![]()

STATEMENT BY

DAVID A. KESSLER, M.D.

COMMISSIONER

FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

BEFORE THE

COMMITTEE ON LABOR AND HUMAN RESOURCES

UNITED STATES SENATE

FEBRUARY 21, 1996

As we explore that question, it is important to acknowledge that we share the same goals. I know, Senator Kassebaum, that you and members of the Senate Labor Committee understand that American patients are best served when they are assured that the medicines they take are safe and really work, that American patients are most helped when they are assured that medical devices are safe and really work. The rigorous demand for safety and efficacy that makes FDA approval the international gold standard is, in fact, in the best interests of American patients. Likewise, FDA shares with you the belief that timely access to new drugs and devices that are shown to be safe and effective is an important measure of how well the Agency protects and promotes public health in the United States.

If we are to achieve our shared goals of improving the Agency's ability to protect and promote the public health, we must base our work on FDA's current performance. Unfortunately, too many of our critics justify the call for "reform" based on how the FDA did its job in the 1980s or earlier. They have missed the substantial progress that the dedicated doctors, nurses, engineers, chemists, microbiologists, biostatisticians, nutritionists and others at the FDA have achieved over the past several years. They would have us ignore the important lessons we have learned about the kind of change that will result in getting safe and effective drugs and devices to the market more quickly. Those who fail to recognize the Agency's performance and achievements threaten -- intentionally or not -- to undermine the real progress the Agency has made. Undermining progress in critical public health and consumer protection is not "reform."

MEETING AND EXCEEDING THE PRESCRIPTION DRUG USER FEE PERFORMANCE GOALS

According to the General Accounting Office (GAO), the average approval time for new drug applications (NDA) submitted to the Agency in 1987 was 33 months. For NDAs submitted in 1992 the time had been reduced to 19 months. These improved approval times have been made possible by shortening the time for completion of most first reviews to only 12 months. How did we do it? Congress, the Agency, and the pharmaceutical industry recognized that additional resources were one key to improving FDA's review of drugs and biologicals, and Congress enacted the Prescription Drugs User Fee Act of 1992 (PDUFA). The Agency, in turn, committed to very aggressive performance standards, with higher hurdles in each succeeding year until full implementation in fiscal year 1997. These performance standards were negotiated with and agreed to by the pharmaceutical and biotech industries.

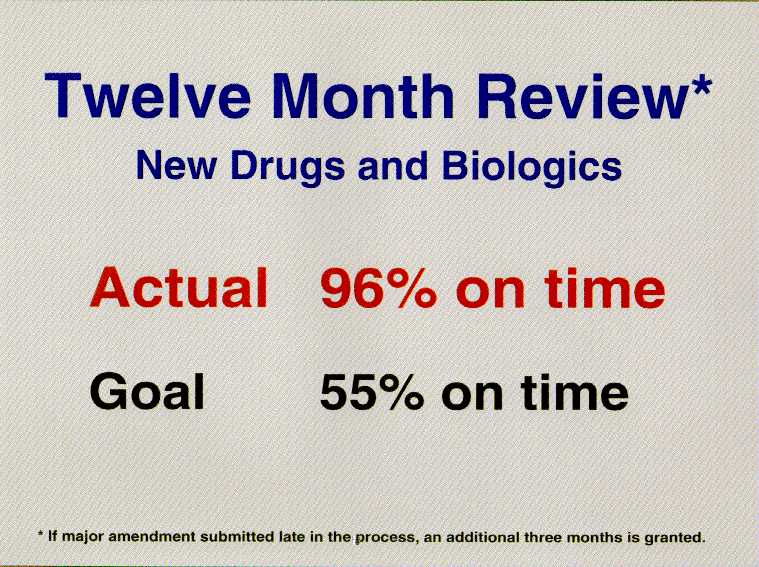

We already have achieved one of the major 1997 performance goals.

We achieved it in fiscal year 1994 -- a full three years ahead of

schedule. For the drugs submitted to FDA in fiscal year 1994, we

reviewed and acted upon 96 percent of them on time. In most

cases, that meant first action within 12

months.

This improved performance has been validated by GAO. At the request of this Committee, GAO looked at how FDA was performing even before PDUFA was enacted. GAO found that review and approval times for new drugs have been reduced dramatically. In addition GAO found that by 1994, FDA review and approval times were faster than those in the United Kingdom -- a country many critics like to cite as a way of doing things better and faster.

