Introduction

The Liver

Understanding Cancer

Liver Cancer: Who's at Risk?

Symptoms

Diagnosis

Staging

Treatment

Getting a Second Opinion

Treatment Choices

Localized resectable cancer

Localized unresectable cancer

Advanced cancer

Recurrent cancer

Side Effects of Treatment

Pain Control

Nutrition

Continuing Care

Support for People with Liver Cancer

The Promise of Cancer Research

National Cancer Institute Booklets

National Cancer Institute Information Resources

Introduction

This National Cancer Institute (NCI) booklet (NIH Publication No. 01-5009) has important information about cancer* that begins in the liver. It discusses possible causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of liver cancer. It also has information to help patients cope with this disease.

Information specialists at the NCI's Cancer Information Service 1 at 1-800-4-CANCER can help people with questions about cancer and can send NCI publications. Also, many NCI publications are on the Internet at http://www.cancer.gov/publications. People in the United States and its territories may use this Web site to order publications. This Web site also explains how people outside the United States can mail or fax their requests for NCI publications.

|

Primary and Secondary Cancers

Cancer that begins in the liver is called primary liver cancer. In the United States, this type of cancer is uncommon. However, it is common for cancer to spread to the liver from the colon, lungs, breasts, or other parts of the body. When this happens, the disease is not liver cancer. The cancer in the liver is a secondary cancer. It is named for the organ or the tissue in which it began.

This booklet is only about cancer that begins in the liver. It is not about cancer that spreads to the liver from other parts of the body.

|

*Words that may be new to readers are in italics. The "Dictionary 2" gives definitions of these terms. Some words in the "Dictionary" have a "sounds-like" spelling to show how to pronounce them.

The Liver

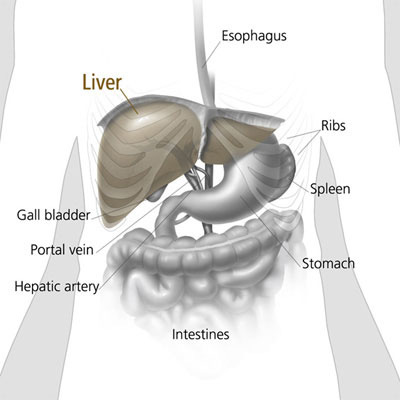

The liver is the largest organ in the body. It is found behind the ribs on the right side of the abdomen. The liver has two parts, a right lobe and a smaller left lobe.

The liver has many important functions that keep a person healthy. It removes harmful material from the blood. It makes enzymes and bile that help digest food. It also converts food into substances needed for life and growth.

The liver gets its supply of blood from two vessels. Most of its blood comes from the hepatic portal vein. The rest comes from the hepatic artery.

This picture shows the liver and nearby organs.

|

Understanding Cancer

Cancer is a group of many related diseases. All cancers begin in cells, the body's basic unit of life. Cells make up tissues, and tissues make up the organs of the body.

Normally, cells grow and divide to form new cells as the body needs them. When cells grow old and die, new cells take their place.

Sometimes, this orderly process goes wrong. New cells form when the body does not need them, or old cells do not die when they should. These extra cells can form a mass of tissue called a growth or tumor. Tumors can be benign or malignant:

Benign tumors are not cancer. Usually, doctors can remove them. In most cases, benign tumors do not come back after they are removed. Cells from benign tumors do not spread to tissues around them or to other parts of the body. Most important, benign tumors are rarely a threat to life. Malignant tumors are cancer. They are generally more serious and may be life threatening. Cancer cells can invade and damage nearby tissues and organs. Also, cancer cells can break away from a malignant tumor and enter the bloodstream or the lymphatic system. That is how cancer cells spread from the original cancer (the primary tumor) to form new tumors (secondary tumors) in other organs. The spread of cancer is called metastasis. Different types of cancer tend to spread to different parts of the body.

Most primary liver cancers begin in hepatocytes (liver cells). This type of cancer is called hepatocellular carcinoma or malignant hepatoma.

Children may develop childhood hepatocellular carcinoma or hepatoblastoma. This booklet does not deal with childhood liver cancer. Material is available at http://www.cancer.gov. Also, the Cancer Information Service (1-800-4-CANCER) can provide information about liver cancer in children.

