Introduction to the Prostate

Prostate Changes That Are Not Cancer

Prostate Cancer

Talking to Your Doctor

Types of Tests

For More Information

Introduction to the Prostate

You may be reading this booklet because you are having prostate

problems. The booklet can help answer your questions about

prostate changes that happen with age, such as:

- What are common prostate changes?

- How are these changes treated?

- What do I need to know about testing for prostate

changes, including cancer?

This booklet can give you basic information about common

prostate changes. If you are making decisions about prostate

cancer treatment, there are other resources available. See the For

More Information 1 section.

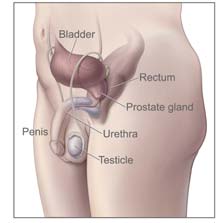

The

prostate

is a small gland in men. It is part of the male

reproductive system.

The prostate is about

the size and shape of

a walnut. It sits low

in the

pelvis, below

the

bladder

and

just in front of the

rectum. The

prostate helps make

semen, the milky

fluid that carries

sperm

from the

testicles

through

the

penis

when a

man

ejaculates.

The prostate surrounds part of the

urethra, a tube that carries

urine

out of the bladder and through the penis.

The prostate gland surrounds the tube (urethra) that passes urine.

This can be a source of problems as a man ages because:

- The prostate tends to grow bigger with age and may

squeeze the urethra (see drawing 2) or

- A

tumor

can make the prostate bigger

These changes, or an infection, can cause problems passing urine.

Sometimes men in their 30s and 40s may begin to have these

urinary

symptoms and need medical attention. For others,

symptoms aren't noticed until much later in life. Be sure to tell

your doctor if you have any urinary symptoms.

|

Tell your doctor if you:

|

- Are passing urine more during the day

- Have an urgent need to pass urine

- Have less urine flow

- Feel burning when you pass urine

- Need to get up many times during the night to

pass urine

|

Growing older raises your risk of prostate problems. The three

most common prostate problems are:

One change does not lead to another. For example, having

prostatitis or an enlarged prostate does not raise your chance of

prostate cancer. It is also possible for you to have more than one

condition at the same time.

|

Most men have prostate changes that are not

cancer. |

Abnormal findings from any of these tests can help diagnose a

problem and suggest the next steps to take:

- DRE (digital rectal exam)--a test to feel the prostate

- PSA (prostate-specific antigen) test--a blood test

- Biopsy--a test to check for cancer

See the Types of Tests 3 section.

Prostate Changes That Are Not Cancer

Prostatitis (pronounced "PRAH-stuh-TYE-tis") is an inflammation or

infection of the prostate gland. It affects at least half of all men at

some time in their lives. Having this condition does not increase

your risk of any other prostate disease.

| Prostatitis Symptoms |

- Trouble passing urine or pain when passing urine

- A burning or stinging feeling when passing urine

- Strong, frequent urge to pass urine, even when there

is only a small amount of urine

- Chills and high fever

- Low back pain or body aches

- Pain low in the belly, groin, or behind the

scrotum

- Rectal pressure or pain

- Urethral discharge with bowel movements

-

Genital

and rectal throbbing

- Sexual problems and loss of sex drive

- Blocked urine

- Painful ejaculation (sexual climax)

|

Prostatitis is not contagious. It is not spread through sexual

contact. Your partner cannot catch this infection from you.

Several tests, such as DRE and a urine test, can be done to see if

you have prostatitis. Getting the right diagnosis of your exact type

of prostatitis is the key to getting the best treatment. Even if you

have no symptoms, you should follow your doctor's suggestion to

complete treatment.

There are four types of prostatitis:

-

Acute bacterial prostatitis

This infection comes on suddenly (acute) and is caused by

bacteria. Symptoms include severe chills and fever. There is often

blood in the urine. You must go to the doctor's office or

emergency room for treatment. It's the least common of the four

types, yet it's the easiest to diagnose and treat.

|

Treatment: | |

Most cases can be cured with a high dose of

antibiotics, taken for 7 to 14 days, and then lower

doses for several weeks. You may also need drugs to

help with pain or discomfort.

|

-

Chronic bacterial prostatitis

Also caused by bacteria, this condition doesn't come on suddenly,

but it can be bothersome. The only symptom you may have is

bladder infections that keep coming back. The cause may be a

defect in the prostate that lets bacteria collect in the urinary tract.

|

Treatment: | |

Antibiotic treatment over a longer period of time is

best for this type. Treatment lasts from 4 to 12 weeks.

