|

|

|

COMPREHENSIVE AND COORDINATED SYSTEMS OF CARE: ELIGIBILITY AND ACCESS BARRIERS

Kenneth Ritchey, M.Ed., M.A.

Director of Ohio Department of Mental Retardation and Developmental Disibilities

Interagency Agreement Between The Ohio Department of Mental Health And The Ohio Department of Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Concerning Ohioans with Mental Illness and Mental Retardation or Developmental Disabilities

I. PURPOSE

WHEREAS, persons with mental retardation or developmental disabilities and co-occurring mental illness are among the most vulnerable of Ohio�s citizens, a cooperative effort among agencies is necessary to assist them to realize their maximum potential and live in the least restrictive setting consistent with their health and safety;

WHEREAS, the Ohio Department of Mental Health (hereinafter, �ODMH�) is the executive agency granted authority pursuant to Chapter 5119 of the Ohio Revised Code to operate, license and/or certify programs for individuals with mental illness, and to provide regulatory oversight of the mental health functions of Alcohol, Drug Addiction, and Mental Health Services Boards and Community Mental Health Boards (hereinafter, �ADAMH/CMH Boards�) which operate pursuant to Chapter 340 of the Ohio Revised Code; and,

WHEREAS, the Ohio Department of Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities (hereinafter, �ODMRDD�) is the executive agency granted authority pursuant to Chapter 5123 and Chapter 5126 of the Ohio Revised Code to operate, license and/or certify programs for individuals with mental retardation and developmental disabilities, and to provide regulatory oversight of County Boards of Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities (hereinafter, �County Boards�) which operate pursuant to Chapter 5126 of the Ohio Revised Code.

Now, therefore, ODMH and ODMRDD hereby subscribe to and support this �Interagency Agreement Concerning Individuals with Co-occurring Mental Illness and Mental Retardation or Developmental Disabilities.�

The specific purposes of this agreement are:

It is the goal of both departments to accomplish these purposes within available resources. It is also a goal of both departments to ensure that the above services are, to the extent possible, based on the needs of each individual.

II. JOINT RESPONSIBILITIES

III. RESPONSIBILITIES OF ODMH

IV.RESPONSIBILTIES OF ODMRDD

V. GENERAL PROVISIONS

VI. Provisions for Compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)

IN WITNESS WHEREOF, the parties� directors have executed this agreement on the dates shown below.

|

|

Date: |

Date: |

Wright State University Project

This project�s goal is to train psychiatric residents to work with individuals with mental retardation and developmental disabilities. Residents are placed in the County Board in order to gain experience with individuals with MR/DD. Outcomes for this project include training Montgomery CB staff in working with this population, teaching psychiatric residents to work with individuals with MR/DD, supervising psychiatric residents who are working with individuals with MR/DD, and providing direct services to individuals served by the Montgomery CB. ODMRDD, ODMH, Montgomery CB of MRDD, and the Montgomery County Board of Mental Health fund this project.

Glenn McCleese will track the stated outcomes.

Coordinating Center of Excellence for Dual Diagnosis

The CCOE will focus on system change. This would be accomplished by the development of local teams to better serve individuals with a dual diagnosis. The CCOE would provide training and consultation to these teams to improve services. In addition, the CCOE would be able to provide assessments of these individuals and conduct research around the types of services necessary to help this population be successful. ODMRDD, ODMH, and DD Council fund this project. The MI/MR Advisory Board would help provide some oversight to the CCOE. Glenn McCleese would track outcomes of the CCOE.

The Wright State project focuses on one aspect of the provision of services to individuals with a dual diagnosis, which is the training of psychiatrist.

The CCOE would focus on creating a local system of care for this population and provide the necessary training to create those systems.

Glenn McCleese will monitor both projects to ensure contract compliance.

INTEGRATING CARE FOR CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL NEEDS IN PUBLICLY FINANCED MANAGED CARE

Sheila A. Pires

Human Service Collaborative

Washington, D.C.

September 2001

This paper was supported by funding from the Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services.

INTRODUCTION

�The world that we have made as a result of the level of thinking we have done thus far creates problems that we cannot solve at the same level at which we created them.� Albert Einstein

Throughout the last decade, there has been an explosion in the use of managed care technologies in the public sector�in State Medicaid programs, in State and local mental health and substance abuse systems, in public child welfare systems and in interagency systems of care operating at local levels.1 At any given time in any given state or locality, there may be multiple managed care initiatives underway that are affecting subpopulations of the same children and families. Particularly for families who must rely on multiple public systems for services and supports, i.e. families of children with special needs, the cacophony of managed care reforms in states threatens to aggravate the fragmentation and confusion that, historically, have plagued children�s services.

This paper defines children2 with special needs to include: children with emotional and behavioral (mental health and/or substance abuse) disorders; children with special physical health care needs; children with developmental disabilities; and children involved in child welfare and juvenile justice systems and their families�recognizing that there may be crossover among all of these populations. From a managed care design and purchasing standpoint, these populations of children and their families have service and/or system involvement that require degrees of customization over and above what is required by the larger population of children involved in public sector managed care. In most cases, managed care represents only one contractual slice of the health and behavioral health delivery system for children with special needs, and the more complex their needs, the more limited, historically, is the managed care slice.

In an effort to access health and behavioral health care, families of children with special needs often become involved, or are at risk for involvement, with multiple systems, including: Medicaid (and the State Children�s Health Insurance Program, if organized separately from Medicaid), mental health, substance abuse, health, maternal and child health (i.e. Title V), early intervention (i.e. Part C), mental retardation/developmental disabilities, child welfare, education and juvenile justice systems. Some children with special needs�but, by no means, all�also are eligible for Medicare and the Supplemental Security Income Program (SSI). For families who have a child with a serious or complex disorder, it is not any one agency but these multiple systems that make up the total health and behavioral health delivery system. Integration of care across these multiple systems, each supported by categorical funding streams, statutes and regulations, poses formidable technical and political challenges for state and local purchasers. This, historically, has been true in fee-for-service systems and continues to be the reality in a managed care environment.

