Headline Archives |

|||||||||||

| FBI 100 The Lindbergh Kidnapping |

|||||||||||

| 03/03/08 | |||||||||||

|

Part 3 of our history series commemorating the FBI’s 100th anniversary in 2008. On a beautiful 390-acre estate on the rural outskirts of Hopewell, New Jersey, Charles Lindbergh and his wife Anne hoped to stay out of the constant glare of the media spotlight in the years following the aviator’s historic non-stop flight across the Atlantic. It was not to be. On March 1, 1932—76 years ago this month—a crime took place that stunned the nation and made the Lindberghs and their ensuing tragedy front-page news for months to come. It happened quickly and without warning. At around 9 p.m., the couple’s 20-month-old son was sleeping in his nursery on the second floor when someone leaned a ladder against the house, climbed through a window, and made off with the boy. The kidnapping was discovered about an hour later, along with a ransom note demanding $50,000. A massive investigation was launched, led by the New Jersey State Police. A dozen more ransom notes followed, including one that led to a meeting where Dr. John Condon, representing the Lindbergh family, paid a mysterious man named “John” $50,000 in gold certificates for the safe return of the child. But on May 12, 1932, the boy’s body was discovered less than five miles from the Lindbergh home. The boy had apparently been killed by a blow to the head shortly after the kidnapping.

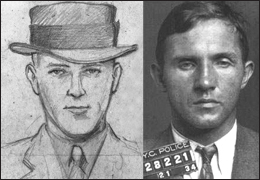

The Bureau was involved in the case almost from the beginning, offering any and all help to the New Jersey State Police. In the early days of the case, kidnapping was not a federal crime. A day after the boy’s remains were found, though, President Herbert Hoover ordered all national investigative agencies to help state authorities, with the Bureau taking the federal lead. In the coming months, the Bureau left no investigative stone unturned. We followed thousands of leads, including a number of bogus reports that spawned cases of their own. Working with Dr. Condon and others, we developed a likeness of “John” and a profile of his character and education. And through our new scientific crime lab in Washington, we carefully studied the handwriting in the ransom notes, concluding the author was German. A break in the case came from the ransom money. On May 2, 1933, nearly 300 gold certificates matching the ransom money were reported as deposited, but no useful information was uncovered from this lead. On August 20, 1934, 16 more certificates were found, and through painstaking investigative legwork investigators closed in on an area in New York City where the bills were circulating and developed a description of the suspect, which closely resembled our portrait of “John.” Less than a month later, a 10-dollar ransom certificate was traced to a gas station, where an alert attendant had written down the license plate of a car used by the man who had cashed the money. The license was traced to Bruno Richard Hauptmann, a German carpenter living in the Bronx. He was arrested on September 19, 1934.

The evidence pointed to Hauptmann as the culprit. He had more ransom money in his home. His handwriting matched that on the ransom notes. His car was similar to one sighted near the Lindbergh home. His tools were matched to tool marks on the ladder at the crime scene. In the end, he was convicted of the crime. For the Bureau, the case was a significant one. It demonstrated our growing scientific approach to solving crimes and was one of the earliest success stories of our new crime lab. And in response to the tragedy, Congress put the Bureau in the business of solving kidnappings, which we’ve been doing ever since. To learn more about the investigation, see our Famous Cases write-up.

FBI 100 Series:

- Part 1: An Odd Couple of Crime - Part 2: First Strike: Global Terror in America - More History stories |

|

|

|

|

|