When liver cancer spreads (metastasizes) outside the liver, the cancer cells tend to spread to nearby lymph nodes and to the bones and lungs. When this happens, the new tumor has the same kind of abnormal cells as the primary tumor in the liver. For example, if liver cancer spreads to the bones, the cancer cells in the bones are actually liver cancer cells. The disease is metastatic liver cancer, not bone cancer. It is treated as liver cancer, not bone cancer. Doctors sometimes call the new tumor "distant" disease.

Similarly, cancer that spreads to the liver from another part of the body is different from primary liver cancer. The cancer cells in the liver are like the cells in the original tumor. When cancer cells spread to the liver from another organ (such as the colon, lung, or breast), doctors may call the tumor in the liver a secondary tumor. In the United States, secondary tumors in the liver are far more common than primary tumors.

Liver Cancer: Who's at Risk?

Researchers in hospitals and medical centers around the world are working to learn more about what causes liver cancer. At this time, no one knows its exact causes. However, scientists have found that people with certain risk factors are more likely than others to develop liver cancer. A risk factor is anything that increases a person's chance of developing a disease.

Studies have shown the following risk factors:

Chronic liver infection (hepatitis) -- Certain viruses can infect the liver. The infection may be chronic. (It may not go away.) The most important risk factor for liver cancer is a chronic infection with the hepatitis B virus or the hepatitis C virus. These viruses can be passed from person to person through blood (such as by sharing needles) or sexual contact. An infant may catch these viruses from an infected mother. Liver cancer can develop after many years of infection with the virus.

These infections may not cause symptoms, but blood tests can show whether either virus is present. If so, the doctor may suggest treatment. Also, the doctor may discuss ways of avoiding infecting other people.

In people who are not already infected with hepatitis B virus, hepatitis B vaccine can prevent chronic hepatitis B infection and can protect against liver cancer. Researchers are now working to develop a vaccine to prevent hepatitis C infection.

Cirrhosis -- Cirrhosis is a disease that develops when liver cells are damaged and replaced with scar tissue. Cirrhosis may be caused by alcohol abuse, certain drugs and other chemicals, and certain viruses or parasites. About 5 percent of people with cirrhosis develop liver cancer. Aflatoxin -- Liver cancer can be caused by aflatoxin, a harmful substance made by certain types of mold. Aflatoxin can form on peanuts, corn, and other nuts and grains. In Asia and Africa, aflatoxin contamination is a problem. However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not allow the sale of foods that have high levels of aflatoxin. Being male -- Men are twice as likely as women to get liver cancer. Family history -- People who have family members with liver cancer may be more likely to get the disease. Age -- In the United States, liver cancer occurs more often in people over age 60 than in younger people.

The more risk factors a person has, the greater the chance that liver cancer will develop. However, many people with known risk factors for liver cancer do not develop the disease.

People who think they may be at risk for liver cancer should discuss this concern with their doctor. The doctor may plan a schedule for checkups.

Symptoms

Liver cancer is sometimes called a "silent disease" because in an early stage it often does not cause symptoms. But, as the cancer grows, symptoms may include:

Pain in the upper abdomen on the right side; the pain may extend to the back and shoulder Swollen abdomen (bloating) Weight loss Loss of appetite and feelings of fullness Weakness or feeling very tired Nausea and vomiting Yellow skin and eyes, and dark urine from jaundice Fever

These symptoms are not sure signs of liver cancer. Other liver diseases and other health problems can also cause these symptoms. Anyone with these symptoms should see a doctor as soon as possible. Only a doctor can diagnose and treat the problem.