In response to the fragmented nature of the total health and behavioral health delivery system, there has been a movement in the public sector over the past 15-20 years to develop �systems of care� for children with special needs and their families. A system of care is defined here as a broad array of services and supports that is organized into a coordinated network, that integrates care planning and management across multiple systems and that builds meaningful partnerships with families at service and policy levels. While systems of care may be developed on a statewide basis, they are intended to operate locally.

The system of care movement fundamentally is concerned with improving service integration, coordination of care and cost and quality outcomes. These goals are similar to those that many State Medicaid managed care reforms have for a larger population of children and families (within which are included subpopulations of children with special needs and their families). In recent years, systems of care serving children with special needs have adopted managed care technologies, such as case rate financing, organized provider networks, care authorization and care management, and utilization and outcomes management, recognizing the potential of these technologies to lead to better integrated care. In many states, however, local systems of care (whether using managed care technologies or not) are not connected to larger State managed care initiatives, such as those occurring in Medicaid, mental health or child welfare systems, even when those reforms share certain goals with systems of care and are serving many of the same children.

There is an irony to the disconnect that occurs in States between large-scale managed care reforms and local system of care initiatives. Managed care is a technology with considerable potential to improve service integration, care coordination and cost and quality outcomes, particularly for �high utilizers� of services, such as children with special needs. While publicly financed managed care may be approaching this potential, particularly for non high using populations, within any given public system�for example, within State Medicaid programs or within State mental health or child welfare systems�it is in danger of aggravating attainment of these goals across the total delivery system on which children with special needs rely. In addition, systems of care, which focus on improving outcomes for high utilizing populations within the context of the total delivery system, and which, increasingly, make use of managed care tools, are in danger of being marginalized by larger State managed care initiatives.

Increasingly, state and local officials, managed care organizations, families, providers and advocates are becoming aware of these issues. In a number of states and locales, these stakeholders are struggling in a deliberate fashion with how to achieve better service integration and outcomes for children with special needs and their families within the total delivery system in a managed care environment, and some are implementing promising approaches.

A fundamental question facing state purchasers is the degree to which the customization required by children with special needs should and can occur within the managed care system or should remain outside the system, with clearly defined pathways between what is built in or kept out. Systems of care are, by definition, customized approaches to integrating care for children with special needs and their families. Where they exist or can be developed, they offer an approach, through inclusion in or formal linkage with large-scale managed care, to improve service integration for children with special needs.

The purpose of this paper is to explore some of the issues and challenges facing states in this area and raise the potential for fit between large-scale public sector managed care initiatives and systems of care focusing on subpopulations of children with special needs. The paper hopes to stimulate new ways of thinking about both managed care and systems of care so that the potential of both may be realized. From a family�s standpoint, the total delivery system should look more seamless, rather than more fragmented, as a result.

TODAY�S UNIVERSE OF PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGED CARE AND SYSTEMS OF CARE

What Exists Today?

While there are variations on the following�and categorizations of public sector managed care tend to be problematic as a result�currently, there are essentially the following types of managed care initiatives, as well as systems of care, underway in the public sector that affect children with special needs:

Systems of care may or may not be using managed care approaches, but like the managed care initiatives for �high utilizing� populations described above, they tend to focus on children who are involved, or are at risk for involvement, in deep end services. Similarly, they tend to blend or access funds from across children�s systems to support a broad, flexible array of services and supports, and are focusing on a relatively small target population in a given locale. Like their counterpart above, they also tend to have interagency policy bodies with family involvement.

Any given state, at any given time, may have all four types of public sector managed care underway as described above, as well as systems of care. Although there is cross over among the populations each serves, each may be planned and operated on separate tracks.

Disconnect Between Managed Care and Systems of Care

There are structural, philosophical and political reasons underlying the disconnect that may exist in states between large-scale managed care initiatives, such as Medicaid managed care, and system of care initiatives. For example, in some states, large-scale managed care initiatives may be designed structurally as acute care reforms, providing brief, short term treatment for a total eligible population of children (for example, all Medicaid eligible children). Systems of care are usually designed to provide extended care to a smaller subset of a total eligible population (for example, children who have serious disorders). Managed care initiatives in these instances may be using �acute care� dollars, while systems of care are using extended care dollars.

Philosophically, large-scale managed care initiatives may employ more of a medical model approach, applying more narrow medical necessity criteria than would be used in systems of care that are using more of a psycho social necessity approach. Large-scale managed care networks may include primarily traditional clinical services, while systems of care are utilizing a broad array of both traditional clinical services, home and community-based services and natural supports. Additionally, managed care may have less of a focus on family involvement at both service and systems levels than systems of care, and less of a focus on cultural competence at all levels of the system. For example, research has found that family involvement in Medicaid managed care reforms, particularly in integrated physical/behavioral health designs, primarily is concerned with involving families in treatment planning for their own children, while systems of care seek to involve families at all levels as partners in system and services implementation. Similarly, cultural competence in managed care concerns itself primarily with such matters as having bilingual providers and materials translated, while systems of care seek to infuse cultural competence into all levels of systems and services operations.4

Politically, managed care tends to be driven and governed by state Medicaid agency concerns and policies, which, at this stage at least, tend to focus more on access and cost outcomes than do systems of care, which are more concerned with improving services integration and child/family functional outcomes. While they may involve state Medicaid agencies, systems of care tend to be driven and governed by children�s agencies. While there remains a disconnect between systems of care and large-scale managed care reforms in many states, they are not, inherently, opposing forces, and, developmentally, both may have reached a stage where they can inform each other. As noted, systems of care are gaining familiarity with managed care technologies, and large-scale managed care initiatives, as they increasingly enroll populations of children with special needs, can learn from the experience of systems of care, which are tackling some of the issues and challenges involved in integrating care for children with special needs and their families. As discussed in Sara Rosenbaum�s accompanying analysis, through their purchasing specifications, states are experimenting with a variety of ways to customize care that include aspects of systems of care.