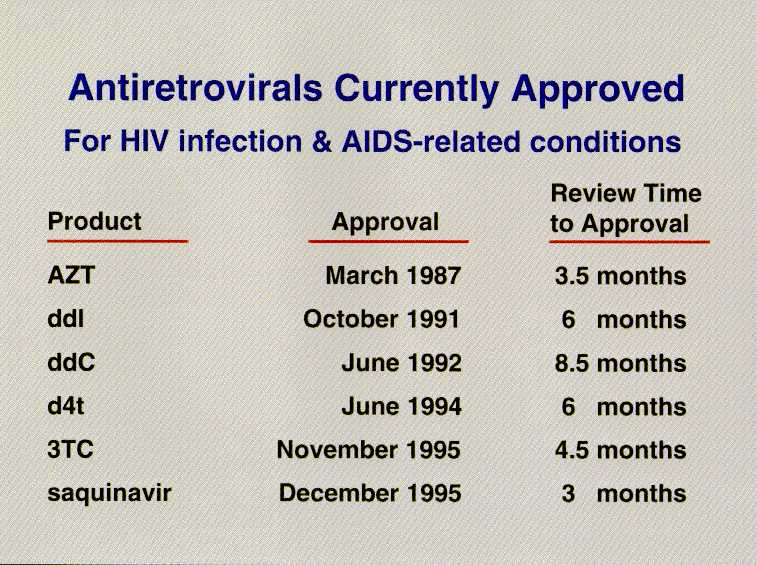

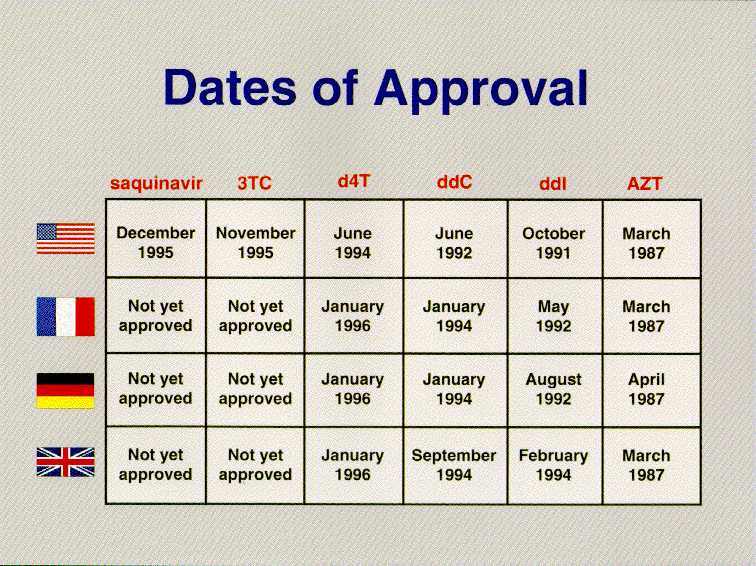

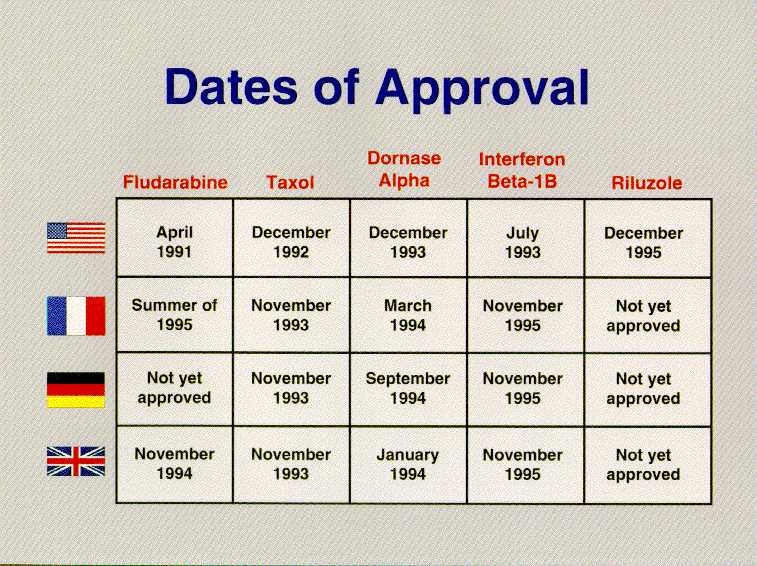

We should never forget that the ultimate goal is ensuring American patients have access to world-class medicines. By that measure as well, the FDA is delivering. The story of AIDS therapies is especially telling. Of the six antivirals used to treat AIDS, FDA was first to approve them in five instances, DDI, DDC, D4T, 3TC and Saquinivar. In the case of AZT, FDA acted contemporaneously with France and the United Kingdom. Two of the newest and most promising AIDS therapies will be considered at an FDA advisory committee next week, and we will be the first country to do so. But the story goes beyond AIDS. Taxol for ovarian cancer, Fludarabine for lymphocytic leukemia, Pulmozyme for cystic fibrosis, Betaseron for multiple sclerosis, Riluzole for Lou Gehrig's disease, and Cognex for Alzheimer's were all first approved in the United States.

One measure of FDA's drug review performance is found in how we compare to the performance of other major regulatory agencies around the world. We looked at the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan and found we compare very well. First, there are numerous drugs with important therapeutic values available here but not in these other countries. Second, virtually all of the drugs available in these other countries but not approved here have therapeutic equivalents in the United States. Third, the United States is first to approve a significant proportion of "global" drugs -- those ultimately approved by more than one country. Finally, we have a strong safety record.

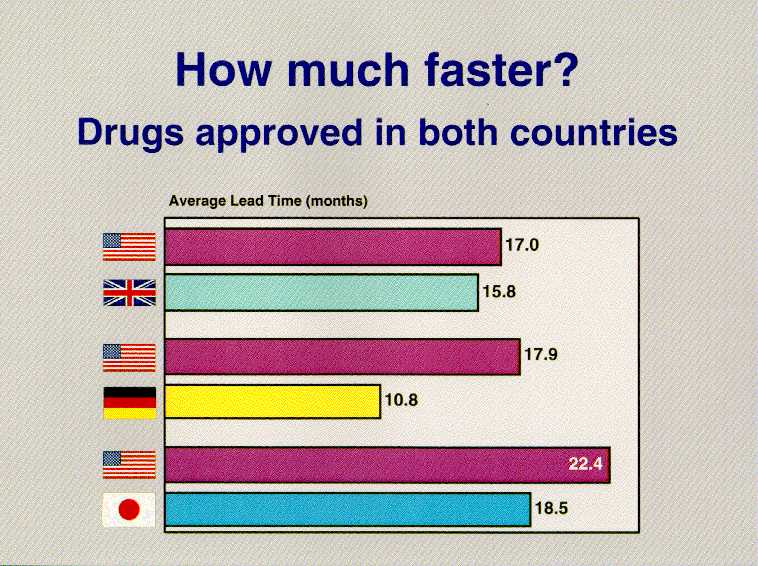

These conclusions are based on our analysis of the "new molecular entities" (NMEs) introduced anywhere in the world between 1990 and 1994. We looked at when those drugs were approved here and in Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom -- four countries that account for 60 percent of global pharmaceutical sales. Let me just give you a brief glimpse at the numbers in the FDA study, "Timely Access to New Drugs in the 1990s: An International Comparison." There were 58 drugs that had been approved in both the United States and the United Kingdom. We approved 30 of them first, the United Kingdom 28. When we approved a drug first, we did so by an average of 17 months before the United Kingdom; if they approved first, they were ahead by an average of 15.8 months. There were 44 new drugs approved in both the United States and Germany. We approved 31 of them first, Germany 13. When we approved a drug first, we did so by an average of 17.9 months before Germany; if they approved first, they were ahead by an average of 10.8 months. There were 14 new drugs approved in both the United States and Japan. We approved 10 of them first, Japan 4. When we approved a drug first, we did so by an average of 22.4 months before Japan; if they approved first, they were ahead by an average of 18.5 months. If you are an American patient, you have access to therapeutically important new drugs sooner than any other country's citizens.