Diagnosis

If a patient has symptoms that suggest liver cancer, the doctor performs one or more of the following procedures:

Physical exam -- The doctor feels the abdomen to check the liver, spleen, and nearby organs for any lumps or changes in their shape or size. The doctor also checks for ascites, an abnormal buildup of fluid in the abdomen. The doctor may examine the skin and eyes for signs of jaundice. Blood tests -- Many blood tests may be used to check for liver problems. One blood test detects alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). High AFP levels could be a sign of liver cancer. Other blood tests can show how well the liver is working. CT scan -- An x-ray machine linked to a computer takes a series of detailed pictures of the liver and other organs and blood vessels in the abdomen. The patient may receive an injection of a special dye so the liver shows up clearly in the pictures. From the CT scan, the doctor may see tumors in the liver or elsewhere in the abdomen. Ultrasound test -- The ultrasound device uses sound waves that cannot be heard by humans. The sound waves produce a pattern of echoes as they bounce off internal organs. The echoes create a picture (sonogram) of the liver and other organs in the abdomen. Tumors may produce echoes that are different from the echoes made by healthy tissues. MRI -- A powerful magnet linked to a computer is used to make detailed pictures of areas inside the body. These pictures are viewed on a monitor and can also be printed. Angiogram -- For an angiogram, the patient may be in the hospital and may have anesthesia. The doctor injects dye into an artery so that the blood vessels in the liver show up on an x-ray. The angiogram can reveal a tumor in the liver. Biopsy -- In some cases, the doctor may remove a sample of tissue. A pathologist uses a microscope to look for cancer cells in the tissue. The doctor may obtain tissue in several ways. One way is by inserting a thin needle into the liver to remove a small amount of tissue. This is called fine-needle aspiration. The doctor may use CT or ultrasound to guide the needle. Sometimes the doctor obtains a sample of tissue with a thick needle (core biopsy) or by inserting a thin, lighted tube (laparoscope) into a small incision in the abdomen. Another way is to remove tissue during an operation.

A patient who needs to have a biopsy may want to ask the doctor some of the following questions:

Why do I need a biopsy? How will the biopsy affect my treatment plan? What kind of biopsy will I have? How long will it take? Will I be awake? Will it hurt? Is there a risk that the biopsy procedure will cause the cancer to spread? What are the chances of infection or bleeding after the biopsy? Are there any other risks? How soon will I know the results? If I do have cancer, who will talk with me about treatment? When?

|

Staging

If liver cancer is diagnosed, the doctor needs to know the stage, or extent, of the disease to plan the best treatment. Staging is an attempt to find out the size of the tumor, whether the disease has spread, and if so, to what parts of the body. Careful staging shows whether the tumor can be removed with surgery. This is very important because most liver cancers cannot be removed with surgery.

The doctor may determine the stage of liver cancer at the time of diagnosis, or the patient may need more tests. These tests may include imaging tests, such as a CT scan, MRI, angiogram, or ultrasound. Imaging tests can help the doctor find out whether the liver cancer has spread. The doctor also may use a laparoscope to look directly at the liver and nearby organs.

Treatment

Many people with liver cancer want to take an active part in decisions about their medical care. They want to learn all they can about their disease and their treatment choices. However, the shock and stress that people often feel after a diagnosis of cancer can make it hard for them to think of everything they want to ask the doctor. Often it helps to make a list of questions before an appointment. To help remember what the doctor says, patients may want to take notes or ask whether they may use a tape recorder. Some patients also want to have a family member or friend with them when they talk to the doctor -- to take part in the discussion, to take notes, or just to listen.

At this time, liver cancer can be cured only when it is found at an early stage (before it has spread) and only if the patient is healthy enough to have an operation. However, treatments other than surgery may be able to control the disease and help patients live longer and feel better. When a cure or control of the disease is not possible, some patients and their doctors choose palliative therapy. Palliative therapy aims to improve the quality of a person's life by controlling pain and other problems caused by the disease.

The doctor may refer patients to doctors who specialize in treating cancer, or patients may ask for a referral. Specialists who treat liver cancer include surgeons, transplant surgeons, gastroenterologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists.

Getting a Second Opinion

Before starting treatment, a patient may want to get a second opinion about the diagnosis, the stage of cancer, and the treatment plan. Some insurance companies require a second opinion; others may cover a second opinion if the patient requests it.