EXPLORING ISSUES AND CHALLENGES

Population Issues

Who Depends on Public Systems?

One of the first challenges to designing a more integrated delivery system for children with special needs within managed care is defining the population. To reach a definition of children with special needs, one must begin with a picture of who the total population is that depends on public systems for services and supports, within which are subpopulations of children with special needs. The total population includes:

Because private insurance rarely covers more than brief, short term health and behavioral health care, families who have a child with a serious or complex disorder, regardless of income, typically end up having to turn to the public sector, along with families who are poor or uninsured and for whom the public system is the only option.*

Disaggregating the Population

In thinking about how to design a delivery system for the total population of children that depends on public systems, within which there are subpopulations of children with special needs, it is critical to disaggregate both the total population and the subpopulations by certain characteristics� i.e. by population, service and system involvement characteristics. In so doing, managed care designers and purchasers can begin to define subpopulations of children who require customization and the degree of customization entailed. Closer analysis of population characteristics can support more informed cost and quality benefit analyses regarding what to customize within managed care and what to leave outside of managed care with clearly defined pathways between the two. For example, within the total eligible population is a subpopulation of children who have behavioral health problems. This subpopulation can be further disaggregated to include children who have need for only brief, short-term treatment, those with intermediate care needs and those requiring extended services and supports. Creating a traditional benefit package of limited outpatient and hospital care may suffice for the subpopulation needing only short-term treatment, but will not be adequate for the rest.

Similarly, within the total eligible population are families who are involved with the child welfare system. These include families who have come to the attention of child protective services, those who are foster parents, adoptive parents of special needs children and those who have become involved in the system to access a particular type of service, such as therapeutic foster care. Within the subpopulation of children and families involved in the child welfare system, there tends to be an over- representation (in comparison to the total population dependent on public systems) of certain children and adolescents and of particular service needs. For example, child welfare systems today are serving a disproportionate number of infants and preschoolers at risk for emotional and developmental delays; there are disproportionate numbers of older adolescents who are transitioning out of foster care; there are a disproportionate number of families in which substance abuse is an issue; and there are disproportionate numbers of children with dual diagnoses of emotional and developmental disorders, with conduct disorders, with sexual impulse control issues and with sexual abuse treatment needs. In addition, children in the child welfare system require customized responses because of the nature of the system in which they are involved. For example, due to multiple placements, they are far more mobile than the total population that depends on public services, safety and permanence are critical issues, and the courts play a role in the lives of many of these children and families.**

The total eligible population includes other sub-populations of children who bring unique characteristics. For example, there are significant percentages of children and adolescents who are involved in the juvenile justice and special education systems, for whom there also are unique population, service and system characteristics. There are children with special physical health care needs and with developmental disabilities, and there is tremendous variation in service use and cost depending on type of disability or disorder. For example, recent studies indicate that inpatient costs represent about 83% of total costs for children with chronic respiratory disease, but only 28% of the total cost of care for children with cerebral palsy.5 There are also, of course, significant percentages of children with dual or multiple disorders, for example, children with behavioral health and developmental disorders.

The unique characteristics of the various subpopulations of children within the total eligible population carry implications for a host of system design and purchasing variables�e.g. for the types of stakeholders that need to be at the system design table; for the types of services and supports that are included in managed care arrangements; for the types of providers that are involved in networks; for the relationships that have to be in place with juvenile court judges, with child protective services workers, with probation officers, with special education placement processes; and for governance and liability arrangements. Population characteristics also need to inform determination of capitation and/or case rates and risk structuring, including the need for particular types of risk adjustment mechanisms. The greater State purchasers� understanding of the unique characteristics of children with special needs, the more informed decisions they can make about whether and what to customize within managed care and what to leave outside of managed care that will require defined coordination pathways.

How Children Use Services

In addition to understanding who uses public systems, it also is helpful to examine how children with special needs tend to use services. Typically, within the total population of children who depend on public systems, while there may be regional variation, most children�60-70%�will require no more than brief, short term care. For most of these children, managed care arrangements in Medicaid and in mental health seem to be improving access to services. For the remaining 30-40% of children, however, those who require intermediate to extended health and behavioral health care, (which includes children with special needs), managed care in these systems, for the most part, has done little to clarify, and, in some cases, has aggravated, accountability for service provision across children�s systems (although managed care is focusing greater attention on the fragmentation problem).6 This is particularly the case for the 7-10% of families who have a child with a serious health or behavioral health disorder, who require an array of services and supports, at varying times and in varying intensity, over an extended period of time and who, typically, utilize about 70% of the resources in state systems. Managed care reforms in Medicaid and in mental health agencies are not managing total health and behavioral health care for these highest utilizers of services. Systems of care, where they exist, may be managing total care for these families and children, but are more likely to be sharing service responsibility with State Medicaid or mental health managed care systems that retain acute care responsibility. Typically, the pathways between the acute care systems and extended systems of care have not been clarified, leading to the potential for (and accusations of) cost shifting, as well as confusion for children and families.

The fragmentation in service delivery for children with special needs within managed care systems must be put into the historical context of the fragmentation within fee-for-service systems. Managed care, unlike fee-forservice systems, at least carries the potential, and, in some cases, the reality of more integrated care. For example, managed care systems can create medical homes or lead agencies to coordinate care, and waivers that enroll children with special health care needs in managed care are required to incorporate care coordination and coordination with health services outside the boundaries of managed care that receive federal funding.

