Introduction

The Skin

Understanding Skin Cancer

Risk Factors

Prevention

Symptoms

Diagnosis

Staging

Treatment

Follow-up Care

Sources of Support

The Promise of Cancer Research

How To Do a Skin Self-Exam

National Cancer Institute Information Resources

National Cancer Institute Publications

Introduction

This National Cancer Institute (NCI) booklet has important information about

skin

cancer.*

Skin cancer is the most common type of cancer in this country.

About one million Americans develop skin cancer each year.

You will read about causes and ways to prevent skin cancer. You will find

information about symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. You will also learn how

to do a skin self-exam.

Scientists are studying skin cancer to find out more about how it develops. And

they are looking for better ways to prevent and treat it.

|

There are many types of skin cancer. This booklet is about the two most common

types, basal cell cancer and squamous cell cancer. These are sometimes called

nonmelanoma skin cancer. A much less common type of skin cancer, melanoma, is

not discussed in this booklet. To learn about this disease, see the NCI booklet

What You Need To Know About Melanoma 1.

|

NCI provides information about cancer, including the publications mentioned in

this booklet. You can order these materials by telephone or on the Internet.

You can also read them on the Internet and print your own copy.

-

Telephone (1-800-4-CANCER): Information Specialists at NCI's Cancer

Information Service can answer your questions about cancer. They also can send

NCI booklets, fact sheets, and other materials.

-

Internet (http://www.cancer.gov): You can use NCI's Web

site to find a wide range of up-to-date information. For example, you can find

many NCI booklets and fact sheets at http://www.cancer.gov/publications. People in the United States and

its territories may use this Web site to order printed copies. This Web site

also explains how people outside the United States can mail or fax their

requests for NCI booklets.

You can ask questions online and get help right away from Information

Specialists through

LiveHelp 2 at http://www.cancer.gov/cis.

*Words that may be new to readers appear in italics. The "Dictionary 3"

section explains these terms. Some words in the "Dictionary" have a

"sounds-like" spelling to show how to pronounce them.

The Skin

The skin is the body's largest

organ.

It protects against heat, light, injury,

and

infection.

It helps control body temperature. It stores water and fat. The

skin also makes vitamin D.

The skin has two main layers:

-

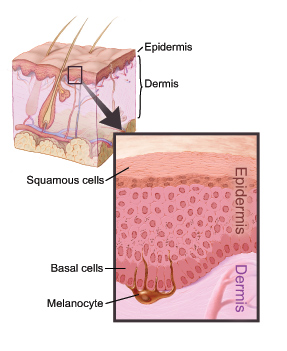

Epidermis:

The epidermis is the top layer of the skin. It is mostly made

of flat

cells.

These are

squamous cells.

Under the squamous cells in the

deepest part of the epidermis are round cells called

basal cells.

Cells called

melanocytes

make the pigment (color) found in skin and are located in the lower

part of the epidermis.

-

Dermis:

The dermis is under the epidermis. It contains blood vessels,

lymph

vessels, and

glands.

Some of these glands make sweat, which helps cool

the body. Other glands make

sebum.

Sebum is an oily substance that helps keep

the skin from drying out. Sweat and sebum reach the surface of the skin through

tiny openings called pores.

|

| This picture shows the layers of the skin. |

Understanding Skin Cancer

Skin cancer begins in cells, the building blocks that make up the skin.

Normally, skin cells grow and divide to form new cells. Every day skin cells

grow old and die, and new cells take their place.

Sometimes, this orderly process goes wrong. New cells form when the skin does

not need them, and old cells do not die when they should. These extra cells can

form a mass of

tissue

called a growth or

tumor.

Growths or tumors can be

benign

or

malignant:

-

Benign growths are not cancer:

-

Benign growths are rarely life-threatening.

-

Generally, benign growths can be removed. They usually do not grow back.

-

Cells from benign growths do not invade the tissues around them.

-

Cells from benign growths do not spread to other parts of the body.

-

Malignant growths are cancer:

-

Malignant growths are generally more serious than benign growths. They may be

life-threatening. However, the two most common types of skin cancer cause only

about one out of every thousand deaths from cancer.

-

Malignant growths often can be removed. But sometimes they grow back.

-

Cells from malignant growths can invade and damage nearby tissues and organs.