There are a number of ways to find a doctor for a second opinion:

The doctor may refer patients to one or more specialists. At cancer centers, several specialists often work together as a team. The Cancer Information Service (1-800-4-CANCER) can tell callers about treatment facilities, including cancer centers and other programs supported by the National Cancer Institute, and can send printed information about finding a doctor. A local medical society, a nearby hospital, or a medical school can usually provide the names of specialists. The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) has a list of doctors who have met certain education and training requirements and have passed specialty examinations. The Official ABMS Directory of Board Certified Medical Specialists lists doctors' names along with their specialty and their educational background. The directory is available in most public libraries. Also, ABMS offers this information on the Internet at http://www.abms.org. (Click on "Who's Certified.")

Treatment Choices

The doctor can describe treatment choices and discuss the results expected with each treatment option. The doctor and patient can work together to develop a treatment plan that fits the patient's needs.

Cancer of the liver is very hard to control with current treatments. For that reason, many doctors encourage patients with liver cancer to consider taking part in a clinical trial. Clinical trials are research studies testing new treatments. They are an important option for people with all stages of liver cancer. The section called

"The Promise of Cancer Research 3" has more information about clinical trials.

The choice of treatment depends on the condition of the liver; the number, size, and location of tumors; and whether the cancer has spread outside the liver. Other factors to consider include the patient's age, general health, concerns about the treatments and their possible side effects, and personal values.

Usually, the most important factor is the stage of the disease. The stage is based on the size of the tumor, the condition of the liver, and whether the cancer has spread. The following are brief descriptions of the stages of liver cancer and the treatments most often used for each stage. For some patients, other treatments may be appropriate.

Localized resectable cancer

Localized resectable liver cancer is cancer that can be removed during surgery. There is no evidence that the cancer has spread to the nearby lymph nodes or to other parts of the body. Lab tests show that the liver is working well.

Surgery to remove part of the liver is called partial hepatectomy. The extent of the surgery depends on the size, number, and location of the tumors. It also depends on how well the liver is working. The doctor may remove a wedge of tissue that contains the liver tumor, an entire lobe, or an even larger portion of the liver.

In a partial hepatectomy, the surgeon leaves a margin of normal liver tissue. This remaining healthy tissue takes over the functions of the liver.

For a few patients, liver transplantation may be an option. For this procedure, the transplant surgeon removes the patient's entire liver (total hepatectomy) and replaces it with a healthy liver from a donor. A liver transplant is an option only if the disease has not spread outside the liver and only if a suitable donated liver can be found. While the patient waits for a donated liver to become available, the health care team monitors the patient's health and provides other treatments, as necessary.

Localized unresectable cancer

Localized unresectable liver cancer cannot be removed by surgery even though it has not spread to the nearby lymph nodes or to distant parts of the body. Surgery to remove the tumor is not possible because of cirrhosis (or other conditions that cause poor liver function), the location of the tumor within the liver, or other health problems.

Patients with localized unresectable cancer may receive other treatments to control the disease and extend life:

Radiofrequency ablation -- The doctor uses a special probe to kill the cancer cells with heat. The probe contains tiny electrodes that destroy the cancer cells. Sometimes the doctor can insert the probe directly through the skin. Only local anesthesia is needed. In other cases, the doctor may insert the probe through a small incision in the abdomen or may make a wider incision to open the abdomen. These procedures are done in the hospital with general anesthesia.

Other therapies that use heat to destroy liver tumors include laser or microwave therapy.

Percutaneous ethanol injection -- The doctor injects alcohol (ethanol) directly into the liver tumor to kill cancer cells. The doctor uses ultrasound to guide a small needle. The procedure may be performed once or twice a week. Usually local anesthesia is used, but if the patient has many tumors in the liver, general anesthesia may be needed. Cryosurgery -- The doctor makes an incision into the abdomen and inserts a metal probe to freeze and kill cancer cells. The doctor may use ultrasound to help guide the probe. Hepatic arterial infusion -- The doctor inserts a tube (catheter) into the hepatic artery, the major artery that supplies blood to the liver. The doctor then injects an anticancer drug into the catheter. The drug flows into the blood vessels that go to the tumor. Because only a small amount of the drug reaches other parts of the body, the drug mainly affects the cells in the liver.

Hepatic arterial infusion also can be done with a small pump. The doctor implants the pump into the body during surgery. The pump continuously sends the drug to the liver.