Looking at how children in the total population use services carries implications for system design. Specialized features, beyond what is designed for the majority of families with brief, short-term needs, have to be incorporated into the system for families who have children with intermediate to extended care needs. These features might include, for example, wholesale inclusion or development of systems of care within the total system, or if not inclusion, creation of clearly defined pathways to extended care from acute care systems.

Financing Issues

What is Being Depended Upon?

The fundamental challenge to creating an integrated, managed delivery system for children with special needs and their families is the multiple, categorical nature of children�s financing streams and delivery systems in the public sector. The following table presents a picture of various financing streams that support health and behavioral health services in the public sector. It may not be a complete picture in some states and it may overstate the number of funding streams in others, but on balance, it is a representative depiction.

Examples of Health and Behavioral Funding Streams |

||

|

Medicaid |

Mental Health |

Child Welfare |

|

Juvenile Justice |

Education |

Health |

|

State Children�s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) Other *Medicaid match dollars are general revenue dollars allocated as Medicaid match. |

||

Delivery Systems Supported by Different Financing Streams

Typically, each of these funding streams supports a distinct service delivery system, although, from a family�s standpoint, the systems appear to overlap, and there often is confusion as to which delivery system should be accessed at what stage. Some of these funding streams support acute care systems only (i.e. brief, short-term treatment); others support more extended care systems. Typically, the pathways between the acute care systems and extended care are unclear, and, typically, the extended care systems form, in toto, their own irrational �system�. For example, a family with private coverage, who is not involved with the child welfare or juvenile justice systems but who has a child with a serious behavioral health disorder, may turn to the mental health system or special education system for services if their private coverage is exhausted or if it will not cover a particular type of service. If services are not available through those systems, families might then have to turn to the child welfare system, sometimes being required to relinquish custody of their child to obtain services from that system. The youngster in that family might also end up in the juvenile justice system, particularly if services cannot be obtained and behavioral problems escalate. For children with special needs, this is not an uncommon scenario but certainly an irrational one.

Each of these funding streams also tends to support distinct contracting arrangements, although there may be overlap among the contracted services each funding stream is supporting. Providers often have separate contracts with several of these systems, each with different contractual requirements, even though, sometimes, the same services are being purchased and the same children are being served.

Each of these funding streams is handled differently in each state, depending upon state structure and policy. Some states, for example, decentralize some of these funds to counties; others centralize administration of funds. If decentralized, funds may be administered differently in each county.

It is impossible to understate the politics that surround categorical funding streams and delivery systems at state and local levels. The public agencies that control these funds and the providers and consumers who depend upon them often guard their distribution, or re-distribution, closely, even when there is political rhetoric for more integrated service delivery. The fears of agencies, providers and consumers of letting go of these monies are not necessarily unfounded. The history of block granting formerly categorical monies, for example, too often has been associated with fund erosion. On the other hand, the newer generation of �blended or braided funding�, found predominantly in systems of care, demonstrates the possibility of achieving more rational, integrated (whether �virtually� or actually integrated) financing arrangements for children with special needs and their families. Perpetuation of categorical financing, however well intended, also perpetuates the fragmentation in children�s services.

In addition to the politics surrounding categorical funding streams, the distinct legal and administrative requirements attached to each pose technical barriers to integration. However, the potential also exists at federal, state and local levels to waive many of these requirements, and the fact that some jurisdictions have done so, albeit on a small scale, holds promise for more widespread systemic flexibility.

Which Types of Dollars Are Used in Managed Care?

Theoretically, managed care could be a powerful tool for de-categorizing dollars. Capitation and case rate financing allow for flexibility in dollar allocation in exchange for meeting specified outcomes. In reality, however, most public sector managed care initiatives to date utilize only a handful of categorical funding streams; they may introduce flexibility into the disbursement of one or two streams but do very little to create flexibility across the multiple funding streams for children. In fact, because any given managed care initiative tends to harden the boundaries around the particular dollars it uses, managed care, ironically, may aggravate the categorical nature of children�s spending.

A study focusing on behavioral health managed care in the public sector, principally Medicaid managed care, found that, of ten states studied in 1997, all ten left outside their Medicaid managed care systems various behavioral health financing streams for children. Six of the ten states designed their initiatives to provide only acute care, using only Medicaid outpatient and inpatient dollars. Four of the ten (all behavioral health carve outs) incorporated both acute and extended care into their Medicaid reforms, using, typically, Medicaid outpatient, inpatient, rehabilitative services and, in some cases, behavioral health general revenue and block grant monies. Even these four, however, left behavioral health treatment dollars in other child-serving systems, typically in child welfare, juvenile justice and/or special education, even though children involved in those systems were enrolled in managed care. More recently, the study found that of 35 Medicaid managed care reforms in 34 states, 32 (91%) left Medicaid fee-for-service dollars outside of the managed care system in other children�s systems (i.e. in education, child welfare, juvenile justice, children�s mental health and mental retardation/developmental disabilities).7,8

As noted, there are a host of political, policy and operational reasons as to why categorical financing streams are left outside managed care initiatives, including the legitimate desire to leave a �safety net� in place for children with serious disorders. However, this desire says more about the historical difficulty managed care has had in effectively serving children with serious disorders than it does about its potential to lead to better care. Stakeholders in all ten states noted above reported that the managed care design�s failure to integrate acute and extended care financing streams was aggravating fragmentation, duplication and confusion in children�s services. At the same time, stakeholders expressed serious reservations about whether managed care could or would be designed and implemented in ways that protected the most vulnerable children and families. This ambivalence has led to a kind of stasis in some states in which managed care continues to be designed and implemented in fairly traditional fashion patterned after the commercial sector, in response to which categorical systems become ever more turf protective. In some states and counties, however, stakeholders across systems have entered into partnerships with plans, providers and families to try to activate the potential of managed care to improve service integration by drawing on multiple funding streams through blended or coordinated funding approaches.

