About This Book

Questions and Answers About Radiation Therapy

External Beam Radiation Therapy

Internal Radiation Therapy

Your Feelings During Radiation Therapy

Radiation Therapy Side Effects

Radiation Therapy Side Effects At-A-Glance

Radiation Therapy Side Effects and Ways to Manage Them

Late Radiation Therapy Side Effects

Questions To Ask Your Doctor or Nurse

Lists of Foods and Liquids

Words To Know

Resources for Learning More

For More Information

About This Book

Radiation Therapy and You is written for you - someone

who is about to get or is now getting radiation therapy for

cancer. People who are close to you may also find this

book helpful.

This book is a guide that you can refer to throughout

radiation therapy. It has facts about radiation therapy and

side effects and describes how you can care for yourself

during and after treatment.

| Rather than read

this book from

beginning to end -

look at only those

sections you need

now. Later, you can

always read more.

|

This book covers:

Talk with your doctor and nurse about the information in this book. They may suggest

that you read certain sections or follow some of the tips. Since radiation therapy affects

people in different ways, they may also tell you that some of the information in this book

is not right for you.

Questions and Answers About Radiation Therapy

| What is radiation

therapy? | Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) is a cancer

treatment that uses high doses of radiation to kill cancer cells

and stop them from spreading. At low doses, radiation is used

as an x-ray to see inside your body and take pictures, such as

x-rays of your teeth or broken bones. Radiation used in

cancer treatment works in much the same way, except that it is

given at higher doses.

|

|

| How is radiation

therapy given? | Radiation therapy can be external beam (when a machine

outside your body aims radiation at cancer cells) or internal

(when radiation is put inside your body, in or near the cancer

cells). Sometimes people get both forms of radiation therapy.

To learn more about external beam radiation therapy, see

"External Beam Radiation Therapy" 2.

To learn more about internal radiation therapy, see

"Internal Beam Radiation Therapy" 3.

|

|

| Who gets

radiation therapy? | Many people with cancer need radiation therapy. In fact,

more than half (about 60 percent) of people with cancer get

radiation therapy. Sometimes, radiation therapy is the only

kind of cancer treatment people need.

|

|

| What does

radiation therapy

do to cancer cells? | Given in high doses, radiation kills or slows the growth of

cancer cells. Radiation therapy is used to:

- Treat cancer. Radiation can be used to cure, stop, or slow

the growth of cancer.

-

Reduce symptoms. When a cure is not possible, radiation

may be used to shrink cancer tumors in order to reduce

pressure. Radiation therapy used in this way can treat

problems such as pain, or it can prevent problems such as

blindness or loss of bowel and bladder control.

|

|

| How long does

radiation therapy

take to work? | Radiation therapy does not kill cancer cells right away. It takes

days or weeks of treatment before cancer cells start to die.

Then, cancer cells keep dying for weeks or months after

radiation therapy ends.

|

|

| What does

radiation therapy

do to healthy cells? | Radiation not only kills or slows the growth of cancer cells, it

can also affect nearby healthy cells. The healthy cells almost

always recover after treatment is over. But sometimes people

may have side effects that do not get better or are severe.

Doctors try to protect healthy cells during treatment by:

- Using as low a dose of radiation as possible. The

radiation dose is balanced between being high enough to

kill cancer cells yet low enough to limit damage to healthy

cells.

-

Spreading out treatment over time. You may get

radiation therapy once a day for several weeks or in smaller

doses twice a day. Spreading out the radiation dose allows

normal cells to recover while cancer cells die.

-

Aiming radiation at a precise part of your body. New

techniques, such as IMRT and

3-D conformal radiation

therapy, allow your doctor to aim higher doses of

radiation at your cancer while reducing the radiation to

nearby healthy tissue.

-

Using medicines. Some drugs can help protect certain

parts of your body, such as the salivary glands that make

saliva (spit).

|

|

| Does radiation

therapy hurt? | No, radiation therapy does not hurt while it is being given. But

the side effects that people may get from radiation therapy can

cause pain or discomfort. This book has a lot of information

about ways that you, your doctor, and your nurse can help

manage side effects.

|

|

| Is radiation

therapy used with

other types

of cancer

treatment? | Yes, radiation therapy is often used with other cancer

treatments. Here are some examples:

- Radiation therapy and surgery. Radiation may be given

before, during, or after surgery. Doctors may use radiation

to shrink the size of the cancer before surgery, or they

may use radiation after surgery to kill any cancer cells

that remain. Sometimes, radiation therapy is given

during surgery so that it goes straight to the cancer

without passing through the skin. This is called

intraoperative radiation.

-

Radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Radiation may be

given before, during, or after chemotherapy. Before or

during chemotherapy, radiation therapy can shrink the

cancer so that chemotherapy works better. Sometimes,

chemotherapy is given to help radiation therapy work

better. After chemotherapy, radiation therapy can be used

to kill any cancer cells that remain.

|

|

Who is on my

radiation therapy

team?

| Many people help with your radiation treatment and care. This

group of health care providers is often called the "radiation

therapy team." They work together to provide care that is just

right for you. Your radiation therapy team can include:

- Radiation oncologist. This is a doctor who specializes in

using radiation therapy to treat cancer. He or she

prescribes how much radiation you will receive, plans how

your treatment will be given, closely follows you during

your course of treatment 10, and prescribes care you may need

to help with side effects. He or she works closely with the

other doctors, nurses, and health care providers on your

team. After you are finished with radiation therapy, your

radiation oncologist will see you for follow-up visits.

During these visits, this doctor will check for

late side effects and assess how well the radiation has worked.

- Nurse practitioner. This is a nurse with advanced

training. He or she can take your medical history, do

physical exams, order tests, manage side effects, and closely

watch your response to treatment. After you are finished

with radiation therapy, your nurse practitioner may see

you for follow-up visits to check for late side effects and

assess how well the radiation has worked.

- Radiation nurse. This person provides nursing care during

radiation therapy, working with all the members of your

radiation therapy team. He or she will talk with you about

your radiation treatment and help you manage side effects.

- Radiation therapist. This person works with you during

each radiation therapy session. He or she positions you for

treatment and runs the machines to make sure you get the

dose of radiation prescribed by your radiation oncologist.

- Other health care providers. Your team may also include

a dietitian, physical therapist, social worker, and others.

- You. You are also part of the radiation therapy team.

Your role is to:

- Arrive on time for all radiation therapy sessions

- Ask questions and talk about your concerns

- Let someone on your radiation therapy team know

when you have side effects

- Tell your doctor or nurse if you are in pain

- Follow the advice of your doctors and nurses about

how to care for yourself at home, such as:

- Taking care of your skin

- Drinking liquids

- Eating foods that they suggest

- Keeping your weight the same

|

|

| You are the most important part of the radiation therapy team.

|

| Be sure to arrive on time for ALL

radiation therapy sessions.

|

|

| Is radiation

therapy expensive? | Yes, radiation therapy costs a lot of money. It uses complex

machines and involves the services of many health care

providers. The exact cost of your radiation therapy depends

on the cost of health care where you live, what kind of

radiation therapy you get, and how many treatments you need.

Talk with your health insurance company about what services

it will pay for. Most insurance plans pay for radiation therapy

for their members. To learn more, talk with the business office

where you get treatment. You can also contact the National

Cancer Institute's Cancer Information Service and ask for the

"Financial Assistance for Cancer Care" 11 fact sheet. See

"Resources for Learning More" 9

for ways to contact the National Cancer Institute.

|

|

| Should I follow

a special diet

while I am getting

radiation therapy? | Your body uses a lot of energy to heal during radiation

therapy. It is important that you eat enough calories and

protein to keep your weight the same during this time. Ask

your doctor or nurse if you need a special diet while you are

getting radiation therapy. You might also find it helpful to

speak with a dietitian.

