Testimony Statement by

Kerry Weems,

Acting Administrator

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

on

In the Hands of Strangers: Are Nursing Home Safeguards Working before

House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations

Thursday, May 15, 2008

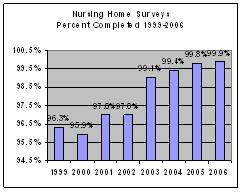

Good afternoon Chairman Stupak, Representative Whitfield and distinguished members of Congress. It is my pleasure to be here today to discuss the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) initiatives undertaken in the past few years to improve the quality of care for nursing home residents. Our quality efforts in this area are broad, including initiatives to enhance consumer awareness and transparency, as well as rigorous survey and enforcement processes to ensure nursing facilities provide quality care to their residents. Background Americans are growing older and living longer – many with complex, chronic medical conditions. As increasing numbers of our nation’s baby boom generation retire, the need for high-quality long term care, both in the community and in nursing homes will grow commensurately. About 1.5 million Americans reside in the nation’s 16,000 nursing homes on any given day.1 More than 3 million Americans rely on services provided by a nursing home at some point during the year.2 Those individuals, and an even larger number of their family members, friends, and relatives, must be able to count on nursing homes to provide reliable care of consistently high quality. In 2006, 7.4 percent (2.8 million) of the 37.3 million persons aged 65 and over in the United States stayed at a nursing home.3 By contrast, 22 percent of the 5.3 million persons aged 85 and older stayed at a nursing home in 2006. Some of these were long-term nursing home residents, while some had shorter stays for skilled nursing care following an acute hospitalization.4 Roughly 1.8 million persons received Medicare-covered care in skilled nursing facilities in 2005.5 Medicare skilled nursing facility benefit payments increased from $17.6 billion in 2005 to nearly $21.0 billion in Fiscal Year (FY) 2007.6 Approximately 1.7 million persons received Medicaid-covered care in nursing facilities during 2004.7 Medical assistance payments for Medicaid-covered nursing facility services topped $47 billion in FY 2005, representing nearly 16 percent of overall medical assistance payments that year.8 Action Plan for Nursing Home Quality Congress has authorized a variety of tools that enable CMS to promote – in the words of the statute – “…the highest practicable physical, mental, and psychosocial well-being of each resident…” 9 The most effective approach to ensure quality is one that mobilizes all available tools and aligns them in a comprehensive strategy. An internal CMS Long Term Care Task Force helps shape and guide the Agency’s comprehensive strategy for nursing home quality. Each year, CMS publishes a comprehensive Nursing Home Action Plan10 on our web site, which reflects the vision and priorities of the Task Force and the Agency. The current Action Plan outlines five inter-related and coordinated approaches – or principles of action – for nursing home quality, as described in detail below. Consumer Awareness and Assistance. The first principle of action is consumer awareness and assistance. Aged individuals, people who have a disability, their families, friends, and neighbors are all essential participants in achieving high quality care in any health care system. The availability of relevant, timely information can significantly help such individuals to be active, informed participants in their care. This information also can increase the ability of such individuals to hold the health care system accountable for the quality of services and support that should be provided. To that end, CMS seeks to provide an increasing array of understandable information that can be readily accessed by the public. With regard to nursing home care specifically, the CMS web site “Nursing Home Compare” at www.Medicare.gov features key information on each nursing home; the results of their three most recent quality of care inspections; and other important information for consumers, families, and friends. The web site contains the results of 19 different quality of care measures for each nursing home, such as the percent of residents who have pressure ulcers or are subject to physical restraints. Recently, CMS added information about the extent fire-safety features in each nursing home and any deficiencies. CMS also added information about the percent of residents who were vaccinated for flu and pneumonia. Survey, Standards, and Enforcement Processes. The second principle is to have clear expectations for quality of care that are properly enforced. CMS establishes both quality of care and safety requirements for providers and suppliers that participate in the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Such requirements are carefully crafted to highlight key areas of quality and convey basic, enforceable expectations that nursing homes must meet. Consistent with statutory requirements, more than 4,000 Federal and State surveyors conduct on-site reviews of every nursing home at least once every 15 months (and about once a year on average). CMS also contracts with quality improvement organizations (QIOs) to assist nursing homes to make vital improvements in an increasingly large number of priority areas. In August of this year, a new CMS contract for the QIOs will take effect. CMS plans to build into that contract an ambitious, 3-year agenda for the QIOs to work with nursing homes that have poor quality, including the Special Focus Facilities (SFFs).  We take our responsibilities for on-site surveys of nursing homes seriously. In 2006, the most recent year for which complete data are available, the percent of nursing homes that were surveyed at least every fifteen months reached 99.9 percent – the highest rate ever recorded. In addition to about 16,000 comprehensive surveys that year, CMS and States conducted more than 45,000 complaint investigations in nursing homes. Our strengthened fire-safety inspections led to the identification of 67.8 percent more fire-safety deficiencies in 2006 compared to 2002 (to 66,470 from 39,618). Nursing homes have responded to these findings by improving their fire-safety capability. We take our responsibilities for on-site surveys of nursing homes seriously. In 2006, the most recent year for which complete data are available, the percent of nursing homes that were surveyed at least every fifteen months reached 99.9 percent – the highest rate ever recorded. In addition to about 16,000 comprehensive surveys that year, CMS and States conducted more than 45,000 complaint investigations in nursing homes. Our strengthened fire-safety inspections led to the identification of 67.8 percent more fire-safety deficiencies in 2006 compared to 2002 (to 66,470 from 39,618). Nursing homes have responded to these findings by improving their fire-safety capability.