Data Issues

Another major challenge to integrating care for children with special needs in managed care is the relative unavailability of data that provide a true picture across the total delivery system of how many children (and which children) with special needs use services, which services they use, how much they use and how much service costs. Like the dollars, data tend to be spread across multiple systems, may be of poor quality or simply are not captured in a way that is useful for managed care design and purchasing purposes. Child welfare and juvenile justice systems, for example, often do not disaggregate health and behavioral health expenditures from larger service contracts. Medicaid agencies typically do not capture general revenue and other expenditures for health and behavioral health spent by other systems that are not Medicaid match dollars. Medicaid service utilization data for the SSI population, for example, picks up only a fraction of service use by children with special needs because many children with special needs cannot qualify for SSI, in spite of serious disorders and heavy service use. A recent analysis of Medicaid expenditures conducted by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, for example, found that among children and adolescent �high cost� users of mental health and substance abuse services paid for by Medicaid, only one third were SSI recipients.9 The rest fell into other Medicaid eligibility categories and would have been missed by an SSI carve out seeking to manage care for high utilizing Medicaid populations.

Rate and Risk Structuring Challenges

Not surprisingly, given the lack of data providing a reliable picture of service utilization and cost by children with special needs and the multiplicity of agencies and funding streams involved in their care, rate and risk structuring is another challenge. There are a few models for rate and risk structuring for discrete subpopulations of children, for example, for the child welfare population, for children with serious emotional disorders and for certain populations of children with special physical health care needs. However, there are not reliable, tested models for rate and risk structuring across a total eligible population that includes the subpopulations of children with special needs defined in this paper. The variability within the subpopulations of children with special needs makes rate and risk structuring difficult, as does the so-called �woodwork effect� (that is, accounting in rate and risk structuring for a surge in demand in response to the availability of a more integrated system of care).

The traditional rate structuring approaches that are based on age, gender and demographics are not sufficient for children with special needs populations. Reliable rate structuring for these populations is more likely to be based on clinical or functional status and/or diagnostic criteria. It may be possible to utilize the experience of states that have developed risk adjusted rates and risk sharing arrangements for discrete subpopulations of children (e.g. children involved in child welfare) to begin to develop total population rate and risk structuring approaches. This experience includes both systems of care and managed care initiatives that are using case rates, rather than capitation, for subpopulations of children with special needs, and a variety of risk sharing arrangements, including risk pools, reinsurance, risk corridors and the like. It has been argued that, for children with special needs, case rates inherently make more sense than capitation rates since these are children who will use services.10,11 Risk-based financing will not have much impact on whether these children use services but can affect the types and amount of services that they use. For example, early intervention and crisis planning might prevent use of emergency rooms and hospital beds; home and community based alternatives might prevent more costly use of inpatient and residential care.

In addition to rate and risk structuring at the MCO level, customization also is necessary with respect to compensation arrangements at the provider level. For example, compensation needs to factor in the costs associated with the time providers spend having to coordinate care across multiple providers and systems and working with families to increase their knowledge and capacity to care for their children.

Benefit Design Issues

Children with special needs also require customization of the benefit package. The more traditional the benefit design (i.e. the more it resembles a commercial managed care package), the more customization will be required. The system of care movement suggests that children with special needs require access to a broad benefit design, one that covers a broad array of services and supports (including informal and natural supports). Systems of care also suggest that the benefit needs to be flexible, i.e. not constrained by artificial day or visit limits, to support an individualized, �wraparound� approach to service delivery, which is needed by children who have multiple and complex issues and whose needs change frequently as children develop over time. Additionally, the manner and setting for service delivery must go beyond the medical model approach of physician office, outpatient clinic and hospital based care to encompass non traditional and natural settings, including home and school.

Precisely because it incorporates management mechanisms, such as utilization management, managed care offers the potential for states to cover a broad, flexible array of services and supports while controlling cost, and some states, particularly carve outs, are doing so. In some cases, the degree of customization may be greater than some state purchasers are willing or able to undertake. In that event, clearly defined pathways are needed between the services and supports covered under managed care and those available through other child-serving systems. If state designers take a population focus and consider the total delivery system as defined here, they can make more informed decisions about what to purchase within managed care and what to leave outside with coordination pathways in place.

Another challenge is to allow �room� within the benefit design for incorporation of efficacy-based treatment approaches. New data are continually emerging regarding treatment approaches that show promise for different subpopulations of children with special needs. These treatment approaches may look very different from what managed care typically has covered. For example, recent studies pertaining to children�s behavioral health treatment indicate that there is the least amount of efficacy data for those services on which there has been, historically, the most reliance for children with serious disorders, namely, inpatient hospitalization and residential treatment. Conversely, there is increasing evidence of treatment efficacy for some newer approaches, such as Multi-Systemic Therapy, an in-home service approach, and intensive case management approaches.12

Enrollment and Disenrollment Issues

Children with special needs encounter unique enrollment and disenrollment issues over and above those faced by the general population enrolled in managed care. Identification and enrollment of children with special needs may call for customized approaches beyond what is put in place for the larger population. For example, there are existing, federally mandated structures in place in states to find, screen and assess children with special needs, including EPSDT, Part C (early intervention) programs, Title V and other �child find� efforts. There are no doubt differences among the screening and assessment instruments being used within the managed care system and these other programs, which pose integration challenges. If not incorporating these efforts, managed care systems need to develop coordinated linkages with them.

Because of federal regulations governing Medicaid or state design parameters, certain subpopulations of children with special needs will become disenrolled from managed care as they move from one placement to another. For example, youth involved in the juvenile justice system can be enrolled in managed care if they are in a community setting but must be disenrolled if they enter a state detention facility. Many state plans cover children involved in the child welfare system but may disenroll them if they are in state custody or enter certain treatment facilities, such as residential treatment. Continuity of care may be threatened by these unique disenrollment issues. State purchasers need to consider the impact of disenrollment parameters on children with special needs through a somewhat different lens than for the larger population.

