The Falcon’s Lair

Monday, July 14th, 2008July 14, 2008

St. Mary’s County, MD

My jaw was long and razor-burned, my hair a brownish pond icing up from the temples in. I looked rather pleasantly like a salt-and-pepper satan. I was tailing Sam Hammett down Great Mills Road in St. Mary’s County, Md., where he was born, but the trail was a hundred years cold.

Everywhere I went, I got “Sam who?” After a day of chasing played-out leads and a night at some fleabag, I was fed up and on my way out of town. While my imaginary Argentine secretary, Effie Peron, ducked into a filling station to powder her nose, I called the last number I had for the county tourism bureau. A courtly man with an accent like crab cakes and clotted cream answered. Louis Buckler, he called himself, and asked me my business. I told him.

“The Hammett place?” he said. “Try up Indian Hill Road. Big house, two or three stories, with a wing on the side. Two chimneys, even.”

“You mean it’s still standing?”

“Standing? Hell, it’s still in the family.”

I took the directions down and pointed my motor accordingly. A house approximating Buckler’s description loomed up on the left. We were barely out of the car when a couple with a child emerged and made us welcome.

“I’m Connie Little,” the frail said, extending a hand. “I’m the librarian around here.”

I introduced myself and brandished a buff-colored card at them.

“You’re from The Big Read?”

Grudgingly I allowed as how I was. It’s getting harder and harder to keep my hatbrim down and get a simple job done, what with all the hoopla about the Read, but the hell with it.

“So this isn’t Hammett’s house?”

“No, that’s back along Great Mills Road. Watch for the historical marker about him.”

“There’s a sign about him?”

“You can’t miss it.”

Effie said, “He already did.”

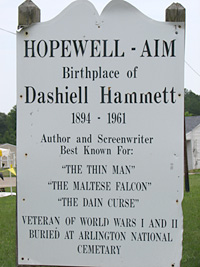

She folded her legs back into the passenger seat of the sedan with no great urgency, and we backtracked to Great Mills. It’s amazing how different a stretch of road can look when you’re headed back down the way you came. If I’d been the philosophical type, I might have made something of that. Sure enough, up ahead on the right was a weathered white sign marking Hammett’s birthplace.

|

|

|

A wooden sign commemorates the Hammetts’ ancestral pile, Hopewell & Aim. No points deducted for spelling, but the omission of “Red Harvest” seems a shame. Photo by David Kipen. |

We snapped the marker with my Kodak and got back into my machine. Just as Buckler had described it – but nowhere near where he’d put it – down a dead end next to a driving range stood the house. It had seen better days, but you would have too, after all that time. I went around back and found a polite but wary woman there, picking cucumbers. She identified herself as a descendant of the family who’d bought out the Hammetts, and surrendered her name. It wasn’t his.

So much for Buckler’s story about Hammetts still on the premises. Together she and I circumambulated the property. On one side was a small manmade lake, on the other a jumble of rusting farm equipment. The man of the house came onto the porch, blinking. We stood there, me, Effie and the two of them. I didn’t know what I’d come for, but this wasn’t it. A squirrel scampered around a tall outdoor cage. The woman noticed my attention and answered it.

“He likes it here. We only lock him up on account of the dogs.”

Just then a gunshot echoed across the lake.

“That’ll be the sportsman’s club. It’s hunting season.”

I talked my way into the place. It was as if a 200-year-old farmhouse had eaten a suburban bungalow whole and washed it down with a swig of air freshener. The only trace that remained of the house Hammett grew up in was the view from a second-floor window above the front porch. I stared out of it a long time.

I’d come on a bad tip that led to a good one, with a dead writer in my head and an imaginary woman by my side. It was good to be there, hearing the gunfire, kidding myself that it all added up to something. My hostess tried to spook me with stories about weird noises at night, but I wasn’t biting.

Above the second-floor landing was a locked rectangular trapdoor, painted brown and scored with scratches. I tried to get a runelike symbol on it to look like an H, but no dice. Some doors you just can’t open. I was trying to picture Hammett up in the attic as a kid, woolgathering out the window, that week’s library books freshly devoured at his side. I took a picture of the trapdoor and hoped the snap might tell me what the original wouldn’t.