TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

OVERVIEW OF TREATMENT PROGRAM

METHODOLOGY

Design and Analysis

Assessment

Clinical Factors

TYPES OF TREATMENT

Brief Interventions

Behavioral Treatments

Nonbehavioral Psychotherapy

Support Networks

Program Portfolio

Pharmacotherapy

Program Portfolio

SELECTED TREATMENT TOPICS

Adolescent

Special Populations

Alcohol and Smoking

Program Portfolio

Comorbidity

Self-Help Groups

Natural Resolution

REFERENCES

APPENDICES

A: Subcommittee for Review of Treatment Portfolio

B: Experts in Treatment

C: NIAAA Program Staff

D: NIAAA Staff and Guests

TREATMENT

REPORT OF A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE NATIONAL ADVISORY COUNCIL

ON ALCOHOL ABUSE AND ALCOHOLISM

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism's (NIAAA) Subcommittee for the Review of the Extramural Research Portfolio for Treatment met on November 8-9, 1999. The charge to the Subcommittee was to examine the appropriateness of the breadth, coverage, and balance of the treatment portfolio, identifying research areas that are well covered and others which are either under-investigated or which otherwise warrant significantly increased attention. The Subcommittee was asked also to provide specific advice and guidance on the scope and direction of the Institute's extramural research activities in the treatment area.

The Subcommittee for the Review of the Extramural Research Portfolio for Treatment consisted of two co-chairs, NIAAA Advisory Council member, and an advisory group of six individuals. Three of these individuals have demonstrated expertise in alcohol-related areas, and three individuals have demonstrated expertise in non-alcohol-related areas (see Appendix A).

The review process was initiated by having experts (see Appendix B) in treatment prepare written assessments of the state of knowledge, gaps in knowledge, and research opportunities. NIAAA program staff (see Appendix C) presented the current extramural portfolio, categorized into the areas of policy, problem areas, youth and media, special populations and basic research and methodology, and training and career development. All information was shared with experts, selected NIAAA staff, and the co-chairs and advisory group before the meeting.

A summary of FY 99 treatment awards is detailed below.

|

Treatment |

Percentage of

Treatment to Total |

No. Amount

(in thousands) |

No. Amount |

|

Research Project Grants1 |

72 |

$22,703 |

12% |

14% |

|

Cooperative Agreements |

11 |

5,844 |

92% |

49% |

|

Research Centers |

2 |

3,322 |

14% |

14 % |

|

Research Careers |

13 |

1,629 |

19% |

22% |

|

Research Training |

6 |

1,290 |

10% |

20% |

|

Total |

104 |

$34,788 |

14% |

17% |

1 includes SBIR awards and reimbursable funds.

On November 8-9, 1999, experts and NIAAA program staff made abbreviated presentations of their material followed by discussion among all of the participants, including representatives from other NIH Institutes and guests (see Appendix D). After completing this process, the co-chairs and advisory group, with input from the experts, delineated the following list of research priorities, in order of importance.

PRIORITIES RESULTING FROM REVIEW OF

TREATMENT PORTFOLIO

- (1) Mechanisms of Action of Treatments. Over the last decade, there has been considerable progress in identifying effective psychosocial and pharmacological treatments for alcoholism; however, the specific theory-driven mechanisms of action are often poorly understood. For continued progress in treatment development, it is critical to develop a better understanding of the biological, psychological, behavioral, social and environmental mechanisms of these interventions and to develop more accurate models of treatment and placebo effects. Examples of such research include: elucidation of causal chains underpinning treatment effects; testing of mediators and moderators of therapeutic processes; determining the relative contributions of skills training versus motivational enhancement to treatment outcomes; and clarifying the additive and subtractive effects of complex therapies. Development of new or enhancement of existing, theory-based behavioral interventions including psychotherapies, behavior therapies, cognitive therapies, and family therapies is needed.

(2) Combinations and Sequencing of Treatments. Current alcoholism treatments generally have been found to have modest effects. By combining and or sequencing treatments, it may be possible to enhance outcomes. Research is needed on theory-based therapeutic models of combined treatment or stepped care, particularly focused on tailored interventions for special populations. Combined interventions can include behavioral, cognitive, psychotherapy, support network or pharmacological treatments. Interactive mechanisms of action should be clarified. Combined treatments will first require efficacy testing and, at a later stage, studies to determine their transportability. Such studies may test whether a combined treatment shown to be efficacious in a controlled setting can still be effective when transferred to the community.

(3) Health Seeking Patterns and Processes. It is evident that the majority of individuals with alcohol-related problems change their drinking patterns and associated problems without intensive formal treatment intervention, either through natural resolution or brief motivational interventions in health care and other settings. It is critical to develop a better theory-based understanding of these natural change efforts and health-seeking behaviors. Key areas of research include factors that promote and sustain movement towards recovery, processes of care engagement (e.g., proactive versus reactive approaches), compliance with care recommendations, retention in change processes and maintenance of change. Research also is needed on the role of community-based recovery networks (e.g., self-help and mutual-help groups) in these processes, including their role in treatment, long-term effects and cost-effectiveness models.

(4) Concurrent Disorders. Individuals with alcohol use disorders have exceptionally high rates of co-occurring disorders, including medical comorbidity, nicotine and other drug disorders, and psychiatric disorders. Research is needed to: better understand patient characteristics associated with different concurrent disorders (e.g., diagnostic status, biological status, phenotyping, developmental staging); elucidate the effects of concurrent disorders on alcoholism treatment outcomes; understand the process of change in the non-alcohol comorbid disorder; and develop specialized interventions for comorbid patients. In addition, assessment instruments and methods need to be enhanced to measure the broader range of characteristics and outcomes relevant to this population.

(5) Help Agent Behaviors. Although it is well recognized that change processes and outcomes are affected by helping agents (e.g., therapist, health care provider, clergy, family member, concerned significant other), this area of research has received little attention within the alcoholism field. Theory-driven models for assessment of provider effects are needed and could include provider attributes (characteristics, cognition, and beliefs), processes between client and provider, and training or interventions aimed at the change agent. Design innovations (e.g., learning from expert providers) and statistical strategies must be developed to address the methodological problems inherent in this line of research.

Issues that cross-cut across the priorities:

Special populations (e.g., gender, minorities, developmental stage)

Measurement

Matching

Technology transfer

Additional issues related to mechanisms of funding:

Stage 1 psychotherapy development based on basic behavioral sciences

Effectiveness studies under health services research portfolio

K-25 awards to promote biostatisticans' interest in alcoholism treatment

Awards for meetings -- biostatistics

Trans-Agency funding (DOD, VA, CSAT)

Trans-Institute funding (NIDA, NIMH)

Pharmaceutical industry

Back to Top

OVERVIEW OF TREATMENT RESEARCH AT NIAAA

(Richard Fuller, M.D. and John Allen, Ph.D.)

Historical Perspective

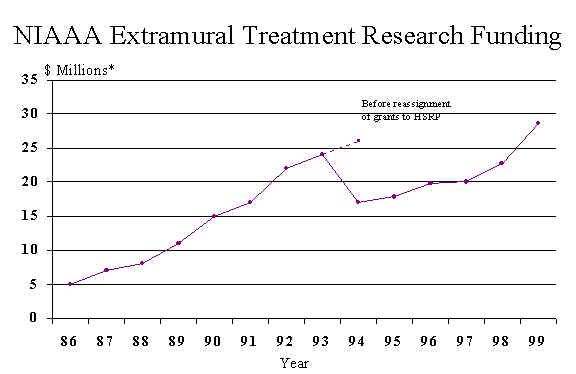

There was not a separate Treatment Research Branch (TRB) until the Division of Clinical and Prevention Research (DCPR) was established in 1987. Dr. Allen was appointed Chief of the Treatment Research Branch in 1987, and Dr. Fuller was appointed Director of the Division of Clinical and Prevention Research in 1988. At the time that the Treatment Research Branch was established, the NIAAA portfolio was primarily focused on behavioral treatments and was small in dollar amounts by today's standard ($4 million).