Clinical Decision Making Protocol Issues

Another issue facing purchasers of managed care for children with special needs is the need for, and general lack of, customized clinical decision making tools, including screening and assessment instruments, level of care protocols, parameters around utilization, and the like. There are a variety of reasons for this. In some arenas, for example, children�s mental health, efficacy-based treatment protocols are poorly developed in the field in general so it is not surprising to find a scarcity of relevant clinical decision making tools within publicly financed managed care. Clinical protocols historically used in commercial managed care tend to have little relevance for children with serious and complex disorders who are involved with multiple public systems. The conclusive treatment guidelines found in the industry are not readily applicable to children with special needs who fall outside of �usual and customary standards of care�. The public sector has begun relatively recently to enroll children involved in child welfare and juvenile justice systems in managed care arrangements so protocols relevant to these populations within managed care also are in early developmental stages.

On the other hand, state designers and purchasers of managed care are beginning to take steps to develop clinical decision making protocols with greater relevance for �high utilizing populations� in managed care, including children with special needs. Most states, for example, have broadened medical necessity criteria to allow for consideration of psychosocial and environmental considerations, in addition to purely �medical� criteria. States, particularly those with carve outs, are developing level of care criteria specific to various populations of children with special needs. Also, there is a growing body of knowledge developing in the system of care movement with respect to clinical decision making criteria and protocols for children with special needs that can help to inform state purchasers of managed care.

Care Coordination Issues

Children with special needs require a level of care coordination that, historically, has eluded fee-for-service systems and which, not surprisingly, poses major challenges within managed care arrangements as well. As noted earlier, children with special needs tend to be involved with multiple providers and systems, and those involvements change, sometimes frequently, over time. The process of coordinating care takes time and, historically, has not been reimbursed, certainly not by commercial managed care. Yet, managed care in the public sector has far greater potential than fee-for-service arrangements to lodge accountability for care coordination� within medical homes, lead provider agencies, care management entities and the like. It is a characteristic of systems of care to create this type of accountable entity.

If one is taking a population focus and thus considering the total delivery system, care coordination has to be approached as both an �intra� and �inter� issue in managed care�that is, state purchasers need to be concerned about both the coordination of care provided within the managed care system and coordination between the managed care system and other child-serving systems. Systems of care tend to utilize �child and family care planning teams� to hold multiple providers and systems accountable, as well as a designated care manager to ensure that families can utilize services and supports effectively and efficiently across providers and systems. These are strategies that can be incorporated into larger managed care initiatives as well, or, alternatively, organized pathways developed between the managed care initiative and systems of care that provide customized care coordination.

Cross-System Trouble Shooting Mechanisms

Related to the issue of care coordination at the service delivery level is that of interagency coordination at the larger systems level, that is, at the state (and county) policy and administrative levels. When children with special needs are enrolled in Medicaid managed care, the other systems that share responsibility for their care�e.g. child welfare, education, juvenile justice, mental retardation/developmental disabilities, maternal and child health programs, etc.�become, in effect, �consumers� of managed care, that is, they are using the managed care system to provide for some (or all) of the treatment needs of the children they also serve. In addition, by enrolling children with special needs, the larger managed care system assumes shared liability for these children. Numerous policy and operational issues need to be negotiated among these multiple systems, and re-negotiated over time as implementation issues arise. Increasingly, states are creating cross-system policy making and trouble shooting mechanisms to support coordinated pathways to care at the service level and resolve issues such as liability at the policy level.

Network Adequacy Issues

The network that is developed for the larger population is unlikely to meet the diverse requirements of children with special needs and so, once again, customization is needed. For example, children involved in child welfare need access to specialty providers in sexual abuse treatment, among others; children with special physical health care needs require access to a range of pediatric specialists, and they, as well as children with serious behavioral health disorders, need access to a range of home and community based service providers.

Recognizing the need for customization is one thing; knowing how to customize is quite another. There are few algorithms that clarify �how much of what is needed�, that is, that define adequacy within a network serving children with special needs (and, of course, the more subpopulations of children with special needs that are encompassed, the more complicated the challenge). On the other hand, there are systems of care serving various subpopulations of children with special needs that are amassing operational experience with network development that may offer parameters for network adequacy.

Even with a better sense of network parameters, state and county purchasers of managed care for children with special needs must still contend with the historic challenge of insufficient service capacity. There simply is not adequate service capacity available to the public sector among certain specialties, for example, child psychiatrists in many parts of the country, or among certain treatment modalities, particularly home and community-based alternatives to institutional care, or among racial, ethnic and linguistically diverse providers. This is particularly, though not solely, an issue in rural and inner city communities. Re-direction of dollars from inpatient, institutional and residential settings to home and community-based alternatives is a key strategy for augmenting needed service capacity within existing fiscal constraints, and it is a strategy that can be enhanced by managed care through its capacity to incentivize network parameters.

The issue of insufficient service capacity is one that may be aggravated or alleviated by managed care. Inadequate rates paid by Medicaid, increased administrative burdens imposed on providers by managed care, and onerous utilization management procedures all can aggravate the supply problem. On the other hand, some state purchasers have used managed care as an opportunity to broaden Medicaid provider panels and to increase rates through risk-based contracting arrangements, including case rates and performance incentives. In addition, some managed care systems create a favorable trade-off for providers between enhanced flexibility and greater accountability that encourages them to join networks.

Network adequacy in managed care for children with special needs also must concern itself with the availability of informal and natural supports for families and the interface between these and more formal, clinical services. Again, this requires a degree of customization over and above what may be required for the general population. Systems of care are developing experience with linking treatment services and informal supports in a coordinated, holistic services approach that is instructive for large-scale public sector managed care initiatives focusing on a total population of children, including those with special needs.

