About This Booklet

The Lungs

Cancer Cells

Risk Factors

Screening

Symptoms

Diagnosis

Staging

Treatment

Second Opinion

Comfort Care

Nutrition

Follow-up Care

Sources of Support

The Promise of Cancer Research

National Cancer Institute Information Resources

National Cancer Institute Publications

About This Booklet

This National Cancer Institute (NCI) booklet [NIH Publication No. 07-1553]

is about cancer* that begins in the lung. It tells about diagnosis, staging, treatment, and comfort care. Learning about the medical care for people with lung cancer can help you take an active part in making choices about your own care.

This booklet has lists of questions that you may want to ask your doctor. Many people find it helpful to take a list of questions to a doctor visit. To help remember what your doctor says, you can take notes or ask whether you may use a tape recorder. You may also want to have a family member or friend with you when you talk with the doctor - to take part in the discussion, to take notes, or just to listen.

For the latest information about lung cancer, please visit our Web site at http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/lung. Or, contact our Cancer Information Service. We can answer your questions about cancer. We can send you NCI booklets and fact sheets. Call 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237) or instant message us through the LiveHelp 1 service.

*Words in italics are in the Dictionary 2. The Dictionary explains these terms. It also shows how to pronounce them.

The Lungs

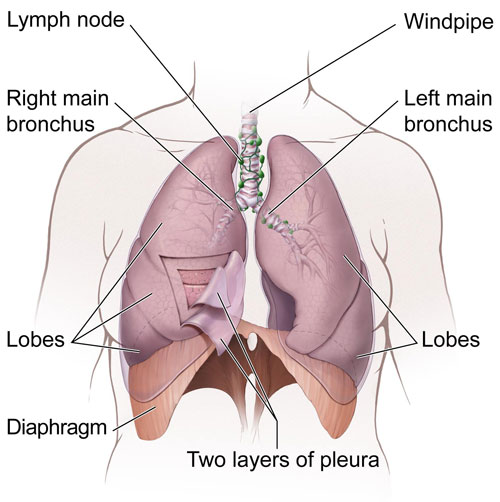

Your lungs are a pair of large organs in your chest. They are part of your respiratory system. Air enters your body through your nose or mouth. It passes through your windpipe (trachea) and through each bronchus, and goes into your lungs.

When you breathe in, your lungs expand with air. This is how your body gets oxygen.

When you breathe out, air goes out of your lungs. This is how your body gets rid of

carbon dioxide.

Your right lung has three parts (lobes). Your left lung is smaller and has two lobes.

A thin tissue (the pleura) covers the lungs and lines the inside of the chest. Between the two layers of the pleura is a very small amount of fluid (pleural fluid). Normally, this fluid does not build up.

|

| This is a picture of the lungs and nearby tissues. |

Cancer begins in cells, the building blocks that make up tissues. Tissues make up the organs of the body.

Normal, healthy cells grow and divide to form new cells as the body needs them. When normal cells grow old or become damaged, they die, and new cells take their place.

Sometimes, this orderly process goes wrong. New cells form when the body does not need them, and old or damaged cells do not die as they should. The build-up of extra cells often forms a mass of tissue called a growth or tumor.

Tumor cells can be benign (not cancer) or malignant (cancer). Benign tumor cells are usually not as harmful as malignant tumor cells:

- Benign lung tumors

- are rarely a threat to life

- usually do not need to be removed

- do not invade the tissues around them

- do not spread to other parts of the body

- Malignant lung tumors

- may be a threat to life

- may grow back after being removed

- can invade nearby tissues and organs

- can spread to other parts of the body

Cancer cells spread by breaking away from the original tumor. They enter blood vessels or lymph vessels, which branch into all the tissues of the body. The cancer cells attach to other organs and form new tumors that may damage those organs. The spread of cancer is called metastasis.

See "Staging" 3 for information about lung cancer that has spread.

Risk Factors

Doctors cannot always explain why one person develops lung cancer and another does not. However, we do know that a person with certain risk factors may be more likely than others to develop lung cancer. A risk factor is something that may increase the chance of developing a disease.

Studies have found the following risk factors for lung cancer:

-

Tobacco smoke: Tobacco smoke causes most cases of lung cancer. It's by far the most important risk factor for lung cancer. Harmful substances in smoke damage lung cells. That's why smoking cigarettes, pipes, or cigars can cause lung cancer and why secondhand smoke can cause lung cancer in nonsmokers. The more a person is exposed to smoke, the greater the risk of lung cancer. For more information, see the NCI fact sheets Quitting Smoking 4 and Secondhand Smoke 5.

