|

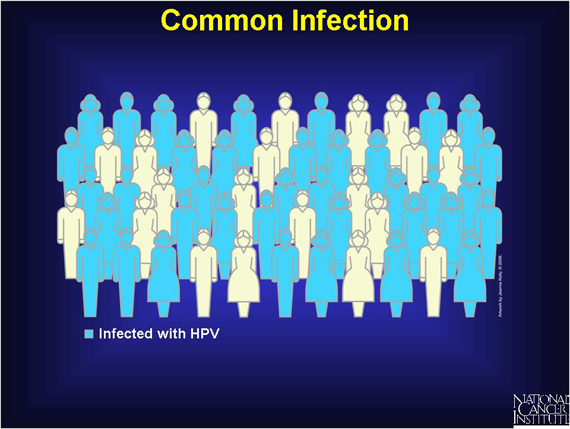

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted virus in the United States. At least 70 percent of sexually active persons will be infected with genital HPV at some time in their lives. HPV infects both men and women.

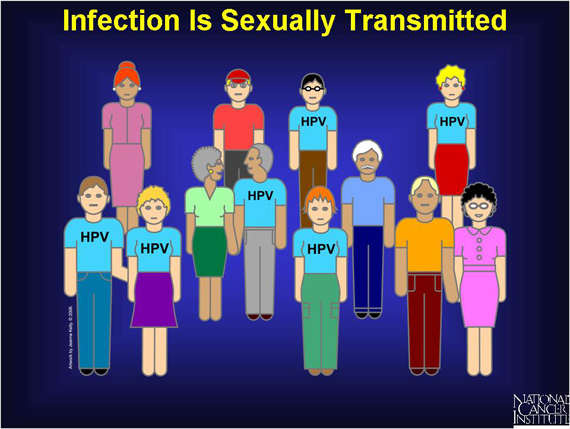

Anyone who has ever had genital contact with another person infected with HPV can get the infection and can pass it to another person. Since the virus can be silent for many years, a person can have genital HPV even if years have passed since he or she had sex.

There are three groups of genital HPV strains: many no-risk types cause neither warts nor cancer; a few types cause genital warts; and 15 or so high-risk types can increase one's risk of cancer.

If left untreated, genital warts do not turn into cancer.

High-risk HPV, on the other hand, may trigger an infection that leads to cervical cancer. The majority of infections with high-risk HPVs clear up on their own. Some infections persist without causing

any additional abnormal cell changes. However, a few infections caused by high-risk HPVs end up triggering cervical cancer over many years.

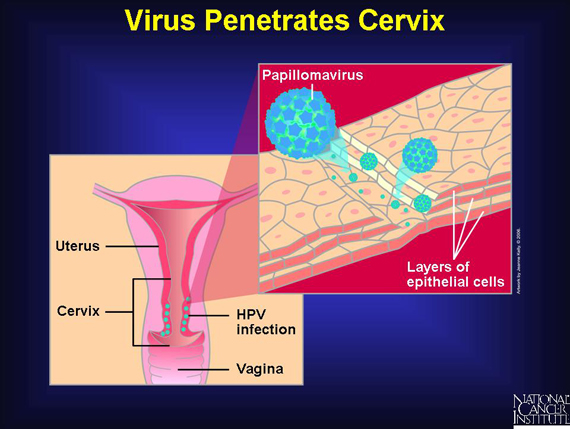

Both harmless and cancer-linked human papillomaviruses pass by skin-to-skin contact. The high-risk types of HPVs need to penetrate deeply into the lining of the cervix to establish a chronic infection. A vaginal sore or sex, which can abrade the lining, may provide a point of entry for the papillomavirus.

Once inside the cervical lining, the virus attaches to epithelial cells. As these cells take in nutrients and other molecules that are normally present in their environment, they also take in the virus. Over 99 percent of cervical cancer cases are linked to long-term infections with high-risk human papillomaviruses.

