|

To date, four Nobel Prizes (all in Physiology or Medicine)

have been awarded for work associated with malaria.

|

|

Alphonse Laveran (L) and Ronald Ross (R), malaria

pioneers whose discoveries were recognized by Nobel Prizes.

(Courtesy:

Service de Santé des Armées [Health Services of the Armed Forces],

France; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine) |

|

Two Nobel Prizes recognized key discoveries on the nature of malaria and its

transmission:

- Alphonse Laveran was awarded

the prize in 1907 "in recognition of his work on the role played by protozoa in causing

diseases". On November 6, 1880, Laveran, a French army surgeon stationed in Constantine,

Algeria, was the first to notice parasites in the blood of a patient suffering from malaria.

|

|

|

Alphonse Laveran (L) and Ronald Ross

(R)

(Courtesy: Service de Santé des Armées [Health

Services of the Armed Forces], France; London School of Hygiene and Tropical

Medicine) |

|

Ronald Ross was awarded the prize in

1902, "for his work on malaria, by which he has shown how it enters the organism and thereby

has laid the foundation for successful research on this disease and methods of combating it". On August 20, 1897, Ronald Ross, a British

officer in the Indian Medical Service, was the first to demonstrate that malaria parasites

could be transmitted from infected patients to mosquitoes. In further work with bird

malaria, Ross showed that mosquitoes could transmit malaria parasites from bird to bird.

Thus, the problem of malaria transmission was solved.

A third Nobel Prize was awarded for work that used malaria to treat another disease:

- Julius Wagner-Jauregg received the

1927 Nobel

Prize "for his discovery of the therapeutic value of malaria inoculation in the treatment

of dementia paralytica". A professor of psychiatry and neurology in Vienna (Austria),

Wagner-Jauregg developed methods for treating general paresis ("dementia paralytica"; the

neurologic, advanced stage of syphilis) by

inducing fever through deliberate infection of patients with malaria parasites. While this

method was not always effective or devoid of risks, it was used in the 1920s and 1930s. In

the 1940s, the advent of penicillin and more modern methods of treatment made such "malaria

therapy" obsolete.

A fourth Nobel Prize was awarded for a discovery that deeply influenced malaria control:

|

|

|

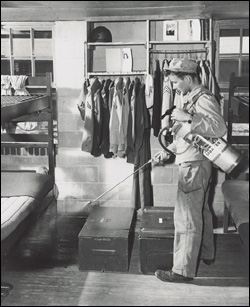

Indoor DDT spraying in the 1940s in a military

facility in the Southeastern United States, shortly after this insecticide was

introduced. |

|

Paul Hermann Müller received the

1948 Nobel

Prize "for his discovery of the high efficiency of DDT as a contact poison against

several arthropods". This Swiss chemist discovered the insecticidal properties of DDT

(dichloro-diphenyl-trichlorethane) in 1939 while working at the firm J. R. Geigy in Basel,

Switzerland. Products containing DDT were marketed in 1942. This synthetic insecticide

proved invaluable in fighting epidemic

typhus

(a disease transmitted by lice) during World War II. DDT's greatest public health use was

probably in controlling malaria, thanks to its combined advantages of insecticidal

properties, lack of acute toxicity to humans, and long duration of action. In malaria-endemic

areas, spraying DDT twice a year on the inside walls of houses could prevent mosquitoes

from transmitting malaria. This strategy,

"indoor residual insecticide spraying",

contributed to the eradication of malaria from many countries (including the

United States) during the 1950s - 1970s. In

addition to its public health role, DDT also found substantial use as an agricultural

insecticide. However, the usefulness of DDT has now been severely curtailed. Insects

resistant to DDT have evolved, and DDT resistance is one of the factors blamed for the failure

in the 1970s of the malaria eradication campaign (although

DDT is still effective in controlling malaria in many countries today). Concerns have been

raised that accumulation and persistence of DDT, predominantly from agricultural use, may

result in negative environmental impact. Because of these concerns, the agricultural use of

DDT is banned in all countries, although its use for malaria control is still permitted in

some countries until suitable replacement insecticides are found.

Page last modified : January 26, 2004

Content source: Division of Parasitic Diseases

National Center for Zoonotic, Vector-Borne, and Enteric Diseases (ZVED)

|

|

|