In addition to shortening review times, the Agency has developed a number of innovative and well accepted mechanisms that give seriously ill and dying patients access to potential therapies before they are approved for marketing. We recognize that this approach has its risks. But we also recognize that when it comes to getting needed therapies to terminally ill patients, the riskiest thing we can do is to be unwilling to take risks.

We have instituted innovative pre-approval policies, such as the "treatment IND," under which patients may get access to a promising drug after clinical testing shows that it may be effective, but before it is approved for marketing. We also have developed a process to accelerate approval of drugs for serious and life-threatening diseases, by approving such drugs for marketing before the data from traditional clinical trials are complete, if the drug shows an effect on a "surrogate marker." A surrogate marker is a laboratory measurement, such as an increase in the number of CD4 cells in a person with HIV, that is used to predict actual clinical outcome, such as longer life.

Improvements also have been made in the times for the review and approval of medical devices. With respect to the so-called 510(k) process, through which 98 percent of all medical devices evaluated by FDA reach the market, the average review time in fiscal year 1995 was 137 days, down 24 percent from the 184-day average in fiscal year 1994. The average review time for those devices needing premarket applications (PMAs) is still too long, but we are making progress there as well. The average PMA review time in fiscal year 1995 was 20 months.

It is important to remember, however, where the Agency was in the 1980s. Congress found -- as did the Agency itself -- that the scientific and medical standards for the review of medical devices were lacking. FDA looked at devices the way an engineer would; we did not focus sufficient attention on whether the device would actually make the patient better. Congress told us to do better, and we have. The clinical standards for medical device reviews have been bolstered significantly, and now we are hard at work on reducing the review times.

Although most of the discussion of FDA reform focuses on the human drug and device review processes, the Agency also has significant responsibility for the review and approval of animal drugs and food and color additives. The American food supply is one of the safest in the world. The premarket determinations that animal drugs are safe and effective, especially when they are intended for use in food producing animals, and that food additives and color additives are safe constitute critical links in the food safety chain.

As is the case with human drugs and devices, the Agency has recognized the need to improve the timeliness of the product review processes in both these areas. In the new animal drug area, approval times that had steadily increased between 1988 and 1994 have begun to decline. This is particularly significant given the changing nature of the types of applications being submitted to the Agency. Five years ago, a large part of the applications were for combination feed drugs. These consist of two or more drugs already approved for specific indications and species. Today, we are receiving many more applications for new chemical entities, new species or new applications. As a result, the complexity of the applications has increased considerably.

The Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) has developed procedures to facilitate the development of better applications and to expedite the review process. Through pre-Investigational New Animal Drug exemption conferences and phased submission of the technical sections of the New Animal Drug Application, CVM has reengineered the review process to decrease approval times and increase the availability of safe and effective animal drugs.

Similarly, the Center for Food Safety and Nutrition has developed a plan to increase the timeliness and predictability of Agency action on food and color additive petitions. First, in order to address the backlog of pending petitions, the agency has allocated additional resources to the program: 23 additional Agency scientists have been reassigned temporarily to the food additive program; the Agency is awarding contracts for expert review of certain portions of food additive data packages; and one and one-half million dollars have been spent on enhanced computing facilities for the program. With these efforts we will begin to see a decrease in the petition inventory.

In addition to these added resources, we instituted a threshold of regulation policy under which indirect food additives that do not present any substantial safety concerns are exempted from the petition process. The Agency processed 47 submissions under this new policy in 1995.

Here again, we recognize that one way to decrease review times is to improve the quality of the food additive petitions that are filed with the Agency. We have been working with the industry to do that. FDA personnel have begun conducting workshops for petitioners to discuss what data are needed to file a complete food additive petition.

Food additives are distinctly different than drugs and devices. Whereas drugs and devices provide therapeutic benefits to certain individuals, food additives will potentially be consumed by everyone in the population. Whereas drug and device approvals are product specific, a food additive approval results in a regulation permitting anyone to manufacture or use the additive, consistent with any patent protection and in conformance with the limitations of the regulation. These facts contribute to the unique safety concerns relating to food additives and the unique features of the review process of food additives. We welcome the opportunity to discuss this process further at another time.

We have improved review times without sacrificing the high standards that give Americans confidence that their drugs are safe and work. Under PDUFA, the Agency was assured of adequate resources to do the job and the job was clearly defined through performance goals. At the same time, how to achieve those goals was left to Agency management, and accountability to Congress was assured through the five year authorization. That was real reform. Reauthorization of this program should be a cornerstone on which we build other improvements.