-

Cells from some malignant growths can spread to other parts of the body. The

spread of cancer is called

metastasis.

Skin cancers are named for the type of cells that become cancerous.

The two most common types of skin cancer are

basal cell cancer

and

squamous cell cancer.

These cancers usually form on the head, face, neck, hands, and

arms. These areas are exposed to the sun. But skin cancer can occur anywhere.

-

Basal cell skin cancer grows slowly. It usually occurs on areas of the

skin that have been in the sun. It is most common on the face. Basal cell

cancer rarely spreads to other parts of the body.

-

Squamous cell skin cancer also occurs on parts of the skin that have

been in the sun. But it also may be in places that are not in the sun. Squamous

cell cancer sometimes spreads to

lymph nodes

and organs inside the body.

If skin cancer spreads from its original place to another part of the body, the

new growth has the same kind of abnormal cells and the same name as the

primary growth.

It is still called skin cancer.

Risk Factors

Doctors cannot explain why one person develops skin cancer and another does

not. However, we do know that skin cancer is not contagious. You cannot "catch"

it from another person.

Research has shown that people with certain

risk factors

are more likely than

others to develop skin cancer. A risk factor is something that may increase the

chance of developing a disease.

Studies have found the following risk factors for skin cancer:

-

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation: UV radiation comes from the sun, sunlamps,

tanning beds, or tanning booths. A person's risk of skin cancer is related to

lifetime exposure to UV radiation. Most skin cancer appears after age 50, but

the sun damages the skin from an early age.

UV radiation affects everyone. But people who have fair skin that freckles or

burns easily are at greater risk. These people often also have red or blond

hair and light-colored eyes. But even people who tan can get skin cancer.

People who live in areas that get high levels of UV radiation have a higher

risk of skin cancer. In the United States, areas in the south (such as Texas

and Florida) get more UV radiation than areas in the north (such as Minnesota).

Also, people who live in the mountains get high levels of UV radiation.

UV radiation is present even in cold weather or on a cloudy day.

-

Scars or burns on the skin

-

Infection with certain

human papillomaviruses

-

Exposure to arsenic at work

-

Chronic

skin

inflammation

or skin

ulcers

-

Diseases that make the skin sensitive to the sun, such as

xeroderma pigmentosum,

albinism,

and

basal cell nevus syndrome

-

Radiation therapy

-

Medical conditions or drugs that suppress the

immune system

-

Personal history of one or more skin cancers

-

Family history of skin cancer

-

Actinic keratosis:

Actinic keratosis is a type of flat, scaly growth on

the skin. It is most often found on areas exposed to the sun, especially the

face and the backs of the hands. The growths may appear as rough red or brown

patches on the skin. They may also appear as cracking or peeling of the lower

lip that does not heal.

Without treatment, a small number of these scaly growths may turn into squamous

cell cancer.

-

Bowen's disease: Bowen's disease is a type of scaly or thickened patch

on the skin. It may turn into squamous cell skin cancer.

If you think you may be at risk for skin cancer, you should discuss this

concern with your doctor. Your doctor may be able to suggest ways to reduce

your risk and can plan a schedule for checkups.

|

Prevention

The best way to prevent skin cancer is to protect yourself from the sun. Also,

protect children from an early age. Doctors suggest that people of all ages

limit their time in the sun and avoid other sources of UV radiation:

-

It is best to stay out of the midday sun (from mid-morning to late afternoon)

whenever you can. You also should protect yourself from UV radiation reflected

by sand, water, snow, and ice. UV radiation can go through light clothing,

windshields, windows, and clouds.

-

Wear long sleeves and long pants of tightly woven fabrics, a hat with a wide

brim, and sunglasses that absorb UV.

-

Use

sunscreen

lotions. Sunscreen may help prevent skin cancer, especially

broad-spectrum sunscreen (to filter

UVB

and

UVA

rays) with a

sun protection factor (SPF) of at least 15. But you still need to avoid the sun and wear

clothing to protect your skin.

-

Stay away from sunlamps and tanning booths.

Symptoms

Most basal cell and squamous cell skin cancers can be cured if found and treated early.