Chemoembolization -- The doctor inserts a tiny catheter into an artery in the leg. Using x-rays as a guide, the doctor moves the catheter into the hepatic artery. The doctor injects an anticancer drug into the artery and then uses tiny particles to block the flow of blood through the artery. Without blood flow, the drug stays in the liver longer. Depending on the type of particles used, the blockage may be temporary or permanent. Although the hepatic artery is blocked, healthy liver tissue continues to receive blood from the hepatic portal vein, which carries blood from the stomach and intestine. Chemoembolization requires a hospital stay. Total hepatectomy with liver transplantation -- If localized liver cancer is unresectable because of poor liver function, some patients may be able to have a liver transplant. While the patient waits for a donated liver to become available, the health care team monitors the patient's health and provides other treatments, as necessary.

|

Advanced cancer

Advanced cancer is cancer that is found in both lobes of the liver or that has spread to other parts of the body. Although advanced liver cancer cannot be cured, some patients receive anticancer therapy to try to slow the progress of the disease. Others discuss the possible benefits and side effects and decide they do not want to have anticancer therapy. In either case, patients receive palliative care to reduce their pain and control other symptoms.

Treatment for advanced liver cancer may involve chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both:

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells. The patient may receive one drug or a combination of drugs. The doctor may use chemoembolization or hepatic arterial infusion. Or the doctor may give systemic therapy, meaning that the drugs are injected into a vein and flow through the bloodstream to nearly every part of the body. The doctor may call this intravenous or IV chemotherapy.

Usually chemotherapy is an outpatient treatment given at the hospital, clinic, or at the doctor's office. However, depending on which drugs are given and the patient's general health, the patient may need to stay in the hospital.

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) uses high-energy rays to kill cancer cells. Radiation therapy is local therapy, meaning that it affects cancer cells only in the treated area. A large machine outside the body directs radiation to the tumor area.

Recurrent cancer

Recurrent cancer means the disease has come back after the initial treatment. Even when a tumor in the liver seems to have been completely removed or destroyed, the disease sometimes returns because undetected cancer cells remained somewhere in the body after treatment. Most recurrences occur within the first 2 years of treatment. The patient may have surgery or a combination of treatments for recurrent liver cancer.

These are some questions a person may want to ask the doctor before treatment begins:

Is there any evidence the cancer has spread? What is the stage of the disease? Do I need any more tests to determine whether I can have surgery? What are my treatment choices? Which do you recommend for me? Why? What are the expected benefits of each kind of treatment? What are the risks and possible side effects of each treatment? Will I need to stay in the hospital? How will you treat my pain? What is the treatment likely to cost? Is this treatment covered by my insurance plan? How will treatment affect my normal activities? Would a clinical trial (research study) be appropriate for me?

|

People do not need to ask all of their questions or understand all of the answers at once. They will have other chances to ask the health care team to explain things that are not clear and to ask for more information.

Side Effects of Treatment

Because cancer treatment may damage healthy cells and tissues, unwanted side effects often occur. Side effects depend on many factors, including the type and extent of the treatment. Side effects may not be the same for each person, and they may even change from one treatment session to the next. The health care team will explain the possible side effects of treatment and how they will help the patient manage them.

The NCI provides helpful booklets about cancer treatments and coping with side effects, such as Chemotherapy and You 4, Radiation Therapy and You 5, and Eating Hints for Cancer Patients 6. See the

"National Cancer Institute Information Resources 7" and

"National Cancer Institute Booklets 8" sections for other sources of information about side effects.

It takes time to heal after surgery, and the time needed to recover is different for each person. Patients are often uncomfortable during the first few days. However, medicine can usually control their pain. Patients should feel free to discuss pain relief with the doctor or nurse. It is common to feel tired or weak for a while. Also, patients may have diarrhea and a feeling of fullness in the abdomen. The health care team watches the patient for signs of bleeding, infection, liver failure, or other problems requiring immediate treatment.

After a liver transplant, the patient may need to stay in the hospital for several weeks. During that time, the health care team checks for signs of how well the patient's body is accepting the new liver. The patient takes drugs to prevent the body from rejecting the new liver. These drugs may cause puffiness in the face, high blood pressure, or an increase in body hair.