-

Radon: Radon is a radioactive gas that you cannot see, smell, or taste. It forms in soil and rocks. People who work in mines may be exposed to radon. In some parts of the country, radon is found in houses. Radon damages lung cells, and people exposed to radon are at increased risk of lung cancer. The risk of lung cancer from radon is even higher for smokers. For more information, see the NCI fact sheet Radon and Cancer 6.

-

Asbestos and other substances: People who have certain jobs (such as those who work in the construction and chemical industries) have an increased risk of lung cancer. Exposure to asbestos, arsenic, chromium, nickel, soot, tar, and other substances can cause lung cancer. The risk is highest for those with years of exposure. The risk of lung cancer from these substances is even higher for smokers.

-

Air pollution: Air pollution may slightly increase the risk of lung cancer. The risk from air pollution is higher for smokers.

-

Family history of lung cancer: People with a father, mother, brother, or sister who had lung cancer may be at slightly increased risk of the disease, even if they don't smoke.

-

Personal history of lung cancer: People who have had lung cancer are at increased risk of developing a second lung tumor.

-

Age over 65: Most people are older than 65 years when diagnosed with lung cancer.

Researchers have studied other possible risk factors. For example, having certain lung diseases (such as

tuberculosis

or bronchitis) for many years may increase the risk of lung cancer. It's not yet clear whether having certain lung diseases is a risk factor for lung cancer.

People who think they may be at risk for developing lung cancer should talk to their doctor. The doctor may be able to suggest ways to reduce their risk and can plan an appropriate schedule for checkups. For people who have been treated for lung cancer, it's important to have checkups after treatment. The lung tumor may come back after treatment, or another lung tumor may develop.

|

Quitting is important for anyone who smokes tobacco -- even people who have smoked for many years. For people who already have cancer, quitting may reduce the chance of getting another cancer. Quitting also can help cancer treatments work better.

There are many ways to get help:

- Ask your doctor about medicine or nicotine replacement therapy, such as a patch, gum, lozenge, nasal spray, or inhaler. Your doctor can suggest a number of treatments that help people quit.

-

Ask your doctor to help you find local programs or trained professionals who help people stop using tobacco.

-

Call staff at NCI's Smoking Quitline (1-877-44U-QUIT) or instant message them through LiveHelp 1. They can tell you about:

- ways to quit smoking

- groups that help smokers who want to quit

- NCI publications about quitting smoking

- how to take part in a study of methods to help smokers quit

-

Go online to Smokefree.gov (http://www.smokefree.gov), a Federal Government Web site. It offers a guide to quitting smoking and a list of other resources.

|

|

Screening

Screening tests may help doctors find and treat cancer early. They have been shown to be very helpful in some cancers such as breast cancer. Currently, there is no generally accepted screening test for lung cancer. Several methods of detecting lung cancer have been studied as possible screening tests. The methods under study include tests of sputum (mucus brought up from the lungs by coughing), chest x-rays, or spiral (helical) CT scans. You can read more about these tests in the Diagnosis 7 section.

However, screening tests have risks. For example, an abnormal x-ray result could lead to other procedures (such as surgery to check for cancer cells), but a person with an abnormal test result might not have lung cancer. Studies so far have not shown that screening tests lower the number of deaths from lung cancer. See "The Promise of Cancer Research" 8 section for information about research studies of screening tests for lung cancer.

You may want to talk with your doctor about your own risk factors and the possible benefits and harms of being screened for lung cancer. Like many other medical decisions, the decision to be screened is a personal one. Your decision may be easier after learning the pros and cons of screening.

Symptoms

Early lung cancer often does not cause symptoms. But as the cancer grows, common symptoms may include:

- a cough that gets worse or does not go away

- breathing trouble, such as shortness of breath

- constant chest pain

- coughing up blood

- a hoarse voice

- frequent lung infections, such as pneumonia

- feeling very tired all the time

- weight loss with no known cause

Most often these symptoms are not due to cancer. Other health problems can cause some of these symptoms. Anyone with such symptoms should see a doctor to be diagnosed and treated as early as possible.

Diagnosis

If you have a symptom that suggests lung cancer, your doctor must find out whether it's from cancer or something else. Your doctor may ask about your personal and family medical history. Your doctor

may order blood tests, and you may have one or more of the following tests:

-

Physical exam: Your doctor checks for general signs of health, listens to your breathing, and checks for fluid in the lungs. Your doctor may feel for swollen lymph nodes and a swollen liver.