To learn more about foods and drinks that are high in calories

or protein, see

"Foods and Drinks That Are High in Calories or Protein" 12. You may also want to read

Eating Hints 13, a book from the National Cancer Institute. You

can order a free copy online at www.cancer.gov/publications

or 1-800-4-CANCER. |

|

| Ask your doctor, nurse, or dietitian

if you need a special diet while

you are getting radiation therapy.

|

|

| Can I go to work

during radiation

therapy? | Some people are able to work full-time during radiation

therapy. Others can only work part-time or not at all. How

much you are able to work depends on how you feel. Ask your

doctor or nurse what you may expect based on the treatment

you are getting.

You are likely to feel well enough to work when you start

radiation therapy. As time goes on, do not be surprised if you

are more tired, have less energy, or feel weak. Once you have

finished your treatment, it may take a few weeks or many

months for you to feel better.

You may get to a point during your radiation therapy when

you feel too sick to work. Talk with your employer to find

out if you can go on medical leave 14. Make sure that your

health insurance will pay for treatment when you are on

medical leave. |

|

| What happens

when radiation

therapy is over? | Once you have finished radiation therapy, you will need

follow-up care for the rest of your life. Follow-up care refers

to checkups with your radiation oncologist or nurse

practitioner after your course of radiation therapy is over.

During these checkups, your doctor or nurse will see how well

the radiation therapy worked, check for other signs of cancer,

look for late side effects, and talk with you about your

treatment and care. Your doctor or nurse will:

- Examine you and review how you have been feeling. Your

doctor or nurse practitioner can prescribe medicine or

suggest other ways to treat any side effects you may have.

- Order lab and imaging tests. These may include blood

tests, x-rays, or CT, MRI, or PET scans.

-

Discuss treatment. Your doctor or nurse practitioner may

suggest that you have more treatment, such as extra

radiation treatments, chemotherapy, or both.

-

Answer your questions and respond to your concerns. It

may be helpful to write down your questions ahead of time

and bring them with you. You can find sample questions

in "Questions To Ask Your Doctor or Nurse" 6.

|

|

| After radiation

therapy is over,

what symptoms

should I

look for? | You have gone through a lot with cancer and radiation

therapy. Now you may be even more aware of your body and

how you feel each day. Pay attention to changes in your body

and let your doctor or nurse know if you have:

- A pain that does not go away

- New lumps, bumps, swellings, rashes, bruises, or bleeding

- Appetite changes, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation

- Weight loss that you cannot explain

- A fever, cough, or hoarseness that does not go away

- Any other symptoms that worry you

See "Resources for Learning More" 9 for ways to

learn more about radiation therapy. |

|

|

| Make a list of questions and problems

you want to discuss with your doctor or nurse.

Be sure to bring this list to your follow-up visits.

See "Questions To Ask Your Doctor or Nurse" 6

for sample questions.

|

|

External Beam Radiation Therapy

| What is external

beam radiation

therapy? |

External beam radiation therapy comes from a machine that

aims radiation at your cancer. The machine is large and may

be noisy. It does not touch you, but rotates around you,

sending radiation to your body from many directions.

External beam radiation therapy is a local treatment, meaning

that the radiation is aimed only at a specific part of your body.

For example, if you have lung cancer, you will get radiation to

your chest only and not the rest of your body.

External beam radiation therapy comes from a machine that aims

radiation at your cancer.

|

|

| How often will I

get external beam

radiation therapy? |

Most people get external beam radiation therapy once a day,

5 days a week, Monday through Friday. Treatment lasts for

2 to 10 weeks, depending on the type of cancer you have and

the goal of your treatment. The time between your first and

last radiation therapy sessions is called a course of treatment.

Radiation is sometimes given in smaller doses twice a day

(hyperfractionated radiation therapy). Your doctor may

prescribe this type of treatment if he or she feels that it will

work better. Although side effects may be more severe, there

may be fewer late side effects. Doctors are doing research to

see which types of cancer are best treated this way.

|

|

|

Where do I go for

external beam

radiation therapy?

|

Most of the time, you will get external beam radiation therapy

as an outpatient. This means that you will have treatment at a

clinic or radiation therapy center and will not have to stay in

the hospital.

|

|

What happens

before my first

external beam

radiation

treatment?

If you are getting radiation

to the head, you may need a

mask.

|

You will have a 1- to 2-hour meeting with your doctor or nurse

before you begin radiation therapy. At this time, you will have

a physical exam, talk about your medical history, and maybe

have imaging tests. Your doctor or nurse will discuss external

beam radiation therapy, its benefits and side effects, and ways

you can care for yourself during and after treatment. You can

then choose whether to have external beam radiation therapy.

If you agree to have external beam radiation therapy, you will

be scheduled for a treatment planning session called a

simulation. At this time:

- A radiation oncologist and radiation therapist will define

your treatment area (also called a treatment port or

treatment field). This refers to the places in your body that

will get radiation. You will be asked to lie very still while

x-rays or scans are taken to define the treatment area.

-

The radiation therapist will then put small marks (tattoos or

dots of colored ink) on your skin to mark the treatment

area. You will need these marks throughout the course of

radiation therapy. The radiation therapist will use them

each day to make sure you are in the correct position.

Tattoos are about the size of a freckle and will remain on

your skin for the rest of your life. Ink markings will fade

over time. Be careful not to remove them and make sure to

tell the radiation therapist if they fade or lose color.

- You may need a body mold. This is a plastic or plaster

form that helps keep you from moving during treatment. It

also helps make sure that you are in the exact same

position each day of treatment.

- If you are getting radiation to the head, you may need a

mask. The mask has air holes, and holes can be cut for

your eyes, nose, and mouth. It attaches to the table where

you will lie to receive your treatments. The mask helps

keep your head from moving so that you are in the exact

same position for each treatment.

If the body mold or mask makes you feel anxious, see

"Your Feelings During Radiation Therapy" 4

for ways to relax during treatment.

|

|

|

Tell your radiation therapist if your

ink marks begin to fade or lose color.

|

|

|

What should I

wear when I get

external beam

radiation therapy?

|

Wear clothes that are comfortable and made of soft fabric,

such as cotton. Choose clothes that are easy to take off, since

you may need to change into a hospital gown or show the area

that is being treated. Do not wear clothes that are tight, such

as close-fitting collars or waistbands, near your treatment area.

Also, do not wear jewelry, BAND-AIDS®, powder, lotion, or

deodorant in or near your treatment area, and do not use

deodorant soap before your treatment.

|

|

|

What happens

during treatment

sessions?

|

- You may be asked to change into a hospital gown or robe.

- You will go to a treatment room where you will receive

radiation.

- Depending on where your cancer is, you will either sit in a

chair or lie down on a treatment table. The radiation

therapist will use your body mold and skin marks to help

you get into position.

- You may see colored lights pointed at your skin marks.

These lights are harmless and help the therapist position

you for treatment each day.

- You will need to stay very still so the radiation goes to the

exact same place each time. You can breathe as you always

do and do not have to hold your breath.

The radiation therapist will leave the room just before your

treatment begins. He or she will go to a nearby room to

control the radiation machine and watch you on a TV screen

or through a window. You are not alone, even though it may

feel that way. The radiation therapist can see you on the

screen or through the window. He or she can hear and talk

with you through a speaker in your treatment room. Make

sure to tell the therapist if you feel sick or are uncomfortable.

He or she can stop the radiation machine at any time. You

cannot feel, hear, see, or smell radiation.