This type of treatment clears up about 60 percent of

cases. Long-term, low-dose antibiotics may help

relieve symptoms in cases that won't clear up.

|

-

Chronic prostatitis or chronic pelvic pain

syndrome

This disorder is the most common but least understood form of

the disease. Found in men of any age from late teens to elderly, its

symptoms go away and then return without warning. There can

be pain or discomfort in the groin or bladder area.

|

Treatment: | |

There are several different treatments for this

problem, based on your symptoms. These include

antibiotics and other medicines, such as

alpha-blockers.

Alpha-blockers relax muscle tissue in the

prostate to make passing urine easier.

|

-

Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis

You usually don't have symptoms with this condition. It is often

found when your doctor is looking for other conditions like

infertility

or prostate cancer. If you have this problem, often

your PSA test (see The PSA Test 4) will show a higher number than

normal. It does not necessarily mean that you have cancer.

|

Treatment: | |

Men with this condition are usually given antibiotics

for 4 to 6 weeks, and then have another PSA test.

|

"Changes happen so slowly that you don't

even realize they're happening."

BPH stands for benign prostatic hyperplasia (pronounced "be-NINE

prah-STAT-ik HY-per-PLAY-zha").

Benign means "not cancer," and hyperplasia means too much

growth. The result is that the prostate becomes enlarged. BPH is

not linked to cancer and does not raise your chances of getting

prostate cancer--yet the symptoms for BPH and prostate cancer

can be similar.

| BPH Symptoms |

BPH symptoms usually start after the age of 50.

They can include:

- Trouble starting a urine stream or making more than a

dribble

- Passing urine often, especially at night

- Feeling that the bladder has not fully emptied

- A strong or sudden urge to pass urine

- Weak or slow urine stream

- Stopping and starting again several times while passing urine

- Pushing or straining to begin passing urine

At its worst, BPH can lead to:

- A weak bladder

- Backflow of urine causing bladder or kidney infections

- Complete block in the flow of urine

- Kidney failure

|

BPH affects most men as they get older. It can lead to urinary

problems like those with prostatitis. By age 60, many men have

signs of BPH. By age 70, almost all men have some prostate

enlargement.

The prostate starts out about the size of a walnut. By the time a

man is 40, it may have grown slightly larger, to the size of an

apricot. By age 60, it may be the size of a lemon.

As a normal part of aging, the prostate enlarges and can press

against the bladder and the urethra. This can slow down or block

urine flow. Some men might find it hard to start a urine stream,

even though they feel the need to go. Once the urine stream has

started, it may be hard to stop. Other men may feel like they need

to pass urine all the time or are awakened during sleep with the

sudden need to pass urine.

Early BPH symptoms take many years to turn into bothersome

problems. These early symptoms are a cue to see your doctor.

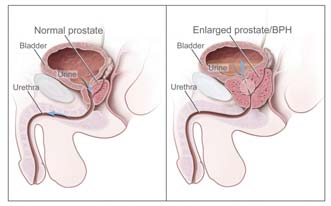

Urine flow of normal (left) and enlarged prostate (right). In diagram on

the left, urine flows freely. On the right, urine flow is affected because of

the prostate pressing on the bladder and urethra.

About half the men with BPH eventually have symptoms that are

bothersome enough to need treatment. BPH cannot be cured, but

drugs or surgery can often relieve its symptoms. BPH symptoms

do not always grow worse.

There are three ways to manage BPH:

- Watchful waiting (regular follow-up with your doctor)

- Drug therapy

- Surgery

Talk with your doctor about the best choice for you. Your

symptoms may change over time, so be sure to tell your doctor

about any new changes.

Watchful waiting

Men with mild symptoms of BPH who do not find them

bothersome often choose this approach.