Quality Improvement: The third Nursing Home Action Plan principle is to have effective quality improvement strategies. CMS is promoting a program of quality improvement in a number of key areas. These areas include reduction in the extent to which restraints are used in nursing homes; reduction in the prevalence of preventable pressure sores that threaten the health and well-being of a significant number of nursing home residents; and the Agency’s participation in a larger national movement known as “culture change.” Culture change principles echo Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1987 principles of knowing and respecting each nursing home resident in order to provide individualized care that best enhances each person’s quality of life. The concept of culture change encourages facilities to change outdated practices to allow residents more input into their own care and encourages staff to serve as a team that responds to what each person wants and needs. This past April, CMS co-sponsored a well-attended national symposium on culture change and we anticipate the recommendations that came out of the symposium will be available in the near future. Quality Through Partnerships: The fourth Nursing Home Action Plan principle is to promote quality through enthusiastic partnerships with any and all organizations that will join with us. No single approach or actor can fully assure quality. CMS must mobilize and coordinate many actors and many techniques through a partnership approach. State survey agencies and the QIOs under contract with CMS are more than ever coordinating their distinct roles so as to achieve better results than could be achieved by any one actor alone. CMS is also a founding member of the “Advancing Excellence in America’s Nursing Homes” campaign. This campaign is a collaboration among government agencies, advocacy organizations, nursing home associations, foundations, and many others to improve the quality of nursing homes across the country. 11 The campaign voluntarily enlists nursing homes to measure and make improvements in eight key quality of care areas. More than 6,000 nursing homes have signed up to make quality improvements such as the consistent assignment of staff to individual nursing home residents; the assessment of satisfaction on the part of residents and families; or the reduction of pressure ulcers. Value-Based Purchasing: The fifth principle of the Nursing Home Action Plan is to use purchasing power to promote quality. As the largest third-party purchasers of nursing home services in the country, States and CMS exert leverage to insist on certain levels of quality. CMS is working collaboratively with private and public organizations to stimulate high quality care and improve efficiency. Payment reforms could show promise in encouraging providers to deliver care that prevents complications, avoids unnecessary medical services, and achieves better outcomes at a lower overall cost. With these five principles in mind, the testimony will now turn to two topics that we understand may be of special interest to the Committee. The first is the issue of nursing home ownership, and the second is the CMS “Special Focus Facility” initiative. Nursing Home Ownership CMS is aware of recent media reports about the relationship between quality nursing home care and nursing home ownership, particularly investor-owned facilities. We understand the importance of responsible ownership of nursing facilities serving the Medicare and Medicaid population. CMS has developed a system called the Provider Enrollment Chain and Ownership System (PECOS). This electronic(?) system is designed to capture and maintain enrollment information submitted via the provider enrollment application, including information regarding entities that own five percent or more of a nursing home and to ensure only eligible providers and suppliers are enrolled and maintain enrollment in the Medicare program. Beyond the five percent ownership interest requirement, the PECOS system also reflects any entity that has managing control of the provider or partnership interest in the provider, regardless of the percentage of ownership the partner has. The primary function of the provider enrollment application is to gather information from a provider or supplier that tells CMS who it is; whether it meets State licensing qualifications and federal quality of care and safety requirements to participate in Medicare; where it practices