-

Chest x-ray: X-ray pictures of your chest may show tumors or abnormal fluid.

-

CT scan: Doctors often use CT scans to take pictures of tissue inside the chest. An x-ray machine linked to a computer takes several pictures. For a spiral CT scan, the CT scanner rotates around you as you lie on a table. The table passes through the center of the scanner. The pictures may show a tumor, abnormal fluid, or swollen lymph nodes.

The only sure way to know if lung cancer is present is for a

pathologist

to check samples of cells or tissue. The pathologist studies the sample under a microscope and performs other tests. There are many ways to collect samples.

Your doctor may order one or more of the following tests to collect samples:

- Sputum cytology: Thick fluid (sputum) is coughed up from the lungs. The lab checks samples of sputum for cancer cells.

-

Thoracentesis: The doctor uses a long needle to remove fluid (pleural fluid) from the chest. The lab checks the fluid for cancer cells.

-

Bronchoscopy: The doctor inserts a thin, lighted tube (a bronchoscope) through the nose or mouth into the lung. This allows an exam of the lungs and the air passages that lead to them. The doctor may take a sample of cells with a needle, brush, or other tool. The doctor also may wash the area with water to collect cells in the water.

-

Fine-needle aspiration: The doctor uses a thin needle to remove tissue or fluid from the lung or lymph node. Sometimes the doctor uses a CT scan or other imaging method to guide the needle to a lung tumor or lymph node.

-

Thoracoscopy: The surgeon makes several small incisions in your chest and back. The surgeon looks at the lungs and nearby tissues with a thin, lighted tube. If an abnormal area is seen, a

biopsy

to check for cancer cells may be needed.

-

Thoracotomy: The surgeon opens the chest with a long incision. Lymph nodes and other tissue may be removed.

-

Mediastinoscopy: The surgeon makes an incision at the top of the breastbone. A thin, lighted tube is used to see inside the chest. The surgeon may take tissue and lymph node samples.

|

You may want to ask these questions before the doctor takes a sample of tissue:

- Which procedure do you recommend? How will the tissue be removed?

- Will I have to stay in the hospital? If so, for how long?

- Will I have to do anything to prepare for it?

- How long will it take? Will I be awake? Will it hurt?

- Are there any risks? What is the chance that the procedure will make my lung collapse? What are the chances of infection or bleeding after the procedure?

- How long will it take me to recover?

- How soon will I know the results? Who will explain them to me?

- If I do have cancer, who will talk to me about next steps? When?

|

The pathologist checks the sputum, pleural fluid, tissue, or other samples for cancer cells. If cancer is found, the pathologist reports the type. The types of lung cancer are treated differently. The most common types are named for how the lung cancer cells look under a microscope:

-

Small cell lung cancer: About 13 percent of lung cancers are small cell lung cancers. This type tends to spread quickly.

-

Non-small cell lung cancer: Most lung cancers (about 87 percent) are non-small cell lung cancers. This type spreads more slowly than small cell lung cancer.

Staging

To plan the best treatment, your doctor needs to know the type of lung cancer and the extent (stage) of the disease. Staging is a careful attempt to find out whether the cancer has spread, and if so, to what parts of the body. Lung cancer spreads most often to the lymph nodes, brain, bones, liver, and adrenal glands.

When cancer spreads from its original place to another part of the body, the new tumor has the same kind of cancer cells and the same name as the original cancer. For example, if lung cancer spreads to the liver, the cancer cells in the liver are actually lung cancer cells. The disease is metastatic lung cancer, not liver cancer. For that reason, it's treated as lung cancer, not liver cancer. Doctors call the new tumor "distant" or metastatic disease.

Staging may involve blood tests and other tests:

-

CT scan: CT scans may show cancer that has spread to your liver, adrenal glands, brain, or other organs. You may receive contrast material by mouth and by injection into your arm or hand. The contrast material helps these tissues show up more clearly. If a tumor shows up on the CT scan, your doctor may order a biopsy to look for lung cancer cells.

-

Bone scan: A bone scan may show cancer that has spread to your bones. You receive an injection of a small amount of a radioactive substance. It travels through your blood and collects in your bones. A machine called a scanner detects and measures the radiation. The scanner makes pictures of your bones on a computer screen or on film.