Watchful waiting means getting annual checkups. The checkups

can include DREs and other tests (see "Types of Tests 3"). Treatment is

started only if symptoms become too much of a problem.

If you choose to live with symptoms, these simple steps can help:

- Limit drinking in the evening, especially drinks with

alcohol or caffeine.

- Empty the bladder all the way when you pass urine.

- Use the restroom often. Don't wait for long periods

without passing urine.

"My doctor and I decide visit by visit about

how long I should stay on watchful waiting

for my BPH.

Some medications can make BPH symptoms worse, so talk with

your doctor or pharmacist about any medicines you are taking

such as:

- Over-the-counter cold and cough medicines (especially

antihistamines)

- Tranquilizers

-

Antidepressants

- Blood pressure medicine

Drug therapy

Millions of American men with mild-to-moderate BPH symptoms

have chosen prescription drugs over surgery since the early 1990s.

There are two main types of drugs used. One type relaxes muscles

near the prostate while the other type shrinks the prostate gland.

There is evidence that shows that taking both drugs together may

work best to keep BPH symptoms from getting worse.

Alpha-blockers

These drugs help relax muscles near the prostate to relieve pressure

and let urine flow more freely, but they don't shrink the size of the

prostate. For many men, the drug can improve urine flow and

reduce symptoms within days. Possible side effects include

dizziness, headache, and fatigue.

5 alpha-reductase inhibitor

This drug, known as

finasteride, shrinks the prostate. It relieves

symptoms by blocking an

enzyme

that acts on the male

hormone, testosterone, to boost organ growth. When the

enzyme

is blocked, growth slows down. This helps shrink the prostate,

reduce blockage, and limit the need for surgery.

Taking this drug for at least 6 months to 1 year can increase urine

flow and reduce your symptoms. It seems to work best for men

with very large prostates. You must continue to take the drug to

prevent symptoms from coming back.

This drug is also used to treat baldness in men. It can cause these

side effects in a small percentage of men:

- Decreased interest in sex

- Trouble getting or keeping an

erection

- Smaller amount of semen with ejaculation

It's important to note that taking this drug can lower your PSA test

levels. There is also evidence that finasteride lowers the risk of

getting prostate cancer, but whether it lowers the risk of dying

from prostate cancer is still unclear.

| BPH Medications |

| Category |

Activity |

Generic Name |

Brand Name |

| Alpha-blockers |

Relax muscles

near prostate |

doxazosin

tamsulosin

terazosin

prazosin

|

Cardura

Flomax

Hytrin

Minipres

|

| 5 alphareductase

inhibitor |

Slows prostate growth, shrinks

prostate |

finasteride |

Proscar or

Propecia |

BPH surgery

The number of prostate surgeries has gone down over the years.

But operations for BPH are still one of the most common surgeries

for American men. Surgery is used when symptoms are severe or

drug therapy has not worked well.

Types of surgeries include:

-

TURP (transurethral resection of the prostate) is the most

common surgery for BPH. It accounts for 90 percent of all

BPH surgeries. It takes about 90 minutes. The doctor passes

an instrument through the urethra and trims away extra

prostate tissue. A

spinal block

is used to numb the area.

Tissue is sent to the laboratory to check for prostate cancer.

TURP generally avoids the two main dangers linked to other

prostate surgeries:

- Incontinence (not being able to hold in urine)

- Impotence (not being able to have an erection)

The recovery period for TURP is much shorter as well.

-

TUIP (transurethral incision of the prostate) is similar to

TURP. It is used on slightly enlarged prostate glands. The

surgeon places one or two small cuts in the prostate. This

relieves pressure without trimming away tissue. It has a low

risk of side effects. Like TURP, this treatment helps with urine

flow by widening the urethra.

-

TUNA (transurethral needle ablation) burns away excess

prostate tissue using radio waves. It helps with urine flow,

relieves symptoms, and may have fewer side effects than TURP.

Most men need a

catheter

to drain urine for a period of time

after the procedure.

-

TUMT (transurethral microwave thermotherapy) uses

microwaves sent through a catheter to destroy excess prostate

tissue. This can be an option for men who should not have

major surgery because they have other medical problems.

