|

|||||||||

skip to content |

|||||||||

A River In The Sea

Sea Grant-Funded Researcher Takes New Look At Impact of Wintertime Coastal Currents

Photo by Chris Linder

All in all, physical oceanographer Glen Gawarkiewicz admitted, he could have decided on a research topic more conducive to warm days in the bright blue waters of the Caribbean, drifting along with the lazy currents in and amongst the coral reefs.

But when you’re interested in how seasonal cooling and storms affect the density of seawater, the seawater you’re interested in is just off Cape Cod and the season you’re interested in is winter, well, then you prepare for the worst and hope for the best.

For Gawarkiewicz, a Senior Scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, that meant 12-hour days beginning and ending in the dark, rough seas, and pitching decks.

The reward for his efforts in the Sea Grant funded project, though, was some surprising insights into the way the seawater off the Cape reacts in the wintertime, especially in the impact that freshwater currents have on the salinity and density of near-coastal waters. During this project Gawarkiewicz worked closely with a former post-doc, Andrey Shcherbina, and Research Associate Chris Linder.

The same type of processes that we’re seeing

here on the Outer Cape are going on in the Arctic,![]() Gawarkiewicz

said, since freshwater melt from glaciers creates a similar current to

that of the Maine rivers.

Gawarkiewicz

said, since freshwater melt from glaciers creates a similar current to

that of the Maine rivers.![]() It’s

a nice natural lab for what occurs (in the Arctic).

It’s

a nice natural lab for what occurs (in the Arctic). ![]()

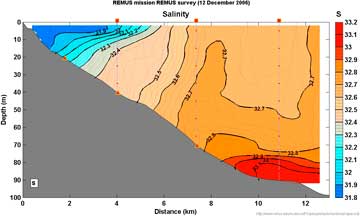

Gawarkiewicz, utilizing the autonomous underwater vehicle REMUS (Remote Environmental Monitoring Units) and several moorings, expected to see wintertime “mixing” of salinity and temperatures, thanks to factors such as atmospheric cooling, strong winds, and storms. That, he believed, would make the area next to the coast cooler and denser, wiping out the coastal current.

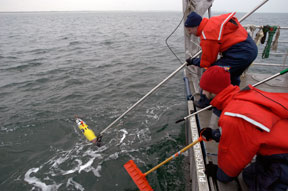

The REMUS 100 vehicle specially-equipped for studying coastal and shelfbreak physical oceanographic processes. The vehicle can travel at a speed of 4 knots and go to a depth of 90 meters. It carries a number of scientific instruments and can measure temperature, conductivity (for salinity), and ocean currents above and below the vehicle. (larger image)

Recovering the REMUS after a successful mission. Al Plueddemann hooks the handle of the REMUS so that it can be safely lifted onto the deck. Andrey Shcherbina waits to prevent the REMUS from colliding with the stern of the R/V Tioga. Photos by Chris Linder

Instead he saw a current that fought back – and hard.

There was a wedge of “lighter” freshwater coming from rivers in Maine, like the Penobscot and Kennebec, driven south by buoyancy differences which hugged the beaches on the eastern end of Cape Cod. At times, Gawarkiewicz said, it was so apparent he could even see a visible line of foam and re-circulating debris between the two.

“Fresh water comes out of Maine and takes a right turn and when that current hits the area off the Cape it hits a choke point,” Gawarkiewicz said.

And that’s where things get interesting.

Over the course of the winter, he found, there is a narrower band of freshwater, as the current decreases in strength and width because of less input from the sources in the north. As a result, the fresher water would creep up against the coast until about March. Later in the spring, there is a major influx of freshwater due to snowmelt and the current widens and strengthens. However, the persistent coastal current has a big effect on the density of the seawater near the coast.

The coastal current, which is fresh and less dense, prevents the winter cooling from making dense water along the coast. But the cooling does tend to increase density and drive those denser waters into deeper water offshore of the coastal current.

“So there’s a battle going on over the shelf,” Gawarkiewicz said.

The information gleaned off the Cape, he said, has wide-ranging implications, both scientific and societal and fits in well with the Sea Grant mission.

The Gulf of Maine Coastal Current often carries Harmful Algae Blooms, the infamous “Red Tide” that decimates shellfishing areas. In 2005, an HAB did nearly $30 million in damage in the Bay State alone. While these do not occur in winter, the winter processes affect stratification in the central Gulf of Maine, which in turn impacts the structure of the coastal current in the spring and summer.

In addition, fishermen are interested in what occurs within the currents to help determine where fish might be located.

“Understanding this coastal current throughout the year is important because it ties into so many ecosystems,” he said, adding that working on the project has allowed him to meet with the general public, harbormasters and decision-makers in one fell-swoop. “It’s a project with local impact at its best.”

But the impact goes beyond the Gulf of Maine, especially in this time of concern about climate change.

“The same type of processes that we’re seeing here on the Outer Cape are going on in the Arctic,” Gawarkiewicz said, since freshwater melt from rivers and glaciers creates a similar current and environment to that coming out of rivers in Maine. “It’s a nice natural lab for what occurs (in the Arctic).”

Gawarkiewicz said there are many opportunities for additional research in the currents, which are nutrient rich, but finding takers to join him was near impossible – for this project, at least.

“Oddly enough, no one wants to go out with us,” he said with a laugh. “Now, my Belize project – there was lots of interest in that.”

CONTACT:

Dr. Glen Gawarkiewicz

Clark 343C

360 Woods Hole Rd., MS #21

Woods Hole, MA 02543

gleng@whoi.edu

SITES OF INTEREST:

http://www.whoi.edu/instruments/viewInstrument.do?id=1759

http://www.whoi.edu/science/PO/people/ashcherbina/capecod/index.html

|

The Woods Hole Sea Grant program, based at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), supports research, education, and extension projects that encourage environmental stewardship, long-term economic development, and responsible use of the nation’s coastal and ocean resources. It is part of the National Sea Grant College Program of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, a network of 32 individual programs located in each of the coastal and Great Lakes states. Together, these programs form a national network of over 300 participating institutions involving more than 3,000 scientists, engineers, educators, students, and outreach experts. Locally, Sea Grant’s affiliation with WHOI began in 1971 with support for a number of individual research projects. In 1973, WHOI was designated a Coherent Sea Grant Program and, in 1985, was elevated to its current status as an Institutional Sea Grant Program. The Woods Hole Sea Grant Program has made great strides to channel the expertise of world-renowned ocean scientists toward meeting the research and information needs of users of the marine environment. Public and private institutions throughout Massachusetts, and the northeast region, participate in the Woods Hole Sea Grant Program. |

3/24/08

CLIMATE · OCEANS, GREAT LAKES, and COASTS · WEATHER

and AIR QUALITY

ABOUT US · RESEARCH

PROGRAMS · EDUCATION · HOME