to increase industry guidance, strengthen postmarket monitoring, improve the Agency's ability to assess public health risks, and upgrade automation capabilities and integrate program information systems.

FDA is proposing to collect $15.0 million in additive import user fees to fund the Operational and Administrative System for Import Support (OASIS). The system is expected to enable the agency to substantially reduce the risk of potentially harmful foods and other imported products reaching the American market place. The importer/broker community benefits through faster turn-around times, elimination of large volumes of paperwork, and reduced costs of doing business. OASIS will give FDA staff access to historical information to better target high risk products and firms, the ability to plan inspections more effectively, and the ability to share findings from inspection and lab analyses with other offices.

(Hypertext updated by jch 1999-JUL-16)