-

MRI: Your doctor may order MRI pictures of your brain, bones, or other tissues. MRI uses a powerful magnet linked to a computer. It makes detailed pictures of tissue on a computer screen or film.

-

PET scan: Your doctor uses a PET scan to find cancer that has spread. You receive an injection of a small amount of radioactive sugar. A machine makes computerized pictures of the sugar being used by cells in the body. Cancer cells use sugar faster than normal cells, and areas with cancer look brighter on the pictures.

Doctors describe small cell lung cancer using two stages:

- Limited stage: Cancer is found only in one lung and its nearby tissues.

- Extensive stage: Cancer is found in tissues of the chest outside of the lung in which it began. Or cancer is found in distant organs.

The treatment options are different for limited and extensive stage small cell lung cancer. See the Treatment 9 section for information about treatment choices.

Doctors describe non-small cell lung cancer based on the size of the lung tumor and whether cancer has spread to the lymph nodes or other tissues:

-

Occult stage: Lung cancer cells are found in sputum or in a sample of water collected during bronchoscopy, but a tumor cannot be seen in the lung.

-

Stage 0: Cancer cells are found only in the innermost lining of the lung. The tumor has not grown through this lining. A Stage 0 tumor is also called carcinoma in situ. The tumor is not an invasive cancer.

-

Stage IA: The lung tumor is an invasive cancer. It has grown through the innermost lining of the lung into deeper lung tissue. The tumor is no more than 3 centimeters across (less than 1 ¼ inches). It is surrounded by normal tissue and the tumor does not invade the bronchus. Cancer cells are not found in nearby lymph nodes.

-

Stage IB: The tumor is larger or has grown deeper, but cancer cells are not found in nearby lymph nodes. The lung tumor is one of the following (see the picture of the main bronchus and pleura 10):

- The tumor is more than 3 centimeters across.

- It has grown into the main bronchus.

- It has grown through the lung into the pleura.

-

Stage IIA: The lung tumor is no more than 3 centimeters across. Cancer cells are found in nearby lymph nodes.

-

Stage IIB: The tumor is one of the following:

- Cancer cells are not found in nearby lymph nodes, but the tumor has invaded the chest wall, diaphragm, pleura, main bronchus, or tissue that surrounds the heart (see the picture of the diaphragm 10).

- Cancer cells are found in nearby lymph nodes, and one of the following:

- The tumor is more than 3 centimeters across.

- It has grown into the main bronchus.

- It has grown through the lung into the pleura.

-

Stage IIIA: The tumor may be any size. Cancer cells are found in the lymph nodes near the lungs and bronchi, and in the lymph nodes between the lungs but on the same side of the chest as the lung tumor.

-

Stage IIIB: The tumor may be any size. Cancer cells are found on the opposite side of the chest from the lung tumor or in the neck. The tumor may have invaded nearby organs, such as the heart, esophagus, or trachea. More than one malignant growth may be found within the same lobe of the lung. The doctor may find cancer cells in the pleural fluid.

-

Stage IV: Malignant growths may be found in more than one lobe of the same lung or in the other lung. Or cancer cells may be found in other parts of the body, such as the brain, adrenal gland, liver, or bone.

You can find pictures of the stages of lung cancer and information about their treatment choices on the NCI Web site (http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/lung). Or you can call the Cancer Information Service at 1-800-4-CANCER.

Treatment

Your doctor may refer you to a specialist who has experience treating lung cancer, or you may ask for a referral. You may have a team of specialists. Specialists who treat lung cancer include thoracic (chest) surgeons, thoracic surgical oncologists, medical oncologists, and

radiation oncologists. Your health care team may also include a

pulmonologist

(a lung specialist), a

respiratory therapist, an oncology nurse, and a registered dietitian.

Lung cancer is hard to control with current treatments. For that reason, many doctors encourage patients with this disease to consider taking part in a clinical trial. Clinical trials are an important option for people with all stages of lung cancer. See "The Promise of Cancer Research." 8

The choice of treatment depends mainly on the type of lung cancer and its stage. People with lung cancer may have surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, targeted therapy, or a combination of treatments.

People with limited stage small cell lung cancer usually have radiation therapy and chemotherapy. For a very small lung tumor, a person may have surgery and chemotherapy. Most people with extensive stage small cell lung cancer are treated with chemotherapy only.

People with non-small cell lung cancer may have surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination of treatments. The treatment choices are different for each stage. Some people with advanced cancer receive targeted therapy.

