Statement on Alzheimer’s Disease to Senate Appropriations Committee, Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services and Education

Richard J. Hodes, M.D.

Director

National Institute on Aging

April 3, 2001

Mr. Chairman and Members of the Committee:

Thank you for inviting me to appear before you today on an issue of interest and concern to us all, Alzheimer’s disease. I am Dr. Richard Hodes, Director of the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the lead federal agency for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) research. It is an honor to return to the Subcommittee with promising news about the progress that has been made in the past year to understand, treat and prevent AD. The fast pace of research is providing insight into AD as well as other neurodegenerative diseases and normal brain function.

Preventing Alzheimer’s Disease: The AD Prevention Initiative

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia among older persons. It is a progressive, and at present irreversible, brain disorder that leads to a devastating decline in intellectual abilities and changes in behavior and personality. AD patients eventually become dependent on others for every aspect of their care. Scientists believe that AD develops as a result of a complex cascade of events, influenced by genetic and non-genetic factors, taking place over time inside the brain. These events cause the brain to develop lesions, including beta amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, and to lose nerve cells and the connections between them in a process that eventually interferes with normal brain function.

As many as four million Americans now suffer from Alzheimer’s disease.1 The prevalence of AD doubles every five years beyond the age of 65, which will lead to dramatic increases in the number of new cases as the population ages. The last Census Bureau projections indicated there will be approximately 20 million people in the United States aged 85 or older by 2050, suggesting that there will be many more people at very high risk for AD. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) recognizes the urgency of this public health threat and is committed to supporting critical bench-to-bedside research to develop strategies for treating and, more importantly, preventing the onset of this devastating disease.

The AD Prevention Initiative is a congressionally-supported intensive coordinated effort among several NIH Institutes, including the NIA, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), and National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), to accelerate basic research and the movement of basic research findings into clinical practice. Improved understanding of the initial stages of AD has allowed researchers to focus on the development and testing of new treatments targeted at the earliest stages of the disease process. The core goals of the initiative are to invigorate discovery and testing of new treatments, identify risk and protective factors, enhance methods of early detection and diagnosis, and advance basic science to understand AD. The initiative also endeavors to improve patient care strategies and to alleviate caregiver burden. (Chart #1)

Ongoing Clinical Trials

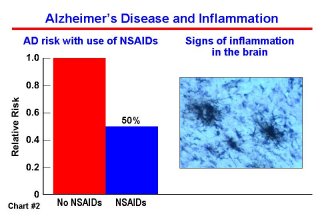

The NIA is currently supporting 17 AD clinical trials, seven of which are large-scale cognitive impairment and AD prevention trials. Prevention trials are among the most challenging and costly of research projects but, if successful, the payoff for people at risk, their relatives and society will be significant. Many of the agents being tested in these trials have been suggested as possible interventions based on long-term epidemiological and molecular studies. For example, epidemiology studies show that persons who have taken anti-inflammatory drugs have a lower risk of developing AD; and in basic research, inflammation around plaques is a hallmark of the disease. (Chart #2) There are similar rationales for estrogen and for anti-oxidant therapies. The first large-scale AD prevention clinical trial supported by the NIH, the Memory Impairment Study (MIS), is evaluating vitamin E and donepezil (Aricept) over a three-year period for their effectiveness in slowing or stopping the conversion from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to AD. MCI is a condition characterized by a major memory deficit without dementia. The trial is being conducted by the NIA-funded Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS) group at medical research institutions in North America, including NIA-supported Alzheimer’s Disease Centers. The trial is scheduled to end in 2003. Other recently-started primary prevention trials will be completed in the years from 2003 through 2008. These trials are testing a variety of agents, such as aspirin, antioxidants such as vitamin E, combined folate/B6/B12 supplementation, estrogen, anti-inflammatory drugs, and ginkgo biloba, to determine if they will slow the rate of cognitive decline or prevent AD onset. (Chart #3) As scientists await the outcome of these ongoing studies, the next generation of drugs is being developed, targeting specific pathways in plaque and tangle formation and dysfunction and death of brain cells.

Information about ongoing clinical trials and recruitment opportunities is available to the public through the NIA-supported Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center web site (www.alzheimers.nia.nih.gov) and toll-free number (1-800-438-4380), as well as on the NIH clinical trials web site (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

From Basic Science to Treatment

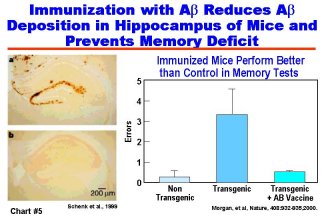

Developing effective treatments for AD based on advances in basic research is a major focus of NIA-supported studies. Important progress has been made in recent years by generating animal models of AD through genetic engineering of transgenic mice that express human AD genes and that express features of the human disease, such as the formation of amyloid plaques. In addition, the ability of researchers to develop drugs for effective treatment of AD was greatly enhanced last year by the discovery of enzymes called secretases. These enzymes are involved in the clipping of a normal cell surface protein to produce the amyloid peptide that forms the senile plaques found in the brains of AD patients. (Chart #4) The discovery of these enzymes, together with availability of animal models of AD, will be critical to the development and testing of effective and safe amyloid-preventing drugs. Major advances were also reported by researchers in the public and private sectors regarding the amyloid immunization approach to blocking the formation of amyloid plaques. In another major development, vaccine treatment prevented much of the cognitive decline usually seen with age in two AD transgenic mouse models. (Chart #5) To accelerate research into the vaccine approach to treating AD, NIA and NINDS have announced a Request for Applications (RFA) for research to understand and enhance vaccine-related therapies for AD prevention.

