Feature

Big-Bang Work Brings Big Prize

05.07.07

| Who are NASA's Space Science Explorers? Who are NASA's Space Science Explorers? The scientist studying black holes in distant galaxies. And the engineer working on robotic machines bound for space. But also the teacher explaining the mysteries of the cosmos. And the student wondering if there is life beyond Earth. All of these people are Space Science Explorers. They are all linked by their quest to explore our solar system and universe. This monthly series will introduce you to NASA Space Science Explorers, young and old, with many backgrounds and interests. Nominate a Space Science Explorer! Tell us about the Space Science Explorers you know. We're looking for students, teachers, scientists and others who have a connection to NASA, whether they work for the agency or are involved in a NASA-supported mission or program. Send your nominations to Dan Stillman: dan_stillman@strategies.org. |

|

Though widely accepted, the big-bang theory is hard to prove with 100 percent certainty. NASA's John Mather likes a challenge, so he thought he'd give it a shot. In 1974, he proposed a satellite mission to gather proof for the hard-to-prove theory. Now, more than 30 years later, he is being rewarded for his work.

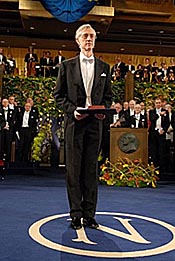

Image to left: John Mather receives the Nobel Prize for Physics. Copyright: The Nobel Foundation 2006. Credit: Hans Mehlin

Mather and fellow scientist George Smoot were recently given one of the greatest honors in science. They won the 2006 Nobel Prize for Physics. Mather is the first NASA scientist to win a Nobel Prize. Smoot works at the University of California, Berkeley.

Thirty-two years may seem like a long time to wait for an award, but during that time Mather has learned the importance of hard work and patience.

Mather and his team started building the satellite, named COBE, in 1982. COBE is short for the Cosmic Background Explorer. Four years later, Mather's team suffered a setback. COBE had been designed for launch on the space shuttle. But in 1986, the shuttle fleet was grounded after the Challenger accident.

Engineers on his team found a way to reduce the satellite's weight, and they moved some of its parts. The changes made it possible to launch COBE on a Delta 2 rocket. COBE finally made it to space in 1989. The mission turned out to be a huge success. It led to the strongest proof yet of the big-bang theory.

|

Back in 1929, Edwin Hubble discovered that distant galaxies were traveling away from Earth at tremendous speeds. This movement showed that the universe is expanding. Scientists then suggested the big bang as a way to explain why galaxies would be moving away.

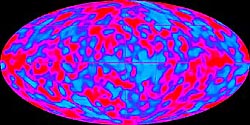

The theory also predicted that the universe is filled with leftover radiation from the original explosion. A little more than 40 years ago, two other scientists accidentally discovered this radiation, which cannot be seen with human eyes. It's called the cosmic microwave background radiation, because it emits waves of energy in the microwave portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. This discovery was the first strong evidence for the big bang, and won those two scientists a Nobel Prize in 1978.

Mather and Smoot and the COBE science team wanted more solid proof. Working with engineers at Goddard Space Flight Center, the team conceived and built the COBE mission, which would measure the cosmic microwave background radiation in two different ways. One was to measure the intensity of the radiation. The other was to see if the intensity was equal in all directions, which is what the big-bang theory predicts.

|

Related Resources + Starchild: Cosmology + Previous Space Science Explorers articles |

"Being a scientist is one of the most exciting things that I could imagine doing," he said. "And if you love solving puzzles, if you love finding out things that are unknown, it's just the thing [to do]."

Adapted for grades 5-8 by Dan Stillman, Institute for Global Environmental Strategies