Feature

SPACEHAB Ready for Last Mission

07.16.07

The company provided its first space-rated travel trailer of sorts to NASA in 1993. Later, the design would come in especially handy for missions to the Mir space station and during the construction and outfitting of the International Space Station.

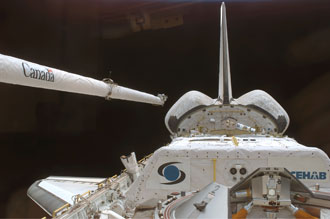

Image right: A SPACEHAB module is loaded into a payload canister to be taken out to the launch pad where it will be loaded into the space shuttle Endeavour. Photo credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann

Image right: A SPACEHAB module is loaded into a payload canister to be taken out to the launch pad where it will be loaded into the space shuttle Endeavour. Photo credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann The single module bolted into Endeavour's cargo bay will continue that work by carrying some 5,800 pounds of equipment and supplies to the International Space Station, according to Don Moore, director of ground operations at the company's Cape Canaveral, Fla., facility.

"We're all sad that this is the last module mission," Moore said. "It's kind of hard to see that go away."

Pete Paceley, SPACEHAB Flight Services V.P. said, “but it is a transition flight for us and we’re excited about the demonstration tests for microgravity processing that we’re flying as well.”

NASA could still enlist a pressurized SPACEHAB module for a shuttle supply run in the future, but the flight manifest currently leaves that task to the Italian-built multi-purpose logistics modules.

The MPLMs are built to attach directly to the space station during a shuttle mission, but still come back with the orbiter. A module from SPACEHAB remains in the cargo bay during the entire flight.

For now, SPACEHAB is keeping its two modules certified for flight until the shuttles retire in 2010.

Since flying its first pressurized module in 1993 aboard STS-57, the company has claimed the mantle of a successful aerospace corporation by catering to researchers and others willing to pay to get their experiments into space and back aboard an orbiter.

Image left: Space Shuttle Discovery recently carried a SPACEHAB module as part of its mission to resupply the International Space Station. The modules can hold spare parts, equipment and supplies, or can act as laboratories of their own, depending on the mission. Photo credit: NASA

Image left: Space Shuttle Discovery recently carried a SPACEHAB module as part of its mission to resupply the International Space Station. The modules can hold spare parts, equipment and supplies, or can act as laboratories of their own, depending on the mission. Photo credit: NASAMissions often left enough room for other paying research customers.

"Anybody that flew liked the ease that they could come in and work in our facilities," Moore said.

“Our future depends on our ability to leverage our unique capabilities, engineering expertise, and application of commercial processes for spaceflight processing,” Paceley said.

Among the hundreds of past experiments carried out aboard the modules include aerogel, the super-lightweight substance that became the centerpiece of the Stardust mission to gather particles from interstellar space.

He emphasized that the company could quickly fly an experiment again, too, something that NASA could not always do.

"We'd always find room for it," Moore said.

That approach is also fueling plans for corporate life after the shuttle retires. In addition to the utilization of the ISS for microgravity processing, the company is also working on a spacecraft that could ride atop expendable rockets and carry self-contained experiments or manufacturing elements into orbit.

But Moore's focus is on Endeavour's upcoming flight, and there is plenty to focus on.

Just packing the module takes considerable planning, especially considering that some of the bags have to be loaded while the module is on its back inside Endeavour at the launch pad.

Image right: Crew members for mission STS-118 familiarize themselves with the SPACEHAB module they will unload while at the International Space Station. The cargo module will be packed with equipment and supplies. Photo credit: NASA/Kim Shiflett

Image right: Crew members for mission STS-118 familiarize themselves with the SPACEHAB module they will unload while at the International Space Station. The cargo module will be packed with equipment and supplies. Photo credit: NASA/Kim ShiflettMoore said the loaders devise a complex choreography to get the 5,800 pounds of gear on racks and stacked in bags exactly where the astronauts expect to find it.

"You get down to people's weight, who's going to go down first, who's going to go down second," he said.

The company uses mock-ups of the module to fine-tune the routine. Astronauts typically get some time in the actual module and the trainers to find out what they will see once they reach space.

In the case of STS-118, the crew can expect a tight fit in the module because of all the gear strapped to the walls. The good news is that what seems like a tight fit on Earth opens up significantly in space, where the lack of gravity lets astronauts float up to the module's window. Crew members can also tuck themselves into crevices and sleep inside the module.

As with all the missions that carry a SPACEHAB element, Moore will sit in the Launch Control Center at Kennedy Space Center during launch before heading to Mission Control at Johnson Space Center to oversee the module during the flight.

"Every launch is special," he said. "I think we're just going to be on the edge of our seats."

NASA's John F. Kennedy Space Center