Research on tau, the protein that forms the other major AD lesion, the neurofibrillary tangle, has also accelerated this year. Mutations in the tau gene have been shown to cause some forms of another late-onset dementia. A transgenic mouse strain was developed in the past year that expresses one of the human tau mutations and develops AD-like tangles. This animal model will help researchers understand why tangles form and what role they play in the pathology of AD and other dementias.

Understanding the subtle physical changes that accompany aging and developing treatments to address these changes may also be useful in treating early stages of other neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease. For example, new results from a study on reversing the age-related shrinkage and dysfunction of certain brain cells that produce the memory-related chemical messenger acetylcholine show that nerve growth factor can reverse the age-related reduction in transport of acetylcholine from these cells to different parts of the brain important to attention and memory. This approach is now being tested in a small industry-funded clinical trial. Results from another recent breakthrough have shown that, contrary to prior belief, the nervous system retains the ability to make new neurons even in old adults. This research has uncovered environmental factors such as exercise that can increase the numbers of new brain neurons, improving memory function in adult mice. Studies are beginning to unravel the molecular steps that control the production of new neurons in different areas of the nervous system, including the spinal cord. These findings are major steps forward not only to enhancing nerve cell development, but also to replacing nerve cells lost through age, trauma, or disease.

Major breakthroughs in our understanding and treatment of AD are coming from identifying the mutated genes responsible for early onset AD. In the more common late onset form of AD, a combination of risk factor genes and non-genetic factors seems to be key. In the early 1990s, APOE4 was identified as the first major risk factor gene for late onset AD. In the past year, three groups simultaneously discovered a region containing another risk factor gene on chromosome 10. Identifying this gene and other still unknown risk factor genes will lead to greater understanding of the molecular processes underlying AD, and will result in new treatment strategies, some of which will likely be tailored to an individual’s unique genetic profile. New risk factor genes will also lead to better prediction of a person’s individual genetic risk profile for AD. Strategies are being developed for large-scale collection of appropriate families and analysis of genetic data for these studies.

Drug discovery, development and testing

The only currently FDA-approved treatments for AD are tacrine, donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine, each of which boosts levels of acetylcholine, the chemical messenger involved in memory. However, there are currently many drugs at various stages of testing that have shown promise in either treating the symptoms associated with AD or slowing the progression of the disease. To screen as many potential drugs as possible, the NIA has developed the infrastructure for preclinical drug discovery and testing for drug safety in animals. Pilot and planning mechanisms have also been developed, along with NIMH and NINDS, to facilitate development of full-scale clinical trials, and this year, the first pilot clinical trials have been funded through this mechanism.

NIA supports AD clinical trials through a variety of mechanisms. In addition to individual investigator-initiated clinical trials, the NIA supports the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS), established to support multi-site clinical trials on compounds that large pharmaceutical companies generally would not test. The ADCS is also designed to develop and test new instruments for effective clinical trials. Several clinical trials now in progress are being supported by the NIA through the ADCS. The ADCS has also been key in developing standardized procedures and measurements in clinical trials, widely accepted in both academia and in industry. The ADCS will continue to be an important part of NIA support of large-scale AD prevention trials as well as the search for biological markers for monitoring the efficacy of drugs in clinical trials.

Early AD Diagnosis

Much of our understanding of the clinical course of AD and the underlying brain pathology comes from longitudinal, interdisciplinary studies of persons with AD and normal controls. Many of these studies have been coordinated through the NIA-funded Alzheimer’s Disease Centers. A newly-funded collaborative infrastructure, the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, is enhancing collaboration among the Centers to study important new areas of research. One such area involves understanding the preclinical stages of AD, a major new frontier in AD research and of the utmost importance in implementing future preventative treatments.