Your entire visit may last from 30 minutes to 1 hour. Most of

that time is spent setting you in the correct position. You will

get radiation for only 1 to 5 minutes. If you are getting IMRT,

your treatment may last longer. Your visit may also take longer

if your treatment team needs to take and review x-rays.

|

|

|

Your radiation therapist can see, hear, and

talk with you at all times while you are

getting external beam radiation therapy.

|

|

|

Will external beam

radiation therapy

make me

radioactive?

|

No, external beam radiation therapy does not make people

radioactive. You may safely be around other people, even

babies and young children.

|

|

How can I relax

during my

treatment sessions?

|

- Bring something to read or do while in the waiting room.

- Ask if you can listen to music or books on tape.

- Meditate, breathe deeply, use imagery, or find other ways

to relax. To learn more about ways to relax, see Facing

Forward: Life After Cancer Treatment 15, a book from the

National Cancer Institute. You can order a free copy at

www.cancer.gov/publications or 1-800-4-CANCER.

For ways to learn more about external beam radiation therapy,

see "Resources for Learning More" 9.

|

Internal Radiation Therapy

|

What is internal

radiation therapy?

|

Internal radiation therapy is a form of treatment where a

source of radiation is put inside your body. One form of

internal radiation therapy is called brachytherapy. In

brachytherapy, the radiation source is a solid in the form of

seeds, ribbons, or capsules, which are placed in your body in

or near the cancer cells. This allows treatment with a high

dose of radiation to a smaller part of your body. Internal

radiation can also be in a liquid form. You receive liquid

radiation by drinking it, by swallowing a pill, or through an IV.

Liquid radiation travels throughout your body, seeking out

and killing cancer cells.

Brachytherapy may be used with people who have cancers of

the head, neck, breast, uterus, cervix, prostate, gall bladder,

esophagus, eye, and lung. Liquid forms of internal radiation

are most often used with people who have thyroid cancer or

non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. You may also get internal

radiation along with other types of treatment, including

external beam radiation, chemotherapy, or surgery.

|

|

|

What happens

before my first

internal radiation

treatment?

|

You will have a 1- to 2-hour meeting with your doctor or

nurse before you begin internal radiation therapy. At this

time, you will have a physical exam, talk about your medical

history, and maybe have imaging tests. Your doctor will

discuss the type of internal radiation therapy that is best for

you, its benefits and side effects, and ways you can care for

yourself during and after treatment. You can then choose

whether to have internal radiation therapy.

|

|

|

How is

brachytherapy

put in place?

|

Most brachytherapy is put in place through a catheter, which

is a small, stretchy tube. Sometimes, it is put in place through

a larger device called an applicator 16. When you decide to have

brachytherapy, your doctor will place the catheter or applicator

into the part of your body that will be treated.

|

|

|

What happens

when the catheter

or applicator is

put in place?

|

You will most likely be in the hospital when your catheter or

applicator is put in place. Here is what to expect:

- You will either be put to sleep or the area where the

catheter or applicator goes will be numbed. This will help

prevent pain when it is put in.

-

Your doctor will place the catheter or applicator in your body.

- If you are awake, you may be asked to lie very still while

the catheter or applicator is put in place. If you feel any

discomfort, tell your doctor or nurse so he or she can give

you medicine to help manage the pain.

|

|

|

Tell your doctor or nurse if you are in pain.

|

|

|

What happens

after the catheter or

applicator is placed

in my body?

|

Once your treatment plan is complete, radiation will be placed

inside the catheter or applicator. The radiation source may be

kept in place for a few minutes, many days, or the rest of your

life. How long the radiation is in place depends on which type

of brachytherapy you get, your type of cancer, where the

cancer is in your body, your health, and other cancer

treatments you have had.

|

|

|

What are the types

of brachytherapy?

|

There are three types of brachytherapy:

- Low-dose rate (LDR) implants. In this type of

brachytherapy, radiation stays in place for 1 to 7 days. You

are likely to be in the hospital during this time. Once your

treatment is finished, your doctor will remove the

radiation sources and your catheter or applicator.

-

High-dose rate (HDR) implants. In this type of

brachytherapy, the radiation source is in place for 10 to 20

minutes at a time and then taken out. You may have

treatment twice a day for 2 to 5 days or once a week for

2 to 5 weeks. The schedule depends on your type of

cancer. During the course of treatment, your catheter or

applicator may stay in place, or it may be put in place

before each treatment. You may be in the hospital during

this time, or you may make daily trips to the hospital to

have the radiation source put in place. Like LDR implants,

your doctor will remove your catheter or applicator once

you have finished treatment.

-

Permanent implants. After the radiation source is put in

place, the catheter is removed. The implants always stay in

your body, while the radiation gets weaker each day. You

may need to limit your time around other people when the

radiation is first put in place. Be extra careful not to spend

time with children or pregnant women. As time goes by,

almost all the radiation will go away, even though the

implant stays in your body.

|

|

What happens

while the radiation

is in place?

|

- Your body will give off radiation once the radiation source is

in place. With brachytherapy, your body fluids (urine,

sweat, and saliva) will not give off radiation. With liquid

radiation, your body fluids will give off radiation for a while.

- Your doctor or nurse will talk with you about safety

measures that you need to take.

- If the radiation you receive is a very high dose, safety

measures may include:

- Staying in a private hospital room to protect others

from radiation coming from your body

- Being treated quickly by nurses and other hospital staff.

They will provide all the care you need, but they may

stand at a distance and talk with you from the doorway

to your room.

- Your visitors will also need to follow safety measures,

which may include:

- Not being allowed to visit when the radiation is first

put in

- Needing to check with the hospital staff before they go

to your room

- Keeping visits short (30 minutes or less each day). The

length of visits depends on the type of radiation being

used and the part of your body being treated.

- Standing by the doorway rather than going into your

hospital room

- Not having visits from children younger than 18 and

pregnant women

You may also need to follow safety measures once you leave

the hospital, such as not spending much time with other

people. Your doctor or nurse will talk with you about the

safety measures you should follow when you go home.

|

|

|

What happens

when the catheter

is taken out after

treatment with

LDR or HDR

implants?

|

- You will get medicine for pain before the catheter or

applicator is removed.

-

The area where the catheter or applicator was might be

tender for a few months.

- There is no radiation in your body after the catheter or

applicator is removed. It is safe for people to be near

you - even young children and pregnant women.

-

For 1 to 2 weeks, you may need to limit activities that take

a lot of effort. Ask your doctor what kinds of activities are

safe for you.

For ways to learn more about internal radiation therapy, see

"Resources for Learning More" 9.

|

|

Your Feelings During Radiation Therapy

At some point during radiation therapy, you may feel:

- Anxious

- Depressed

- Afraid

- Angry

- Frustrated

- Helpless

- Alone

It is normal to have these kinds of feelings. Living with cancer

and going through treatment is stressful. You may also feel

fatigue, which can make it harder to cope with these feelings.

|

Having cancer and

going through treatment

is stressful.

|

|

How can I cope

with my feelings

during radiation

therapy?

|

There are many things you can do to cope with your feelings

during treatment. Here are some things that have worked for

other people:

- Relax and meditate. You might try thinking of yourself in

a favorite place, breathing slowly while paying attention to

each breath, or listening to soothing music. These kinds of

activities can help you feel calmer and less stressed.

-

Exercise. Many people find that light exercise (such as

walking, biking, yoga, or water aerobics) helps them feel

better. Talk with your doctor or nurse about types of

exercise that you can do.

-

Talk with others. Talk about your feelings with someone

you trust. You may choose a close friend, family member,

chaplain, nurse, social worker, or psychologist. You may

also find it helpful to talk to someone else who is going

through radiation therapy.