Cancer treatment is either local therapy or systemic therapy:

- Local therapy: Surgery and radiation therapy are local therapies. They remove or destroy cancer in the chest. When lung cancer has spread to other parts of the body, local therapy may be used to control the disease in those specific areas. For example, lung cancer that spreads to the brain may be controlled with radiation therapy to the head.

- Systemic therapy: Chemotherapy and targeted therapy are systemic therapies. The drugs enter the bloodstream and destroy or control cancer throughout the body.

Your doctor can describe your treatment choices and the expected results. You may want to know about side effects and how treatment may change your normal activities. Because cancer treatments often damage healthy cells and tissues, side effects are common. Side effects depend mainly on the type and extent of the treatment. Side effects may not be the same for each person, and they may change from one treatment session to the next. Before treatment starts, your health care team will explain possible side effects and suggest ways to help you manage them.

You and your doctor can work together to develop a treatment plan that meets your medical and personal needs.

|

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before your treatment begins:

- What is the stage of my disease? Has the cancer spread from the lung? If so, to where?

- What are my treatment choices? Which do you recommend for me? Why?

- Will I have more than one kind of treatment?

- What are the expected benefits of each kind of treatment?

- What are the risks and possible side effects of each treatment? What can we do to control the side effects?

- What can I do to prepare for treatment?

- Will I need to stay in the hospital? If so, for how long?

- What is the treatment likely to cost? Will my insurance cover the cost?

- How will treatment affect my normal activities?

- Would a clinical trial be right for me?

- How often should I have checkups after treatment?

|

Surgery for lung cancer removes the tissue that contains the tumor. The surgeon also removes nearby lymph nodes.

The surgeon removes part or all of the lung:

- A small part of the lung (wedge resection or

segmentectomy): The surgeon removes the tumor and a small part of the lung.

- A lobe of the lung (lobectomy or

sleeve lobectomy): The surgeon removes a lobe of the lung. This is the most common surgery for lung cancer.

- All of the lung (pneumonectomy): The surgeon removes the entire lung.

After lung surgery, air and fluid collect in the chest. A chest tube allows the fluid to drain. Also, a nurse or respiratory therapist will teach you coughing and breathing exercises. You'll need to do the exercises several times a day.

The time it takes to heal after surgery is different for everyone. Your hospital stay may be a week or longer. It may be several weeks before you return to normal activities.

Medicine can help control your pain after surgery. Before surgery, you should discuss the plan for pain relief with your doctor or nurse. After surgery, your doctor can adjust the plan if you need more pain relief.

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before having surgery:

- What kind of surgery do you suggest for me?

- How will I feel after surgery?

- If I have pain, how will it be controlled?

- How long will I be in the hospital?

- Will I have any lasting side effects?

- When can I get back to my normal activities?

|

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) uses high-energy rays to kill cancer cells. It affects cells only in the treated area.

You may receive external radiation. This is the most common type of radiation therapy for lung cancer. The radiation comes from a large machine outside your body. Most people go to a hospital or clinic for treatment. Treatments are usually 5 days a week for several weeks.

Another type of radiation therapy is internal radiation (brachytherapy). Internal radiation is seldom used for people with lung cancer. The radiation comes from a seed, wire, or another device put inside your body.

The side effects depend mainly on the type of radiation therapy, the dose of radiation, and the part of your body that is treated. External radiation therapy to the chest may harm the esophagus, causing problems with swallowing. You may also feel very tired. In addition, your skin in the treated area may become red, dry, and tender. After internal radiation therapy, a person may cough up small amounts of blood.

Your doctor can suggest ways to ease these problems. You may find it helpful to read NCI's booklet Radiation Therapy and You 11.

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before having radiation therapy:

- Why do I need this treatment?

- What kind of radiation therapy do you suggest for me?

- When will the treatments begin? When will they end?

- How will I feel during treatment?

- How will we know if the radiation treatment is working?

- Are there any lasting side effects?

|

Chemotherapy uses anticancer drugs to kill cancer cells. The drugs enter the bloodstream and can affect cancer cells all over the body.

Usually, more than one drug is given. Anticancer drugs for lung cancer are usually given through a vein (intravenous). Some anticancer drugs can be taken by mouth.

Chemotherapy is given in cycles. You have a rest period after each treatment period. The length of the rest period and the number of cycles depend on the anticancer drugs used.

You may have your treatment in a clinic, at the doctor's office, or at home. Some people may need to stay in the hospital for treatment.