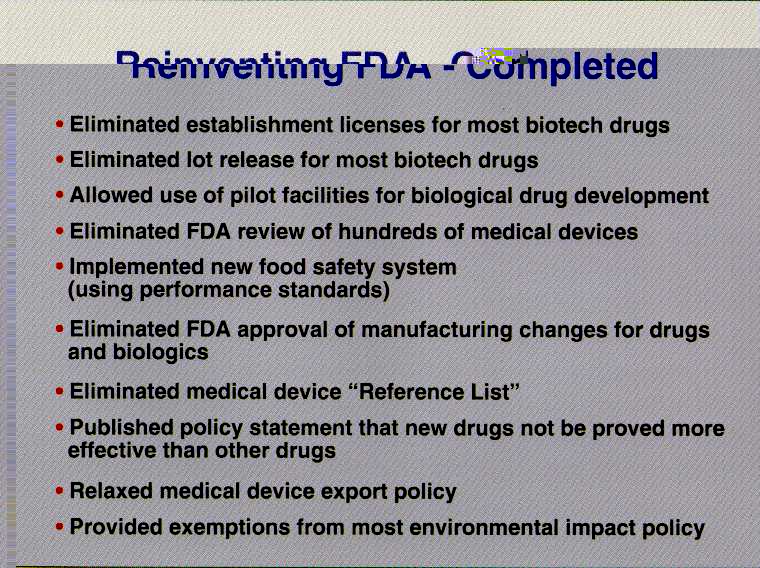

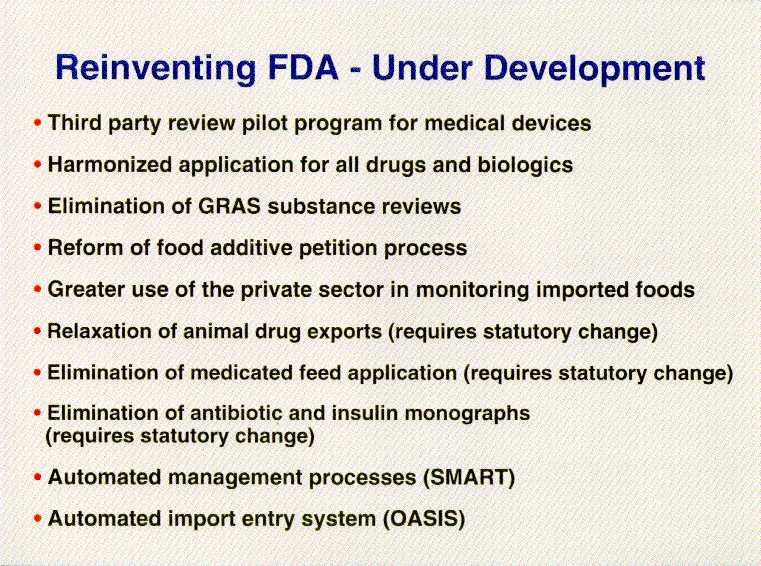

The progress we have made, however, is the result of much more than the additional resources available under PDUFA and extends beyond the drug review process. Of equal significance has been the commitment of Agency management to streamline and improve the way we regulate. I think we all can agree that strong consistent management, the removal of unnecessary regulatory burdens, and the elimination of wasteful or inefficient practices all serve the critical public health goals to which we are committed. A review of the Agency's contribution to the Administration's Reinventing Government Initiative well demonstrates the depth of our commitment to improving our regulatory processes. For example, we have changed the way we regulate biotechnology products, instituted management reforms ranging from team review to greater use of outside expertise, eliminated or modified product and process reviews where the public health risks did not justify the allocation of resources devoted to those tasks, simplified and expedited the export process, engaged industry in a constructive dialogue about how to do more. We are committed to doing more, and we welcome the opportunity to work with you, Senator Kassebaum, and the Committee, and to continue working with the industry, on further improvements.

We appreciate having the opportunity to discuss the "Food and Drug Administration Performance and Accountability Act of 1995," S. 1477, and the impact this bill would have on the Agency's ability to protect and promote the public health. I would like to acknowledge and commend the Chairman for her leadership on these issues. We look forward to working with you and the other members of the Committee on these important issues.

There are many sections of S. 1477 which we believe could be the basis for constructive improvements, and on which we hope to be able to continue to work with the Committee in developing strong legislative improvements. These provisions include a statement of Agency mission, specification of performance standards, changes to the export requirements, contracting-out authority, establishment of adequate reporting systems to enhance Agency accountability and the need for greater input into the guidance documents that we issue.

The general thrust of this legislation is, I believe, how the Agency can do its job better, more efficiently. We share the Chairman's concern with these issues. We heeded and acted upon the concerns you and others -- Senator Kennedy, Senator Mikulski, Senator Frist -- expressed at the hearing last April. We recognized and have addressed many areas that needed improvement. We recognize there is more to do.

As the Committee has requested, we are going to address in some detail the product review process, and whether it would be feasible to meet the review times set forth in S. 1477 without compromising our existing standards of safety and effectiveness and without additional resources. Our testimony will focus on the drug review process, although the comments generally are applicable to the other product reviews for which we are responsible. We will then address the other provisions in the bill, except for those dealing with promotion of off-label uses (Section 407), which will be discussed separately in Mr. Schultz's testimony tomorrow.

We must remember that today's drugs, and science, are not what they were a few decades ago. It may look as though what a company is doing now -- showing that a drug is safe and effective -- is the same thing it was doing decades ago. But that is not the case. What the public, the scientific community and regulators around the world expect is very different now. Until just a few decades ago, clinical drug testing was largely an ad hoc anecdotal observational art -- patients received a drug and clinicians assessed whether individual patients were helped or harmed. In recent decades, indeed in recent years, a great deal of data and understanding have accumulated regarding many aspects of clinical development, including placebo effect, multiplicity of endpoints, post hoc analyses, surrogate endpoints, sources of investigator bias, subset analyses, effects of demographic factors (gender, age, race), drug interactions and impact of concomitant therapies. With these understandings has come a realization that both the observational approach and clinical trials which are not carefully designed, while they may correctly identify treatments whose benefits are dramatic and adverse effects are highly limited, often give incorrect impressions regarding a treatments' safety and efficacy. Thus, the old approaches often led to countless incorrect practice decisions (e.g., unnecessary appendectomy and hysterectomy, use of antibiotics for the common cold, for example.)

Moreover, there are new technologies with which we must now learn how to deal with -- xenotransplantation, transgenic animals, devices that hold biological systems inside of them, robotics, neural networks, computer guided surgery, gene therapy, and neucleic acid vaccines to name a few. We need to develop scientifically-sound ways to both protect and promote the public health in areas of explosive growth and uncertain science.

Every application submitted to the Agency purports to demonstrate that a drug is safe and effective for treatment of a specified ailment or condition. Upon independent review, however, many applications do not support an objective finding that the drug, in fact, is safe and works. The Agency's job is to conduct that independent review. The basis for the Agency's decision is the data collected by the sponsor during pre-clinical and clinical testing. We have to determine that the studies are well designed and capable of demonstrating safety and effectiveness. We also have to determine that the data on which we make our decision have integrity: that the trials actually were conducted and done so consistent with the protocols, the primary data accurately reflect the actual clinical results, and the company's analyses of the data are fair and objective. The various components of a typical drug application -- chemistry, toxicology, biopharmaceuticals, etc., -- and the types of questions that need to be answered in determining whether a drug is safe and effective are outlined in Attachment 1.

For each medical product, there must, on balance, be demonstrable net benefits that are greater than the risks. Few, if any, new products are totally safe; so judging their safety becomes a risk-benefit decision. We must determine if each new drug or device is safe enough in view of its anticipated benefits and the comparative benefit of other available treatments. The benefits of a life-saving drug or device, where there are limited treatment options, might justify its marketing despite known risks, even when the risks involve serious injury or death. This is often the case with drug therapies for cancer. On the other hand, for lesser benefits, the risk patients are willing to accept from a drug or device goes down commensurately.