A change on the skin is the most common sign of skin cancer. This may be a new growth, a sore that doesn't heal, or a change in an old growth. Not all skin cancers look the same. Skin changes to watch for:

- Small, smooth, shiny, pale, or waxy lump

- Firm, red lump

- Sore or lump that bleeds or develops a crust or a scab

- Flat red spot that is rough, dry, or scaly and may become itchy or tender

- Red or brown patch that is rough and scaly

Sometimes skin cancer is painful, but usually it is not.

Checking your skin for new growths or other changes is a good idea. A guide for checking your skin is below 4. Keep in mind that changes are not a sure sign of skin cancer. Still, you should report any changes to your health care provider right away. You may need to see a

dermatologist, a doctor who has special training in the diagnosis and treatment of skin problems.

Diagnosis

If you have a change on the skin, the doctor must find out whether it is due to

cancer or to some other cause. Your doctor removes all or part of the area that

does not look normal. The sample goes to a lab. A

pathologist

checks the sample

under a microscope. This is a

biopsy.

A biopsy is the only sure way to diagnose

skin cancer.

You may have the biopsy in a doctor's office or as an

outpatient in a clinic or hospital. Where it is done depends on the size and

place of the abnormal area on your skin. You probably will have

local anesthesia.

There are four common types of skin biopsies:

-

Punch biopsy:

The doctor uses a sharp, hollow tool to remove a circle of

tissue from the abnormal area.

-

Incisional biopsy:

The doctor uses a

scalpel

to remove part of the

growth.

-

Excisional biopsy:

The doctor uses a scalpel to remove the entire growth

and some tissue around it.

-

Shave biopsy:

The doctor uses a thin, sharp blade to shave off the

abnormal growth.

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before having a biopsy:

-

Which type of biopsy do you recommend for me?

-

How will the biopsy be done?

-

Will I have to go to the hospital?

-

How long will it take? Will I be awake? Will it hurt?

-

Are there any risks? What are the chances of infection or bleeding after the

biopsy?

-

What will my scar look like?

-

How soon will I know the results? Who will explain them to me?

|

Staging

If the biopsy shows that you have cancer, your doctor needs to know the extent

(stage)

of the disease. In very few cases, the doctor may check your lymph

nodes to stage the cancer.

The stage is based on:

-

The size of the growth

-

How deeply it has grown beneath the top layer of skin

-

Whether it has spread to nearby lymph nodes or to other parts of the body

These are the stages of skin cancer:

-

Stage 0: The cancer involves only the top layer of skin. It is

carcinoma in situ.

-

Stage I: The growth is 2 centimeters wide (three-quarters of an inch) or

smaller.

-

Stage II: The growth is larger than 2 centimeters wide (three-quarters

of an inch).

-

Stage III: The cancer has spread below the skin to

cartilage,

muscle,

bone, or to nearby lymph nodes. It has not spread to other places in the body.

-

Stage IV: The cancer has spread to other places in the body.

Treatment

Sometimes all of the cancer is removed during the biopsy. In such cases, no

more treatment is needed. If you do need more treatment, your doctor will

describe your options.

Treatment for skin cancer depends on the type and stage of the disease, the

size and place of the growth, and your general health and medical history. In

most cases, the aim of treatment is to remove or destroy the cancer completely.

It often helps to make a list of questions before an appointment. To help

remember what the doctor says, you may take notes or ask whether you may use a

tape recorder. You may also want to have a family member or friend with you

when you talk to the doctor -- to take part in the discussion, to take notes, or

just to listen.

Your doctor may refer you to a specialist, or you may ask for a referral.

Specialists who treat skin cancer include

dermatologists,

surgeons, and

radiation oncologists.

Before you have treatment, you might want a second opinion about the diagnosis

and treatment plan. Many insurance companies cover a second opinion if you or

your doctor requests it. It may take some time and effort to gather medical

records and arrange to see another doctor. Usually it is not a problem to take

several weeks to get a second opinion. In most cases, the delay will not make

treatment less effective. To make sure, you should discuss this delay with your

doctor. Sometimes people with skin cancer need treatment right away.

There are a number of ways to find a doctor for a second opinion:

-

Your doctor may refer you to one or more specialists. At cancer centers,

several specialists often work together as a team.

-

NCI's Cancer Information Service, at 1-800-4-CANCER, can tell you about nearby

treatment centers. Information Specialists also can provide online assistance

through

LiveHelp 2 at http://www.cancer.gov/cis.

-

A local or state medical society, a nearby hospital, or a medical school can

usually provide the names of specialists.