Two reports were influential in guiding the development of the TRB portfolio for the next decade. One was the "Report of the Fifth Ad Hoc Extramural Science Advisory Board on Treatment" and the other was the Institute of Medicine's report entitled "Prevention and treatment of Alcohol Problems Research Opportunities." (1989)

The first report summarized the existing knowledge and identified new areas of research. The Executive Summary of this report urged the following research goals: 1) "...giving special emphasis to the reliable classification of subtypes of alcoholics who can be matched to treatments in ways that maximize effectiveness...," 2)"Develop better measures of treatment outcome that are sensitive to changes in biological, social, and psychological functioning...," 3) "Identify and clinically evaluate new pharmacological agents, ...", 4) "Evaluate the effectiveness of...behavioral, psychosocial, and mutual help approaches...through randomized controlled trials...", 5) "Conduct carefully controlled studies to measure cost-benefits and costs offsets of alcoholism treatment," and 6) "Descriptive studies of treatment systems and service networks..."

How close has TRB come in meeting those objectives during the past decade?

(1) In his first year as Chief of TRB, Dr. Allen wrote the RFA to solicit applications of a multi-site patient-matching study. This led to Project MATCH that vigorously tested the matching hypothesis in a large sample.

(2) Better measures have been developed. One example is the DrInC, which identifies and quantifies the consequences of excessive drinking. There are many more examples. However, there is still no consensus on what outcome measures should be selected if one is limited to one or two, although percent days abstinent is commonly used.

(3) A large medications development program has been developed.

(4) A landmark randomized clinical trial of Alcoholics Anonymous was done. This trial was begun before TRB existed under the guidance of Dr. Ernestine Vanderveen, but was completed, and the results published during TRB's tenure. Project MATCH also provided insight into mutual help groups by testing Twelve Step Facilitation therapy. Project MATCH also tested two behavioral therapies: cognitive behavioral therapy and motivational interviewing. Project MATCH and the other TRB-supported clinical trials of behavioral and psychological therapies for alcoholism give us a firm understanding of efficacy of non-pharmacological therapies for alcohol dependence. What was missing until recently was a similar set of randomized studies of therapies for alcohol abusing and/or dependent adolescents. This major void has recently been corrected.

(5-6) These areas are now the responsibility of the Health Services Research Program.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report also advocated studies of patient-treatment matching and studies of treatment costs, benefits, and cost-offsets. The IOM report was silent regarding medication development. The report did identify a critical topic absent in the Extramural Advisory Board report, i.e., brief interventions. At that time, TRB was not supporting any research on brief interventions. Since then it has stimulated the field and several studies have been supported. The results from three of those studies have been published and confirm that brief interventions in primary medical settings in North America are effective in reducing alcohol consumption as has been found in several other countries.

The IOM report also briefly discussed smoking and posed three questions on treating smoking in alcoholics as research opportunities. The Treatment Research Branch recognizing the frequent co-occurrence of smoking and alcohol dependence and the serious impact of smoking on the health of alcoholics developed a research program addressing smoking and alcoholism.

In summary, we now have a better understanding of what treatment results can be expected from non-pharmacological treatments. An exciting medications development program now exists, the first fruit of which is the FDA approval of naltrexone to treat alcoholism. Studies done in North American now document the effectiveness of brief interventions. The efficacy of treatments for adolescents is now being addressed, as is the appropriate treatment for smoking in alcohol treatment programs. Finally, the methodology for doing treatment research has been improved, and these methods have become standard.

The primary activity of the Treatment Research Branch (TRB), like that of NIAAA's other extramural branches, is to support and monitor well-designed investigations related to alcohol abuse and dependence. Investigations are funded by mechanism of grants, cooperative agreements, and contracts. The graph on the next page reflects TRB financial support of projects since conception of the Branch to the present.

In addition to funding extramural investigations, the Branch performs three other important activities:

. Enhancement of Research Methodology

. Stimulation of Quality Research Proposals

. Dissemination of Research Findings

Enhancement of Research Methodology

Despite the extreme prevalence, societal cost, and suffering resultant from misuse of alcohol, until recent years research on alcoholism treatment tended to be of rather low scientific quality. Clearly this situation has now dramatically improved. Randomization, blinding, objective assessment, documentation of interventions, sophisticated data

analysis, etc., have now come to characterize studies in this field. TRB has attempted to contribute to the evolution of research methodology in such as:

- Publication of a primer addressing research design and statistical issues as they pertain to alcoholism treatment.

- Publication of a detailed handbook on alcoholism assessment instruments, including topical state-of-the-art reviews of the various domains of assessment, acceptable instruments, and presentation of psychometric and tests administration information by common data elements for each measure. (Much information from the handbook is also available on the NIAAA web site.) The assessment handbook is currently being updated and revised.

- Establishment with scientific community of guidelines for conducting investigations and reporting results on biochemical markers. These recommendations are encapsulated in an article published in Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research.

- Through a Treatment Replication, Validation, Evaluation Program (TRVEP) contract explored Marlatt's taxonomy of relapse precipitants and developed methodology for studying relapse to drinking.

- Convened a workshop on methodological issues surrounding research on assessment and treatment of adolescents with alcohol problems.

- Based on two meetings with members of the alcohol treatment research community developed a core battery of instruments recommended for inclusion in all studies dealing with medication development.

- Developed of a manual reflecting on experience in Project MATCH and addressing the critical topic of compliance with treatment research outcome evaluation.

- Published manuals on the Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC), a standardized measure of adverse consequences of drinking, and a computerized variant of the Timeline Follow-Back for assessing alcohol use (quantity, frequency, and peak intensity).

- Promulgated software and documentation for adaptive ("urn") randomization. This software can also assist researchers in realms of study outside of alcoholism.

Stimulation of Research Proposals

The Branch is constantly seeking to improve the number and quality of research proposals it can support. It has developed a large number of RFAs, PAs, and other solicitations identifying topics of particular concern. Equally important, staff members review and comment on concept papers submitted by candidate applicants. Additionally, members of TRB discuss research ideas and practical issues surrounding the grant application process by phone, via e-mail, as well as in public meetings.

To assure that there will be an abundance of quality proposals in the future, special efforts have been made to attract and assist promising young investigators. Strategies employed in this regard have included workshops to provide technical proposal writing skills, publication of R03 and R21 announcements for small awards to young investigators, and wide dissemination of SPIRIT, the NIAAA mentoring software to assist applicants in developing competitive proposals.

Additionally, Branch personnel consult extensively with applicants interested in refining grant proposals that have not yet earned scores in the fundable range.

Dissemination of Research Findings

As more is learned about effective treatment for alcoholism it has become incumbent on the Branch to disseminate findings to both the research community as well as to the treatment practice community.

The primary means of sharing findings with the research community are through scientific journal reports, monographs, and formal meetings with senior researchers in a topic area. Staff have published several important topical reviews of the literature and present regularly at national and international scientific meetings. Recent monographs published by TRB personnel have dealt with dynamics of relapse, adolescent treatment issues, and concurrent alcohol and nicotine dependence. A monograph in process focuses on craving. Formal meetings of late have dealt with issues such as assessment, medications, spirituality, biochemical markers, and craving.