-

Join a support group. Cancer support groups are

meetings for people with cancer. These groups allow you to

meet others facing the same problems. You will have a

chance to talk about your feelings and listen to other people

talk about theirs. You can learn how others cope with

cancer, radiation therapy, and side effects. Your doctor,

nurse, or social worker can tell you about support groups

near where you live. Some support groups also meet over

the Internet, which can be helpful if you cannot travel or

find a meeting in your area.

-

Talk to your doctor or nurse about things that worry or

upset you. You may want to ask about seeing a counselor.

Your doctor may also suggest that you take medicine if you

find it very hard to cope with these feelings.

|

|

|

Ways to

Learn More

|

To learn more about ways to cope with your feelings, read

Taking Time: Support for People With Cancer 17, a book from the

National Cancer Institute. You can get a free copy at

www.cancer.gov/publications or 1-800-4-CANCER.

National Cancer Institute

Cancer Information Service

|

CancerCare, Inc.

| Toll-free: |

|

1-800-813-HOPE (1-800-813-4673) |

| E-mail: |

|

info@cancercare.org |

| Online: |

|

www.cancercare.org |

| Offers free support, information, financial assistance, and

practical help to people with cancer and their loved ones. |

The Wellness Community

|

|

Radiation Therapy Side Effects

|

Side effects are problems that can happen as a result of

treatment. They may happen with radiation therapy because

the high doses of radiation used to kill cancer cells can also

damage healthy cells in the treatment area. Side effects are

different for each person. Some people have many side effects;

others have hardly any. Side effects may be more severe if you

also receive chemotherapy before, during, or after your

radiation therapy.

Talk to your radiation therapy team about your chances of

having side effects. The team will watch you closely and ask if

you notice any problems. If you do have side effects or other

problems, your doctor or nurse will talk with you about ways to

manage them.

|

|

|

Common

Side Effects

|

Many people who get radiation therapy have skin changes and

some fatigue. Other side effects depend on the part of your

body being treated.

Skin changes may include dryness, itching, peeling, or blistering.

These changes occur because radiation therapy damages healthy

skin cells in the treatment area. You will need to take special

care of your skin during radiation therapy. To learn more,

see "Skin Changes" 18.

Fatigue is often described as feeling worn out or exhausted.

There are many ways to manage fatigue. To learn more,

see "Fatigue" 19.

Depending on the part of your body being treated, you may

also have:

- Diarrhea

- Hair loss in the treatment area

- Mouth problems

- Nausea and vomiting

- Sexual changes

- Swelling

- Trouble swallowing

- Urinary and bladder changes

Most of these side effects go away within 2 months after

radiation therapy is finished.

Late side effects may first occur 6 or more months after

radiation therapy is over. They vary by the part of your body

that was treated and the dose of radiation you received. Late

side effects may include infertility, joint problems,

lymphedema, mouth problems, and secondary cancer.

Everyone is different, so talk to your doctor or nurse about

whether you might have late side effects and what signs to look

for. See "Late Radiation Therapy Side Effects" 20 for more information on late side effects.

"Radiation Therapy Side Effects and Ways to Manage Them" 21 explains each side effect in more detail

and includes ways you and your doctor or nurse can help

manage them.

|

|

Radiation Therapy Side Effects At-A-Glance

Radiation therapy side effects depend on the part of your body

being treated. You can use the chart

below

to see which

side effects might affect you. Find the part of your body being

treated in the column on the left, then read across the row to

see the side effects. A checkmark means that you may get this

side effect. Ask your doctor or nurse about your chances of

getting each side effect.

|

Talk to your radiation therapy team about your

chances of getting side effects. Show them the

chart below.

|

- Find the part of your body being treated in the top row.

- Read down the column.

- A checkmark means you may get the side effect listed.

Radiation Therapy Side Effects and Ways to Manage Them

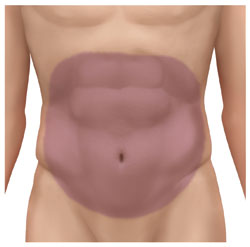

Radiation to the shaded area may

cause diarrhea.

|

What it is

Diarrhea is frequent bowel movements which may be soft,

formed, loose, or watery. Diarrhea can occur at any time

during radiation therapy.

Why it occurs

Radiation therapy to the pelvis, stomach, and abdomen

can cause diarrhea. People get diarrhea because radiation

harms the healthy cells in the large and small bowels.

These areas are very sensitive to the amount of radiation

needed to treat cancer.

Ways to manage

When you have diarrhea:

- Drink 8 to 12 cups of clear liquid per day. See

"Clear Liquids" 28

for ideas of drinks and foods

that are clear liquids.

If you drink liquids that are high in sugar (such as fruit juice, sweet iced tea,

Kool-Aid®, or Hi-C®) ask your nurse or dietitian if you should mix them with water.

- Eat many small meals and snacks. For instance, eat 5 or 6 small meals and snacks

rather than 3 large meals.

- Eat foods that are easy on the stomach (which means foods that are low in fiber, fat,

and lactose). See

"Foods and Drinks That Are Easy on the Stomach" 29

for other ideas of foods that are easy on the stomach. If your

diarrhea is severe, your doctor or nurse may suggest the BRAT diet, which stands for

bananas, rice, applesauce, and toast.

-

Take care of your rectal area. Instead of toilet paper, use a baby

wipe or squirt of water from a spray bottle to clean yourself after

bowel movements. Also, ask your nurse about taking

sitz baths 30,

which is a warm-water bath taken in a sitting position that covers

only the hips and buttocks. Be sure to tell your doctor or nurse if

your rectal area gets sore.

Take care of your rectal area. Instead of toilet paper, use a baby

wipe or squirt of water from a spray bottle to clean yourself after

bowel movements. Also, ask your nurse about taking

sitz baths 30,

which is a warm-water bath taken in a sitting position that covers

only the hips and buttocks. Be sure to tell your doctor or nurse if

your rectal area gets sore.

- Stay away from:

- Milk and dairy foods, such as ice cream, sour cream, and cheese

- Spicy foods, such as hot sauce, salsa, chili, and curry dishes

- Foods or drinks with caffeine, such as regular coffee, black tea, soda, and chocolate

- Foods or drinks that cause gas, such as cooked dried beans, cabbage, broccoli, soy milk, and other soy products

- Foods that are high in fiber, such as raw fruits and vegetables, cooked dried beans, and whole wheat breads and cereals

- Fried or greasy foods

- Food from fast food restaurants

- Talk to your doctor or nurse. Tell them if you are having diarrhea. He or she

will suggest ways to manage it. He or she may also suggest taking medicine, such

as Imodium®.

To learn more about dealing with diarrhea during cancer treatment, see

Eating Hints 13, a book

from the National Cancer Institute. You can get a free copy at www.cancer.gov/publications

or 1-800-4-CANCER.

|

Fatigue is a common

side effect, and there

is a good chance that

you will feel some

level of fatigue from

radiation therapy.

|

What it is

Fatigue from radiation therapy can range from a mild to

an extreme feeling of being tired. Many people describe

fatigue as feeling weak, weary, worn out, heavy, or slow.

Why it occurs

Fatigue can happen for many reasons. These include:

Fatigue can happen for many reasons. These include:

- Anemia

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Infection

- Lack of activity

- Medicines

Fatigue can also come from the effort of going to radiation therapy each day or from

stress. Most of the time, you will not know why you feel fatigue.

How long it lasts

When you first feel fatigue depends on a few factors, which include your age, health, level

of activity, and how you felt before radiation therapy started.

Fatigue can last from 6 weeks to 12 months after your last radiation therapy session. Some

people may always feel fatigue and, even after radiation therapy is over, will not have as

much energy as they did before.