The availability for review by the Agency of the primary data on which the sponsor bases its claims of safety and efficacy is critical to the drug review process. I would like to commend the Chairman for recognizing this in her bill. Why is it not sufficient for the Agency to rely on summary data? Experience repeatedly has demonstrated that review of primary data is critical to verify, inter alia, the following: that responses of tumor and infections were correctly catagorized and were truly due to the study drug; that judgmental endpoints are supported by objective data and not subjected to bias; and, that adverse events are correctly categorized as to severity and causality by the drug. Additionally, access to primary data improves both the quality and speed of the analysis by permitting the reviewer to confirm that each analysis included only and all appropriate subjects, perform critical analyses to determine to relationship of drug effects to age, gender, race, disease stage, concomitant therapies, and other key factors, and assess the impact of the drug on parameters that may not have been summarized by the sponsor. Thus, provision of primary data not only allows verification, it facilitates better and faster analyses of the safety and effectiveness of the drug.

Many different types of problems have been identified in the review process. For example, has the sponsor asked the right questions during drug development? A case in point involved the development of certain drugs to treat heart failure (phosphodiesterase inhibitors), when concern arose about potential adverse effects on survival. Studies were therefore conducted to examine both the symptoms of heart failure and the impact on survival. Unfortunately, it was discovered that although the drugs improved the symptoms of heart failure, they significantly decreased survival. As a result, the sponsors did not pursue approval of these drugs.

Another example of the types of problems that have been identified through the Agency's review of drug applications is found with a product known as Multishield Topical Lotion. According to the manufacturer, this lotion was supposed to be effective in preventing skin absorption of mustard gas. It was proposed for use by American troops in Desert Storm.

When FDA raised questions about the Multishield IND, our laboratories attempted to test Multishield, using the methodology the drug's manufacturer provided to us that purportedly showed the product met its IND specifications. The test results shown in the firm's batch records could not be duplicated by FDA--our chemists found the methodology simply could not work. We found that the analytical work he did and the test results he provided were fraudulent.

The purveyor of this fraud is now serving time in jail. More importantly, as a result of FDA's review, the safety of our Desert Storm troops was not endangered by distribution of an unreliable product on which they would have been relying on for protection against this chemical warfare agent.

Finally, in 1989 FDA reviewed an NDA for dilevodol, a beta blocker, that was marketed in Europe and about to be launched in the United Kingdom. Our review revealed several cases of severe liver injury that led to non-approval. Subsequently, the sponsor's review of marketing experience in Portugal and Japan also revealed several instances of fatal liver injury, and the drug was withdrawn worldwide.

Finally, we also have to determine that the company can make the drug the same every time, so that batch after batch of the drug has the same therapeutic profile. Through good manufacturing practice inspections we compare what the company puts in its chemistry and manufacturing controls section of its application with what it is actually prepared to do at the manufacturing plant.

FDA has been engaged in a continuous improvement effort that involves identifying ways to reduce regulatory burden and improve our ability to protect and promote public health and safety. We believe that this criteria should be the test by which any reform proposal is measured.

The question presented by the Committee is whether it is feasible, without lowering our safety and efficacy standards, and without additional resources, to meet the review times set forth in S. 1477. S. 1477 requires that by July 1998 the Agency would be reviewing all drugs within 180 days, and priority drugs within 120 days (Sections 103 and 204). Comparable review times would be established for other products.

We have examined this question very carefully and I do not believe that the Agency could meet the product review times set forth in S. 1477, with existing resources, without compromising existing public health protection. Moreover, I believe that by focusing on further reducing drug review times beyond that agreed to in PDUFA we run the risk of undermining the progress we are making toward shortening the overall time it takes to get drugs to patients.

What does it take to review an application within four to six months? First, it takes an excellent application. With only four to six months there would be little opportunity to obtain clarifications or additional information from the sponsor. Although every application could be reviewed exactly as it is submitted, very few applications are so complete and accurately presented as to be approvable without further discussion with the sponsor. Second, it requires having the necessary review staff, including all the various disciplines, ready to work on the application the day it comes in the door. That means other work needs to be put on hold. Third, it means companies will need to be fully ready to manufacture the drug -- so that FDA can start the pre-approval inspection at the same time we start the substantive review. Fourth, the shortened review times will compromise the effectiveness of advisory committees. Particularly for applications that present complex problems or involve substantial public health issues, these committees rely on the Agency to validate, and analyze and present clinical research findings. The timeframes for review and advisory committee consideration jeopardize the Agency's ability to perform this function for the committees.

Shortening review times to those specified in S. 1477 would adversely effect, in a number of ways, the goal of getting safe and effective drugs to consumers as quickly as possible.

First, reviewers will be unable to spend time with sponsors obtaining clarifications or answers to questions that arise in the course of the review. The only way to get the information will be through additional review cycles. That means it will take longer for drugs to get to market. The alternative, though less likely, outcome would be that reviewers will feel compelled to approve drugs based on less information, with fewer analyses and much greater uncertainty for patients and physicians about how the drug works and how safe it is. And that means we will have lowered our standards.

Second, Agency resources devoted to product review would need to be greatly expanded, and existing expertise duplicated many times over. We would need to have enough reviewers in every scientific discipline so that there would be reviewers with the appropriate expertise ready to begin a review the day an application was filed. This would mean that the Agency would need to severely reduce work other than product approval reviews, work that in many instances contributes significantly to public health.

One of the non-product review areas that would suffer, and where the Agency is making important contributions that should reduce the time it takes to get drugs to market, is in helping companies understand in the clinical design phase what they need to do to establish safety and effectiveness. Right now, an unacceptably high number of NDAs are never approved. This means that companies are investing time and money into drugs that should be abandoned or into drug trials that do not demonstrate safety and efficacy. Through a variety of mechanisms, we are trying to help companies better understand what is required to establish safety and effectiveness. For example, we will meet with companies and review their protocols in depth, not limiting our review to the severe flaws that could stop the trial.

We also help guide entire areas of inquiry when we take the clinical efficacy issues for a disease state to advisory committees to gain a common understanding of what all companies need to do in a given area. Similarly, we are helping all companies with their drug development when we work with Japan and the European Union on the international harmonization efforts, through the International Conference on Harmonization, so that clinical trials will be useful in marketing applications all around the world. These early efforts to address overall drug development times are likely to provide far greater value than an incremental reduction in drug review times.