It is more difficult to disseminate research findings to the treatment community due to its size and dispersion. Nevertheless, recent important contributions in this area have included two articles published in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, a counselor-oriented periodical, and presentation of research findings at several national and international meetings, ASAM's state of science conference, and the grand rounds of several hospitals. Perhaps the most important initiative dealing with enhancement of treatment services based on research findings were meetings last year with Hawaii and New York State policy makers and treatment providers. It is expected that this latter meeting will prompt development of a demonstration of research-based treatment for alcoholism to be implemented in several community-based treatment programs.

Treatment manuals for the three interventions employed in Project MATCH as well as the Assessing Alcohol Problems, the assessment handbook noted above, have also been widely distributed throughout the treatment community in the U.S. and overseas and have received broad acceptance.

Back to Top

METHODOLOGY

RESEARCH DESIGN AND ANALYSIS ISSUES IN ALCOHOL TREATMENT

State of Knowledge (Robert L. Stout, Ph.D.)

There have been many developments in treatment research methods over recent years. The development of new therapies, often combining multiple components, has triggered a need for complex, ambitious studies. At the same time, there have been methodological developments in several areas that in principle should allow studies to be conducted more effectively and result in more accurate conclusions.

Research design and implementation: The most important issue in research design is the problem of replicability. Findings of "efficacy" do not always translate into improved performance in non-research settings ("effectiveness"), and Project MATCH found that the effects of well-controlled treatments can vary substantially from site to site. Determining the conditions under which replicability can, and cannot, be expected should be a high priority for the Institute. Since treatment research studies tend to be complex, multivariate enterprises, there is also a need for methodological research on: (1) methods for bias minimization [e.g., improved urn randomization]; (2) improved power analysis tools; (3) treatment process measurement; (4) longitudinal research design; and (5) outcome and utility estimation. There is also a need for debate on the tradeoffs between investigators' needs for data and the burden on research participants.

Analysis of Treatment Data: There is a major need to bring already-developed statistical methods into wider use in treatment research. These methods can help to solve a number of problems of relevance to treatment researchers. The Institute should explore funding mechanisms to encourage quantitative scholars to work on alcohol treatment research problems. Furthermore, conference grants or other mechanisms could be used to facilitate the application of methods such as latent growth, structural equation models, event history models, zero-inflated Poisson methods, and Generalized Estimating Equations techniques. There needs to be support for methodological research on improved methods for missing data (especially in longitudinal analyses), and better methods for multiple event analysis, applications of decision theory, and advanced quantitative modeling or simulation.

Specific recommendations:

- There should be K awards designated for quantitative researchers interested in entering alcohol treatment research. NIAAA should also sponsor conference grants to disseminate statistical methods to treatment researchers.

- It is important to delineate reasons for lack of replicability of treatment effects across sites/studies. This research should be targeted at site by treatment interactions (large variations in the effectiveness of nominally similar treatments from one site to another) and reasons for loss of effectiveness when treatments proven efficacious in research settings fail to be effective in standard clinical settings.

ASSESSMENT IN ALCOHOLISM TREATMENT

State of Knowledge (John P. Allen, Ph.D.)

Accurate and comprehensive assessment is fundamental to both treatment of and research on alcohol problems. Practitioners are primarily concerned with the clinical utility of the assessment, particularly how well it identifies the needs of a given patient and guides treatment planning. Researchers are more likely to be interested in a broader range of variables that may quantify and explain the overall impact of an intervention and may not be directly related to clinical care (Connors et al., 1994). Researchers seem to place a much higher premium on formal assessment than do many practicing clinicians, who appear to rely more heavily on interviews, review of past records, or clinical impression (Nirenberg and Maisto, 1990). Validity and availability of relevant norms for a particular assessment instrument are of considerable interest to the clinician. The clinician is also concerned about ease of administration, scoring, and interpretation of the instrument as well as cost, time, and acceptability of the measure to patients (Allen et al., 1992).

A number of characteristics have to be considered when selecting an assessment instrument.

- Purpose and clinical utility - instruments can vary according to the sequential process of assessment, i.e., screening, diagnosis, triage, treatment planning.

- Assessment timeframe - current or lifetime.

- Age or target populations - e.g., adolescents, adults, older adults, pregnant women.

- Norms available - allows test performance to be compared with that of a large, relevant group of individuals; few alcohol-related instruments have ethnicity-based norms.

- Administrative options - e.g., written, interview, computer.

- Training for administration

- Established reliability and validity

Specific recommendations:

- Development of computerized adaptive testing algorithms, capitalizing on advances in decision tree technology.

- Construction of subpopulation norms for individual assessment instruments.

CLINICAL FACTORS IN THE TREATMENT OF ALCOHOL

AND DRUG PROBLEMS

State of Knowledge (Lisa M. Najavits, Ph.D.)

Most alcohol and drug abuse treatment programs (97 - 99%) provide some form of psychotherapy or counseling, and yet the clinicians that deliver this treatment have been little studied. Substance use disorders (including alcoholism) are the only disorders in which a major psychosocial intervention, aside from psychotherapy, i.e., Alcoholics Anonymous or other non-professional self-help group, remains the dominant treatment (Najavits and Weiss, 1994).

One of the most important findings from research is that clinicians are a key factor influencing alcoholism treatment outcome and retention (how long patients stay in treatment), typically accounting for more variance in outcome than do differences between active treatments or patient baseline characteristics (Najavits and Weiss, 1994). Clinicians' professional background characteristics, such as years of experience, training, etc., do not predict their effectiveness (Najavits and Weiss, 1994). Similarly, matching patients to clinicians produced null or mixed results (Sterling, 1998) as did the recovery status of the clinician (acknowledgment of substance use disorder) (McLellan et al., 1988). Effectiveness of individual clinicians becomes equivalent with adherence to a prescribed treatment approach according to some research (Crits-Christoph, 1991).

Topics of importance without clear conclusions include clinician personality characteristics and clinicians' beliefs about treatment of alcohol use disorders. The high rate of clinician burnout (Elman and Dowd, 1997) suggests the value of research into such topics as clinician-targeted interventions and clinician selection and training.

Specific recommendations:

- Promote research on clinicians' differences in effectiveness with alcoholic patients.

- Promote research on identification of variables that explain clinicians' differences in effectiveness with alcoholic patients.

Back to Top

TYPES OF TREATMENT

BRIEF INTERVENTIONS AND THE TREATMENT

OF ALCOHOL USE DISORDERS

State of Knowledge (Michael Fleming, M.D., M.P.H.)

The goal of brief intervention and brief counseling is to help people reduce or stop their alcohol use. While abstinence may be a long-term goal, the primary goal of brief interventions is to reduce alcohol consumption to low-risk levels and patterns of use. Brief intervention counseling can decrease alcohol use for at least one year in non-dependent drinkers in primary care clinics, managed care settings, hospitals, and research settings (Wilk et al., 1997), with similar effect sizes for men and women (WHO, 1996) and for all age groups over 18, including older adults (Fleming et al., 1997).

Brief intervention can reduce health care utilization as measured by reductions in emergency room visits and hospital days (Fleming et al., 1997), reductions in hospital readmissions (Gentilello et al., 1999), and reductions in physician office visits (Israel et al., 1996). Brief interventions may reduce mortality and health care and societal costs (Fleming et al., 1999) and can also result in improved clinical laboratory tests (Israel et al., 1996) and drinking and driving (Monti et al., 1999).

Specific recommendations:

- Conduct large multisite treatment trials that follow patients for at least five years (preferably 10 years) in order to assess morbidity (e.g., accidents, medical complications), mortality, and costs.

- Increase the number of effectiveness studies, e.g., how do we implement screening, assessment, brief counseling, pharmacotherapy, and referrals to therapists in the U.S. health care system.

BEHAVIORAL TREATMENTS

State of Knowledge (Ronald M. Kadden, Ph.D.)

