|

|||||||||

skip to content |

|||||||||

UNH Researcher Is Mapping the Flow of Communication

Troy Hartley shows a computer-generated “map” of communication networks for coastal and ocean management organizations. The communication can include complex directives from project coordinators or simple discussions around the workplace water cooler. Credit: Rebecca Zeiber, NH Sea Grant

Daily communication network map involving herring management, a large regional fisheries case. Approximately eight subgroups or clusters of individuals speak daily, principally organized around stakeholder groups/agencies. Credit: Troy Hartley

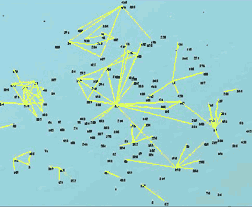

The network map for herring management depicting weekly communication. There are more than 150 individuals from industry, government, conservation groups, scientists and other stakeholder groups involved at various levels on a weekly basis. This map shows how communication is linked between stakeholder groups and the central cluster. Credit: Troy Hartley

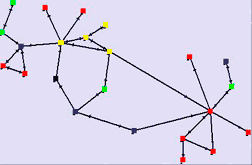

Weekly communication map for the New Hampshire Coastal Watershed Land Conservation Planning group. Twenty-three individuals are closely linked to one another through frequent interaction to form a tight cluster of communication. Credit: Troy Hartley

Troy Hartley could be considered a cartographer of human communication.

Hartley, a University of New Hampshire research assistant professor in the Department of Resource Economics and Development, is studying the patterns of communication within and between various local and regional organizations.

Communication ‘maps’ make sense to people.

They create a visual of something that is conceptually difficult to wrap

your arms around.![]()

--Troy Hartley

Funded in part by NH Sea Grant, his project was motivated by the U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy report that indicated effective coastal and ocean management is inhibited by a lack of communication, coordination and a sense of partnership. Specifically, Hartley is looking at the communication networks for projects undertaken by the Atlantic Marine Fisheries Commission, the New England Fisheries Management Council, the NH Coastal Program and the Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia.

Hartley used interviews and surveys to measure communication patterns among individuals within these entities and projects. The frequency and directional flow of information within and between the key individuals, such as project coordinators, scientists and decision-makers, were then “mapped” using the computer program Inflow.

The outcome depicts a spider web effect of points connected by lines in a network. The points represent the individuals and the lines represent information flow on daily, weekly or monthly time scales.

“Communication ‘maps’ make sense to people,” Hartley explains. “They create a visual of something that is conceptually difficult to wrap your arms around. We struggle to find the best ways that people can communicate and coordinate effectively on a regional scale. We need to get better at that for regional integrated coastal and ocean management to become a reality.”

The maps depicting the channels of communication among individuals in a New Hampshire watershed planning organization show relatively tight communities among participants who know of each other well and interact frequently. The maps show lots of lines crisscrossing and forming a tight cluster of communication with many individuals talking with each other.

On the other hand, Hartley shows a communication network map involving herring management, a large regional fisheries case involving more than 150 individuals. The lines depicting the flow of communication show dense clusters of activity with fewer lines connecting the clusters to one another than was observed in the watershed planning case.

“Participants involved with herring management have very specialized roles and interests,” Hartley explains. “A lot of the network weight falls on certain individuals to keep the communication flowing. The network is vulnerable to their status and availability.”

Hartley says the results of the research will encourage strategic thinking about network design and recommend changes in the function of the network and roles of individuals.

“I enjoy seeing what the maps can do for people to improve communication within and among regional government entities,” Hartley adds. “We can work in a coordinated way and the maps give us the guidance to get there.”

Hartley will be taking his expertise down to the Virginia Institute of Marine Science later this year when he joins Virginia Sea Grant as their new Director.

|

New Hampshire Sea Grant provides support, leadership and expertise for marine research, education and extension. A component of the National Sea Grant College Program, it is one of a network of 30 programs promoting the understanding, development, wise use and conservation of our ocean and coastal resources. |

5/5/08

CLIMATE · OCEANS, GREAT LAKES, and COASTS · WEATHER

and AIR QUALITY

ABOUT US · RESEARCH

PROGRAMS · EDUCATION · HOME