-

The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) has a list of doctors who have

had training and passed exams in their specialty. You can find this list in the

Official ABMS Directory of Board Certified Medical Specialists. This Directory

is in most public libraries. Also, ABMS offers this information at

http://www.abms.org 5. (Click on "Who's Certified.")

-

NCI provides a helpful fact sheet called "How To Find a Doctor or Treatment

Facility If You Have Cancer 6."

|

You may want to ask the doctor these questions before treatment begins:

-

What is the stage of the disease?

-

What are my treatment choices? Which do you recommend for me? Why?

-

What are the expected benefits of each kind of treatment?

-

What are the risks and possible

side effects

of each treatment? What can we do

to control my side effects?

-

Will the treatment affect my appearance? If so, can a

reconstructive surgeon

or

plastic surgeon

help?

-

Will treatment affect my normal activities? If so, for how long?

-

What is the treatment likely to cost? Does my insurance cover this treatment?

-

How often should I have checkups?

-

Would a

clinical trial

(research study) be appropriate for me?

|

Your doctor can describe your treatment choices and what to expect. You and

your doctor can work together to develop a treatment plan that meets your

needs.

Surgery

is the usual treatment for people with skin cancer. In some cases, the

doctor may suggest

topical chemotherapy,

photodynamic therapy,

or

radiation therapy.

Because skin cancer treatment may damage healthy cells and tissues, unwanted

side effects sometimes occur. Side effects depend mainly on the type and extent

of the treatment. Side effects may not be the same for each person.

Before treatment starts, your doctor will tell you about possible side effects

and suggest ways to help you manage them.

Many skin cancers can be removed quickly and easily. Even so, you may need

supportive care

to control pain and other symptoms, to relieve the side effects

of treatment, and to ease emotional concerns. Information about such care is

available on NCI's Web site at http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/coping,

and from Information Specialists at 1-800-4-CANCER or

LiveHelp 2.

You may want to talk to your doctor about taking part in a clinical trial, a

research study of new ways to treat cancer or prevent it from coming back. The

section on "The Promise of Cancer

Research 4" has more information about clinical trials.

Surgery to treat skin cancer may be done in one of several ways. The method

your doctor uses depends on the size and place of the growth and other factors.

Your doctor can further describe these types of surgery:

-

Excisional skin surgery

is a common treatment to remove skin cancer.

After numbing the area, the surgeon removes the growth with a scalpel. The

surgeon also removes a border of skin around the growth. This skin is the

margin.

The margin is examined under a microscope to be certain that all the

cancer cells have been removed. The size of the margin depends on the size of

the growth.

-

Mohs surgery

(also called Mohs micrographic surgery) is often used for

skin cancer. The area of the growth is numbed. A specially trained surgeon

shaves away thin layers of the growth. Each layer is immediately examined under

a microscope. The surgeon continues to shave away tissue until no cancer cells

can be seen under the microscope. In this way, the surgeon can remove all the

cancer and only a small bit of healthy tissue.

-

Electrodesiccation

and

curettage

is often used to remove small basal

cell skin cancers. The doctor numbs the area to be treated. The cancer is

removed with a sharp tool shaped like a spoon. This tool is a

curette.

An

electric current is sent into the treated area to control bleeding and kill any

cancer cells that may be left. Electrodesiccation and curettage is usually a

fast and simple procedure.

-

Cryosurgery

is often used for people who are not able to have other

types of surgery. It uses extreme cold to treat early stage or very thin skin

cancer. Liquid nitrogen creates the cold. The doctor applies liquid nitrogen

directly to the skin growth. This treatment may cause swelling. It also may

damage nerves, which can cause a loss of feeling in the damaged area. The NCI

fact sheet "Cryosurgery in Cancer Treatment: Questions and Answers 7" has more

information.

-

Laser surgery

uses a narrow beam of light to remove or destroy cancer

cells. It is most often used for growths that are on the outer layer of skin

only. The NCI fact sheet "Lasers in Cancer Treatment: Questions and Answers 8"

has more information.

-

Grafts

are sometimes needed to close an opening in the skin left by

surgery. The surgeon first numbs and then removes a patch of healthy skin from

another part of the body, such as the upper thigh. The patch is then used to

cover the area where skin cancer was removed. If you have a skin graft, you may

have to take special care of the area until it heals.