This review of clinical research on behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches to the treatment of alcoholism covers cue exposure, contingency management, community reinforcement, coping skills training, relapse prevention, and patient-treatment matching. It identifies a number of gaps in knowledge and consequent research opportunities, which are summarized here. In the area of cue exposure research, there is need to identify the most potent cues, factors that moderate cue reactivity, and effective strategies to reduce the impact of drinking cues. Regarding contingency management methodology, encouragement should be provided to increase the application of this technique to alcoholism treatment, as well as to determine the most effective schedules of reinforcement and maintenance factors that would support sobriety after imposed contingencies are discontinued. With respect to the community reinforcement approach, the most effective elements of the intervention should be identified as well as means of sustaining their effects beyond completion of treatment. In the area of coping skills training, studies are needed to assess the relative effectiveness of its various components, and to foster the use both of functional analysis to guide the selection of targets for behavior change and of mastery criteria to assess the adequacy of skills training that is provided. In addition, further work is needed to substantiate the mediating role assigned to coping skills in the cognitive-behavioral conceptualization of recovery. With respect to the relapse prevention approach, further studies are needed to improve the system for classifying relapse episodes and to identify the most effective interventions for each type of episode. With respect to patient-treatment matching, despite a recent setback in research on this approach, it may nevertheless be the most effective way to identify which clients are most likely to benefit from each of the above treatment strategies. Initial steps in this direction would be to replicate the matching strategies that have the strongest support and to determine the minimum levels of client severity that are necessary for matching to be effective. Finally, there is considerable overlap among the various treatment approaches reviewed here and it is likely that further research along the lines suggested will impact several of them. This may lead to efforts to consolidate their most effective elements into a common treatment package.

Specific recommendations:

- Investigate ways to better maintain treatment effects (e.g., booster sessions, contingency management, role of environmental factors).

- Identify critical elements of behavioral treatments.

NONBEHAVIORAL PSYCHOTHERAPY

State of Knowledge (Carlo C. DiClemente, Ph.D.)

In the past 15 to 20 years, there has been a resurgence of interest in psychotherapies and psychosocial treatments that are not behavioral in nature.

There are few controlled clinical trials of psychodynamic treatments compared with either no-treatment controls or alternative alcoholism treatments, with the majority of outcome studies conducted in the late 1960s and 1970s. In general, there is little support for the utility of psychodynamically oriented treatments for alcohol abuse or dependence (Roth and Fonagy, 1996)

Interpersonal psychotherapy encourages participants to explore interpersonal relationships and problems through self-reflection, expression of emotions, and examination of current interactions within the treatment context; this treatment is most often delivered in a group therapy setting. Although controlled research does not support a unique role for this approach, there is some evidence that this type of treatment may be more effective for certain type of alcoholics (Litt et al., 1992).

The lack of controlled studies of cognitive techniques that are separate from cognitive behavioral techniques make it difficult to evaluate the unique effectiveness of cognitive therapy.

Motivational interventions are based on principles of motivational psychology, client-centered therapy, and the stages of change model and have provided a general and practical approach for changing behaviors associated with alcohol disorders. Responsibility for changing addictive behavior is assumed to lie within the patient, and ambivalence is recognized as a natural part of this change process. Studies over the past 10 years have demonstrated that motivational interventions are moderately successful in initiating change among a variety of individuals with alcohol-related problems (Miller et al., 1995). There are data to suggest that motivation and readiness to change are the best predictors of drinking outcomes throughout the posttreatment period for outpatients (PMRG, 1998). Motivational interventions appear to be particularly useful for individuals with higher levels of trait anger (PMRG, 1998).

Although there is a growing interest in alternative medicine approaches for the treatment of alcohol-related disorders, there are data available only for acupuncture. Overall, the findings of acupuncture treatment as an aid to rehabilitation and relapse prevention among alcohol dependent individuals are mixed suggesting that more controlled research should be conducted before this technique can be recommended.

Specific recommendations:

- Further examine motivation enhancement approaches in order to evaluate active ingredients (e.g., feedback, interpersonal style, length, setting, population) and how to best combine motivational interventions with other treatments with assumed different mechanisms of action and different targets of intervention.

- Encourage longitudinal studies of engagement in treatment and different paths of entry in order to evaluate the process of recovery across treatments and to better understand commonalties and differences in the paths and processes of recovery from alcoholism and associated problems.

Back to Top

INVOLVEMENT OF SUPPORT NETWORKS IN TREATMENT

State of Knowledge (Richard Longabaugh, Ed.D.)

Long-term studies have indicated that social factors are predictive of remittance and relapse in alcoholics and untreated problem drinkers (Humphreys et al., 1997). Moreover, managed-care alterations in treatment have reduced the importance of treatment factors in accounting for the variance evident in relapse (Humphreys, 1997). These observations suggest the importance of social network members in treatment.

Social networks may be conceptually divided into two subtypes, the pre-existing everyday social network in which the alcoholic may be embedded prior, during, and following treatment, and networks developed specifically for the purpose of facilitating the alcoholic's recovery, i.e., mutual self-help groups. Research on mutual self-help groups other than Alcoholics Anonymous is largely non-existent.

Most of what is known about involvement of the alcoholic's social network in treatment is limited to spouse and family involvement, with spouse involvement being much more prominent. Analyses across studies of the effectiveness of spouse and family involvement in treatment for alcoholism have demonstrated that their inclusion enhances treatment effectiveness (McCrady, 1989). This finding is somewhat mitigated by the observations that a significant number of alcoholics do not have spouses and a smaller percentage are without proximal families. Most martial therapy has been accomplished within the context of a cognitive behavioral conceptual model (McCrady and Epstein, 1995). The addition of behavioral marital therapy for alcohol abusers enhances the functioning of the couple, thereby enhancing outcome (Epstein and McCrady, 1998). Intervening with the spouse of an alcohol abuser who is unwilling to seek treatment has been shown to be highly beneficial (Miller et al., 1999).

When the focus moves from couple's therapy to family therapy, findings become more equivocal. Even less studied, is whether other members of the network outside of the family can be brought into treatment to enhance outcomes; an exploratory study by Longabaugh et al. (1995) suggests some beneficial effects. Early involvement by network supporters helps the alcoholic stay in treatment during the initial phase when they are likely to drop out (Galanter, 1993) and also helps to provide a long-term social context that is supportive of sobriety (Humphreys et al., 1997). Outside of couples and family therapy efforts, no studies have been identified that explicitly seek to accomplish the dual goals of support for reducing alcohol abuse and relationship enhancement within the broader social network.

Specific recommendations:

- Identify the conditions under which an intervention involving members of the network will be effective in short- and long-term in enhancing outcomes. These conditions include patient characteristics, network characteristics, and nature of the network intervention itself (with and without behavioral and pharmacological interventions), independently and in combination. This research should be theory-driven, and include testing the theory operationally.

- Emphasis should be placed on theoretically driven research that uses existing models of couples/family interventions for alcohol problems and tests whether the models can be extended to involve other members of the network, in lieu of the spouse/family member, and under what set of conditions.

NIAAA PORTFOLIO ON PSYCHOSOCIAL RESEARCH

(Cherry Lowman, Ph.D.)

The Treatment Research Branch addresses the primary problem of alcohol abuse and alcoholism through identification, development, and dissemination of effective treatment interventions. Three major types of intervention are developed or evaluated in treatment research supported by TRB: psychosocial interventions (for example, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy); pharmacological interventions (for example, naltrexone); and combined psychosocial-pharmacological intervention. This section of the Treatment Research Program Report presents information on psychosocial treatment interventions.