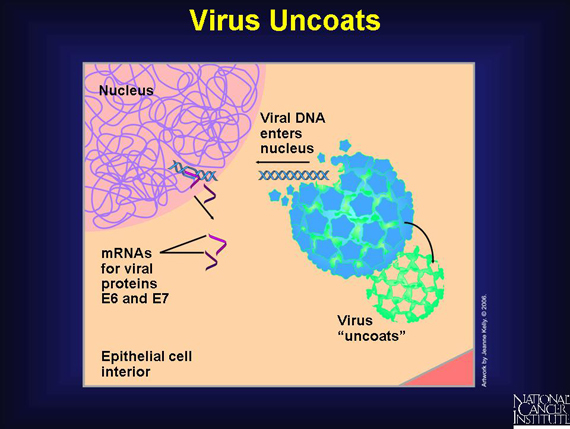

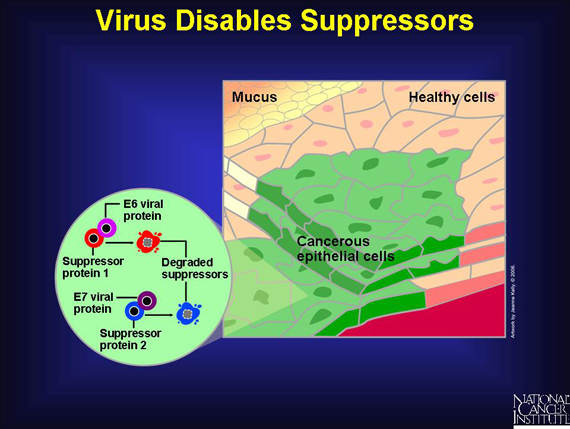

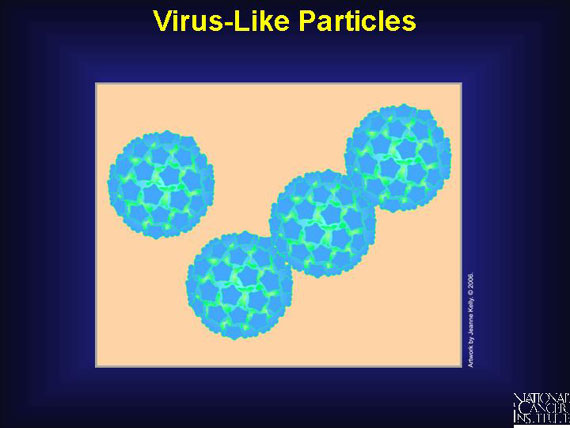

The HPV sits inside the epithelial cells housed in a protective shell made of a viral protein called L1. After the virus enters the cell, the viral coat is degraded, leading to the release of the virus' genetic material into the cell and its nucleus. From the nucleus, the genes of the virus are expressed, including two genes called E6 and E7, which instruct the cell to build viral proteins called E6 and E7.

Viral proteins E6 and E7 then disable the normal activities of the woman's own suppressor genes, which make suppressor proteins that do "damage surveillance" in normal cells. These proteins usually stop cell growth when a serious level of unrepaired genetic damage exists. Even after suppressors are disabled in a woman's cervical cells, it usually takes more than 10 years before the affected tissue becomes cancerous.

The virus-like particles in the HPV vaccine, like the real human papillomavirus, have the same outer L1 protein coat, but they have no genetic material inside. This structure enables the vaccine to induce a strong protective immune response.