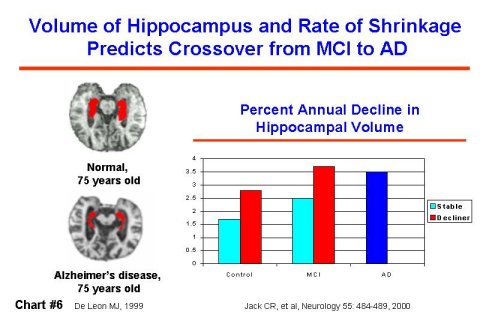

Recent advances in imaging and in clinical and pathological assessment are focusing on identifying persons diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) accompanied by memory impairment. Prevalence estimates show that there are as many persons with MCI as there are persons with a clinical diagnosis of AD. In one study, 80% of persons diagnosed with MCI had developed clinically diagnosed AD within eight years. Distinguishing between persons with MCI who will and will not progress to AD is a critical objective. In a recently published study, the degree of impairment found in clinical assessment predicted those who would develop AD more rapidly; and in an imaging study of persons with MCI, the smaller a particular brain region at the beginning of the study, the greater the risk of developing AD later. (Chart #6) Abnormally low brain activity, identified by positron emission tomography (PET) scanning, may be able to identify abnormal patterns of activity predictive of later AD diagnosis earlier than other currently available tests.

Besides their potential utility in early diagnosis, these imaging techniques are also being assessed for their ability to determine the effectiveness of early treatments or interventions, such as those being tested in the AD Prevention Initiative. Investigators believe that they may be more rapid and cost-effective indicators of treatment efficacy than conventional measurements.

Risk and Protective Factors

Recent epidemiology studies focus attention on cardiovascular risk factors such as high blood pressure in middle age and elevated cholesterol as risk factors for AD. Further animal and human studies and clinical trials will be required to determine if AD and cardiovascular disease share common risk factors and possibly concurrent intervention strategies. One approach to identifying causal factors is to compare populations with very different life styles. One recent study showed that the rate of AD diagnosis was approximately half in an urban population of older Africans in Nigeria than it was in African Americans of Nigerian origin now living in Indianapolis. The Africans in the study had much lower prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol and diabetes than did the U.S. population. Future studies will pinpoint exactly which of these or other factors was responsible for the difference in AD development between the two groups.

Early life environment has been implicated as a risk factor for several late life chronic diseases. Socioeconomic or environmental variables may affect brain growth and development, perhaps affecting the risk of developing AD in later life. Other life course variables such as exposure to environmental toxins or traumas may increase susceptibility to cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases in later life. One risk factor may be severe head injury, as shown by a recent study of World War II Veterans. Recent studies correlate a number of other variables including education, occupation, leisure mental activities and social support systems with the risk of cognitive decline or AD. Evidence that particular environments or lifestyles would reduce the risk or delay the onset of AD would have enormous implications for lifestyle changes to maximize healthy cognitive aging. Older Americans already have better education and health and are less disabled than in previous generations. It is possible that one or more of the above factors may already be causing a lower prevalence of severe cognitive decline in the elderly than would have been predicted from earlier studies.

Patient Care Strategies and Caregiver Burden

Perhaps one of the greatest costs of Alzheimer’s disease is the physical and emotional toll it takes on family, friends, and other caregivers. There is clearly a critical need to develop more effective behavioral and pharmacological strategies to treat and manage problem symptoms in people who have AD and to alleviate caregiver burden. This is one of the major goals of the NIH Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative. (Chart #7)

Agitation and sleep disturbance are two of the major behavior problems in AD patients that increase caregiver burden. Two clinical trials are determining whether drugs can reduce agitation in patients with AD. In another small trial, melatonin is being tested for reduction of sleep problems in patients with AD. In other studies focusing on elderly caregivers of patients with dementia, moderate-intensity exercise showed marked improvements in caregiver physiological reactions to stress and in sleep quality when compared to a control group maintained on a nutrition program. In another controlled trial, caregivers given web-based support experienced significantly reduced strain, while greater use of the support system resulted in lower strain among caregivers who lived alone with care receivers. To make the web more accessible to older caregivers, the NIA and National Library of Medicine are testing a senior- friendly web site model that features information about Alzheimer’s disease and caregiving. The project will be launched later this year.

As part of the AD Prevention Initiative, the NIA, in collaboration with the National Institute of Nursing Research, is supporting the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) initiative. This large, multi-site intervention trial is testing the effectiveness of different culturally sensitive home and community-based interventions for families providing care to loved ones with dementia. The interventions that are being tested include psychological education support groups, behavioral skills training, family-based systems interventions, environmental modifications, and technological computer-based information and communication services. Some 1,000 families are enrolled in the REACH study, including large numbers of African-Americans and Hispanics. Results from the REACH study will be available in the next year, and I look forward to sharing any significant advances with the Congress and the general public.

In conclusion, the pace of scientific discovery in the area of Alzheimer’s disease research has further accelerated this year and optimism is growing that effective treatment may follow from the current generation of clinical trials. Much remains to be understood about the underlying causes of AD, and the NIA continues to support a spectrum of basic and clinical research aimed at comprehending the multifaceted factors interacting throughout the lifespan to cause AD. Only by understanding these varied factors will we be able to develop the most effective and safe strategies for defeating this much-feared scourge of later life. I am happy to answer any questions you may have at this time.

1 Evans, D.A., Estimated prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in the US. Milbank, Q. 1990;68:267-289.