A number of advances have been made over the past decade in psychosocial treatment research on alcohol abuse and alcoholism. These include:

Continued development of the psychosocial research program. TRB has contributed to this program development by issuing Program Announcements and Requests for Applications, giving technical assistance, organizing workshops and symposia, and publishing monographs. For details on the portfolio, see the overview below.

Initiation in 1998 and intent to continue development of the Adolescent Treatment Research Program (see Category D below), a research grant program.

Initiation in 1989 and completion in 1997 of a cooperative agreement to conduct a multisite randomized clinical trial to assess the effectiveness of treatment-patient matching strategies for three types of psychosocial intervention(motivational enhancement treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy, and Alcoholics Anonymous facilitation therapy). P>Initiation of the Treatment Research Validation and Extension Program (TRVEP) in 1991, a program of contracts to assess the validity and reliability of widely used methodologies in alcohol treatment research (see discussions under Screening and under Relapse below).

Continued development of the treatment services research program (1990 - 1994), a research grant program with foci on treatment services and financing, treatment effectiveness, and primary care intervention studies; transferred to the newly formed Health Services Research Program in 1994.

Overview of FY 1999 Psychosocial Program

In FY 1999, the NIAAA Treatment Research Program funded 38 active extramural research project grants (30 R01s, 1 R37, 3 R29s, 2 R21s, 2 R03s), four Small Business Innovative Research (SBIR) grants (2 R43s, 2 R44s), five K awards (1 K01, 1 K02, 1 K05, 2 K23s), and four small contracts, making a total of 51 funded projects at a total cost of $13,160,228. These projects are described below under five general areas of psychosocial treatment research:

|

Topic |

Total Costs |

Description |

| (A) Controlled clinical trials |

$1,954,390 |

Pages 21 - 23 |

| (B) Relapse |

$1,970,639 |

Pages 23 - 29 |

|

(C) Family transmission and intervention |

$2,787,554 |

Pages 29 - 32 |

|

(D) Adolescent treatment |

$4,228,770 |

Pages 32 - 36 |

|

(E) Screening and brief intervention |

$2,218,875 |

Pages 36 - 39 |

Discussion under each of these headings provides background, brief descriptions of the projects, and results when available.

Back to Top

A. Controlled Clinical Trials

The keystone of alcoholism treatment research is the use of randomized controlled clinical trials to systematically assess the impact of behavioral, psychosocial and pharmacological interventions on behavioral outcomes. Such treatments are usually delivered in specialized medical or psychotherapeutic treatment settings, to patients who have self-referred or have been referred or recruited for treatment and who agree to participate in the study, by providers who have received professional training. The typical clinical trial employs a randomized controlled design in which treatment duration is 12 weeks and treatment outcomes at 12 months from the experimental condition are contrasted with 12-month outcomes from treatment as usual. They also provide an opportunity for extensive patient assessment along multiple concurrent dimensions postulated to predict outcomes.

Controlled Clinical Trials Funded in FY 1999

The 23 clinical trials discussed in the psychosocial section are of two types: research project grants independently initiated by the extramural research community (n=13) and research project grants submitted in response to a Request for Applications (n=10). Three clinical trials are discussed in this controlled clinical trials category; another two are discussed under "Relapse" (depression and social phobia); two under "Familial interventions"; 12 under "Adolescent treatment"; and four under "Screening and brief interventions."

Following are descriptions and findings, when available, of the research grants assigned to this category.

Alcoholics Anonymous. Dr. Kimberly Walitzer (AA11529) assesses the effectiveness of two strategies designed to facilitate involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous in the context of a 12-session outpatient alcoholism treatment program. Clients are assigned to one of three conditions: a minimal approach, a directive-confrontive approach, and a motivational approach.

Aftercare. Dr. James R. McCay (AA10341) compares outcomes over two years of follow-up from three types of aftercare intervention: (1) minimal aftercare (referral to self-help groups and brief telephone case management); (2) standard disease-model aftercare counseling (two group therapy sessions a week), or (3) one individual cognitive-behavioral relapse-prevention session and one group therapy session per week. Relative cost-effectiveness of the three different approaches will also be determined. Preliminary findings from this project, based on a partial sample, indicate that short-term outcome may be related to whether or not patients reside in structured abstinent living situations such as half-way houses or sober houses. Those who live in structured situations appear to enjoy better outcomes and may not require the most intensive intervention. Initial cost effectiveness evaluations suggest that costs of telephone case management such as locating subjects may be no less expensive than standard aftercare treatment. Confirmation of these findings requires comprehensive data analyses of the full study sample and all long term follow-ups.

Technology transfer. This project, under the direction of Dr. Jon Morgenstern (AA10268), represents the first systematic, controlled effort to transfer a treatment determined to be efficacious under experimental conditions to a real-world treatment practice. The two broad research questions addressed by the project are: (1) Can "front-line" treatment counselors be trained to deliver a standardized Cognitive Behavioral Coping Skills Treatment in real-world practice? and (2) Can research-based alcohol treatments achieve more effective outcomes than practice as usual in real-world settings? The project has successfully trained a cadre of counselors, using cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) manuals and professional trainers, and patients have been assigned to one of three treatment conditions: manualized CBT (high standardization), Real World CBT (low standardization), and traditional treatment. Two studies were completed during FY1999.

Study 1. Feasibility of knowledge transfer. The feasibility of training front-line counselors to deliver CBT using treatment manuals was examined in order to determine if this technology transfer strategy might aid in dissemination efforts. The sample comprised 29 substance abuse counselors drawn from two community-based treatment programs. CBT counselors reported high levels of satisfaction with the training, intention to use CBT interventions and confidence in their ability to do so. Supervisor and rater ratings indicated that 90% of counselors were judged as having attained at least adequate levels of CBT skillfulness. This study demonstrates the feasibility and promise of using psychotherapy technology tools - manuals, videotape monitoring, and supervision - as means of disseminating empirical knowledge to the substance abuse practice community. Results of this study have been submitted for publication.

Study 2.CBT treatment effectiveness as delivered by front line counselors. Preliminary analysis of within treatment outcomes of a randomized trial testing the effectiveness of CBT was conducted in a sample of 134 outpatients at 3 months follow-up. Participants were randomly assigned to three conditions: high standardization CBT, low standardization CBT, and a treatment-as-usual condition. In addition, the study took place in two settings: a) individual CBT therapy was added to intensive outpatient treatment as usual (n=90), and b) individual CBT therapy was offered as a stand-alone outpatient treatment (n=44). Using hierarchical linear modeling, neither treatment condition nor a condition-by-setting interaction was significant. Thus, participants appeared to experience equivalent good within-treatment outcomes across treatment conditions. Future analyses at 15-months follow-up may, of course, yield very different findings.

Computerized treatment interventions. Three Small Business Innovative Research (SBIR) Program grants are devoted to development of computerized treatment interventions which may be used as experimental or control conditions in future clinical trials and therefore have been included in this section. Two of the SBIR grants are in Phase I, development of the prototype.

Dr. Reid Hester (R43 AA11703) will develop and evaluate an interactive computer software program that provides a brief motivational intervention for individuals who range from at-risk drinkers to alcohol dependent individuals. The program will utilize the "FRAMES" elements common to effective brief motivational interventions.

The interactive voice response (IVR) telephone system is being utilized by James C. Mundt (AA12366) to develop a computerized aftercare IVR system for self-monitoring of daily drinking with automatic feedback mechanisms for posttreatment relapse intervention and prevention.

Dr. Emil Chiauzzi (AA11694) has developed a computerized program to be offered through substance abuse and alcohol treatment programs to prevent relapse in early recovery. Dr. Chiauzzi's approach utilizes an important new technology for teaching complex skills with computers. This project is in Phase II, field-testing.