-

TUVP (transurethral electroevaporation of the prostate)

uses electrical current to vaporize prostate tissue.

-

Open prostatectomy means the surgeon removes the prostate

through a cut in the lower abdomen. This is done only in very

rare cases when obstruction is severe, the prostate is very large,

or other procedures can't be done. General or spinal

anesthesia is used and a catheter remains for 3 to 7 days after

the surgery. This surgery carries a higher risk of complications

than medical treatment. Tissue is sent to the laboratory to

check for prostate cancer.

Be sure to discuss options with your doctor and ask about the

potential short- and long-term benefits and risks with each

procedure. For a list of questions to ask, see

Checklist of Questions for Your Doctor 5.

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer means that cancer cells form in the tissues of the

prostate. It is the most common cancer in American men after

skin cancer.

Prostate cancer tends to grow slowly compared with most other

cancers. Cell changes may begin 10, 20, or 30 years before a

tumor gets big enough to cause symptoms. Eventually, cancer

cells may spread

(metastasize)

throughout the body. By the time

symptoms appear, the cancer may be more advanced.

By age 50, very few men have symptoms of prostate cancer, yet

some

precancerous

or cancerous cells are present. More than

half of all American men have some cancer in their prostate glands

by the age of 80.

Most of these cancers never pose a problem. They either give no

signs or symptoms or never become a serious threat to health.

A much smaller percentage of men are actually treated for prostate

cancer. Most men with prostate cancer do not die from this disease.

- About 16 percent of American men are diagnosed with

prostate cancer at some point in their lives.

- Eight percent have serious symptoms.

- Three percent die of the disease.

"When I first learned I might have a prostate

problem, I was afraid it was cancer."

Prostate cancer can sit quietly for years. That means most men

with the disease have no obvious symptoms. When symptoms

finally appear, they may be a lot like the symptoms of BPH.

| Prostate Cancer Symptoms |

- Trouble passing urine

- Frequent urge to pass urine, especially at night

- Weak or interrupted urine stream

- Pain or burning when passing urine

- Blood in the urine or semen

- Painful ejaculation

- Nagging pain in the back, hips, or pelvis

|

Prostate cancer can spread to the

lymph nodes

of the pelvis.

Or it may spread throughout the body. It tends to spread to the

bones. So bone pain, especially in the back, can be another

symptom.

There are some risk factors linked to prostate cancer. A risk factor

is something that can raise your chances of having a problem or

disease. Having one or more risk factors doesn't mean that you

will get prostate cancer. It just means that your risk of disease is

greater.

- Age. Being 50 or older increases risk of prostate cancer.

- Race. African-American men are at highest risk of prostate

cancer--it tends to start at younger ages and grows faster than

in men of other races. After African-American men, it is most

common among white men, followed by Hispanic and Native

American men. Asian-American men have the lowest rates of

prostate cancer. Aside from race, all men can have other

prostate cancer risk factors (aging, family history, and diet).

See the

For More Information 1 section to request the booklet

about African-American men and prostate cancer screening.

- Family history. Prostate cancer risk is 2 to 3 times higher for

men whose fathers or brothers have had the disease. For

example, risk is about 10 times higher for a man who has 3

immediate family members with prostate cancer. The younger

a man is when he has prostate cancer, the greater the risk for

his male family members. Prostate cancer risk also appears to

be slightly higher for men whose mothers or sisters have had

breast cancer.

- Diet. The risk of prostate cancer seems to be higher for men

eating high-fat diets with few fruits and vegetables.

National research studies are looking at how prostate cancer can be

prevented. There is some proof that the drug finasteride lowers

your risk of getting prostate cancer, but whether it decreases the

risk of dying of prostate cancer is still unclear.

To find out more, see the

For More Information 1 section.

| Prostate Cancer Screening |

Screening means testing for cancer before you have any

symptoms. A screening test can often help find cancer at an

early stage. When found early, cancer is less likely to have

spread and may be easier to treat. By the time symptoms

appear, the cancer may have started to spread. Remember,

even if your doctor suggests prostate cancer screening, this

doesn't necessarily mean that you have cancer.