The time it takes to heal after surgery is different for each person. You may

be uncomfortable for the first few days. However, medicine can usually control

the pain. Before surgery, you should discuss the plan for pain relief with your

doctor or nurse. After surgery, your doctor can adjust the plan if you need

more pain relief.

Surgery nearly always leaves some type of scar. The size and color of the scar

depend on the size of the cancer, the type of surgery, and how your skin heals.

For any type of surgery, including skin grafts or

reconstructive surgery,

it is

important to follow your doctor's advice on bathing, shaving, exercise, or

other activities.

|

You may want to ask your doctor these questions about surgery:

-

What kind of surgery will I have?

-

Will I need a skin graft?

-

What will the scar look like? Can anything be done to help reduce the scar?

Will I need

plastic surgery

or reconstructive surgery?

-

How will I feel after the operation?

-

If I have pain, how will it be controlled?

-

Will I have to stay in the hospital?

-

Am I likely to have infection, swelling, blistering, or bleeding, or to get a

scab where the cancer was removed?

|

Chemotherapy uses anticancer drugs to kill skin cancer cells. When a drug is

put directly on the skin, the treatment is topical chemotherapy. It is most

often used when the skin cancer is too large for surgery. It is also used when

the doctor keeps finding new cancers.

Most often, the drug comes in a cream or lotion. It is usually applied to the

skin one or two times a day for several weeks. A drug called

fluorouracil

(5-FU) is used to treat basal cell and squamous cell cancers that are in the

top layer of the skin only. A drug called

imiquimod

also is used to treat basal

cell cancer only in the top layer of skin.

These drugs may cause your skin to turn red or swell. It also may itch, hurt,

ooze, or develop a rash. It may be sore or sensitive to the sun. These skin

changes usually go away after treatment is over. Topical chemotherapy usually

does not leave a scar. If healthy skin becomes too red or raw when the skin

cancer is treated, your doctor may stop treatment.

|

You may want to ask your doctor these questions about topical chemotherapy:

-

Do I need to take special care when I put chemotherapy on my skin? What do I

need to do? Will I be sensitive to the sun?

-

When will treatment start? When will it end?

|

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) uses a chemical along with a special light source,

such as a laser light, to kill cancer cells. The chemical is a

photosensitizing agent.

A cream is applied to the skin or the chemical is injected. It stays in

cancer cells longer than in normal cells. Several hours or days later, the

special light is focused on the growth. The chemical becomes active and

destroys nearby cancer cells.

PDT is used to treat cancer on or very near the surface of the skin.

The side effects of PDT are usually not serious. PDT may cause burning or

stinging pain. It also may cause burns, swelling, or redness. It may scar

healthy tissue near the growth. If you have PDT, you will need to avoid direct

sunlight and bright indoor light for at least 6 weeks after treatment.

The NCI fact sheet "Photodynamic Therapy for Cancer: Questions and Answers 9" has

more information.

|

You may want to ask your doctor these questions about PDT:

-

Will I need to stay in the hospital while the chemical is in my body?

-

Will I need to have the treatment more than once?

|

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) uses high-energy rays to kill

cancer cells. The rays come from a large machine outside the body. They affect

cells only in the treated area. This treatment is given at a hospital or clinic

in one dose or many doses over several weeks.

Radiation is not a common treatment for skin cancer. But it may be used for

skin cancer in areas where surgery could be difficult or leave a bad scar. You

may have this treatment if you have a growth on your eyelid, ear, or nose. It

also may be used if the cancer comes back after surgery to remove it.

Side effects depend mainly on the dose of radiation and the part of your body

that is treated. During treatment your skin in the treated area may become red,

dry, and tender. Your doctor can suggest ways to relieve the side effects of

radiation therapy. Also, the NCI booklet

Radiation Therapy and You: A Guide to

Self-Help During Cancer Treatment 10 offers more information.

|

You may want to ask your doctor these questions about radiation therapy:

-

How will I feel after the radiation?

-

Am I likely to have infection, swelling, blistering, or bleeding, or to get a scar

in the treated area?