Back to Top

B. Relapse

Despite the discomfort and danger of acute withdrawal from alcohol use, most alcoholics initially achieve a period of sobriety with or without formal treatment. Unfortunately, many return to drinking within a short period of time. Alcoholism has therefore come to be conceptualized as a chronic relapsing disorder similar to other chronic health conditions. Understanding the nature of relapse is fundamental to the identification and development of interventions that will contribute to positive long-term outcomes.

There are several types of studies that facilitate research on the addiction recovery process. These include both treatment outcome studies and natural history studies both of which assess the impact of multiple domains of variables (the hypothesized relapse predictors) on long-term outcomes. These also include studies that focus on elucidating or experimentally manipulating specific phenomena posited to influence long-term drinking outcomes such as psychiatric comorbidity, craving, and neurocognitive characteristics. Finally, secondary analyses of existing databases may enable testing of relapse hypotheses and modeling of recovery processes. Research project grants in TRB's psychosocial portfolio relevant to relapse prediction are discussed below under one of these six categories.

Relapse-Related Projects Funded in FY1999

Treatment Outcome Studies

Although most treatment research is concerned with treatment outcomes, the term in this context refers to clinical studies of long-term outcomes (usually 12 months or more) of patients treated in "real world" rather than experimental settings. Since it is difficult to study variability in a specific natural treatment process (the "black box"), the emphasis in studies of this type usually is on identification of patient characteristics that predict long-term behavioral change.

Replication and Extension Research. The three contracts (N01AA1006, N01AA1007, N01AA10011) under TRB's Treatment Research Validation and Extension Program (TRVEP), awarded to Brown University, the Research Institute on Addictions, and the University of New Mexico, were treatment outcome studies in TRVEP's first program of research, the Relapse Replication and Extension Program (RREP). The purpose of this study was threefold: to replicate and assess the predictive validity of Marlatt's taxonomy of relapse precipitants (i.e., high risk situations); to contrast alternative taxonomic conceptualizations such as those represented by the Inventory of Drinking Situations and the Reasons for Drinking Questionnaire; and to assess the predictive validity of other putative predictors of relapse in addition to Marlatt's taxonomy of high risk situations. The focus of the three treatment outcome studies was prediction of behavioral outcomes and posttreatment functioning from an array of domains hypothesized to predict relapse, including Marlatt's high risk situations, negative affect, testing personal control, coping behavior, outcome expectancies, self-efficacy, and craving.

The primary conclusions of this study were: (1) although the methodology utilized to collect data for the taxonomic method of relapse classification clearly serves several important clinical functions, predictive validity and cross-site reliability is insufficient to justify its use for scientific research in its present form; (2) the Reasons for Drinking questionnaire, which extends Marlatt's original method by replicating the questions in self-report Likert scale format, did appear in the one site tested to have moderate predictive validity; (3) both effectiveness of coping behavior and belief in the disease model of alcoholism were strong predictors of long term outcomes; (4) adverse events, stressors, self-efficacy and outcome expectancy did not predict most long-term outcomes examined in the RREP studies. These latter variables, however, may represent relatively transient conditions, ones proximal to relapse, that would not be consistently captured in the bimonthly assessments conducted in these studies. The results of this relapse research program, including theoretical and methodological articles pertinent to relapse research, were published in a December 1996 Supplement to the journal Addiction (Lowman et al.).

The three RREP contracts have been extended to complete integration of the three site-specific individual databases into a single multisite database in order to replicate the original analyses on a larger sample. In addition, the three sites will complete analyses of data on craving and treatment outcomes.

Meta-Analysis of Treatment Outcome Research (Finney, AA08689). This project extends a previously developed database to provide a meta-analytic review of outcome and effect size in alcoholism treatment research published in English between 1970 and 1998. With the data from this project, it will be possible to describe the nature of alcoholism treatment research over the 29-year period and the extent to which it reflects various components of methodological quality. It will also be possible to determine whether the methodological quality of alcoholism treatment research has improved over time.

Longitudinal Natural History Studies

These types of studies differ from treatment outcome studies in that they do not usually include a treatment component. Natural history studies examine over time the unfolding of the in vivo course of alcohol use and abuse in a specific population. Such studies make major contributions to knowledge of alcohol use disorders by illuminating etiological processes, familial transmission, mechanisms underlying post-treatment functioning, factors contributing to spontaneous recovery, and factors contributing to the emergence and remission of alcohol-related problems in specific populations. There are three natural history studies in TRB's psychosocial portfolio. Two are discussed here; Robert A. Zucker's longitudinal study of children of alcoholics is discussed in the section below on familial transmission.

Alcohol Use Among the Elderly. Dr. Rudolf H. Moos (AA06699) is conducting a longitudinal study on problem drinking and life stress among older adults. This project currently has three components: (1) a ten-year follow-up, now completed, of a community sample of late-life problem drinkers and non-problem drinkers and of spouses included in earlier follow-ups, now completed; (2) a 4 - 5 year follow-up of a nationwide sample of more than 5,000 treated late-life alcoholic patients; and (3) analysis of Medicare data to calculate readmission and mortality rates, and to identify predictors of readmission and mortality in late-life VA substance abuse patients. Results from the community study show that late-onset problem drinkers may be more reactive to health problems and people's reactions to their drinking than early-onset problem drinkers who may require more structured health care to successfully recover from alcohol problems. Older problem drinkers have relatively flexible coping styles, which suggests to the PI that their adaptation can be enhanced either by improving their social resources or by reducing their reliance on avoidance coping. "The findings suggest that the best treatments for alcohol use disorders are those that help patients manage their life circumstances, that low intensity treatment for longer intervals may be most helpful, that most alcoholic patients can be treated in outpatient settings, and that a supportive, well organized treatment regimen may be especially important for older patients." For a full report, see Chapter 15 In Gomberg, E.S., Hegedus, A.M. and Zucker, R.A. (Eds.), 1998, Alcohol Problems and Aging, pp. 261-279, NIAAA.

Recovery and Help-Seeking Processes in Problem Drinkers. Most problem drinkers do not seek help from professional treatments or Alcoholics Anonymous, yet many resolve their problems without it. In order to understand the natural resolution process and to develop interventions to reach problem drinkers who do not seek help, Dr. Jalie A. Tucker (AA08972) has designed a project to distinguish factors that influence help-seeking for alcohol problems from factors that influence problem resolution. Studies 1 and 2, completed in the first 5-year period, recruited problem drinkers from the community using media advertisements.

Study 1 involved a retrospective assessment of events during a 4-year period that surrounds the initiation of stable abstinence that had lasted 2 years or more. Across help-seeking groups, resolution was associated with decreases in negative events from the pre- through the post-resolution period and with increases in positive events during the first year of maintenance. Interventions, especially treatment, facilitated positive changes after resolution onset, but these help-seeking differences overlapped the more general pattern of events found to surround resolutions achieved through any one of several pathways. Tucker et al. (Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology, 3, 195-204, 1995) report a pilot version of Study 1.

Study 2, still under analysis, was a prospective follow-up of untreated problem drinkers who had recently initiated abstinence or moderation drinking and was guided by behavioral economic theory. In the second project period, two additional studies are being conducted. Studies 3 and 4 were initiated in the current five-year project period.

Study 3 is a prospective replication of Study 1 and involves a two-year follow-up of problem drinkers who recently initiated a resolution attempt with or without interventions.

Study 4 is a one-year follow-up of recently resolved, untreated problem drinkers and involves intensive study of the natural resolution process through daily participant self-monitoring by means of a computerized interactive telephone system. Studies 3 and 4 will yield detailed information about the dynamics of resolution and the role of contextual variables and interventions promoting it.

