Press Release 06-048

Scientists Discover Interplay Between Genes and Viruses in Tiny Ocean Plankton

Finding leads to new conclusions about marine environment

March 23, 2006

New evidence from open-sea experiments shows there's a constant shuffling of genetic material going on among the ocean's tiny plankton. It happens via ocean-dwelling viruses, scientists report this week in the journal Science.

Conducted by biological oceanographers Sallie Chisholm and her colleagues at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the research is uncovering a new facet of evolution and helping scientists see how microbes exploit changing conditions, such as altered light, temperature and nutrients.

"These results tell us that even the smallest organisms show genetic variation related to the environment in which they exist," said Philip Taylor, director of the National Science Foundation (NSF)'s biological oceanography program, which funded the research.

In addition to NSF, support for the research came from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and from the U.S. Department of Energy.

"Our image of ocean microbes and their role in planetary maintenance is changing," Chisholm said. "We no longer think of the microbial community as being made up of species that have a fixed genetic make-up. Rather, it is a collection of genes, some of which are shared by all microbes and contain the information that drives their core metabolism, and others that are more mobile, which can be found in unique combinations in different microbes."

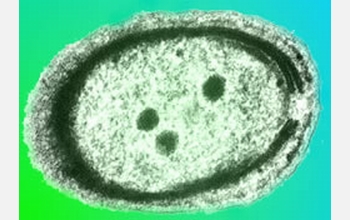

The distributors or carriers of new genes, the scientists suspect, are the massive numbers of viruses also known to exist in seawater. Some of them are adept at infecting ocean microbes like Prochlorococcus, the sea's most abundant plankton species. The ocean viruses, which carry their own genes as well as transport others, provide a way of transferring genes from old cells into new ones.

"We're beginning to get a picture of gene diversity and gene flow in Prochlorococcus," Chisholm said. "These photosynthesizing bacteria form an important part of the food chain in the oceans, supply some of the oxygen we breathe, and play a role in modulating climate. It's important that we understand what regulates their populations. Genetic diversity seems to be an important factor."

In one report, Chisholm and scientist Maureen Coleman suggest that gene-swapping in ocean microbes resembles the flow of genes already known to occur among disease-causing bacteria. In an ocean habitat, the exchange offers marine microbes a diverse palette of potential gene combinations, each of which might be best suited for a particular environment. "This would allow the overall population to persist despite complex and unpredictable environmental changes," said Chisholm.

A second report, by Zackary Johnson and Erik Zinser, compares where Prochlorococcus microbes are found with the conditions under which they thrive. These geographic patterns relate to environmental variables such as temperature, predators, light and nutrients.

Chisholm is trying to learn how the microbes function as a system in which they have co-evolved with each other, and with the chemistry and physics of the oceans. The studies show that all Prochlorococcus strains are very closely related, yet they display an array of physiologies and genetic diversity, Chisholm said.

"Genetic diversity is at the heart of the extraordinary stability of Prochlorococcus in the oceans, which maintain steady population sizes over vast regions of the sea," she said.

-NSF-

Media Contacts

Cheryl Dybas, NSF (703) 292-7734 cdybas@nsf.gov

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent federal agency that supports fundamental research and education across all fields of science and engineering, with an annual budget of $6.06 billion. NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to over 1,900 universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives about 45,000 competitive requests for funding, and makes over 11,500 new funding awards. NSF also awards over $400 million in professional and service contracts yearly.

Get News Updates by Email Get News Updates by Email

Useful NSF Web Sites:

NSF Home Page: http://www.nsf.gov

NSF News: http://www.nsf.gov/news/

For the News Media: http://www.nsf.gov/news/newsroom.jsp

Science and Engineering Statistics: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards Searches: http://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/

|