Accountability System Challenges

The products available through the commercial managed care industry that pertain to accountability systems, such as quality and outcome measurement and even utilization management, are not particularly relevant to children with special needs, though adaptation is possible. Industry accountability products have developed from experience serving, primarily, commercially insured, acute care populations. Quality, cost and outcome measures, and utilization parameters pertaining to care for children with special needs may look very different from those developed for a commercially insured, acute care population. For example, safety (child safety and community safety) is an important measure to track for the child welfare and juvenile justice populations, and one that is not likely to be incorporated into industry standards. The managed care system may not have lead responsibility for ensuring the safety of these children or of the community, but it can be argued that it shares responsibility with other publicly financed agencies when it enrolls these populations. Thus, �safety� becomes a measure that must be incorporated into accountability systems in managed care initiatives serving children with special needs, and safety as a measure requires customization both beyond what is required by the larger population, as well as in its own right to be responsive to the particular mandates of the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, respectively.

The public child-serving systems that historically have served children with special needs only recently have begun to develop quality and outcome measurement systems; most are in early developmental stages, and most do not have experience with utilization management. Thus, publicly financed managed care faces the challenge of adapting or developing new accountability systems. This is another area where the experience of systems of care may be instructive.

Cost measurement systems also require customization, especially if a state is interested in knowing the total cost of health and behavioral health care for children with special needs. As noted earlier, it is rare for the managed care system to control all of the dollars that support health and behavioral health care delivery for children with special needs. Assuming interest in tracking total cost (and cost shifting), states face the challenge of coordinating cost measurement across systems. Again, some systems of care have begun to develop cost data for certain subpopulations of children with special needs that begin to approximate a total cost of treatment picture.

State purchasers have been especially reliant on commercial managed care companies for utilization management expertise. However, this experience derives primarily from managing commercially insured populations. Customization is needed for managing utilization by children with special needs who are involved with multiple public systems. By definition, these children are �high utilizers�, but within their ranks are also outliers. Because, as has been mentioned, the state of the art and existing data regarding expected levels of utilization are poorly developed, developing utilization parameters is an ongoing challenge. Because they operate across systems, systems of care, where they exist, may have a clearer sense of utilization parameters than any one agency serving children with special needs at the state level.

Monitoring satisfaction with services on the part of families and youth with special needs also requires customization. A number of state purchasers have implemented targeted strategies, such as focus groups or contracts with family organizations, to measure satisfaction.

Issues Related to Partnering with Families and Cultural Competence

Systems of care recognize the critical role played by families as the primary care givers for their children on an ongoing basis and incorporate strategies that respect and build on the capacity of families. This makes sense from both a quality and cost of care standpoint. Development of meaningful partnerships with families at service and systems levels takes time and may require changes in attitudes and skills on the part of both families and providers. The kind of enduring and active partnerships needed with families who have children with special needs entails customized approaches beyond what is needed for the general population of children with brief, acute care needs.

A very basic, critical support for families of children with special needs is access to reliable information. Some states are contracting with family organizations to develop family information centers tied to managed care systems. Another resource for families is access to peer support, that is, support from families who have children with special needs and share similar experiences. Again, a number of states are contracting with family organizations to develop peer support networks accessible through managed care systems. Both systems of care and managed care systems are employing family members as care managers and family advocates. These are just some of the examples of customized approaches state purchasers are taking to partner with families, recognizing, utilizing, and building the capacity of families as primary care givers.

Cultural competence is an issue in public sector managed care in general, but it takes on additional significance with respect to children with special needs. In the first instance, children of racial and ethnic minority status are over represented in the population of children with special needs so that culturally relevant service approaches and outreach are especially important. Racial and ethnic minority children with special needs also tend to be over represented in �deep end�, more restrictive levels of care and under represented in home and community based services. As noted earlier, there is a shortage of racial and ethnic minority providers, particularly within specialty areas. Typical purchasing specifications pertaining to cultural competence requirements for provider networks, for outreach efforts and the like may not be sufficiently customized to encompass children with special needs.

CREATING A FIT BETWEEN SYSTEMS OF CARE AND MANAGED CARE

The question raised by today�s universe of public sector managed care and systems of care initiatives is not whether managed care can be applied to systems of care. That is being done already in system of care demonstrations around the country where managed care technologies, such as case rate financing, organized provider networks, care authorization, utilization management and outcomes monitoring, are being employed. Rather, the question is whether systems of care and large-scale public sector managed care reforms can be integrated, or at least linked, in a way that, from the standpoint of families who have children with special needs, the total delivery system becomes more seamless.

Theoretically, there is a great deal of compatibility between large-scale managed care and systems of care. To illustrate, the chart below depicts the goals of �4th generation� managed care as articulated by the commercial managed care industry. The edits that have been made in italics suggest the very slight tinkering that has to be done to make these goals virtually synonymous with those of systems of care.

Managed care in the public sector, of course, is not in its 4th generation, but, rather 2nd, maybe heading for 3rd. Conceptually, however, the �4th generation� concept suggests the potential for fit between large scale managed care and systems of care that are developing valuable experience in integrating care for children with special needs and their families.

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS: DEFINING THE CHALLENGE OF SERVING YOUTH WITH SED AND DD

Kathleen D. Betts, M.P.H.

Deputy Assistant Secretary

Children, Youth and Families

COORDINATED FAMILY-FOCUSED CARE

A multi-agency program serving eligible MassHealth children and their families living in Brockton, Lawrence, New Bedford, Springfield, and Worcester.

