|

|

Health Topics

Nutrition

Nutrition and the Health of Young People

Benefits of Healthy Eating

-

Healthy eating contributes to overall healthy

growth and development, including healthy bones, skin, and energy

levels; and a lowered risk of dental caries, eating disorders,

constipation, malnutrition, and iron deficiency anemia.1

Diet and Disease

- Early indicators of atherosclerosis, the most common cause of heart disease,

begin as early as childhood and adolescence. Atherosclerosis is related to

high blood cholesterol levels, which are associated with poor dietary

habits.2

- Osteoporosis, a disease where bones become fragile and can break easily, is

associated with inadequate intake of calcium.3

- Type 2 diabetes, formerly known as adult onset diabetes, has become

increasingly prevalent among children and adolescents as rates of overweight

and obesity rise.4 A CDC study estimated that one in three American children

born in 2000 will develop diabetes in their lifetime.5

- Overweight and obesity, influenced by poor diet and inactivity, are

significantly associated with an increased risk of diabetes, high blood

pressure, high cholesterol, asthma, joint problems,

and poor health status.6

Obesity Among Youth

-

The prevalence of overweight among children aged 6-11 years has more than

doubled in the past 20 years and among adolescents aged 12-19 has more than

tripled.7,8

-

Overweight children and adolescents

are more likely to become overweight or obese adults;9 one

study showed that children who became obese by age 8 were more severely

obese as adults.10

Eating Behaviors of Young People

- Less than 40% of children and adolescents in the United States

meet the U.S. dietary guidelines

for saturated fat.11

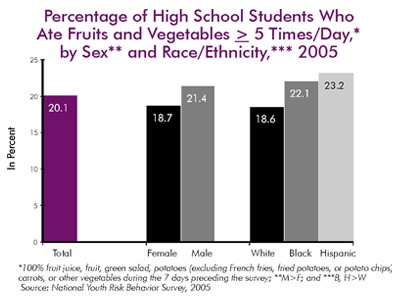

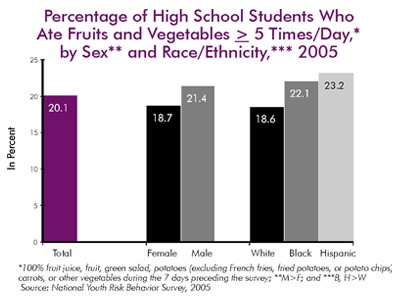

- Eighty percent of high school students do not eat fruits and

vegetables 5 or more times per day.12

- Only 39% of children ages 2-17 meet the USDA抯 dietary

recommendation for fiber (found

primarily in dried beans and peas, fruits, vegetables, and whole

grains).13

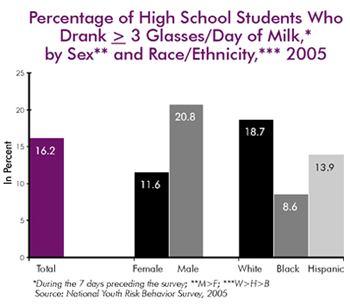

- Eighty-five percent of adolescent females do not consume enough

calcium.3 During the last 25 years, consumption of milk, the

largest source of calcium, has decreased 36% among adolescent

females.14 Additionally, from 1978 to 1998, average daily soft

drink consumption almost doubled among adolescent females,

increasing from 6 ounces to 11 ounces, and almost tripled among

adolescent males, from 7 ounces to 19 ounces.11, 15

- A large number of high school students use unhealthy methods to

lose or maintain weight. A nationwide survey found that during

the 30 days preceding the survey, 12.3% of students went without

eating for 24 hours or more; 4.5% had vomited or taken laxatives

in order to lose weight; and

6.3% had taken

diet pills, powders, or liquids without a doctor's advice.12

Diet and Academic Performance

-

Research suggests that not having breakfast can

affect children's intellectual performance.16

-

The percentage of young people who eat breakfast

decreases with age; while 92% of children ages 6� eat breakfast, only 77%

of adolescents ages 12� eat breakfast.11

-

Hunger and food insufficiency in children are

associated with poor behavioral and academic functioning.17,18

References

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of

Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 6th Edition,

2005. Washington, DC, U.S. Government Printing Office.

-

Kavey RW, Daniels SR, Lauer RM, Atkins DL, Hayman LL, Taubert K.

American Heart Association guidelines for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease beginning in childhood.

Journal of Pediatrics 2003;142(4):368-372.

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Bone Health and

Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Humans Services, Office of the Surgeon General,

2004.

-

Rosenbloom AL, Joe JR, Young RS, Winter WE. Emerging epidemic of type

2 diabetes in youth. Diabetes Care 1999;22(2):345-354.

-

Venkat Narayan KM, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Sorensen SW, Williamson DF.

Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association 2003;290(14):1884-1890.

-

Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, et al. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related

health risk factors, 2001. Journal of the American Medical Association

2003;289(1):76-79.

-

Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in

overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999-2000. Journal of the American Medical Association 2002;288:1728-32.

-

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM.

Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States,1999-2004. Journal of the American Medical Association

2006;295:1549-1555.

-

Ferraro KF, Thorpe RJ Jr, Wilkinson JA. The life course of severe

obesity: Does childhood overweight matter? Journal of Gerontology 2003;58B(2):S110-S119.

-

Freedman DS, Khan LK, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS.

Relationship of childhood obesity to coronary heart disease risk factors in adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study.

Pediatrics

2001;108(3):712-18.

-

U.S. Department of Agriculture. Continuing Survey of Food

Intakes by Individuals 1994-96, 1998.

-

CDC.

Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance桿nited States, 2005

[pdf 300K]. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report 2006;55(SS-5):1�8.

-

Lin BH, Guthrie J, Frazao E. American children抯 diets not making

the grade. Food Review 2001;24(2):8-17.

-

Cavadini C, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. US adolescent food intake

trends from 1965 to 1996. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2000;83(1):18-24.

-

U.S. Department of Agriculture. Continuing Survey of Food

Intakes by Individuals, 1987-88, Appendix A.

-

Pollitt E, Matthews R. Breakfast and cognition: an integrative

summary. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1998;67(suppl): 804S-813S.

-

Alaimo K, Olson CM, and Frongillo EA. "Food Insufficiency and American

School-Aged Children's Cognitive, Academic and Psychosocial

Developments." Pediatrics 108.1 (2001):44�.

-

Kleinman, R. E., et al. "Hunger in children in the United States:

Potential behavioral and emotional correlates." Pediatrics 101

(1998):1�

Back to Top

October 2007

Documents on this page are available in

Portable Document Format (PDF). Learn more about viewing and printing

these documents with Acrobat

Reader.

|

|