Psychiatric Comorbidity

Among persons with alcohol use disorders in the general population, lifetime prevalence for any psychiatric disorder may be as high as 44 percent. Most psychiatric disorders have been found to precede alcohol use disorders in onset, with the exception of mood disorders, which frequently appear to develop after onset of alcoholism. Research indicates that psychiatric comorbidity predicts poorer outcomes in alcoholic patients and has indicated that treatment for both disorders should improve outcomes for dually diagnosed patients. Treatment interventions, however, need to be tailored to the specific psychiatric condition. This is still an underdeveloped area of alcohol treatment research. There are only three independently initiated psychosocial research projects on this topic: one is a treatment outcome study and two are clinical trials.

Treatment Outcome Study: Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome (PTSD). Following are preliminary findings from Dr. Pamela J. Brown's R29 research project (AA10011) to study PTSD in a clinical sample of substance abuse patients: (1) PTSD and traumatic events are common in substance abuse patients (94% had experienced an average of 3.5 traumatic events in their lifetime and over half met diagnostic criteria for PTSD); (2) PTSD patients relapsed more quickly than non-PTSD patients (at 35 versus 69 days, respectively); (3) improved PTSD was associated with better substance use disorder (SUD) outcomes but sustained remission from SUDs was not associated with improved PTSD; (4) daily drinking records indicate that PTSD patients tend to have a more volatile substance use course, cycling frequently between "illness" and "wellness" states; (5) for female patients, number of PTSD re-experiencing symptoms is a significant predictor of substance use outcomes, but no baseline measure of substance use predicts PTSD outcomes (Brown, P.J & R.L. Stout, Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, in press); and (6) PTSD patients had a greater number of hospital overnights for addiction treatment compared to non-PTSD patients (Brown, P.J., Stout, R.L. & Mueller, T., 1999, Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 13, 115-122.).

Clinical Trials: Depression. This clinical trial (R.A. Brown, AA10958) tests the hypothesis that addition of cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) for depressive symptoms will improve treatment outcomes among comorbid alcoholics in a standard, partial-hospital alcohol treatment program. The control condition for the CBT-depression condition is adjunctive relaxation training.

Clinical Trials: Social phobia. In this project (Randall, AA09751), the objective is to determine whether or not concurrent treatment of psychiatric co-morbidity leads to improved treatment outcomes for alcoholics. In the experimental condition, a subgroup of alcoholic outpatients who suffer from social phobia receive concurrent manualized cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) for their alcoholism and for their social phobia. In the comparison group, only the alcoholism is treated with CBT. All data have been collected (baseline, 3, 6, 9, 12 months) for 110 outpatients with alcoholism and social phobia, 72 of whom are men, 38 of whom are women. The database has been prepared for analysis and findings will be available in 2000.

Neurocognitive Predictors

More than half of patients entering treatment for substance use disorders evidence mild to severe neuropsychological impairment (e.g., in executive control, memory, new learning, and visual/perceptive skills). It has been assumed that neuropsychological impairments such as these would be responsible for poor treatment outcomes either by leading providers to interpret impaired individuals' dysfunction as noncompliance behavior or by the limited ability of impaired patients to acquire and integrate new information with previous learning, or to plan and maintain behavioral alternatives to substance use.

Impaired Executive Function and Treatment Outcomes. Contrary to these expectations, Drs. Jon Morgenstern and Marsh E. Bates, in a recently completed study partially funded by TRB grants (AA10268 and AA11594, respectively), found that impaired executive function had no direct effect on treatment outcome among patients admitted to two 12-step treatment programs. The authors did find, however, that impairment significantly moderates the relationship between intermediate change processes and outcome. Change processes considered therapeutically positive (e.g., increasing self-efficacy, maintaining high levels of motivation to abstain and facilitating connection to AA) were strongly related to treatment outcomes in unimpaired individuals but were only weakly related in impaired individuals. These findings suggest to the authors that (1) outcomes for unimpaired and impaired patients may be mediated by different factors that sustain two different pathways to the same outcome; impaired patients may have reduced risk of relapse through an as yet unidentified protective factor; and (2) "inclusion of cognitively impaired individuals in substance use clinical trials might obscure treatment effects because processes targeted by treatments do not appear to operate in the same fashion for impaired and unimpaired individuals..." (Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Volume 60, 1999).

Alcohol, Aging, and Dementia: Neuropsychological Effects (Saxton, R29 AA10981). This project is a five-year cross-sectional and prospective study to validate the taxonomy of Alcohol Dementia, delineate cognitive profiles associated with the disorder, differentiate the disorder from Alzheimer's disease, and to investigate the validity, specificity, etiology and natural history of the taxonomic category of Alcoholic Dementia and the long term implication of abstinence on the disease process.

Craving

Although craving, as currently measured, has failed as a consistent and strong predictor of relapse in psychosocial research, interest in the construct has survived in clinical as well as basic science circles and has recently been revived with the advent of research in medications development (Monti et al., in press). There are two recently funded projects in the TRB psychosocial portfolio that examines, in controlled laboratory experiments, mediators of cue reactivity.

Information-Processing Theory. Dr. Tibor Palfai in anR29 project (AA11534) utilizes information-processing theory as the framework for research design. The project investigates, through an experimental laboratory study, the effects of cognitive urge control strategies (i.e., Distraction, Suppression, Acceptance, or no instruction) on subsequent processing of alcohol-related information such as anticipatory responses to alcohol cues. In addition to this primary objective, the project will examine mechanisms by which efforts to control urges to drink may increase subsequent reactivity to cues. A third objective is to examine conditions under which specific urge coping strategies are most effective.

Extinction Performance. Dr. Paul R. Stasiewicz (AA12033) will conduct an initial test in a human clinical sample of an animal model of extinction performance. Specifically, the project will examine the effect of context on measures of craving and alcohol cue reactivity in treatment-seeking alcoholics. The first four of six groups will be compared to test if post-extinction context affects renewal of reactivity to alcohol beverage cues. Group 5 will be utilized to test whether or not the presence of an extinction cue (i.e., one that was paired with the extinction context) can reduce craving and alcohol cue reactivity during the post-test. Group 6 will examine whether or not a procedure designed to increase saliency of the extinction cue can further enhance this effect.

Secondary Analyses

Relapse onset and its prevention have been the major focus of relapse interventions whereas antecedents of relapse termination and mechanisms of abstinence maintenance, although they may contribute equally important insights to treatment research, have been largely neglected.

Relapse Onset, Relapse Termination and Abstinence Maintenance. Dr. William H. Zywiak, in an exploratory study (R21 AA12302), will utilize the Project MATCH database to conduct secondary analyses on these three aspects of the recovery process. A primary aim of the project will be to determine the interrelationships of relapse onset, relapse termination and abstinence maintenance characteristics and the relationships of these three domains to temporal and alcohol-related parameters of relapse and general treatment outcomes.

Back to Top

C. Familial Transmission and Intervention

Family studies in TRB's psychosocial portfolio focus on families in which at least one member is alcoholic, usually a spouse or parent as in the projects discussed below. Families affected by alcoholism are as heterogeneous as alcoholics are in general and the risks to spouses and children of alcoholics will vary with the substance use status of the alcoholic (remission or relapse), density of family history of substance abuse, and psychiatric comorbidity of substance abusing or other family members. Some alcoholic families may be buffered from the negative effects of alcoholism by social environments and cultural attitudes and rituals that serve as protective factors. There are three types of family studies in the TRB portfolio: (1) transmission studies to examine factors that influence recurrence of alcohol/drug problems and associated comorbidities (for example, conduct disorder and depression) within families across generations, (2) a clinical trial that assesses the effectiveness of couples therapy on alcoholics' treatment outcomes and on marital quality, and (3) a treatment outcome study.