Because a smaller incision is needed for cryosurgery than for traditional surgery, recovery after cryosurgery is generally faster and less painful. Also, infection and bleeding are not as likely.

Patients may have fever and pain after percutaneous ethanol injection. The doctor can suggest medicines to relieve these problems.

Chemoembolization and hepatic arterial infusion cause fewer side effects than systemic chemotherapy because the drugs do not flow through the entire body. Chemoembolization sometimes causes nausea, vomiting, fever, and abdominal pain. The doctor can give medications to help lessen these problems. Some patients may feel very tired for several weeks after the treatment.

Side effects from hepatic arterial infusion include infection and problems with the pump device. Sometimes the device may have to be removed.

The side effects of chemotherapy depend mainly on the drugs and the doses the patient receives. As with other types of treatment, side effects are different for each patient.

Systemic chemotherapy affects rapidly dividing cells throughout the body, including blood cells. Blood cells fight infection, help the blood to clot, and carry oxygen to all parts of the body. When anticancer drugs damage blood cells, patients are more likely to get infections, may bruise or bleed easily, and may have less energy. Cells in hair roots and cells that line the digestive tract also divide rapidly. As a result, patients may lose their hair and may have other side effects such as poor appetite, nausea and vomiting, or mouth sores. Usually, these side effects go away gradually during the recovery periods between treatments or after treatment is complete. The health care team can suggest ways to relieve side effects.

The side effects of radiation therapy depend mainly on the treatment dose and the part of the body that is treated. Patients are likely to become very tired during radiation therapy, especially in the later weeks of treatment. Resting is important, but doctors usually advise patients to try to stay as active as they can.

Radiation therapy to the chest and abdomen may cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or urinary discomfort. Radiation therapy also may cause a decrease in the number of healthy white blood cells, cells that help protect the body against infection. Although the side effects of radiation therapy can be distressing, the doctor can usually treat or control them.

Pain Control

Pain is a common problem for people with liver cancer. The tumor can cause pain by pressing against nerves and other organs. Also, therapies for liver cancer may cause discomfort.

The patient's doctor or a specialist in pain control can relieve or reduce pain in several ways:

Pain medicine -- Medicines often can relieve pain. (These medicines may make people drowsy and constipated, but resting and taking laxatives can help.) Radiation -- High-energy rays can help relieve pain by shrinking the tumor. Nerve block -- The doctor may inject alcohol into the area around certain nerves in the abdomen to block the pain.

The health care team may suggest other ways to relieve or reduce pain. For example, massage, acupuncture, or acupressure may be used along with other approaches. Also, the patient may learn to relieve pain through relaxation techniques such as listening to slow music or breathing slowly and comfortably.

More information about pain control can be found in the NCI publications called Pain Control: A Guide for People with Cancer and Their Families 9, Get Relief from Cancer Pain 10, and Understanding Cancer Pain 11. The Cancer Information Service can send these booklets.

Nutrition

People with liver cancer may not feel like eating, especially if they are uncomfortable or tired. Also, the side effects of treatment can make eating difficult. Foods may smell or taste different. Nevertheless, patients should try to eat enough calories and protein to control weight loss, maintain strength, and promote healing. Also, eating well often helps people with cancer feel better and have more energy.

Careful planning and checkups are important. Liver cancer and its treatment may make it hard for patients to digest food and maintain their weight. The doctor will check the patient for weight loss, weakness, and lack of energy.

The doctor, dietitian, or other health care provider can advise patients about ways to have a healthy diet during treatment. Patients and their families may want to read the National Cancer Institute booklet Eating Hints for Cancer Patients 6, which contains many useful suggestions and recipes. The section

"National Cancer Institute Booklets 8" tells how to get this publication.

Continuing Care

Continuing care for patients with liver cancer depends on the stage of their disease and the treatments they have received. Followup is very important after surgery to remove cancer from the liver. This is because the cancer can return in the liver or in another part of the body. People who have had liver cancer surgery may wish to discuss the chance of recurrence with the doctor. Followup care may include blood tests, x-rays, ultrasound tests, CT scans, angiograms, or other tests.