Screening tests are most useful when they have been proven to

find cancer early and lower a person's chance of dying from

cancer. For prostate cancer, doctors don't yet know these

answers and more research is being done.

-

Large research studies, with thousands of men, are going on

now to study prostate cancer screening. The National

Cancer Institute is studying the combination of PSA testing

and DRE as a way to get more accurate results.

-

Some cancers never cause symptoms or become lifethreatening.

If they are found by a screening test, the

cancer may then be treated. For prostate cancer in its early

stages, it isn't known whether treatment would help you live

longer than if no treatment were given when a screening

test detects prostate cancer.

Talk with your doctor about your risk of prostate

cancer and your need for screening tests.

|

|

Talking to Your Doctor

Different kinds of doctors and other health care professionals

manage prostate health. They can help you find the best care,

answer your questions, and address your concerns. These health

care professionals include:

- Family doctors and internists

- Physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs)

-

Urologists, who are experts in diseases of the male

reproductive and urinary tract systems

- Urologic oncologists, who are experts in treating cancers of the

male urinary and reproductive systems such as prostate cancer

- Radiation oncologists, who use radiation therapy to kill cancer

cells

- Medical oncologists, who treat cancers with medications such

as hormone treatments and chemotherapy

-

Pathologists, who are doctors who find diseases by studying

cells and tissues under a microscope

View these professionals as your partners--expert advisors and

helpers in your health care. Talking openly with your doctors can

help you learn more about your prostate changes and the tests to

expect.

Types of Tests

These types of tests are most often used to check the prostate:

This first step lets your doctor hear and understand the "story" of

your prostate concerns. You'll be asked about whether you have

symptoms, how long you've had them, and how much they affect

your lifestyle. Your health history also includes any risk factors,

pain, fever, or trouble passing urine. You may be asked to give a

urine sample for testing.

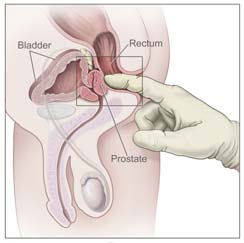

DRE is the standard way to check the prostate. With a gloved and

lubricated finger, your doctor feels the prostate from the rectum.

The test lasts about 10-15 seconds.

This exam checks for:

- The size, firmness, and texture of the prostate

- Any hard areas, lumps, or growth spreading beyond the

prostate

- Any pain caused by touching or pressing the prostate

The DRE allows the doctor to feel only one side of the prostate.

A PSA test is another way to help your doctor check your prostate.

PSA is a protein made by normal cells and prostate cancer cells. It

is found in the blood and can be measured with a blood test. PSA

tests are often used to follow men after prostate cancer treatment.

PSA testing is still being studied to see if finding cancer early

lowers the risk of dying from prostate cancer.

PSA levels can rise if a man has prostate cancer, but a high PSA is

not proof of cancer. Other things can also make PSA levels go up.

These may give a

false positive

test result. These include having

BPH or prostatitis, or if the prostate gland is disturbed in any way

(riding a bicycle or motorcycle, a DRE, orgasm within the past 24

hours, and prostate biopsy or surgery can disturb the prostate).

Also, some prostate glands naturally produce more PSA than

others. PSA levels go up with age. African-American men tend to

have higher PSA levels in general than men of other races.

Researchers are trying to find more answers about:

- The PSA test's ability to tell cancer from benign prostate

problems

- The best thing to do if a man has a high PSA level

For now, men and their doctors use PSA readings over time as a

guide to see if more follow-up is needed.

PSA levels are measured in terms of units per volume of fluid

tested. Doctors often use a score of 4

nanograms (ng)

or higher

as the trigger for further tests, such as a prostate biopsy.

Your doctor may monitor your PSA velocity, which means looking

at the rate of change in your PSA levels over time. Rapid increases

in PSA readings can suggest cancer. If you have a mildly elevated

PSA, you and your doctor may choose to check PSA levels on a

scheduled basis and watch for any change in the PSA velocity.

If your symptoms or test results suggest cancer, your doctor will

refer you to a specialist (a urologist) for a prostate biopsy. A

biopsy is usually done in the doctor's office.