Familial Transmission and Intervention Projects Funded in FY 1999

Transmission Studies

There are five transmission studies in the TRB portfolio: three natural history, youth and development studies and two studies that conduct secondary analyses of major twin databases.

Natural History Studies: Alcoholic Families and their Children

Risk and Coping in Children of Alcoholics (Zucker, AA07065). This project is a longitudinal developmental study of children of alcoholics from the age of three years on and of characteristics of their parents. Both alcoholic and control families were recruited from a community sample of homes in which the father was alcoholic at baseline. By the time these children mature and the data are analyzed, there should be findings of major significance on the etiology of alcoholism and the familial mechanisms that underlie its emergence. Study findings are likely to suggest new strategies for early preventive intervention. Even now, as the children enter early adolescence, the project has demonstrated that the already known markers of adolescence and later life that presage greater prevalence of alcohol use disorders are showing up first in the highest risk families. Thus, 82 percent of the 9 to 11 year old boys who have had their first alcoholic drink and 75 percent of 12-14 year old boys (based on a partial sample) who are already drinking and have had their first drunkenness experience are children of alcoholics. These differences in early drinking experience of children in alcoholic homes parallel earlier study findings that by ages 3 to 5, children of alcoholics were better at identifying and labeling alcoholic beverages (that is, they already had a better idea of what this substance is, as a drug).

The study continues to document that behavioral markers of later adverse outcomes, and possibly also of higher risk for alcohol use disorder, are not uniformly distributed among children of alcoholic parents. Although the strong association of alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder in adulthood has been known for some time, the manner in which this has impact on family functioning, and even the way in which this set of adult characteristics can serve as an indicator of family risk has been less well understood. This project has found evidence that families with antisocial fathers have more children who manifest behavioral disturbance of both mood and aggressiveness/undercontrol, even at ages 3 to 8, than do other COAs in the sample.

At this point it is not possible to determine how much the observed parallelism between life damage in the antisocial alcoholic parents and poor behavioral outcome in the children is regulated by genetic factors, environmental factors, or some combination of the two, or more importantly, to identify what the specific gene-environment interactions are that are involved in these transactions. A small offshoot study from the project has indicated that serotonergic system differences may regulate some of these effects; a peripheral measure of this system, whole blood serotonin, was lower in the children of alcoholics who were higher in problem behavior. Other recent work has shown that the family rearing structure is different in the high risk, antisocial alcoholic families, and the emergence of risky externalizing behavior develops at a different rate in these family environments than it does in the lower risk families. Plans continue to call for the examination of a number of interactive and mediation hypotheses as the long-term study continues.

Biological Risk Factors in Relatives of Alcoholic Women (Hill, AA08082). This is a five-year developmental study of a cohort of high-risk male and female children of women with a severe form of alcoholism (i.e., early age of onset and high familial density). The objectives of the study are to model (1) age of onset for regular drinking and (2) severity of psychopathology in the high-risk cohort as compared with a control group of low-risk offspring. This research has already demonstrated that reduction in P300 occurs in offspring of alcoholic women as it does in children of alcoholic men and affects girls as well as boys. The investigators also found that psychopathology among the children of these alcoholic women was five to six times higher than control children and tended to increase as they matured but this trend was not apparent when the custodial father was not alcoholic.

Familial Transmission of Alcohol and Related Problems (Johnson, AA11699). In a longitudinal study of adolescents, followed from ages 12 to 31, a broad range of variables and 13 years of data are utilized to study the relationship of developmental outcomes to characteristics of alcoholic families as compared with nonalcoholic controls. The PI will: examine the predictive value of subtyping alcoholic families (based on timing and onset of alcoholism in parents); assess developmental outcomes of familial risk (based on psychiatric comorbidity and transgenerational drinking histories, including those of grandparents) as compared with risk-free families; and will evaluate within group variations in resilience and vulnerability among 25-31 year olds as influenced by the relationship between drinking outcomes and potential mediating and moderating variables.

Twin Studies

Genetics of Alcoholism and Depression (Bierut, AA00231). This project, funded by a K23 award, utilizes secondary analyses of Australian twin and COGA databases to examine the genetics of alcoholism and depression. In completed analyses of Andrew Heath's Australian twin study, Dr. Bierut found that shared genetic effects more fully explained familial aggregation of depression for both men and women than did a shared family environment. Her COGA analyses will focus on the genetic overlap between alcoholism and habitual smoking. In addition, the PI is recruiting subjects for a prospective study to further elucidate the relationship between alcohol dependence and major depressive disorder in a sample of siblings of alcoholics.

Familial transmission of Antisociality and Alcoholism (Slutske, AA00264). Funded by a K01 award, this project analyzes three twin databases (Andrew Heath's Australian database, the Vietnam Era Twin Registry, and the Dutch twin registry) with a focus on identification of mechanisms responsible for familial transmission of antisociality and alcoholism. In addition, Dr. Slutske is collaborating with Australian survey researchers to recruit an additional generation to Heath's twin database, the young adult offspring (1964-1976) of previously interviewed Australian twins and spouses. The enhanced database will have a total of 873 parents and 1,913 offspring.

Treatment Intervention Studies

There are three family/significant other intervention studies.

Alcoholic Couples -- Two Models of Heterogeneity (McCrady, AA07070). This project is a randomized controlled clinical trial that assesses in a clinical sample of alcoholic women the efficacy of alcohol-related Behavioral Couples Therapy with Relapse Prevention, adapted for women, as compared to an individually-oriented women's treatment. A secondary aim of this project is to assess the contribution to treatment outcome of individual psychopathology, partner psychopathology, quality of the intimate relationship, and functioning of other parts of the woman's social network.

Domestic Violence among Male Alcoholics in Treatment (O'Farrell, AA10796). This treatment outcome study has as its primary objective replication and extension of earlier research on the impact of Behavioral Marital Therapy for alcoholic men and their wives on domestic violence. This extension will determine whether or not standard individual alcoholism treatment for alcoholic men will have comparable effects among remitted alcoholics; that is, domestic violence will return to the low levels characteristic of nonalcoholic couples. Dr. O'Farrell will further explore these subjects through analyses conducted under a K02 award (AA00234).

Intervention with Significant Others (Miller, AA09774). The long-term objective of this study is to develop effective methods for counseling concerned significant others (CSO's) that will improve outcomes for them and for the problem drinkers about whom they are concerned. Toward this objective, three alternative strategies for counseling CSO's are being compared in a randomized trial: (a) Alanon-oriented approach, (b) Johnson Institute intervention, and (c) community reinforcement approach (CRA). The results of this trial have been striking. CSOs who received the community reinforcement and family training intervention succeeded, in 67% of cases, in engaging their identified patient (IP) in treatment. CSOs assigned at random to the Al-Anon facilitation condition engaged their problem drinker in treatment in only 13% of cases, and for the Johnson Institute intervention condition the comparable figure was 23%. In all three conditions, CSOs at 3-month follow-up showed significant improvements in psychosocial and emotional functioning. This is one of the scientific activities funded by Dr. Miller's K05 award (AA00133).

Back to Top

D. Adolescent Treatment

Alcohol is often abused by adolescents with consumption and risk for alcohol-related consequences increasing with each grade in school. By the 12th grade, as many as one-third of high school students have reported intoxication at least once during the past 30 days. National high school survey data (grades 8-12) show that some indicators of excessive drinking have increased over recent years (e.g., the prevalence of heavy drinking--five or more drinks during the past two weeks). Consequences of adolescent alcohol abuse may include: fatal injuries such as traffic deaths, suicides, homicides; impaired social and academic functioning; psychiatric problems such as antisocial, mood, and anxiety disorders; and high-risk problem behaviors such as polydrug use and the serious risks for increased problem behaviors and morbidity that it entails.