Ways to manage

-

Try to sleep at least 8 hours each night. This may be more sleep

than you needed before radiation therapy. One way to sleep better

at night is to be active during the day. For example, you could go

for walks, do yoga, or ride a bike. Another way to sleep better at

night is to relax before going to bed. You might read a book, work

on a jigsaw puzzle, listen to music, or do other calming hobbies.

Try to sleep at least 8 hours each night. This may be more sleep

than you needed before radiation therapy. One way to sleep better

at night is to be active during the day. For example, you could go

for walks, do yoga, or ride a bike. Another way to sleep better at

night is to relax before going to bed. You might read a book, work

on a jigsaw puzzle, listen to music, or do other calming hobbies.

-

Plan time to rest. You may need to nap during the day. Many people say that it helps to

rest for just 10 to 15 minutes. If you do nap, try to sleep for less than 1 hour at a time.

-

Try not to do too much. With fatigue, you may not have enough energy to do all the

things you want to do. Stay active, but choose the activities that are most important to

you. For example, you might go to work but not do housework, or watch your

children's sports events but not go out to dinner.

- Exercise. Most people feel better when they get some exercise each day. Go for a

15- to 30-minute walk or do stretches or yoga. Talk with your doctor or nurse about

how much exercise you can do while having radiation therapy.

- Plan a work schedule that is right for you. Fatigue may affect the amount of energy

you have for your job. You may feel well enough to work your full schedule, or you

may need to work less - maybe just a few hours a day or a few days each week. You

may want to talk with your boss about ways to work from home so you do not have to

commute. And you may want to think about going on medical leave while you have

radiation therapy.

- Plan a radiation therapy schedule that makes sense for you. You may want to schedule

your radiation therapy around your work or family schedule. For example, you might

want to have radiation therapy in the morning so you can go to work in the afternoon.

- Let others help you at home. Check with your insurance company to see whether it

covers home care services. You can also ask family members and friends to help when

you feel fatigue. Home care staff, family members, and friends can assist with

household chores, running errands, or driving you to and from radiation therapy

visits. They might also help by cooking meals for you to eat now or freeze for later.

- Learn from others who have cancer. People who have cancer can help each other by

sharing ways to manage fatigue. One way to meet other people with cancer is by

joining a support group - either in person or online. Talk with your doctor or nurse to

learn more about support groups.

- Talk with your doctor or nurse. If you have trouble dealing with fatigue, your doctor

may prescribe medicine (called psychostimulants 31) that can help decrease fatigue, give

you a sense of well-being, and increase your appetite. Your doctor may also suggest

treatments if you have anemia, depression, or are not able to sleep at night.

What it is

Hair loss (also called alopecia) is when some or all of your hair falls out.

Why it occurs

Radiation therapy can cause hair loss because it damages cells that grow quickly, such as

those in your hair roots.

Hair loss from radiation therapy only happens on the part of your body being treated.

This is not the same as hair loss from chemotherapy, which happens all over your body.

For instance, you may lose some or all of the hair on your head when you get radiation to

your brain. But if you get radiation to your hip, you may lose pubic hair (between your

legs) but not the hair on your head.

How long it lasts

You may start losing hair in your treatment area 2 to 3 weeks after your first radiation

therapy session. It takes about a week for all the hair in your treatment area to fall out.

Your hair may grow back 3 to 6 months after treatment is over. Sometimes, though, the

dose of radiation is so high that your hair never grows back.

Once your hair starts to grow back, it may not look or feel the way it did before. Your hair

may be thinner, or curly instead of straight. Or it may be darker or lighter in color than it

was before.

Ways to manage hair loss on your head

Before hair loss:

- Decide whether to cut your hair or shave your head. You may feel more in control of

hair loss when you plan ahead. Use an electric razor to prevent nicking yourself if you

decide to shave your head.

If you plan to buy a wig, do so while you still have

hair. The best time to select your wig is before

radiation therapy begins or soon after it starts. This

way, the wig will match the color and style of your own

hair. Some people take their wig to their hair stylist.

You will want to have your wig fitted once you have lost

your hair. Make sure to choose a wig that feels

comfortable and does not hurt your scalp.

If you plan to buy a wig, do so while you still have

hair. The best time to select your wig is before

radiation therapy begins or soon after it starts. This

way, the wig will match the color and style of your own

hair. Some people take their wig to their hair stylist.

You will want to have your wig fitted once you have lost

your hair. Make sure to choose a wig that feels

comfortable and does not hurt your scalp.

- Check with your health insurance company to see whether it will pay for your wig.

If it does not, you can deduct the cost of your wig as a medical expense on your

income taxes. Some groups also sponsor free wig banks. Ask your doctor, nurse, or

social worker if he or she can refer you to a free wig bank in your area.

- Be gentle when you wash your hair. Use a mild shampoo, such as a baby shampoo.

Dry your hair by patting (not rubbing) it with a soft towel.

- Do not use curling irons, electric hair dryers, curlers, hair bands, clips, or hair sprays.

These can hurt your scalp or cause early hair loss.

- Do not use products that are harsh on your hair. These include hair colors, perms, gels,

mousse, oil, grease, or pomade.

After hair loss:

-

Protect your scalp. Your scalp may feel tender after hair loss.

Cover your head with a hat, turban, or scarf when you are outside.

Try not to be in places where the temperature is very cold or very

hot. This means staying away from the direct sun, sun lamps, and

very cold air.

Protect your scalp. Your scalp may feel tender after hair loss.

Cover your head with a hat, turban, or scarf when you are outside.

Try not to be in places where the temperature is very cold or very

hot. This means staying away from the direct sun, sun lamps, and

very cold air.

- Stay warm. Your hair helps keep you warm, so you may feel colder once you lose it.

You can stay warmer by wearing a hat, turban, scarf, or wig.

|

You will lose hair only on

the part of your body

being treated.

|

Radiation to the shaded area may cause mouth changes.

|

What they are

Radiation therapy to the head or neck can cause problems such as:

- Mouth sores (little cuts or ulcers in your mouth)

- Dry mouth (also called xerostomia) and throat

- Loss of taste

- Tooth decay

- Changes in taste (such as a metallic taste when you eat meat)

- Infections of your gums, teeth, or tongue

- Jaw stiffness and bone changes

- Thick, rope-like saliva

Why they occur

Radiation therapy kills cancer cells and can also damage healthy cells such as those in the

glands that make saliva and the soft, moist lining of your mouth.

How long they last

Some problems, like mouth sores, may go away after treatment ends. Others, such as taste

changes, may last for months or even years. Some problems, like dry mouth, may never

go away.

|

Visit a dentist at least

2 weeks before starting radiation

therapy to your head or neck.

|

Ways to manage

-

If you are getting radiation therapy to your head or neck, visit a dentist at least 2

weeks before treatment starts. At this time, your dentist will examine your teeth and

mouth and do any needed dental work to make sure your mouth

is as healthy as possible before radiation therapy. If you cannot

get to the dentist before treatment starts, ask your doctor if you

should schedule a visit soon after treatment begins.

If you are getting radiation therapy to your head or neck, visit a dentist at least 2

weeks before treatment starts. At this time, your dentist will examine your teeth and

mouth and do any needed dental work to make sure your mouth

is as healthy as possible before radiation therapy. If you cannot

get to the dentist before treatment starts, ask your doctor if you

should schedule a visit soon after treatment begins.

-

Check your mouth every day. This way, you can see or feel

problems as soon as they start. Problems can include mouth

sores, white patches, or infection.

- Keep your mouth moist. You can do this by:

- Sipping water often during the day

- Sucking on ice chips

- Chewing sugar-free gum or sucking on sugar-free hard candy

- Using a saliva substitute to help moisten your mouth

- Asking your doctor to prescribe medicine that helps

increase saliva

- Clean your mouth, teeth, gums, and tongue.