The side effects depend mainly on which drugs are given and how much. The drugs can harm normal cells that divide rapidly:

- Blood cells: When chemotherapy lowers your levels of healthy blood cells, you're more likely to get infections, bruise or bleed easily, and feel very weak and tired. Your health care team gives you blood tests to check for low levels of blood cells. If the levels are low, there are medicines that can help your body make new blood cells.

- Cells in hair roots: Chemotherapy may cause hair loss. Your hair will grow back after treatment ends, but it may be somewhat different in color and texture.

- Cells that line the digestive tract: Chemotherapy can cause poor appetite, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, or mouth and lip sores. Ask your health care team about treatments that help with these problems.

Some drugs for lung cancer can cause hearing loss, joint pain, and tingling or numbness in your hands and feet. These side effects usually go away after treatment ends.

When radiation therapy and chemotherapy are given at the same time, the side effects may be worse.

You may find it helpful to read NCI's booklet Chemotherapy and You 12.

Targeted therapy uses drugs to block the growth and spread of cancer cells. The drugs enter the bloodstream and can affect cancer cells all over the body. Some people with non-small cell lung cancer that has spread receive targeted therapy.

There are two kinds of targeted therapy for lung cancer:

- One kind is given through a vein (intravenous) at the doctor's office, hospital, or clinic. It's given at the same time as chemotherapy. The side effects may include bleeding, coughing up blood, a rash, high blood pressure, abdominal pain, vomiting, or diarrhea.

- Another kind of targeted therapy is taken by mouth. It isn't given with chemotherapy. The side effects may include rash, diarrhea, and shortness of breath.

During treatment, your health care team will watch for signs of problems. Side effects usually go away after treatment ends.

You may find it helpful to read the NCI fact sheet Targeted Cancer Therapies 13. It tells about the types of targeted therapies and how they work.

|

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before having chemotherapy or targeted therapy:

- What drugs will I have? What are the expected benefits?

- When will treatment start? When will it end? How often will I have treatments?

- Where will I go for treatment?

- What can I do to take care of myself during treatment?

- How will we know the treatment is working?

- What side effects should I tell you about? Can I prevent or treat any of these side effects?

- Will there be lasting side effects?

|

Second Opinion

Before starting treatment, you might want a second opinion about your diagnosis and treatment plan. Many insurance companies cover a second opinion if you or your doctor requests it.

It may take some time and effort to gather your medical records and see another doctor. In most cases, a brief delay in starting treatment will not make treatment less effective. To make sure, you should discuss this delay with your doctor. Sometimes people with lung cancer need treatment right away. For example, a doctor may advise a person with small cell lung cancer not to delay treatment more than a week or two.

There are many ways to find a doctor for a second opinion. You can ask your doctor, a local or state medical society, a nearby hospital, or a medical school for names of specialists. Also, your nearest cancer center can tell you about doctors who work there.

You may want to read NCI's fact sheet How To Find a Doctor or Treatment Facility If You Have Cancer 14.

Comfort Care

Lung cancer and its treatment can lead to other health problems. You may need comfort care to prevent or control these problems.

Comfort care is available both during and after treatment. It can improve your quality of life.

Your health care team can tell you more about the following problems and how to control them:

-

Pain: Your doctor or a pain control specialist can suggest ways to relieve or reduce pain. More information about pain control can be found in the NCI booklet Pain Control 15.

-

Shortness of breath or trouble breathing: People with lung cancer often have trouble breathing. Your doctor may refer you to a lung specialist or respiratory therapist. Some people are helped by

oxygen therapy, photodynamic therapy, laser surgery, cryotherapy, or stents.

-

Fluid in or around lungs: Advanced cancer can cause fluid to collect in or around the lungs. The fluid can make it hard to breathe. Your health care team can remove fluid when it builds up. In some cases, a procedure can be done that may prevent fluid from building up again. Some people may need chest tubes to drain the fluid.

-

Pneumonia: You may have chest x-rays to check for lung infections. Your doctor can treat infections.

-

Cancer that spreads to the brain: Lung cancer can spread to the brain. The symptoms may include headache, seizures, trouble walking, and problems with balance. Medicine to relieve swelling, radiation therapy, or sometimes surgery can help.

People with small cell lung cancer may receive radiation therapy to the brain to try to prevent brain tumors from forming. This is called prophylactic cranial irradiation.

-

Cancer that spreads to the bone: Lung cancer that spreads to the bone can be painful and can weaken bones. You can ask for pain medicine, and the doctor may suggest external radiation therapy. Your doctor also may give you drugs to help lower your risk of breaking a bone.