Under the S. 1477 timeframes, the Agency also would be required to limit its involvement in the production and post-approval areas. Both of these are critically important to companies and patients. Drug production problems result in a number of different types of adverse consequences for patients. For example, one recent class I recall involved an albuterol spray that was contaminated with bacteria. The result was that these bacteria were being sprayed into the lungs of the people using the product. In fiscal year 1995, there were 251 product recalls. We need to be able to inspect, monitor production, and protect the public from poorly made drugs that are dangerous or of limited usefulness.

Right now we learn much about a drug after it is on the market. Clinical trials typically involve only hundreds or a few thousands of patients in carefully controlled research settings. Once on the market, they often are prescribed to hundreds of thousands of people. The first several years a drug is on the market teaches us about events that occur in a very low rate, such as the aplastic anemia associated with felbamate, and therefore do not occur in clinical trials. We also learn about reactions related to ordinary medical use, such as the severe anaphylactic reactions caused by zomax that were related to how patients took the drug under ordinary circumstances. This knowledge enables us to adjust labeling and drug availability depending on what we learn after the drug is widely used in practice.

Shortening the review times also will adversely impact Agency programs that are not related to drugs or other product approval process, such as the safety of the blood supply, food safety and tampering, and mammography quality. Our efforts to protect the public from unsafe imported products -- whether it is botulism- contaminated mushrooms or hepatitis-contaminated human tissue, will have to be curtailed. It also will severely curtail our ability to respond appropriately to emerging public health threats, crises, or even to new areas where a little work would have a large payoff.

A number of provisions in S. 1477, in addition to the proposed review times discussed above, that we are concerned cannot pass that test. Rather than going section by section through the bill, I will briefly discuss the most significant of these provisions.

There are several sections of the bill that would establish new and lower product approval standards. For example, Section 407 would establish a new process for approving new uses of existing drugs that would completely bypass the drug approval process. It would establish a procedure for recognizing new uses based on medical practice. Unlike the current requirement, the bill provides that if an off-label use has existed for five years, is "common" among experienced clinicians and is reasonable based upon experience and other confirmatory evidence, that use could be included in the product's labeling. This provision moves us away from the accepted scientific standard of evidence back toward evidence based solely on ancedotal experience. Medical history is replete with examples of products and procedures that were based on medical ancedote, not evidence, and were thought for years by most clinicians to be effective, but later turned out to be useless and sometimes even dangerous. Indeed, when the FDA worked with the National Academy of Sciences National Research Council to review the effectiveness of drugs first sold in the U.S. before the effectiveness standard was set in 1962, 1,124 of 3,443 drugs on the market, being marketed for various claims, were pulled from the market because they were not effective.

We are not saying that individual clinical judgments about individual patients should not be made. They are necessary and appropriate on a patient-by-patient basis. But to base drug and device labeling on such a "pattern of practice" standard would be offering the public far less protection than it has today. It also could have the unintended consequence of becoming a disincentive for companies to collect the data necessary to demonstrate whether off-label uses are effective.

Similarly, Section 702 would virtually eliminate approval of devices for specific uses. It would for the first time recognize any use "included within a general use for a predicate device" as an approved use for 510(k) devices. If enacted as is, this provision would allow a device originally marketed for one clinical indication to later be marketed for other indications, even high risk ones, with only the submission of an abbreviated application (510(k)) that would not document the product's effectiveness for the new indication. Suppose, for example, that a cardiac catheter were originally approved for mapping the electrical activity of the heart. After it is on the market, it is offered for a new use: to save lives by preventing a fatal disturbance of the heart rhythm. Under the bill, it is unlikely that we would be able to ask for data showing whether the catheter worked to save lives or was just a costly and failed false hope. Even worse, if the catheter were to work some of the time, in some kinds of patients, there would be no assurance of clinical data, independent review, or accurate labeling to help doctors sort out who are those patients where it is most likely to work, or most risky.

Furthermore, Section 703 would require the Agency to accept scientifically sound studies in lieu of well-controlled clinical trials for medical devices. Although the phrase "scientifically sound studies" is not defined, it is assumed that what is intended is something less than well controlled clinical trials. In our view this could turn modern day science on its head by instituting a preference in law for lower quality scientific evidence, such as anecdotal reports and case studies in lieu of controlled trials. In essence, this would reverse the most significant component of the 1962 Act, the requirement that sponsors establish that products work before they can be marketed.

We understand that controlled studies are not the only way to show that a drug or device works and they are certainly not the only way used today. But, there is essentially unanimous agreement in the scientific world that they are stronger evidence than the alternatives in this bill. In every case, the Agency would have to assume the burden of not only specifically asking for good science in the form of well-controlled data, but would have to explain why it was being required in lieu of the lower standard.

We agree that a problem exists with the extent to which drugs and devices are being used for indications that have never been approved. Some of those uses likely are beneficial. We know there have been some that were deadly, even though they were thought to be sound medical practice. The solution to this problem, however, should be one that results in the collection and review of the necessary data to establish efficacy, not one which will undermine the efficacy requirement. We would like to work with the Committee on developing those solutions.

We also are concerned that the bill would eliminate FDA's role in assuring that modifications made to a product do not adversely affect its safety and effectiveness. Under the bill, unless the manufacturer's own data show that safety and effectiveness were to diminish, FDA could not require data on the modified product (Section 702 and 707). Yet we know such modifications can carry initially unrecognized risk. Take the case of the soft tissue fixation device used in orthopedic surgery, the device was on the market to be used to anchor soft tissue during shoulder surgery. The manufacturer wanted to change the materials being used and modify the design. After reviewing the data for the proposed modifications, the Agency asked the manufacturer to perform clinical trials. The study showed that the head of the modified device often broke off after the surgery and lodged in the shoulder joint, causing severe pain and often the need for corrective surgery. Further, the modified device could form the basis for new use claims and, as I described previously, there would be no way to assess the scientific basis for the new claims.

We are equally concerned that the bill would remove even the basic assurance that most new devices will be well made. Under Section 702 a company, even one with known manufacturing problems directly relevant to its new device, would have to be given marketing approval even though the Agency has evidence the firm is unable to produce a quality product.

Another area where the bill would decrease the protection of the FDC Act involves consideration of comparative effectiveness. Although the Agency generally does not base its approval decisions on whether one drug works as well as another already approved therapy, there are circumstances where such considerations are very important. For illnesses with significant public health implications, such as measles or sexually transmitted diseases, it would be unconscionable to allow marketing of drugs which are less effective than existing therapies. For example, for products intended to treat gonorhea, the Agency requires a 95 percent efficacy rate. Similarly, vaccines for measles or other highly contagious diseases must be as effective as possible. The same consideration exists for therapies for the treatment of serious or life-threatening illnesses.

