The White-Nose Syndrome Mystery:

Something Is Killing Our Bats

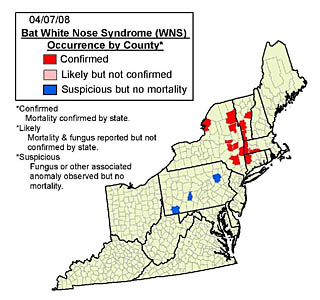

Tens of thousands of hibernating bats died this winter in the northeast, and we don't know why. In and around caves and mines in eastern and upstate New York, Vermont, western Massachusetts, and northwestern Connecticut, biologists found sick, dying and dead bats in unprecedented numbers. In just eight of the affected New York caves, mortality appears to range from 80 percent to 100 percent since WNS was first documented at each site, based on winter surveys.

These bats often have a white fungus on their muzzles (hence the name "white-nose syndrome") and other parts of their bodies. Despite the continuing search to find the source of this condition by numerous laboratories and state and federal biologists, the cause of the bat deaths remains a mystery.

|

Credit: Al Hicks, New York Dept. of Environmental Conservation

|

Bats are an important part of our ecosystem. One bat may eat from 50 percent to 75 percent of its body weight in flying insects a night during the summer months. Because females produce just one pup a year, the plunging number of bats — apparently as many as 90 percent loss in some hibernacula — translates into a crisis in bat populations in four states with no end in sight and potentially far-reaching effects, an ecological disaster in the making. This summer we may notice an absence of bats from our night sky, and what will that mean for us?

At least one of the affected species, the Indiana bat, is protected by the Endangered Species Act. Little brown bats, the most numerous bats in the Northeast, are sustaining the largest number of deaths. Also dying are northern long-eared and small-footed bats, eastern pipistrelle and other bat species using the same caves.

Biologists are not certain if the bats are transmitting white-nose syndrome among themselves, if people are the vector, if both bats and people are spreading it, or if it is comes from some other source. Affected dead and dying bats are usually emaciated, and those found outside are often severely dehydrated.

|

| Credit: courtesy of Cal Butchkoski, Pennsylvania Game Commission |

At the beginning of April 2008, we had identified white-nose syndrome in 18 sites in New York; five sites in Vermont; three sites in Massachusetts; one site in Connecticut; and three possible sites in Pennsylvania. The states of New York, Vermont, Connecticut and Massachusetts are investigating the geographical extent of the outbreak, revisiting sites to determine the amount of mortality, and providing bat specimens to laboratories throughout the United States for analysis to help determine the cause of bat deaths.

This summer, people are reporting dead and dying little brown bats at their summer roosts in attics, barns and other outbuildings in the four states with confirmed white-nose syndrome and in New Hampshire and Pennsylvania, neither of which have confirmed white-nose syndrome in winter hibernacula. While doing surveys of forested areas, biologists have also caught bats with abnormal wing tissues, including white spots, holes and tears. We are also seeing a higher than usual number of pups falling and dying. We do not know if these summer bat deaths are directly caused by white-nose syndrome or if the bats are weakened from fighting off white-nose syndrome in the winter hibernacula and have not been able to recuperate. This summer, people are reporting dead and dying little brown bats at their summer roosts in attics, barns and other outbuildings in the four states with confirmed white-nose syndrome and in New Hampshire and Pennsylvania, neither of which have confirmed white-nose syndrome in winter hibernacula. While doing surveys of forested areas, biologists have also caught bats with abnormal wing tissues, including white spots, holes and tears. We are also seeing a higher than usual number of pups falling and dying. We do not know if these summer bat deaths are directly caused by white-nose syndrome or if the bats are weakened from fighting off white-nose syndrome in the winter hibernacula and have not been able to recuperate.

The bat conservation community is concerned and involved in exploring the possible cause of the disease and raising funds to assist in the research. National and regional caving organizations are coordinating with state biologists to help assess the situation, providing the most current information to the caving community regarding advisories, and documenting cave visitations to determine if cavers could be spreading the cause of the outbreak.

If you have observed potential signs of white-nose syndrome in bats during a caving trip, or if you have dead or dying bats in your area, send information to us.

|