-

How should I take care of the treated area?

|

Follow-up Care

Follow-up care after treatment for skin cancer is important. Your doctor will

monitor your recovery and check for new skin cancer. New skin cancers are more

common than having a treated skin cancer spread. Regular checkups help ensure

that any changes in your health are noted and treated if needed. Between

scheduled visits, you should check your skin regularly. You will find a guide

for checking your skin below 4. You

should contact the doctor if you notice anything unusual. It also is important

to follow your doctor's advice about how to reduce your risk of developing skin

cancer again.

Facing Forward Series: Life After Cancer Treatment 11 is an NCI booklet for people

who have completed their treatment. It answers questions about follow-up care

and other concerns. It has tips for making the best use of medical visits. It

also suggests ways to talk with the doctor about creating a plan of action for

your recovery and future health.

Sources of Support

Skin cancer has a better

prognosis,

or outcome, than most other types of

cancer. Still, learning you have any type of cancer can be upsetting. You may

worry about treatments, managing side effects, and medical bills. Doctors,

nurses, and other members of the health care team can answer your questions.

Meeting with a social worker, counselor, or member of the clergy can be helpful

if you want to talk about your feelings or concerns. Often, a social worker can

suggest resources for financial aid, transportation, or emotional support.

Support groups also can help. In these groups, patients or their family members

meet with other patients or their families to share what they have learned

about coping with cancer and the effects of treatment. Groups may offer support

in person, over the telephone, or online. You may want to talk with a member of

your health care team about finding a support group.

Information Specialists at 1-800-4-CANCER and at

LiveHelp 2 (http://www.cancer.gov/cis) can

help you locate programs, services, and publications. Also, you may want to see

the NCI fact sheet "National Organizations That Offer Services to People With

Cancer and Their Families 12."

The Promise of Cancer Research

Doctors are conducting clinical trials (research studies in which people

volunteer to take part).

Clinical trials are designed to answer important questions and to find out

whether new approaches are safe and effective. Research already has led to

advances, such as photodynamic therapy, and researchers continue to search for

better ways to prevent and treat skin cancer.

For basal cell cancer, researchers are studying gene changes that may be risk

factors for the disease. They also are comparing

biological therapy

with

surgery to treat basal cell cancer.

People who join clinical trials may be among the first to benefit if a new

approach is effective. And even if participants do not benefit directly, they

still make an important contribution by helping doctors learn more about the

disease and how to control it in other patients. Although clinical trials may

pose some risks, researchers do all they can to protect their patients.

If you are interested in being part of a clinical trial, talk with your doctor.

You may want to read the NCI booklet Taking Part in Cancer Treatment Research Studies 13. It explains how clinical trials are carried out and explains their possible benefits and risks.

NCI's Web site includes a section on clinical trials at http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials.

It has general information about clinical trials as well as detailed

information about specific ongoing studies of skin cancer. Information

Specialists at 1-800-4-CANCER or at

LiveHelp 2 at http://www.cancer.gov can

answer questions and provide information about clinical trials.

How To Do a Skin Self-Exam

Your doctor or nurse may suggest that you do a regular skin self-exam to check

for skin cancer, including

melanoma.

The best time to do this exam is after a shower or bath. You should check your

skin in a room with plenty of light. You should use a full-length mirror and a

hand-held mirror. It's best to begin by learning where your birthmarks, moles,

and other marks are and their usual look and feel.

Check for anything new:

-

New mole (that looks different from your other moles)

-

New red or darker color flaky patch that may be a little raised

-

New flesh-colored firm bump

-

Change in the size, shape, color, or feel of a mole

-

Sore that does not heal

Check yourself from head to toe. Don't forget to check your back, scalp,

genital area, and between your buttocks.

-

Look at your face, neck, ears, and scalp. You may want to use a comb or a blow

dryer to move your hair so that you can see better. You also may want to have a

relative or friend check through your hair. It may be hard to check your scalp

by yourself.

-

Look at the front and back of your body in the mirror. Then, raise your arms

and look at your left and right sides.

-

Bend your elbows. Look carefully at your fingernails, palms, forearms

(including the undersides), and upper arms.

-

Examine the back, front, and sides of your legs. Also look around your genital

area and between your buttocks.

-

Sit and closely examine your feet, including your toenails, your soles, and the

spaces between your toes.

By checking your skin regularly, you will learn what is normal for you. It may

be helpful to record the dates of your skin exams and to write notes about the

way your skin looks. If your doctor has taken photos of your skin, you can

compare your skin to the photos to help check for changes. If you find anything

unusual, see your doctor.