- Brush your teeth, gums, and tongue after every meal and

at bedtime.

- Use an extra-soft toothbrush. You can make the bristles

softer by running warm water over them just before

you brush.

- Use a fluoride toothpaste.

- Use a special fluoride gel that your dentist can prescribe.

- Do not use mouthwashes that contain alcohol.

- Gently floss your teeth every day. If your gums bleed or

hurt, avoid those areas but floss your other teeth.

- Rinse your mouth every 1 to 2 hours with a solution of

1/4 teaspoon baking soda and 1/8 teaspoon salt mixed in

1 cup of warm water.

- If you have dentures, make sure they fit well and limit how

long you wear them each day. If you lose weight, your

dentist may need to adjust them.

- Keep your dentures clean by soaking or brushing them

each day.

- Be careful what you eat when your mouth is sore.

- Choose foods that are easy to chew and swallow.

- Take small bites, chew slowly, and sip liquids with your meals.

- Eat moist, soft foods such as cooked cereals, mashed potatoes, and scrambled eggs.

- Wet and soften food with gravy, sauce, broth, yogurt, or other liquids.

- Eat foods that are warm or at room temperature.

- Stay away from things that can hurt, scrape, or burn your mouth, such as:

- Sharp, crunchy foods such as potato or corn chips

- Hot foods

- Spicy foods such as hot sauce, curry dishes, salsa, and chili

- Fruits and juices that are high in acid such as tomatoes, oranges, lemons,

and grapefruits

- Toothpicks or other

sharp objects

- All tobacco products,

including cigarettes, pipes,

cigars, and chewing tobacco

- Drinks that contain alcohol

- Stay away from foods and drinks that are high in sugar. Foods and drinks that have a

lot sugar (such as regular soda, gum, and candy) can cause tooth decay.

-

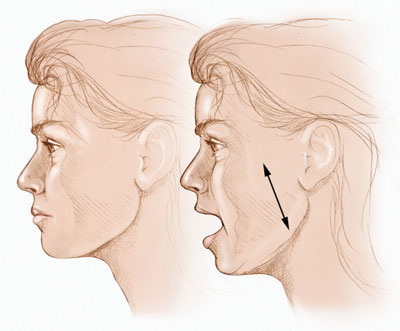

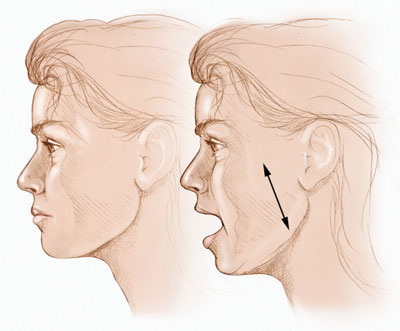

Exercise your jaw 3 times a day.

|

Exercise your jaw muscles.

Open and close your mouth 20 times as

far as you can without causing pain. Do

this exercise 3 times a day, even if your

jaw isn't stiff.

- Medicine. Ask your doctor or nurse about medicines that can protect your saliva

glands and the moist tissues that line your mouth.

- Call your doctor or nurse when your mouth hurts. There are medicines and other

products, such as mouth gels, that can help control mouth pain.

- You will need to take extra good care of your mouth for the rest of your life. Ask your

dentist how often you will need dental check-ups and how best to take care of your

teeth and mouth after radiation therapy is over.

|

Do not use tobacco or drink alcohol

while you are getting radiation therapy

to your head or neck.

|

Radiation to the shaded area may cause nausea and vomiting.

|

What they are

Radiation therapy can cause nausea, vomiting, or both.

Nausea is when you feel sick to your stomach and feel like

you are going to throw up. Vomiting is when you throw

up food and fluids. You may also have

dry heaves 32, which

happen when your body tries to vomit even though your

stomach is empty.

Why they occur

Nausea and vomiting can occur after radiation therapy to

the stomach, small intestine, colon, or parts of the brain.

Your risk for nausea and vomiting depends on how much

radiation you are getting, how much of your body is in

the treatment area, and whether you are also having

chemotherapy.

How long they last

Nausea and vomiting may occur 30 minutes to many hours after your radiation therapy

session ends. You are likely to feel better on days that you do not have radiation therapy.

Ways to manage

- Prevent nausea. The best way to keep from vomiting is to prevent nausea. One way to

do this is by having bland, easy-to-digest foods and drinks that do not upset your

stomach. These include toast, gelatin, and apple juice. To learn more, see the list of

Foods and Drinks That Are Easy on the Stomach 29.

-

Try to relax before treatment. You may feel less nausea if you

relax before each radiation therapy treatment. You can do

this by spending time doing activities you enjoy, such as

reading a book, listening to music, or other hobbies.

Try to relax before treatment. You may feel less nausea if you

relax before each radiation therapy treatment. You can do

this by spending time doing activities you enjoy, such as

reading a book, listening to music, or other hobbies.

- Plan when to eat and drink. Some people feel better when they eat before radiation

therapy; others do not. Learn the best time for you to eat and drink. For example, you

might want a snack of crackers and apple juice 1 to 2 hours before radiation therapy.

Or, you might feel better if you have treatment on an empty stomach, which means not

eating 2 to 3 hours before treatment.

- Eat small meals and snacks. Instead of eating 3

large meals each day, you may want to eat 5 or 6

small meals and snacks. Make sure to eat slowly

and do not rush.

- Have foods and drinks that are warm or cool

(not hot or cold). Before eating or drinking, let hot food and drinks cool down and

cold food and drinks warm up.

-

Talk with your doctor or nurse. He or she may suggest a

special diet of foods to eat or prescribe medicine to help

prevent nausea, which you can take 1 hour before each

radiation therapy session. You might also ask your doctor

or nurse about acupuncture, which may help relieve nausea

and vomiting caused by cancer treatment.

Talk with your doctor or nurse. He or she may suggest a

special diet of foods to eat or prescribe medicine to help

prevent nausea, which you can take 1 hour before each

radiation therapy session. You might also ask your doctor

or nurse about acupuncture, which may help relieve nausea

and vomiting caused by cancer treatment.

|

Eat 5 or 6 small meals and

snacks each day instead

of 3 large meals.

|

|

Learn more from Eating Hints 13, a book from the

National Cancer Institute.

To get a free copy,

contact the Cancer

Information Service.

|

What they are

Radiation therapy sometimes causes sexual changes, which can include hormone changes

and loss of interest in or ability to have sex. It can also affect fertility during and after

radiation therapy. For a woman, this means that she might not be able to get pregnant and

have a baby. For a man, this means that he might not be able to get a woman pregnant.

Sexual and fertility changes differ for men and women.

|

Be sure to tell your doctor if you are pregnant

before you start radiation therapy.

|

Problems for women include:

Radiation to the shaded area may cause sexual and fertility changes.

|

- Pain or discomfort when having sex

- Vaginal itching, burning, dryness, or atrophy (when

the muscles in the vagina become weak and the walls

of the vagina become thin)

- Vaginal stenosis 33, when the vagina becomes less elastic,

narrows, and gets shorter

- Symptoms of menopause for women not yet in

menopause. These include hot flashes, vaginal dryness,

and not having your period.

- Not being able to get pregnant after radiation therapy

is over

Problems for men include:

- Impotence (also called erectile dysfunction or ED),

which means not being able to have or keep an

erection

- Not being able to get a woman pregnant after radiation

therapy is over due to fewer or less effective sperm

Why they occur

Sexual and fertility changes can happen when people get radiation therapy to the pelvic

area. For women, this includes radiation to the vagina, uterus, or ovaries. For men, this

includes radiation to the testicles or prostate. Many sexual side effects are caused by scar

tissue from radiation therapy. Other problems, such as fatigue, pain, anxiety, or

depression, can affect your interest in having sex.