For a biopsy, small tissue samples are taken directly from the

prostate. Your doctor will take samples from several areas of the

prostate gland. This can help lower the chance of missing any

areas of the gland that may have cancer cells. Like other cancers,

doctors can only diagnose prostate cancer by looking at tissue

under a microscope.

Most men who have biopsies after routine exams do not have cancer.

|

"There is no magic PSA level below which a man can be assured of

having no risk of prostate cancer nor above which a biopsy should

automatically be performed. A man's decision to have a prostate

biopsy requires a thoughtful discussion with his physician,

considering not only the PSA level, but also his other risk factors,

his overall health status, and how he perceives the risks and

benefits of early detection."

--Dr. Howard Parnes, Chief of the Prostate and Urologic Cancer Research Group,

Division of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute

|

A test that can help your doctor decide if you need a repeat biopsy

is called

free PSA. This test is used for men who have higher PSA

values. The test looks at a form of PSA in the blood. Free PSA is

linked to BPH but not cancer.

Free PSA is figured as a percentage of the total PSA:

- If both total PSA and free PSA are higher than normal, this

suggests BPH rather than cancer.

- If regular PSA is high but free PSA is not, cancer is more

likely. More testing should be done.

Free PSA may help tell what kind of prostate problem you have. It

can be a guide for you and your doctor to choose the right

treatment. You and your doctor should talk about your personal

risk and free PSA results. Then you can decide together whether to

have follow-up biopsies and, if so, how often.

A positive biopsy means prostate cancer is present. A pathologist

will check your biopsy sample for cancer cells and will give a

Gleason score. The Gleason score ranges from 2 to 10 and

describes how likely it is that a tumor will spread. The lower the

number, the less likely the tumor is aggressive and may spread.

Treatment options depend on the stage (or extent) of the cancer

(stages range from 1 to 4), Gleason score, PSA level, and your age

and general health. These items will be available from your doctor

and are listed on your pathology report.

Reaching a decision about treatment of your prostate cancer is a

complex process. Many men find it helpful to talk with their

doctors, family, friends, and other men who have faced similar

decisions. There are many organizations that can provide more

information and support to you, your partner, and family.

"While it's important to make your own decision

about cancer screening, everybody should

consider getting a second opinion before

getting something like a biopsy."

It is a good idea to get a copy of your pathology report

from your doctor and carry it with you as you talk with

your health care providers.

| Checklist of Questions for Your Doctor |

- What type of prostate problem do I have?

- Is more testing needed and what will it tell me?

- If I decide on watchful waiting, what changes in my

symptoms should I look for and how often should I

be tested?

- What type of treatment do you recommend for my prostate

problem?

- For men like me, has this treatment worked?

- How soon would I need to start treatment and how long

would it last?

- Do I need medicine and how long would I need to take it

before seeing improvement in my symptoms?

- What are the side effects of the medicine?

- Are there other medicines that could interfere with this

medication?

- If I need surgery, what are the benefits and risks?

- Would I have any side effects from surgery that could affect

my quality of life?

- Are these side effects temporary or permanent?

- How long is recovery time after surgery?

- Will I be able to fully return to normal?

- How will this affect my sex life?

- How often should I visit the doctor to monitor my condition?

|

|

For More Information

National Cancer Institute

You can find out more from these free NCI services.

Cancer Information Service (CIS)

Toll-free ................1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237)

TTY ........................1-800-332-8615

NCI Online ............www.cancer.gov

Chat Online ..........www.cancer.gov and click on

"Need Help? 6"

Free booklets that are available include:

Other Federal Resources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Toll-free ................1-888-842-6355

FAX ........................1-770-488-4760

E-mail ....................cancerinfo@cdc.gov

Online.................... 9www.cdc.gov/cancer/prostate/

Free booklets that are available include:

- Prostate Cancer Screening: A Decision Guide

- Prostate Cancer Screening: A Decision Guide for African Americans

Medicare

For more information about Medicare benefits, contact:

Toll-free ................1-800-MEDICARE (1-800-633-4227)

Online....................www.medicare.gov

National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information

Clearinghouse

Toll-free ................1-800-891-5390

Online....................www.niddk.nih.gov

|