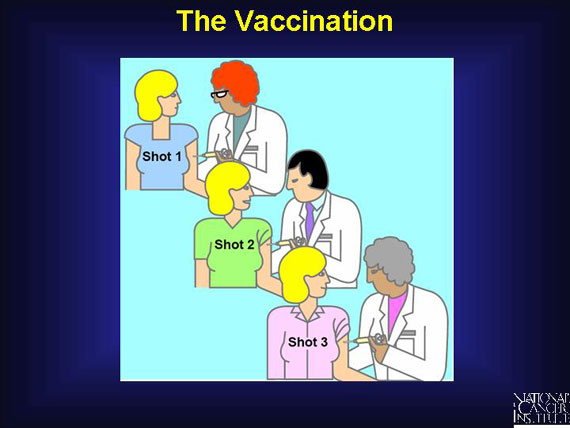

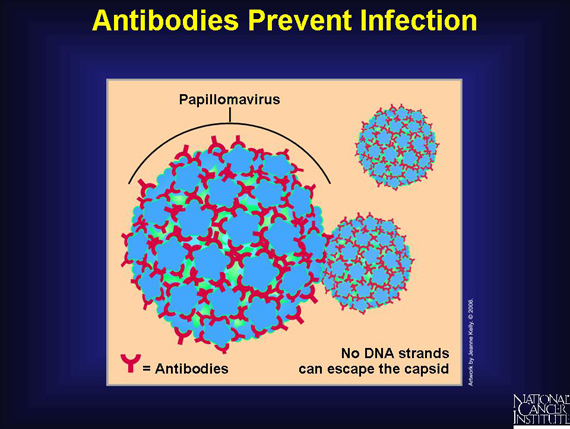

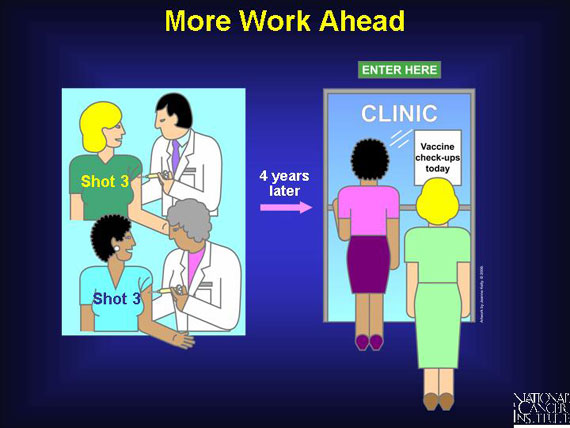

The vaccination protects a person from future infection by the HPV high-risk types that can lead to cancer. It is not a vaccine against cancer itself. A person receives a series of three shots over a 6-month period. Health professionals inject these virus-like particles into muscle tissue. Once inside, these particles trigger a strong immune response, so the vaccinated person's body makes and stockpiles antibodies that can recognize and attack the L1 protein on the surface of HPV viruses.

After the vaccination, the person's immune cells are prepared to fight off future infection by high-risk HPV viruses targeted by the vaccine. If an exposure occurs, the vaccinated person's antibodies against the L1 protein coat the virus and prevent it from releasing its genetic material.

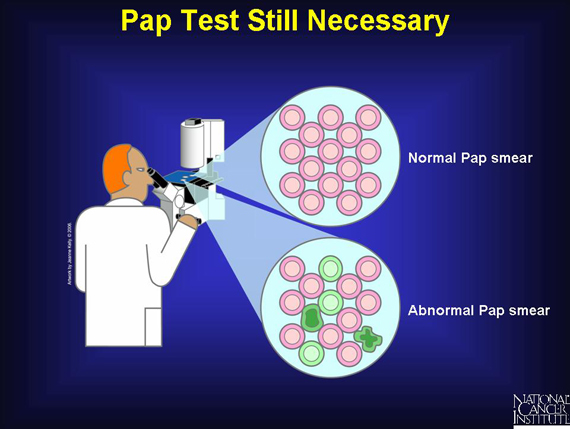

After the vaccination, a woman must still get routine Pap tests or another approved cervical cancer screening test. Although the anti-HPV vaccine prevents infection by the dominant HPV types, which are responsible for 70 percent of the cervical cancer cases, it does not prevent infection by most of the other types that can also cause cervical cancer. A Pap test can detect abnormal cervical growth regardless of what HPV type caused it to develop.

Studies are under way to determine if a booster, in addition to the three initial intramuscular injections, will be necessary for long-term protection. Clinicians know that the new cancer vaccine remains effective for up to at least 4 years, but more research is needed to find out what happens after that time. An NCI study in progress will follow vaccinated women for several more years to obtain information on the vaccine's long-term safety and the extent and duration of its protection.

|