How long they last

After radiation therapy is over, most people want to have sex as much as they did before

treatment. Many sexual side effects go away after treatment ends. But you may have

problems with hormone changes and fertility for the rest of your life. If you are able to get

pregnant or father a child after you have finished radiation therapy, it should not affect the

health of the baby.

Ways to manage

For both men and women, it is important to be open and

honest with your spouse or partner about your feelings,

concerns, and how you prefer to be intimate while you are

getting radiation therapy.

For both men and women, it is important to be open and

honest with your spouse or partner about your feelings,

concerns, and how you prefer to be intimate while you are

getting radiation therapy.

For women, here are some issues to discuss with your doctor or nurse:

- Fertility. Before radiation therapy starts, let your doctor or nurse know if you think

you might want to get pregnant after your treatment ends. He or she can talk with you

about ways to preserve your fertility, such as preserving your eggs to use in the future.

- Sexual problems. You may or may not have sexual problems. Your doctor or nurse can

tell you about side effects you can expect and suggest ways for coping with them.

- Birth control. It is very important that you do not get pregnant while having radiation

therapy. Radiation therapy can hurt the fetus at all stages of pregnancy. If you have

not yet gone through menopause, talk with your doctor or nurse about birth control

and ways to keep from getting pregnant.

-

Pregnancy. Make sure to tell your doctor or nurse if you are already pregnant.

-

Stretching your vagina. Vaginal stenosis is a common problem for women who have

radiation therapy to the pelvis. This can make it painful to have sex. You can help by

stretching your vagina using a dilator (a device that gently stretches the tissues of the

vagina). Ask your doctor or nurse where to find a dilator and how to use it.

- Lubrication. Use a special lotion for your vagina (such as Replens®) once a day to keep

it moist. When you have sex, use a water- or mineral oil-based lubricant (such as K-Y

Jelly® or Astroglide®).

- Sex. Ask your doctor or nurse whether it is okay for you to have sex during radiation

therapy. Most women can have sex, but it is a good idea to ask and be sure. If sex is

painful due to vaginal dryness, you can use a water- or mineral oil-based lubricant.

|

Talk to your doctor or nurse

if you want to have

children in the future.

|

For men, here are some issues to discuss with your doctor or nurse:

- Fertility. Before you start radiation therapy, let your doctor or nurse know if you think

you might want to father children in the future. He or she may talk with you about

ways to preserve your fertility before treatment starts, such as banking your sperm.

Your sperm will need to be collected before you begin radiation therapy.

- Impotence. Your doctor or nurse can let you know whether you are likely to become

impotent and how long it might last. Your doctor can prescribe medicine or other

treatments that may help.

- Sex. Ask if it is okay for you to have sex during radiation therapy. Most men can have

sex, but it is a good idea to ask and be sure.

|

If you want to father children in the future,

your sperm will need to be collected before

you begin treatment.

|

What they are

Radiation therapy can cause skin changes in your treatment area. Here are some common

skin changes:

- Redness. Your skin in the treatment area may look as if you have a mild to severe

sunburn or tan. This can occur on any part of your body where you are getting

radiation.

- Pruritus 34. The skin in your treatment area may itch so much that you always feel like

scratching. This causes problems because scratching too much can lead to skin

breakdown 35 and infection.

- Dry and peeling skin. This is when the skin in your treatment area gets very dry -

much drier than normal. In fact, your skin may be so dry that it peels like it does after

a sunburn.

- Moist reaction. Radiation kills skin cells in your treatment area, causing your skin to

peel off faster than it can grow back. When this happens, you can get sores or ulcers.

The skin in your treatment area can also become wet, sore, or infected. This is more

common where you have skin folds, such as your buttocks, behind your ears, under

your breasts. It may also occur where your skin is very thin, such as your neck.

- Swollen skin. The skin in your treatment area may be swollen and puffy.

Why they occur

Radiation therapy causes skin cells to break down and die. When people get radiation

almost every day, their skin cells do not have enough time to grow back between

treatments. Skin changes can happen on any part of the body that gets radiation.

How long they last

Skin changes may start a few weeks after you begin radiation therapy. Many of these

changes often go away a few weeks after treatment is over. But even after radiation therapy

ends, you may still have skin changes. Your treated skin may always

look darker and blotchy. It may feel very dry or thicker than before.

And you may always burn quickly and be sensitive to the sun. You will

always be at risk for skin cancer in the treatment area. Be sure to avoid

tanning beds and protect yourself from the sun by wearing a hat, long

sleeves, long pants, and sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or higher.

Skin changes may start a few weeks after you begin radiation therapy. Many of these

changes often go away a few weeks after treatment is over. But even after radiation therapy

ends, you may still have skin changes. Your treated skin may always

look darker and blotchy. It may feel very dry or thicker than before.

And you may always burn quickly and be sensitive to the sun. You will

always be at risk for skin cancer in the treatment area. Be sure to avoid

tanning beds and protect yourself from the sun by wearing a hat, long

sleeves, long pants, and sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or higher.

Ways to manage

- Skin care. Take extra good care of your

skin during radiation therapy. Be gentle

and do not rub, scrub, or scratch in the

treatment area. Also, use creams that your

doctor prescribes.

|

Take extra good care of your

skin during radiation therapy.

Be gentle and do not rub,

scrub, or scratch.

|

- Do not put anything on your skin that is

very hot or cold. This means not using heating pads, ice packs, or other hot or cold

items on the treatment area. It also means washing with lukewarm water.

- Be gentle when you shower or take a bath. You can take a lukewarm shower every

day. If you prefer to take a lukewarm bath, do so only every other day and soak for less

than 30 minutes. Whether you take a

shower or bath, make sure to use a mild

soap that does not have fragrance or

deodorant in it. Dry yourself with a soft

towel by patting, not rubbing, your skin.

Be careful not to wash off the ink markings

that you need for radiation therapy.

|

Be careful not to wash off the

ink markings you need for

radiation therapy.

|

-

Use only those lotions and skin products that your doctor or nurse suggests. If you

are using a prescribed cream for a skin problem or acne, you must tell your doctor or

nurse before you begin radiation treatment. Check with your doctor or nurse before

using any of the following skin products:

- Bubble bath

- Cornstarch

- Cream

- Deodorant

- Hair removers

- Makeup

|

|

- Oil

- Ointment

- Perfume

- Powder

- Soap

- Sunscreen

|

If you use any skin products on days you have radiation therapy, use them at least

4 hours before your treatment session.

- Cool, humid places. Your skin may feel much better when you are in cool, humid

places. You can make rooms more humid by putting a bowl of water on the radiator or

using a humidifier. If you use a humidifier, be sure to follow the directions about

cleaning it to prevent bacteria.

- Soft fabrics. Wear clothes and use bed sheets that are soft, such as those made

from cotton.

- Do not wear clothes that are tight and do not breathe, such as girdles and pantyhose.

-

Protect your skin from the sun every day. The sun can burn you even on cloudy days

or when you are outside for just a few minutes. Do not go to the

beach or sun bathe. Wear a broad-brimmed hat, long-sleeved shirt,

and long pants when you are outside. Talk with your doctor or nurse

about sunscreen lotions. He or she may suggest that you use a

sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or higher. You will need to protect your

skin from the sun even after radiation therapy is over, since you will

have an increased risk of skin cancer for the rest of your life.

Protect your skin from the sun every day. The sun can burn you even on cloudy days

or when you are outside for just a few minutes. Do not go to the

beach or sun bathe. Wear a broad-brimmed hat, long-sleeved shirt,

and long pants when you are outside. Talk with your doctor or nurse

about sunscreen lotions. He or she may suggest that you use a

sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or higher. You will need to protect your

skin from the sun even after radiation therapy is over, since you will

have an increased risk of skin cancer for the rest of your life.