or renders its services; the identity of the owner of the enrolling entity; and information necessary to establish the correct claim payment. The PECOS database currently has enrollment information on 70 percent of nursing homes enrolled in the Medicare program. Nursing homes are required to submit updates to their existing provider enrollment when they have a change in information, such as ownership, which then populates the PECOS database. Using PECOS, CMS has the ability to better track ownership and changes in ownership. CMS also is developing an Internet-based enrollment application which will allow all providers, including nursing homes, physicians and other suppliers to enroll or update their enrollment information via the Internet. We believe that the new approach will allow nursing homes to maintain up-to-date enrollment information. CMS focuses on the quality of care experienced by residents regardless of who owns the facility. Our focus on actual outcomes ensures that Medicare’s quality assurance system does not depend on any theory of quality or theory of ownership. Instead, the federal survey and certification system is grounded in what CMS and State nursing home surveyors actually find through on-site inspection; through in-person interviews with residents and staff; through the eyewitness observation of care processes; and through the review of records of care. CMS continuously seeks to improve the effectiveness of both the survey process and the enforcement of quality of care requirements. An example of such continuous improvement is our Special Focus Facility initiative that addresses the issue of nursing homes that persist in providing poor quality. Special Focus Facility Program The Special Focus Facility (SFF) program was initiated because a number of facilities consistently provided poor quality care, yet periodically fixed a sufficient number of the presenting problems to enable them to pass one survey, only to fail the next survey. Moreover, they often failed the next survey for many of the same problems as before. Such facilities with an “in and out” or “yo-yo” compliance history rarely addressed the underlying systemic problems that were giving rise to repeated cycles of serious deficiencies. Nursing homes on the Special Focus list represent those with the worst survey findings in the country, based on the most recent three years of survey history. The selection methodology takes into account the severity of deficiencies and the number of deficiencies. Deficiencies identified during complaint investigations are also included in the computation. Each State selects its Special Focus nursing homes from a CMS candidate list of approximately 15 eligible nursing homes in their own State, using additional information available to the State regarding the nursing homes’ quality of care in order to make the final selection. As of April 2008, there were 134 SFF-designated homes, out of about 16,000 active Medicare- or Medicaid-participating facilities. As homes improve their quality of care and “graduate” from the program, or fail to improve and are terminated from Medicare and Medicaid, new homes are added to the list. States conduct twice the number of standard surveys for Special Focus nursing homes compared to other nursing homes. If serious problems continue, then CMS applies progressive enforcement until the nursing home either (a) graduates from the Special Focus program because it makes significant improvements that last; (b) is terminated from participation in the Medicare and Medicaid programs; or (c) is given more time due to a trendline of improvement and promising developments, such as sale of the nursing home to a new owner with a better track record of providing quality care. To analyze the impact of the Special Focus Facility initiative, CMS compared the 128 nursing homes selected in 2005 with alternate nursing homes on the candidate list that were not selected. The Special Focus nursing homes had more deficiencies than others: 11 deficiencies on average in the Special Focus Facilities compared with 9 deficiencies for the alternates and 7 for nursing homes on average. However, over the course of the next two years approximately 42 percent of the Special Focus nursing homes had significantly improved to the point of meeting the Special Focus Facility graduation criteria, whereas only 29 percent of the alternates had equally improved. At the same time, change of ownership or closure of