For people who have had a liver transplant, the doctor will test how well the new liver is working. The doctor also will watch the patient closely to make sure the new liver is not being rejected. People who have had a liver transplant may want to discuss with the doctor the type and schedule of followup tests that will be needed.

For patients with advanced disease, the health care team will focus on keeping the patient as comfortable as possible. Medicines and other measures can help with digestion, reduce pain, or relieve other symptoms.

Support for People with Liver Cancer

Having a serious disease such as liver cancer is not easy. Some people find they need help coping with the emotional and practical aspects of their disease. Support groups can help. In these groups, patients or their family members get together to share what they have learned about coping with the disease and the effects of treatment. Patients may want to talk with a member of their health care team about finding a support group. Groups may offer support in person, over the telephone, or on the Internet.

Patients may worry about caring for their families, holding on to their jobs, or keeping up with daily activities. Concerns about treatments and managing side effects, hospital stays, and medical bills are also common. Doctors, nurses, and other members of the health care team will answer questions about treatment, working, or other activities. Meeting with a social worker, counselor, or member of the clergy can be helpful to those who want to talk about their feelings or discuss their concerns. Often, a social worker can suggest resources for emotional support, financial aid, transportation, or home care.

Printed materials on coping are available from the Cancer Information Service (1-800-4-CANCER) and through other sources listed in the

"National Cancer Institute Information Resources 7" section. The Cancer Information Service can also provide information to help patients and their families locate the programs and services they need.

The Promise of Cancer Research

Laboratory scientists are studying the liver to learn more about what may cause liver cancer and how liver cancer cells work. They are looking for new therapies to kill cancer cells.

Doctors in hospitals and clinics are conducting many types of clinical trials. These are research studies in which people take part voluntarily. In these trials, researchers are studying ways to treat liver cancer that have shown promise in laboratory studies. Research has led to advances in treatment methods, but controlling liver cancer remains a challenge. Scientists continue to search for more effective ways to treat this disease.

Patients who join clinical trials have the first chance to benefit from new treatments. They also make an important contribution to medical science. Although clinical trials may pose some risks, researchers take very careful steps to protect people.

Currently, clinical trials involve chemotherapy, chemoembolization, and radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of liver cancer. Another approach under study is biological therapy, which uses the body's natural ability (immune system) to fight cancer. Biological therapy is being studied in combination with chemotherapy.

Patients who are interested in joining a clinical study should talk with their doctor. They may want to read the NCI booklet Taking Part in Cancer Treatment Research Studies 12. It explains how clinical trials are carried out and explains their possible benefits and risks. NCI's Web site at http://www.cancer.gov provides general information about clinical trials. It also offers detailed information about specific ongoing studies of liver cancer by linking to PDQ®, 13 NCI's cancer information database. The Cancer Information Service at 1-800-4-CANCER can answer questions about cancer clinical trials and can provide information from the PDQ database.

National Cancer Institute Booklets

National Cancer Institute (NCI) publications can be ordered by writing to the address below, and some can be viewed and downloaded from http://www.cancer.gov/publications on the Internet.

Publications Ordering Service

National Cancer Institute

Suite 3036A

6116 Executive Boulevard, MSC 8322

Bethesda, MD 20892-8322

In addition, people in the United States and its territories may order these and other NCI booklets by calling the Cancer Information Service at 1-800-4-CANCER. They may also order many NCI publications on-line at http://www.cancer.gov/publications.

See the complete index of What You Need To Know About™ Cancer 14 publications.

Booklets About Cancer Treatment

Booklets About Living With Cancer

Booklets About Cancer Research

National Cancer Institute Information Resources

You may want more information for yourself, your family, and your doctor. The following National Cancer Institute (NCI) services are available to help you.

Cancer Information Service 1 (CIS)

Provides accurate, up-to-date information on cancer to patients and their families, health professionals, and the general public. Information specialists translate the latest scientific information into understandable language and respond in English, Spanish, or on TTY equipment.

Toll-free: 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237)

TTY (for deaf and hard of hearing callers): 1-800-332-8615

http://www.cancer.gov

NCI's Web site contains comprehensive information about cancer causes and prevention, screening and diagnosis, treatment and survivorship; clinical trials; statistics; funding, training, and employment opportunities; and the Institute and its programs.

|