- Do not use tanning beds. Tanning beds expose you to the same harmful effects as

the sun.

- Adhesive tape. Do not put bandages, BAND-AIDS®, or other types of sticky tape on

your skin in the treatment area. Talk with your doctor or nurse about ways to bandage

without tape.

- Shaving. Ask your doctor or nurse if you can shave the treated area. If you can shave,

use an electric razor and do not use pre-shave lotion.

-

Rectal area. If you have radiation therapy to the rectal area, you

are likely to have skin problems. These problems are often worse

after a bowel movement. Clean yourself with a baby wipe or

squirt of water from a spray bottle. Also ask your nurse about sitz

baths (a warm-water bath taken in a sitting position that covers

only the hips and buttocks.)

Rectal area. If you have radiation therapy to the rectal area, you

are likely to have skin problems. These problems are often worse

after a bowel movement. Clean yourself with a baby wipe or

squirt of water from a spray bottle. Also ask your nurse about sitz

baths (a warm-water bath taken in a sitting position that covers

only the hips and buttocks.)

-

Talk with your doctor or nurse. Some skin changes can be very

serious. Your treatment team will check for skin changes

each time you have radiation therapy. Make sure to report

any skin changes that you notice.

Medicine. Medicines can help with some skin changes.

They include lotions for dry or itchy skin, antibiotics to treat

infection, and other drugs to reduce swelling or itching.

Medicine. Medicines can help with some skin changes.

They include lotions for dry or itchy skin, antibiotics to treat

infection, and other drugs to reduce swelling or itching.

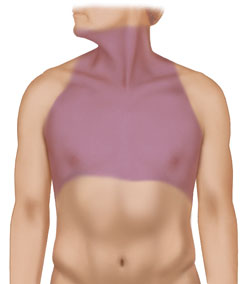

Radiation to the shaded area may cause throat changes.

|

What they are

Radiation therapy to the neck or chest can cause the lining of

your throat to become inflamed and sore. This is called

esophagitis. You may feel as if you have a lump in your

throat or burning in your chest or throat. You may also have

trouble swallowing.

Why they occur

Radiation therapy to the neck or chest can cause throat changes because it not only kills cancer

cells, but can also damage the healthy cells that line your throat. Your risk for throat changes

depends on how much radiation you are getting, whether you are also having chemotherapy,

and whether you use tobacco and alcohol while you are getting radiation therapy.

How long they last

You may notice throat changes 2 to 3 weeks after starting radiation. You will most likely

feel better 4 to 6 weeks after radiation therapy has finished.

Ways to manage

- Be careful what you eat when your throat is sore.

- Choose foods that are easy to swallow.

- Cut, blend, or shred foods to make them easier to eat.

- Eat moist, soft foods such as cooked cereals, mashed potatoes, and scrambled eggs.

- Wet and soften food with gravy, sauce, broth, yogurt, or other liquids.

- Drink cool drinks.

- Sip drinks through a straw.

- Eat foods that are cool or at room temperature.

- Eat small meals and snacks. It may be easier to eat a small amount of food at one

time. Instead of eating 3 large meals each day, you may want to eat 5 or 6 small meals

and snacks.

- Choose foods and drinks that are high in calories and protein. When it hurts to

swallow, you may eat less and lose weight. It is important to keep your weight the

same during radiation therapy. Having foods and drinks that are high in calories and

protein can help you. See the

chart of foods and drinks that are high in calories and

protein 12 for ideas.

- Sit upright and bend your head slightly forward when you are eating or drinking.

Remain sitting or standing upright for at least 30 minutes after eating.

- Don't have things that can burn or scrape your throat, such as:

- Hot foods and drinks

- Spicy foods

- Foods and juices that are high in acid, such as tomatoes and oranges

- Sharp, crunchy foods such as potato or corn chips

- All tobacco products, such as cigarettes, pipes, cigars, and chewing tobacco

- Drinks that contain alcohol

- Talk with a dietitian. He or she can help make sure you eat enough to maintain your

weight. This may include choosing foods that are high in calories and protein and

foods that are easy to swallow.

- Talk with your doctor or nurse.

Let your doctor or nurse know if you

notice throat changes, such as trouble

swallowing, feeling as if you are choking,

or coughing while eating or drinking.

Also, let him or her know if you have

pain or lose any weight. Your doctor can

prescribe medicines that may help relieve

your symptoms, such as antacids, gels that

coat your throat, and pain killers.

Let your doctor or nurse know

if you:

- Have trouble swallowing

- Feel as if you are choking

- Cough while you are eatingor drinking

|

Radiation to the shaded area may cause urinary and bladder changes.

|

What they are

Radiation therapy can cause urinary and bladder problems,

which can include:

- Burning or pain when you begin to urinate 36 or after you empty your bladder

- Trouble starting to urinate

- Trouble emptying your bladder

- Frequent, urgent need to urinate

- Cystitis 37, a swelling (inflammation) in your urinary tract

- Incontinence, when you cannot control the flow of urine from your bladder, especially when coughing or sneezing

- Frequent need to get up during sleep to urinate

- Blood in your urine

- Bladder spasms, which are like painful muscle cramps

Why they occur

Urinary and bladder problems may occur when people get radiation therapy to the

prostate or bladder. Radiation therapy can harm the healthy cells of the bladder wall and

urinary tract, which can cause inflammation, ulcers, and infection.

How long they last

Urinary and bladder problems often start 3 to 5 weeks after radiation therapy begins.

Most problems go away 2 to 8 weeks after treatment is over.

Ways to manage

- Drink a lot of fluids. This means 6 to 8 cups of fluids each

day. Drink enough fluids so that your urine is clear to light

yellow in color.

-

Avoid coffee, black tea, alcohol, spices, and all

tobacco products.

Avoid coffee, black tea, alcohol, spices, and all

tobacco products.

-

Talk with your doctor or nurse if you think you have

urinary or bladder problems. He or she may ask for a

urine sample to make sure that you do not have an

infection.

-

Talk to your doctor or nurse if you have incontinence.

He or she may refer you to a physical therapist who will

assess your problem. The therapist can give you exercises

to improve bladder control.

Talk to your doctor or nurse if you have incontinence.

He or she may refer you to a physical therapist who will

assess your problem. The therapist can give you exercises

to improve bladder control.

-

Medicine. Your doctor may prescribe antibiotics if your problems are caused by an

infection. Other medicines can help you urinate, reduce burning or pain, and ease

bladder spasms.

|

Drink 6 to 8 cups

of fluids each day.

|

Late Radiation Therapy Side Effects

Late side effects are those that first occur at least 6 months after radiation therapy is over.

Late side effects are rare, but they do happen. It is important to have follow-up care with

a radiation oncologist or nurse practitioner for the rest of your life.

Whether you get late side effects will depend on:

- The part of your body that was treated

- The dose and length of your radiation therapy

- If you received chemotherapy before, during, or after radiation therapy

Your doctor or nurse will talk with you about late side effects and discuss ways to help

prevent them, symptoms to look for, and how to treat them if they occur.

Some late side effects are brain problems, infertility, joint problems, lymphedema, mouth

problems, and secondary cancers.

What they are

Radiation therapy to the brain can cause problems months or years after treatment ends.

Side effects can include memory loss, problems doing math, movement problems,

incontinence, trouble thinking, or personality changes. Sometimes, dead tumor cells can

form a mass in the brain, which is called radiation necrosis.

Ways to manage

You will need to have check-ups with your doctor or nurse for the rest of your life. If you

have symptoms, you will have tests to see whether they are due to the cancer or late side

effects.