For both devices and drugs, the bill apparently would prohibit the Agency from considering uses for which a product could be marketed, unless those uses are explicitly included as label claims (Section 408). It appears this section would even prohibit the Agency from looking at clinical outcomes resulting from use of a device -- for example, whether patients with artificial hearts did well or died -- unless the outcome is part of an explicit label claim.

Section 408 also might prohibit the Agency from requiring sponsors to include in their labeling information about indications for which the drug should not be used. One of the advantages of clinical trials is that they often provide information about when a drug should not be used, as well as information about when it works. Requiring a sponsor to include such information in the labeling can prevent very serious injury. Similarly, restricting the Agency's ability to use information it obtains from adverse reaction reporting and other types of post-marketing surveillance does not make sense.

Fentanyl is a powerful painkiller that was approved for use through a transdermal patch for pain control in patients, such as those with terminal cancer, who had developed a tolerance to opiods. Physicians and dentists began using the patch for conditions like post operative pain, in persons who were not opiod tolerant. This caused severe respiratory distress in some patients, and resulted in several deaths. Based on this experience, the Agency required the sponsor to make significant labeling changes and to include in its labeling a specific warning about this dangerous, unapproved use. Obviously, the sponsor never intended that its product would be used on patients who could not tolerate such powerful medication. Section 408 could limit the Agency's ability to include this type of important information in product labeling.

There are a number of provisions throughout the bill which would allow companies to market products without FDA approval, if the Agency fails to meet review deadlines. Under Section 404, for example, a company that has obtained a European Union approval could market its product without FDA approval if the Agency fails to meet the review time.

The underlying rationale for such provisions appears to be that they would serve as a mechanism for holding the Agency accountable for its performance. The problem with them, however, is that they allow the concept of accountability to completely override the statute's primary objective that drugs and devices be proven to be safe and effective before they can be marketed. Although we fully agree that the Agency must be held accountable for its performance, this can and must be accomplished without sacrificing existing protection.

The concept of marketing approval by default is not new. Prior to the 1962 drug amendments that required sponsors to demonstrate that their products work, drugs could be marketed if the Agency failed to act within specified time frames. Proponents of the amendment to require an affirmative determination by the Agency of safety and efficacy as a prerequisite for marketing approval recognized the critical importance of the Agency's review, and the need to give the Agency greater flexibility in light of the volume of new drug applications, the increasingly more complex nature of such applications and the availability of expert personnel to review those applications.

These same factors motivated Congress in 1990 to change a similar marketing approval by default provision in the device statute. As a result of those changes, the Agency must make an affirmative finding of substantial equivalence for devices to be marketed under the 510(k) clearance process. This change, like that in 1962 for drugs, enhanced the protection afforded the public.

The reliance on approvals by other countries does little to ameliorate the problem. Assuming that a drug or device legally marketed in the European Union should be marketed here simply because of the passage of time places an extraordinary faith in an untested, unevaluated system still in its infancy. Under these provisions, we are concerned that the only way FDA could prevent a European Union-approved product from being marketed in the U.S. would be for FDA to prove that it is unsafe or ineffective. Essentially, this would take us back to the type of drug regulation that existed in this country prior to 1938, with the commensurate significant loss in consumer protection.

It should be noted that although this provision would tie the FDA's hands regarding drug and device approvals, it would not require the same allegiance to foreign government actions for a decision to withdraw marketing approval or not to approve the product in the first place. Under S. 1477, if the European Union or United Kingdom withdraws a drug from the market, it would not automatically be withdrawn in the U.S. Moreover, this provision could provide foreign owned companies, particularly those that are government subsidized, a dangerous competitive tool in the world market.

The bill's requirement for third party reviews is equally troubling. The third party review sanction set forth in Section 743 raises particular concerns, in addition to those generally applicable to the feasibility of third party review. Once the provision is triggered, it would interrupt consideration in the middle of the overall process for many applications. Companies would be faced with having reviews performed by a third party reviewer who has very little knowledge of the specific development process for the drug and/or of the agreements made during that process. The contracting requirement assumes that well trained staff, free of conflicts of interest yet familiar with the regulatory review process will be readily available to perform this work. We doubt whether that would be, in fact, the case.

The feasibility of third party review raises important questions that should be, and are being, carefully examined. FDA's scientists and experts are charged with exercising independent and unbiased judgement. They comply with stringent financial disclosure and conflict of interest requirements designed to protect the decision-making process against bias. It is not clear whether, and how, this independence can be maintained with private sector review organizations. The Agency has initiated two different pilot projects to assess the feasibility of such a program.

The substitution of judgment also extends to the manufacturing area. When a contractor has given a manufacturer good marks for its production processes, FDA is prohibited from inspecting the plant for two years unless the Agency learns through other means that there is something seriously wrong at the plant.

The bill also undermines consumer protection through other default mechanisms. Now, if FDA suspends or revokes the license of a blood bank because it has created a public health danger, it is shipping HIV-contaminated blood, it cannot resume shipments until it has fixed its manufacturing problems. Under S. 1477, a blood bank that has had its license suspended or revoked can resume shipping blood even before it has fixed its manufacturing problems, if the FDA misses the 30 day reinspection deadline by even one day. (Section 606)

Similarly, the changes the bill proposes for review of indirect food additives could result in unsafe food additives being sold if FDA does not fully review an indirect food additive notification and publish its decision on that food additive in the Federal Register within 90 days. (Section 902) The 90 days is an unrealistically short deadline; it would take many FTEs not provided for in this bill, to lower review times to 90 days. Therefore, FDA either will be forced into premature disapprovals, or it will have to watch as the public is exposed to industrial chemicals which pose a potentially serious risk to the public health.

The provisions for treatment access to investigational products are clearly intended to meet real patient needs. But as drafted they go too far. We, too, want patients who have no good treatment options to have access to the newest therapies, even before they have been fully studied and evaluated. We have made experimental drugs available early-on in the process by our use of treatment INDs, parallel track, single patient protocols, and emergency use INDs. But we do it in a way that still permits the basic research on the drug to be done, so that eventually physicians and patients know whether the promising therapy really works, and how best to use it.