-

Sadness and other feelings: It's normal to feel sad, anxious, or confused after a diagnosis of a serious illness. Some people find it helpful to talk about their feelings. See the "Sources of Support" 16 section for more information.

You can get information about comfort care on NCI's Web site at http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/coping and from NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-4-CANCER or LiveHelp 1.

Nutrition

It's important for you to take care of yourself by eating well. You need the right amount of calories to maintain a good weight. You also need enough protein to keep up your strength. Eating well may help you feel better and have more energy.

Sometimes, especially during or soon after treatment, you may not feel like eating. You may be uncomfortable or tired. You may find that foods don't taste as good as they used to. In addition, the side effects of treatment (such as poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, or mouth sores) can make it hard to eat well.

Your doctor, a registered dietitian, or another health care provider can suggest ways to deal with these problems. Also, the NCI booklet Eating Hints for Cancer Patients 17 has many useful ideas and recipes.

Follow-up Care

You'll need regular checkups after treatment for lung cancer. Even when there are no longer any signs of cancer, the disease sometimes returns because undetected cancer cells remained somewhere in your body after treatment.

Checkups help ensure that any changes in your health are noted and treated if needed. Checkups may include a physical exam, blood tests, chest x-rays, CT scans, and bronchoscopy.

If you have any health problems between checkups, contact your doctor.

You may want to read the NCI booklet Facing Forward Series: Life After Cancer Treatment 18. It answers questions about follow-up care and other concerns.

Sources of Support

Learning you have lung cancer can change your life and the lives of those close to you. These changes can be hard to handle. It's normal for you, your family, and your friends to have many different and sometimes confusing feelings.

You may worry about caring for your family, keeping your job, or continuing daily activities. Concerns about treatments and managing side effects, hospital stays, and medical bills are also common.

Because most people who get lung cancer were smokers, you may feel like doctors and other people assume that you are or were a smoker (even if you weren't). You may feel as though you're responsible for getting cancer (or that others blame you). It's normal for anyone coping with a serious illness to feel fear, guilt, anger, or sadness. It may help to share your feelings with family, friends, a member of your health care team, or another person with cancer.

Here's where you can go for support:

- Doctors, nurses, and other members of your health care team can answer many of your questions.

- Social workers, counselors, or members of the clergy can be helpful if you want to talk about your feelings or concerns. Often, social workers can suggest resources for financial aid, transportation, home care, or emotional support.

- Support groups also can help. In these groups, patients or their family members meet with other patients or their families to share what they have learned about coping with the disease and the effects of treatment. Groups may offer support in person, over the telephone, or on the Internet. You may want to talk with a member of your health care team about finding a support group.

- Information specialists at 1-800-4-CANCER and at LiveHelp 1 can help you locate programs, services, and publications.

For the names of organizations offering support, you may want to search the NCI database "National Organizations That Offer Services to People With Cancer and Their Families." 19

For tips on coping, you may want to read the NCI booklet Taking Time: Support for People With Cancer 20.

The Promise of Cancer Research

Doctors all over the country are conducting many types of clinical trials (research studies in which people volunteer to take part). Clinical trials are designed to answer important questions and to find out whether new approaches are safe and effective.

Research already has led to advances that have helped people live longer, and research continues. Researchers are studying methods of preventing lung cancer and ways to screen for it. They are also trying to find better ways to treat it.

-

Prevention: NCI is sponsoring studies of substances that may help prevent the development of lung cancer. For example, people with early non-small cell lung cancer are taking selenium to learn whether it can help prevent the growth of new lung tumors.

-

Screening tests: Doctors are studying whether screening tests can detect lung cancer early and reduce a person's chance of dying from it. The NCI is sponsoring large research studies of chest x-rays and spiral CT scans for lung cancer screening. So far, chest x-rays and spiral CT scans have not been shown to reduce a person's chance of dying from lung cancer.

- Treatment: Researchers are studying many types of treatment and their combinations.

- Surgery: Surgeons are studying the removal of less lung tissue and using internal radiation therapy (brachytherapy) to kill cancer cells that remain.

- Chemotherapy: Researchers are testing new anticancer drugs and new combinations of drugs. They're also combining chemotherapy with radiation therapy.

- Targeted therapy: Doctors are combining new targeted therapies with chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

- Radiation therapy: Researchers are studying whether radiation therapy to the brain can prevent brain tumors from forming among people with non-small cell lung cancer.