National Cancer Institute Information Resources

You may want more information for yourself, your family, and your doctor. The

following National Cancer Institute (NCI) services are available to help you.

Telephone

The NCI's Cancer Information Service (CIS) provides accurate, up-to-date

information on cancer to patients and their families, health professionals, and

the general public. Information Specialists translate the latest scientific

information into understandable language and respond in English, Spanish, or on

TTY equipment. Calls to the CIS are free.

Telephone: 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237)

TTY: 1-800-332-8615

Internet

The NCI's Web site (http://www.cancer.gov) provides information

from numerous NCI sources. It offers current information on cancer prevention,

screening, diagnosis, treatment, genetics, supportive care, and ongoing

clinical trials. It has information about NCI's research programs and funding

opportunities, cancer statistics, and the Institute itself. Information

Specialists provide live, online assistance through

LiveHelp 2.

National Cancer Institute Publications

National Cancer Institute (NCI) publications can be ordered by writing to the

address below:

Publications Ordering Service

National Cancer Institute

Suite 3035A

6116 Executive Boulevard, MSC 8322

Bethesda, MD 20892-8322

Many NCI publications can be viewed, downloaded, and ordered from

http://www.cancer.gov/publications 14 on the Internet. In addition,

people in the United States and its territories may order these and other NCI

publications by calling the NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-4-CANCER.

Booklets About Skin Changes and Skin Cancer

What You Need To Know

About™ Skin Cancer 15

What You Need To

Know About™ Melanoma 1

What

You Need To Know About™ Moles and Dysplastic Nevi 16

Booklets and Fact Sheets About Cancer Treatment and Support

Radiation Therapy and You: A Guide to Self-Help During Cancer Treatment 10

(also available in Spanish: La radioterapia y usted: una guía de autoayuda

durante el tratamiento del cáncer)

Biological Therapy: Treatments That Use Your Immune System to Fight

Cancer

Eating Hints for Cancer Patients: Before, During & After Treatment 17

(also available in Spanish: Consejos de alimentación para pacientes con cáncer:

antes, durante y después del tratamiento)

Understanding Cancer Pain 18 (also available in Spanish:

El dolor

relacionado con el cáncer 19)

Pain Control: A Guide for People with Cancer and Their Families 20 (also

available in Spanish: Control del dolor: guía para las personas con cáncer y

sus familias)

Get Relief from Cancer Pain

Thinking About Complementary and Alternative Medicine: A Guide for People with Cancer 21

"Biological Therapies for Cancer: Questions and Answers 22" (also available in

Spanish: "Terapias biológicas: el uso del sistema inmune para tratar el

cáncer 23")

"How To Find a Doctor or Treatment Facility If You Have Cancer 6" (also available

in Spanish: "Cómo encontrar a un doctor o un establecimiento de tratamiento si

usted tiene cáncer 24")

"Understanding Prognosis and Cancer Statistics 25" (also available in Spanish:

" 26La

interpretación de los pronósticos y las estadísticas del cáncer")

"National Organizations That Offer Services to People With Cancer and Their

Families 12" (also available in Spanish: "Organizaciones nacionales que brindan

servicios a las personas con cáncer y a sus familias 27")

"How To Find Resources in Your Own Community If You Have Cancer 28" (also

available in Spanish: "Cómo encontrar recursos en su comunidad si usted tiene

cáncer 29")

"Cryosurgery in Cancer Treatment: Questions and Answers 7"

"Photodynamic Therapy for Cancer: Questions and Answers 9"

"Lasers in Cancer Treatment: Questions and Answers 8"

Publications About Living With Cancer

Advanced Cancer: Living Each Day 30

Facing Forward Series: Life After

Cancer Treatment 11 (also available in Spanish:

Siga adelante: la vida después del tratamiento del cáncer 31)

Facing Forward Series: Ways You Can Make a

Difference in Cancer 32

Taking Time: Support for People with Cancer and

the People Who Care About Them 33

When Cancer Recurs: Meeting the Challenge 34

Publications About Clinical Trials

Taking Part in Cancer Treatment Research Studies 13

Taking Part in

Clinical Trials: Cancer Prevention Studies: What Participants Need To Know 35

(also available in Spanish: La participación en los estudios

clínicos: estudios para la prevención del cáncer)

|