Unfortunately, S. 1477 (Section 202) would permit drug and device companies to side-step completely FDA's approval process and go into the manufacture, promotion, and sales of a product for any serious disease or condition without FDA approval. Under S. 1477's provisions, expanded access protocols could be given for any product that diagnoses, monitors, or treats a serious disease or condition, so long as other therapy is not "comparable or satisfactory."

In addition, S. 1477 would permit the manufacturer to widely promote the availability of the expanded-access protocol. (Section 202) Unlike FDA's current system for cost recovery under a treatment IND, there is no requirement in the bill that adequate enrollment be obtained for clinical trials that are designed to determine the safety and effectiveness of the product, and that the manufacturer pursue marketing approval with due diligence. In short, the patient would have to pay full price for an experimental product, and the company would be under no obligation to ever find out its true value. Coupled with the provisions for cost recovery, promotion of the availability of experimental treatments would create a climate where the unscrupulous could sell untested hope with scant risk of being found out and only weak sanctions if they were. The 1995 Health and Human Services Inspector General's review of commercialization of unapproved medical devices shows this is not just a theoretical risk but a predatory business practice hard to control even with today's stronger law.

We agree that advisory committees are an important part of FDA's review processes. We value the guidance and direction we receive from these outside experts. But S. 1477 would create "scientific review groups" that would be expensive, difficult to handle administratively, and would meet so often that we doubt that respected experts would be willing to serve on them. (Section 106)

Perhaps more importantly, the scope of the scientific review groups set up by S. 1477 is so expansive they would have the ability to second-guess any significant scientific decision made by FDA, to an extent that the scientific review groups would become a shadow FDA. Now, advisory committees usually meet three to four times a year; this bill would require that they meet at a minimum six times a year (Section 106), at an increased cost to the Agency of approximately $6,000,000. The costs in fact would be higher, because advisory committees would have to meet much more often in order to hear appeals on every significant decision made by FDA on whether a clinical trial should start, how a protocol should be designed, or whether an application should be accepted for review by the Agency (Section 107). The bill also places other unreasonable demands on both FDA and the review committee members, in that it would triple the time before which meetings must be announced and agendas set, and permits committee members to be inundated with paper and lobbied by companies and other individuals. In short, scientific review committees would impede drug review, not enhance it.

We also think that there must be appropriate methods for appealing decisions made by first-line reviewers, when a company disagrees with such a decision. Those mechanisms exist, and last June I asked the Center directors to review the existing appeal mechanisms, make improvements where possible, and insure that companies are aware of the availability of such mechanisms. There already have been significant changes in how appeals from clinical holds are handled, and the Centers are working hard to train their staffs so fewer decisions need to be appealed. But taking every disagreement to a scientific panel during the entire drug development phase will inhibit, rather than enhance, communication between industry and FDA, creating an adversarial process in place of a cooperative one, and ultimately increasing overall drug review times.

There are a number of provisions in S. 1477 that would dramatically limit the Agency's ability to manage its resources efficiently. These provisions would adversely affect both the product review process and the other public health activities of the Agency. For example the bill orders the Agency to consider certain products (such as radiopharmaceutical drugs) in particular divisions (Section 402); it forces us to keep biologic product licenses, even when we are willing to eliminate them for some types of biologics (Section 606); conversely, it eliminates establishment licenses, even for products that could be most simply and effectively regulated using ELAs. (Section 606) ELA reviews have found examples of cross-contamination and seriously violative air handling systems. In addition, certain technologies may actually be more flexibly regulated by the use of the ELA, for example, cellular and gene therapies, and xenotransplantation products (tissues and organs transplanted from animals to humans). GMPs alone would not be adequate to assure that proper controls are maintained to prevent the spread of infectious diseases.

It should be beyond dispute today that you cannot legislate good management. We need to have clear performance goals and we need to be held accountable for meeting those goals. But we need the flexibility to change in response to changing conditions, reallocate resources to address the most significant public health problems, to respond to emerging issues. Good management comes first and foremost from good managers. I believe we have such managers, and that they should be allowed to do their jobs.

There also are sections of S. 1477 that express laudable goals, but again are so expensive as to be totally unrealistic in this budgetary climate. Information systems (Section 104), the formal publication and compilation of all policy statements (Section 105(B)), the extensive meetings on clinical trial design, and the additional advisory committee meetings would cost more than FDA could conceivably afford to spend in these areas.

Similarly, the time frames specified for a variety of actions, such as reinspections and issuance of regulations are unrealistically short.

I hope the concerns I am expressing about this bill will not be construed as commitment to the status quo. The Agency looks forward to continuing to work with the Committee and others on new ideas on how we assess new product effectiveness, how we get products labeled to reflect the best data on their use, how we get clinical development, and how we get the Agency's independent review of new products to go faster so scientific advances move to the bedside more quickly. I agree that we need to consider alternative ways to determine whether new uses for existing products are sufficiently scientifically credible to be included in a product's labeling. We also recognize that some claims for diagnostic products or surgical tools are supported by different kinds of data from those we generally expect for other kinds of products. We need to describe clearly when this is the case.

There are provisions of this bill that reflect good ideas. As I stated at the beginning, we believe that there is still a great deal that we can do to improve our ability to get safe and effective products to patients as soon as possible. We have a strong foundation in the Prescription Drug User Fee Program, the efforts that have been made under the Administration's reinventing government initiative, and our successes in expediting development and approval of AIDS drugs, on which to build. The Agency and industry have demonstrated that by working together we can develop reasonable solutions to regulatory problems solutions that serve and promote the public health. We look forward to working with the Committee and the industry on finding even more ways to improve the existing system.

ATTACHMENT 1

Experts: toxicologists, pharmacologists

Bulk drug--usually made outside USA

Experts: Clinical pharmacologists, pharmacologists, biopharmaceutics experts, pharmacokineticists

Experts: Clinical pharmacologists, FDA inspectors, medical subspecialists (infectious disease, cancer treatments, AIDS experts, anesthesiologists, etc.), Biostatisticians, clinical trialists

Experts: Chemists, Manufacturing experts, Microbiologists, FDA inspectors

Experts: Regulatory experts, pharmacists, clinicians, clinical pharmacologists, chemists, biopharmaceutics experts, lawyers.

FDA Home Page

| Search | A-Z Index

| Site Map | Contact FDA

FDA/Website Management Staff

Web page updated by jch 2001-JUL-19.