If you're interested in being part of a clinical trial, talk with your

doctor. People who join clinical trials make an important contribution

by helping doctors learn more about lung cancer and how to control it.

Although clinical trials may pose some risks, researchers do all they

can to protect their patients.

NCI's Web site includes a section on clinical trials at

http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials. It has general information about

clinical trials as well as detailed information about current lung

cancer studies. Information specialists at 1-800-4-CANCER or at

LiveHelp can answer questions and provide information about clinical

trials.

For information about taking part in treatment studies, you may want to

read the NCI booklet Taking Part in Cancer Treatment Research Studies 21.

National Cancer Institute Information Resources

You may want more information for yourself, your family, and your doctor. The following NCI services are available to help you.

NCI's Cancer Information Service (CIS) provides accurate, up-to-date information about cancer to patients and their families, health professionals, and the general public. Information specialists translate the latest scientific information into plain language and respond in English or Spanish. Calls to the CIS are confidential and free.

| Telephone: | 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237) |

| TTY: | 1-800-332-8615 |

NCI's Web site provides information from numerous NCI sources. It offers current information about cancer prevention, screening, diagnosis, treatment, genetics, supportive care, and ongoing clinical trials. It has information about NCI's research programs, funding opportunities, and cancer statistics.

If you are unable to find what you need on the Web site, contact NCI staff. Use the online contact form at http://www.cancer.gov/contact or send an email to cancergovstaff@mail.nih.gov.

Also, Information specialists provide live, online assistance through

LiveHelp 1 at http://www.cancer.gov/help.

National Cancer Institute Publications

NCI provides publications about cancer, including the booklets and fact sheets mentioned in this booklet. Many are available in both English and Spanish.

You can order them by telephone, on the Internet, or by mail. You can also read them online and print your own copy.

-

By telephone: People in the United States and its territories may order these and other NCI publications by calling the NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-4-CANCER.

-

On the Internet: Many NCI publications can be viewed, downloaded, and ordered from http://www.cancer.gov/publications on the Internet. People in the United States and its territories may use this Web site to order printed copies. This Web site also explains how people outside the United States can mail or fax their requests for NCI booklets.

- By mail: NCI publications can be ordered by writing to the address below:

|

Publications Ordering Service

National Cancer Institute

Suite 3035A

6116 Executive Boulevard, MSC 8322

Bethesda, MD 20892-8322 |

Cancer Treatment

Chemotherapy and You 12(also available in Spanish: La quimioterapia y usted)

Radiation Therapy and You 11 (also available in Spanish: La radioterapia y usted)

Helping Yourself During Chemotherapy: 4 Steps for Patients 22

How To Find a Doctor or Treatment Facility If You Have Cancer 14 (also available in Spanish: Cómo encontrar a un doctor o un establecimiento de tratamiento si usted tiene cáncer 23)

Targeted Cancer Therapies: Questions and Answers 13

Photodynamic Therapy for Cancer: Questions and Answers 24

Living With Cancer

Eating Hints for Cancer Patients 17(also available in Spanish: Consejos de alimentación para pacientes con cáncer)

Pain Control 15 (also available in Spanish: Control del dolor)

Coping With Advanced Cancer 25

Facing Forward Series: Life After Cancer Treatment 18(also available in Spanish: Siga adelante: la vida después del tratamiento del cáncer 26)

Facing Forward Series: Ways You Can Make a Difference in Cancer 27

Taking Time: Support for People with Cancer 20

When Cancer Returns 28

National Organizations That Offer Services to People With Cancer and Their Families 19 (also available in Spanish: Organizaciones nacionales que brindan servicios a las personas con cáncer y a sus familias)

Clinical Trials

Taking Part in Cancer Treatment Research Studies 21

Complementary Medicine

Thinking about Complementary & Alternative Medicine: A guide for people with cancer 29

Risk Factors

Secondhand Smoke: Questions and Answers 5

Radon and Cancer: Questions and Answers 6

Quitting Smoking

Clearing the Air: Quit Smoking Today 30

You Can Quit Smoking 31

Quitting Smoking: Why to Quit and How to Get Help 4

The Truth About "Light" Cigarettes 32

Caregivers

When Someone You Love Is Being Treated for Cancer: Support for Caregivers 33

When Someone You Love Has Advanced Cancer: Support for Caregivers 34

Facing Forward: When Someone You Love Has Completed Cancer Treatment 35

|