The Program: |

Coordinated Family-Focused Care (CFFC) is a program that helps to coordinate the care of children and adolescents who are at risk for out-of-home placements because of their serious emotional disturbances. The CFFC program builds on family strengths and available support systems to help children remain and function productively in the community. |

Approach: |

Drawing from the belief that families are the most important resource, CFFC develops integrated community-based treatment plans that meet the specific needs of each child and family. Key features of the program include the individual care plan, which identifies the treatment goals and the services and supports offered by CFFC, and care management services that ensure services are integrated, monitored, and evaluated. |

Services: |

CFFC provides family and children with a range of care management and support services to respond to the multiple needs identified by families, such as coordination of care, linkages with community supports, after-school programs, crisis response, individual and family therapy, medication management, and in-home and out-of-home respite care. |

Eligibility: |

A child may be eligible if he or she has a serious emotional disturbance that significantly affects functioning at home, school, or the community. The child must also be between the ages of 3 to 18 years old (the child can be up to age 22 if he or she is also receiving special education), be at risk of psychiatric hospitalization or residential care, be a MassHealth member and enrolled or eligible to be enrolled at the Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership, and live in Brockton, Lawrence, New Bedford, Springfield, or Worcester. Other eligibility criteria apply. |

Outcomes: |

Outcomes for youth participating in CFFC will be measured by the level of functioning in the community, hospitalization rates, use of residential placements, school attendance and performance, juvenile justice involvement and family, youth and state agency satisfaction. |

Oversight: |

The CFFC Steering Committee is comprised of the Division of Medical Assistance, the Department of Mental Health, the Department of Social Services, the Department of Youth Services, the Department of Education, the Executive Office of Health and Human Services, the Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership, and the Parent/Professional Advocacy League. |

Contact: |

Brockton |

To Request More Information

To ask questions or request more information about CFFC, please contact:

Suzanne Fields

Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership

286 Congress Street, 7th Floor

Phone: (617) 350-1916

Email: suzanne.fields@valueoptions.com

COMPREHENSIVE AND COORDINATED SYSTEMS OF CARE: ADDRESSING FINANCIAL CHALLENGES

Marc Cherna, M.S.W.

Director, Allegheny County Department of Human Services

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

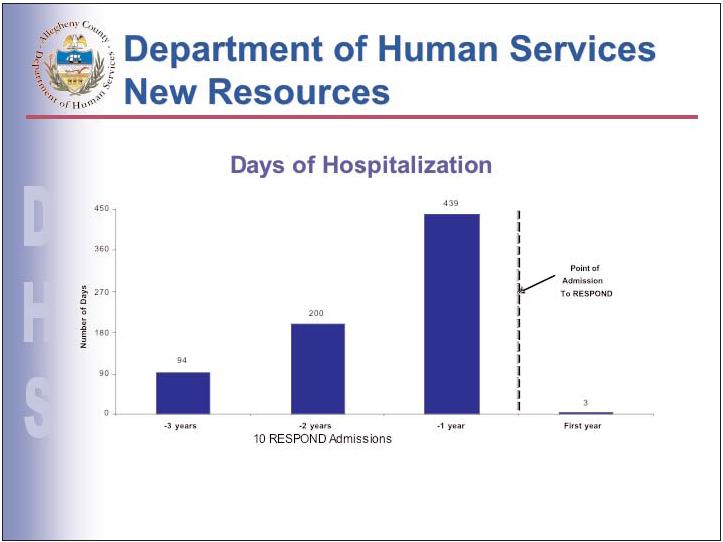

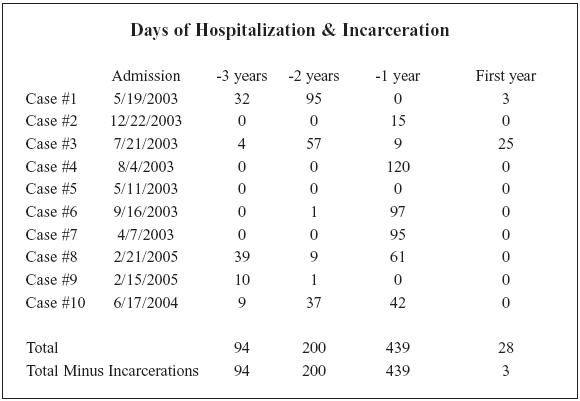

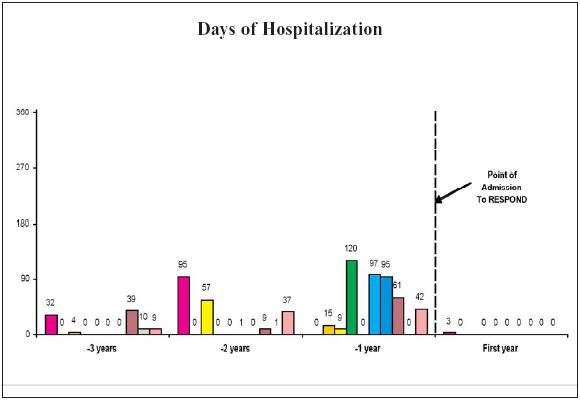

Respond Client Prior Psychiatric Hospitalizations

Case: |

ENTRY TO |

WPIC |

DISCHARGE |

# of Days |

OTHER SETTINGS |

#1 |

5/19/2003 |

7/28/2003 |

7/31/2003 |

3 |

10/02 (dates are |

#2 |

12/22/200 |

11/13/2003 |

11/21/2003 |

8 |

|

#3 |

7/21/2003 |

4/29/2004 |

5/18/2004 |

19 |

|

#4 |

8/4/2003 |

120 |

3/03 to 8/04/03 |

||

#5 |

5/11/2003 |

NO KNOWN |

|||

#6 |

9/16/2003 |

8/15/2003 |

9/16/2003 |

32 |

|

#7 |

4/7/2003 |

1/11/2003 |

1/27/2003 |

16 |

11/14/00 to 3/27/01 |

#8 |

2/21/2005 |

2/3/2002 |

2/20/2002 |

17 |

|

#9 |

2/15/2005 |

9/18/1998 |

12/16/1998 |

89 |

|

#10 |

6/17/2004 |

9/25/2001 |

10/4/2001 |

9 |

Last Revised: May 11, 2006