poorly performing nursing homes was greater in the Special Focus nursing homes. Approximately 15 percent of the Special Focus nursing homes were terminated from participation in Medicare compared with less than 8 percent in the alternates and 2 percent for all other nursing homes. The better response of the Special Focus nursing homes in addressing deficiencies has been a function of the greater attention that CMS paid to those nursing homes on the Special Focus Facility list, and the imperative for action that is built into the Special Focus Facility program design. The Special Focus initiative can pay great quality-of-care dividends for nursing home residents. For example, a nursing home in rural Monck’s Corner, South Carolina, was a Special Focus nursing home that failed to improve significantly over the 18 months after it was first selected. As a result, in April 2007 CMS issued a Medicare notice of termination to the facility. We were prepared to see the 132 nursing home residents relocated to other facilities that provided better care. At that point, however, the nursing home operators evidenced a willingness to implement the type of serious reforms that had clear potential to transform their quality of care. CMS agreed to extend the termination date provided the nursing home would enter into a legally-binding agreement to institute certain quality-focused reforms. We required that they undergo a root cause analysis of their underlying systems-of-care deficiencies, to be conducted by a QIO selected by CMS. We required that the nursing home then develop an action plan based on the root cause analysis, and also place $850,000 in escrow to pay for the reforms indicated by the action plan and root cause analysis. These interventions were successful. The nursing home passed the subsequent survey, was purchased by another owner, and is on track to graduate later this year from the Special Focus Facility initiative provided it can sustain the improvements over time. The corporation that operated the nursing home is now seeking to replicate this approach with other nursing homes that it operates. For the past several months, CMS has been working to bring added transparency to the SFF program. Increased consumer transparency on the initiative started in November 2007, when CMS began publishing on www.medicare.gov the list of SFF-designated nursing homes on the www.medicare.gov web site. In February 2008 we published an updated, expanded list of nursing homes in the SFF initiative, including further information on their specific designation (e.g., new addition, not improved, improving, recently graduated or no longer in the Medicare and Medicaid programs). Last month, we linked the posted SFF information to the Nursing Home Compare web site, with nursing home SFF designations now noted on Nursing Home Compare. We will continue to evaluate the impact and potentially build upon these efforts to promote increased consumer transparency. Conclusion Mr. Chairman, thank you for the opportunity to testify here today. Regardless of setting or ownership, quality health and long-term care for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries is of the utmost importance to CMS. To that end, I plan to work to ensure high quality medical care for all nursing home residents. I would be pleased to address any questions or hear any comments you may have. 1 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2008 Action Plan for (Further Improvement of) Nursing Home Quality (http://www.cms.hhs.gov/CertificationandComplianc/Downloads/2008NHActionPlan.pdf).

2 Ibid.

3 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Nursing Home Data Compendium (http://www.cms.hhs.gov/CertificationandComplianc/12_NHs.asp#TopOfPage).

4 Ibid.

5 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2007 CMS Statistics at 4 and 34. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

6 2007 CMS Statistics at 3 and 28.

7 2007 CMS Statistics at 4 and 39. “Nursing facility” in this context includes SNFs and all other nursing facilities other than intermediate care facilities (ICF/MR). 8 2007 CMS Statistics at 29. Note these figures exclude payments under SCHIP.

9 Section 1819(b)(2) of the Social Security Act.

10 See http://www.cms.hhs.gov/CertificationandComplianc/12_NHs.asp#TopOfPage

11 Information about the campaign for Advancing Excellence in America’s Nursing Homes may be found at: http://www.nhqualitycampaign.org

Last revised: August 29,2008 |